Reviews

The Story of Early Roger Dubuis

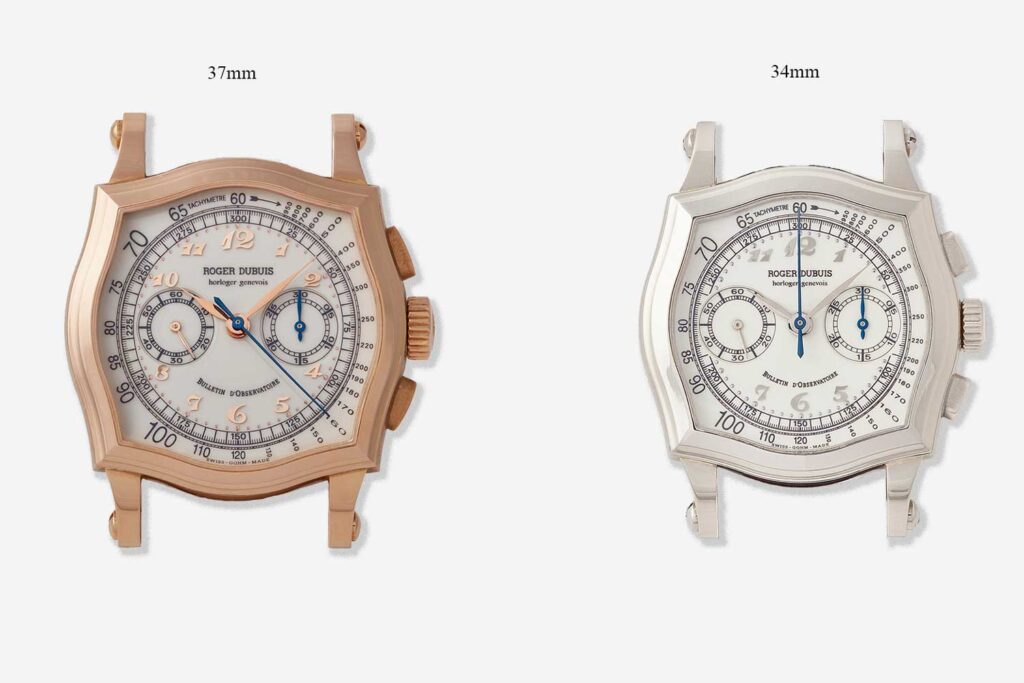

The Hommage was made in three different sizes: the 34mm H34, the 37mm H37 and the 40mm H40. The H34 and H37 took considerable inspiration from the Sector of Scientific dial Patek Reference 130s. You can turn to page 66 to see how closely the Roger Dubuis watches resemble these. But it is the reference H40 that I consider to be Roger Dubuis’ true master work of design. Because it is specifically in the 40 mm H40 reference that you find Roger Dubuis’ Breguet numeral dials which are possibly the most beautiful modern chronograph dials in recent memory.

Says Auro Montanari aka John Goldberger author of Patek Philippe Steel Watches, “For modern chronograph design the Roger Dubuis with Breguet numerals is one of the best.” These dials are strongly inspired by the highly coveted Breguet numerals dials found in the reference 130 and 1463. Says Montanari, “Sure the inspiration is clear. But Dubuis didn’t just copy them he elevated the design language of the dials with beautiful touches such as applied dots for the minutes.” Also unique is Dubuis combination of applied Breguet 12, 5, 6 and 7 indexes with thick applied pointed stick indexes. Says Montanari, ‘Also look at the fonts that he chose for the tachymeter and the subdials, the twisting guilloché and other patterns as well as the highly stylised leaf hands; everything had a slightly more Latin, expressive charm but very importantly without being Baroque.”

Close up of the applied Breguet numerals on Wei Koh’s H40 (Image: Tom Chng).

For me A Collected Man has become the place to source one of these amazing watches and I would also like to applaud them for the wonderful work in documenting the history of these wonderful timepieces. So without further ado let’s get into this story!

Roger Dubuis, From Watchmaker To Brand

Roger Dubuis was, first and foremost, a watchmaker. Having spent nine years at Longines starting in the late 1950s, he worked in the after-sales department where he repaired and cared for their deeply respected chronographs.

Then moving on to Patek Philippe where he stayed for the best part of two decades, working alongside the likes of Svend Andersen in the complications department. Constructing the maison’s finest and most complex watch movements, specialising in the construction of gongs, minute repeaters and perpetual calendars. Building a reputation as one of the finest watchmakers in Geneva, if not the world.

Roger spent a large part of his career at Patek Philippe. This would create a fundamental impression on him and his work in later years.

Dubuis developed this module with Jean-Marc Wiederrecht (founder of retrospective complication specialist Agenhor) for Harry Winston, who would later announce their own version of a biretrograde perpetual calendar at Baselworld in 1989. This was the first time the world had seen this complication in a wristwatch, one which Patek Philippe themselves, the master of complicated watchmaking at the time, had never put on the wrist. Perhaps Dubuis was now properly showing what he could do, intentionally attempting to one up the historic watch house. The parallels with other notable independent watchmakers, who started their careers in restoration then complex movement design, is not lost on us. A notable example is of course François-Paul Journe, who worked as a freelance movement designer before setting up his own manufacture.

One of Roger Dubuis’ first technical achievements was the creation of the world’s first bi-retrograde perpetual calendar in collaboration with Jean-Marc Wiederrecht in 1989.

A Roger Dubuis Bi-Retrograde Calendar Chronograph (ref. H40 560) from the 2000s.

First producing two lines, the Hommage and Sympathie series, each housing Roger Dubuis’ in-house calibres with time only, chronograph and perpetual calendars on display. It’s these early models that we’re choosing to focus on in this article, as they have garnered most interest from the collecting community to date. In particular, his two-register chronographs have become highly sought after in recent times. We also believe that they truly demonstrate Dubuis’ style and masterful technique to the full, as some of early pieces would have been built and regulated by the man himself.

Based on the legendary Lemania 2310, the Roger Dubuis chronograph calibres built on a very strong foundation, as this is the ébauche famously used in many notable Patek Philippe calibres of the past. Integrating this ébauche and finishing their movements to an impressive level of finesse and accuracy, every piece produced earned the Poinçon de Genève, or the Geneva Seal, as well as being certified by the Besançon Observatory. Something that only Patek Philippe was achieving at the time. We will go into more detail on both of these certifications below.

We spoke with a cross section of people who knew Roger Dubuis prior to his death in 2017, whether it was while he was working at Patek Philippe or from when they ordered some of his early models from him at SIHH as a retailer. Crucially, they all agreed on how humble, knowledgeable and fastidious the man was, with an utmost respect for his work and how he approached watch making.

A man whose respect for Roger Dubuis predates the brand is our recent interviewee, Dr Helmut Crott, who knew Dubuis while he was at Patek Philippe and sympathises with him when it came to running a watch brand after his own experiences with Urban Jürgensen. “I knew it was a hard job, but when they started it in 1995 that was really the best time to be starting a new brand in my opinion.” And Dr Crott was right, as the brand grew to an impressive size in the matter of a decade.

It’s hard to tell whether the young brand was extremely popular when it started or just disorganised, as when Mikael Wallhagen, now Head of the Watch Department at Sotheby’s in Geneva, placed an order with Roger Dubuis at SIHH in 1998 for 25 watches that never appeared. “Six months later we were back in the shop in Sweden and hadn’t seen any watches arrive. We chased them up and they said they didn’t have our watches as they can’t make enough. We never did get them in the end.”

And getting hold of them now can be just as tricky, “In the three years I’ve been at Sotheby’s I don’t think we’ve had one come through our doors. They are mainly changing hands privately as there are just so few on the market.” Wallhagen even has friends wanting to buy his Hommage Chronograph right off his wrist, not to mention all of the collectors and dealers who see him wearing it at auctions and make him an offer right there on the spot. There is a good reason why there are so few on the market, because so few were made. It is said that Dubuis originally only wanted to make 26 of each variant but Carlos Dias stepped in and demanded that 28 were made, as that would market a lot better in the Asian arena. Although it is also possible that they produced 28 as it was a variation on 208, Dubuis’ resignation number from the École d’Horlogerie de Genève.

So, the most you will ever be able to find of one type of early Roger Dubuis is just 28, although there are a few that were made as unique pieces as well. As Wallhagen found out when he took an early Roger Dubuis he’d bought from a dealer in New York to the manufacture and showed it to Dubuis himself, who remembered the model exactly and told him they made it in four different dials and four different cases but there was only one example of each.

That wasn’t the only time that Dubuis’ vast and extensive knowledge of his work has been proven, as Dr Helmut Crott told us about the time he bought what he thought was a rare Patek Philippe in America, but having no idea what he exactly had. This was before the days of readily accessible source material and biographies on the manufacture. So, he took it to Dubuis while he was still working at Patek Philippe, who announced “Helmut, I remember very well that we only made three of these.” This was about a decade after the watches left the manufacture.

From having a “hole in the wall” stand at SIHH in 1998, as Wallhagen described it, to employing over 450 people generating about CHF100M of revenue a year. The brand’s expansion has been astronomical since their early days and limited production runs. But it seems that these low numbers are now spurring on the second-hand market. Jason Singer, a well-renowned collector of early bubblebacks, important Patek Philippe’s and now early Roger Dubuis echoes this sentiment, “I look for them every day online but they’re becoming really tricky to find. I often miss out on them by a couple of hours, if that.”

However, while there is no lack of demand for these watches in the market, we feel like there is little reliable and trustworthy information out there on these early Roger Dubuis models. As such, we have pooled all of our resources from our experience handling Roger Dubuis pieces and information from credible sellers such as auction houses to create this reference point for some of the most sought-after early Roger Dubuis pieces.

The Hommage Chronograph

Roger Dubuis launched in 1995 with orders from retailers being placed quickly after that. This palladium chronograph is the earliest example we could find, with paperwork stamped 22nd November 1996. Another example we had passed through our hands was stamped 11 December 1996, coming to us directly from the retailer who kept this piece aside from the very first order they placed with the brand. These early, often untouched, examples offer a unique insight into what Dubuis wanted to do with these watches. In fact, when you sit one next to a Patek Philippe 130, the design codes that the Hommage inherits are obvious.

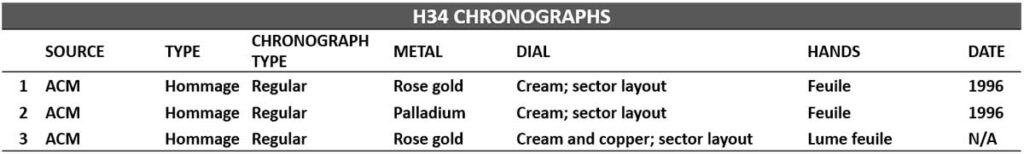

H34 came in three configurations, two with Sector dials and applied Arabic indexes and one version with a Sector dial and painted luminous Arabic numerals and hands.

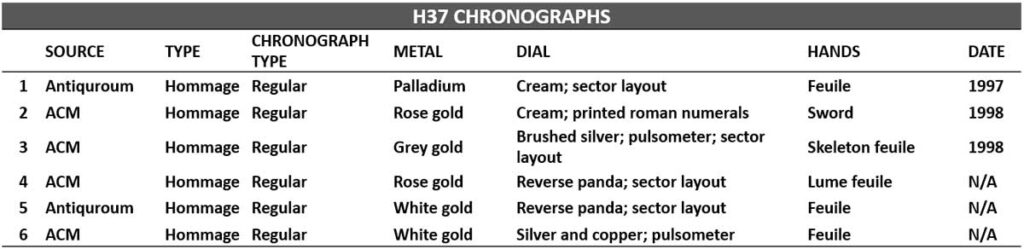

H37 came in six versions, three with Sector dials with Applied Arabic indexes, with printed Roman Numerals and two with luminous Arabic indexes.

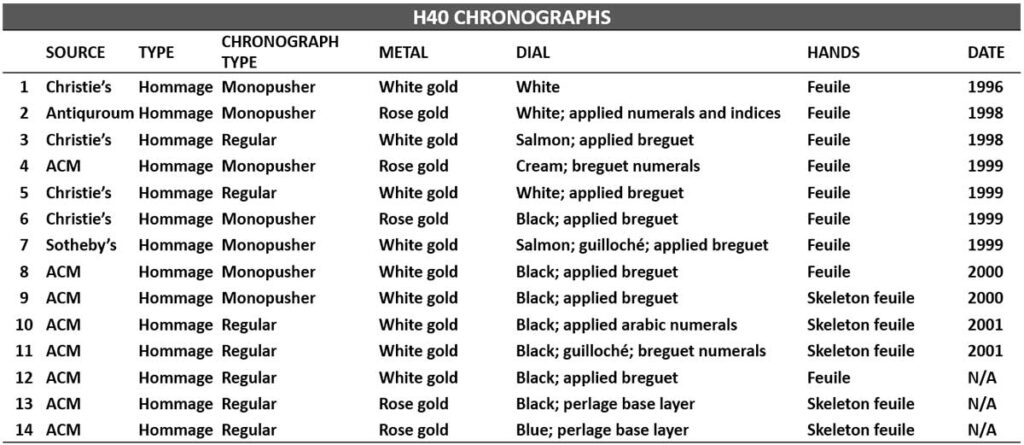

H40 came in 14 dial versions, nine with applied Breguet indexes and five with applied Arabic indexes. None of these were sector dials. This dial would eventually become a playground for colour and dial decorations and represent some of the most inventive dials in modern watchmaking.

As we already know, Dubuis learned the fine arts of watchmaking at Patek Philippe and on starting his own brand he intended to pay tribute to the craft and in particular the Genève style so often associated with historic manufacture. That’s why these Hommage chronographs came with so many dial variations, using guilloché, applied Breguet numerals and lacquer to great effect. Part of the allure of collecting these watches is in discovering new dial variations, with everything from salmon dials to Pulsometer chronograph scales out there for those who look hard enough.

The H34 and H37 came with Sectors or Scientific Dials clearly influenced by the Patek reference 130. There is only one H37 reference from 1998 that does not use a Sector dial and has Roman numerals and sword hands.

Collector and founder of the Singapore Watch Club Tom Chng, owns this beautiful and rare version of the H34 with Sector dial and painted luminous Arabic numerals and hands

The rose gold H40 with Arabic numerals, skeleton feuille hands and an ultramarine blue lacquer dial with perlage pattern belonging to collector David Lim.

Michael Tay’s white gold H40 with Breguet numerals, skeleton feuille hands and a salmon dial.

The reference H40 was equally split between seven monopusher versions and seven two-pusher references. Note that Roger Dubuis was the only brand creating a Lemania 2310-based monopusher chronograph during this period. While the monopusher is perhaps more unique, because of its strong association with the Patek 1463 Tasti Tondi, we love the two-pusher version.

Roger Dubuis made the Hommage chronograph in 3 different sizes 34mm, 37m and 40mm. Note that there are specific dials used for specific cases. 34mm and 37mm (H34 and H37mm) respectively use Sector or Scientific Dials influenced by the Patek reference 130 in design.

The Sympathie Chronograph

While the Hommage could be seen as Dubuis playing by the rules of traditional Swiss watchmaking, the Sympathie is where he started to think outside the box and push boundaries a little bit. With its angular square case and elongated lugs this was a watch with a unique silhouette to say the least.

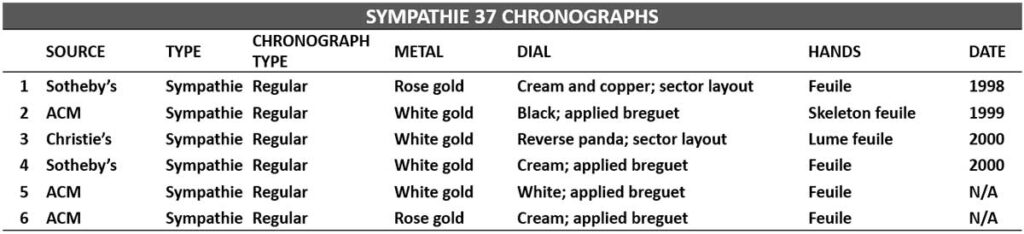

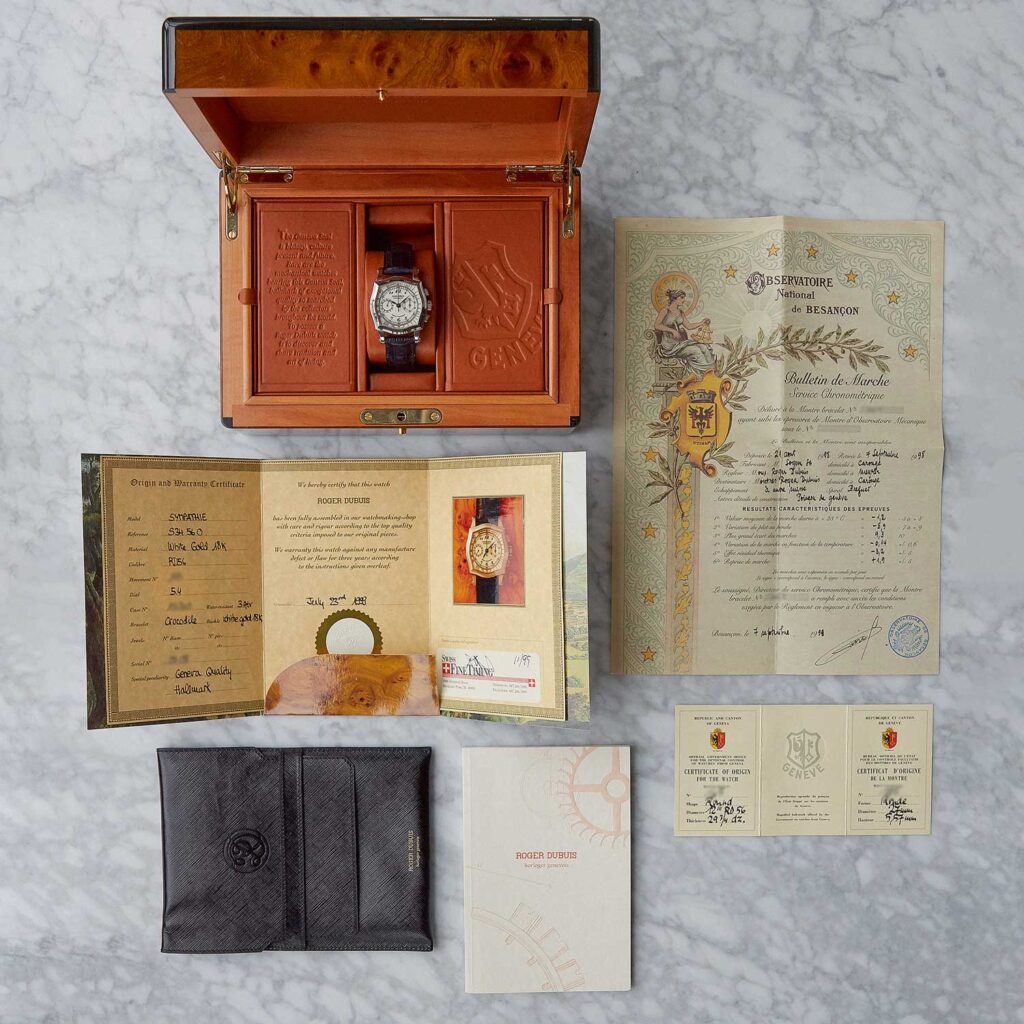

Unlike the Hommage, you’ll only find the Sympathie chronograph in cases sized 37 and 34 millimetres, with only white and rose gold cases publicly known. With far fewer dial variations to have appeared, they were either produced in more limited numbers or there have just been fewer that have come to market when compared with the Hommage chronographs. Here is a rundown of every publicly known configuration, drawing upon the same sources as the Hommage Chronographs discussed earlier.

The Sympathie chronograph only came in two sizes, 34mm and 37mm, unlike the Hommage, which also came in 40mm

The Movement

These two register chronographs from Roger Dubuis are powered by the Calibre RD 56 (for the regular version) or the RD 65 (for the monopusher version), both of which are based on the venerable Lemania ébauche 2310. This was a chronograph movement developed in 1942 in a partnership between Lemania and Omega. Omega called their version of the movement the Calibre 321, which you may know as the movement that went to the Moon.

The 2310 is a column wheel design with a screwed balance that oscillates at 18,000 A/h. While today watch brands make a big fuss about developing movements entirely in-house, it was once thought of as best practice to outsource a high-quality ébauche that had been designed and created by highly skilled and specialised movement makers. If you only do one thing, you tend to end up doing it quite well. In fact, a lot of collectors will still look back with nostalgia on Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronographs (the jewel of the brand’s catalogue) that were based on Lemania movements. As you can see below, there is a stark similarity between the Hommage’s movement and that of the Patek Philippe 3970, both of which use a Lemania 2310 ébauche.

This side-by-side comparison is just what Dubuis was after with these watches. It is as obvious in the choice of ébauche as it is in the level, quality and style of finishing that he put into these early models. He employed the finishing techniques that made Patek Philippe movements so desirable such as Côtes de Genève, mirror polishing and anglage. All things that helped the movement be awarded the Poinçon de Genève.

Movement side of an H34 Chronograph (left) and a Patek Philippe 3970 (right).

The Poinçon De Genève

A certification that at the time was only achieved by Patek Philippe watches, the Geneva Seal is unique in its accreditation as it doesn’t give much credence to measuring time correctly (that’s what the Besançon Observatory certification is for) but rather the art of decorating a movement with finesse and skill, which is something that the brand Roger Dubuis has prided itself on achieving since its foundation. Nowadays, you will find it stamped on the movements of brands such as Cartier, Chopard and Vacheron Constantin, as well as modern day Roger Dubuis. To achieve the certification, it requires the adherence to 12 criteria that are demanding for even the most skilled watchmakers, covering everything from the movement’s conception to how it has been finished.

The technical requirements of the seal are:

Good workmanship on all parts of the calibre. Steel parts must have polished angles and their visible surfaces smoothed down. Screw heads must be polished with their slots and rims chamfered.

Jewelling

• The entire movement must be jewelled with ruby jewels set in polished holes including the going train and escape wheel.

Regulating system.

• The hairspring should be pinned in a grooved plate with a stud having rounded collar and cap. Mobile studs are permitted.

• Split or fitted indexes are allowed with a holding system except in extra-thin calibres where the holding system is not required.

• Regulating systems with balance with radius or variable gyration are allowed.

Wheels

• The wheels of the going train must be chamfered above and below and have a polished sink. In wheels 0.15mm thick or less, a single chamfer is allowed on the bridge side.

• In wheel assemblies, the pivot shanks and the faces of the pinion leaves must be polished.

Escapement

• The escape wheel has to be light, not more than 0.16mm thick in large calibres and 0.13mm in calibres under 18mm, and its locking-faces must be polished.

• The angle traversed by the pallet lever is to be limited by fixed banking walls and not pins or studs.

Shock Protections

• Shock protected movements are accepted.

Winding Mechanism

• The ratchet and crown wheels must be finished with accordance with registered patterns.

Springs

• Wire springs are not allowed.

Ticking all of these boxes placed these movements in a rather exclusive club in 1995. It could be imagined that this level of finishing was only possible because of their small production numbers allowing them to spend more time on each component.

The Besançon Observatory tested completed watches while the industry standard COSC tested movements, a sure sign that Dubuis and Dias were trying to one up their competition

The calibre RD56 on Tom Chng’s H34

The back of an Hommage Chronograph

The pushers of the Hommage Chronograph are reminiscent of a Patek Philippe ref. 1463 ‘Tasti Tondi’

The Set

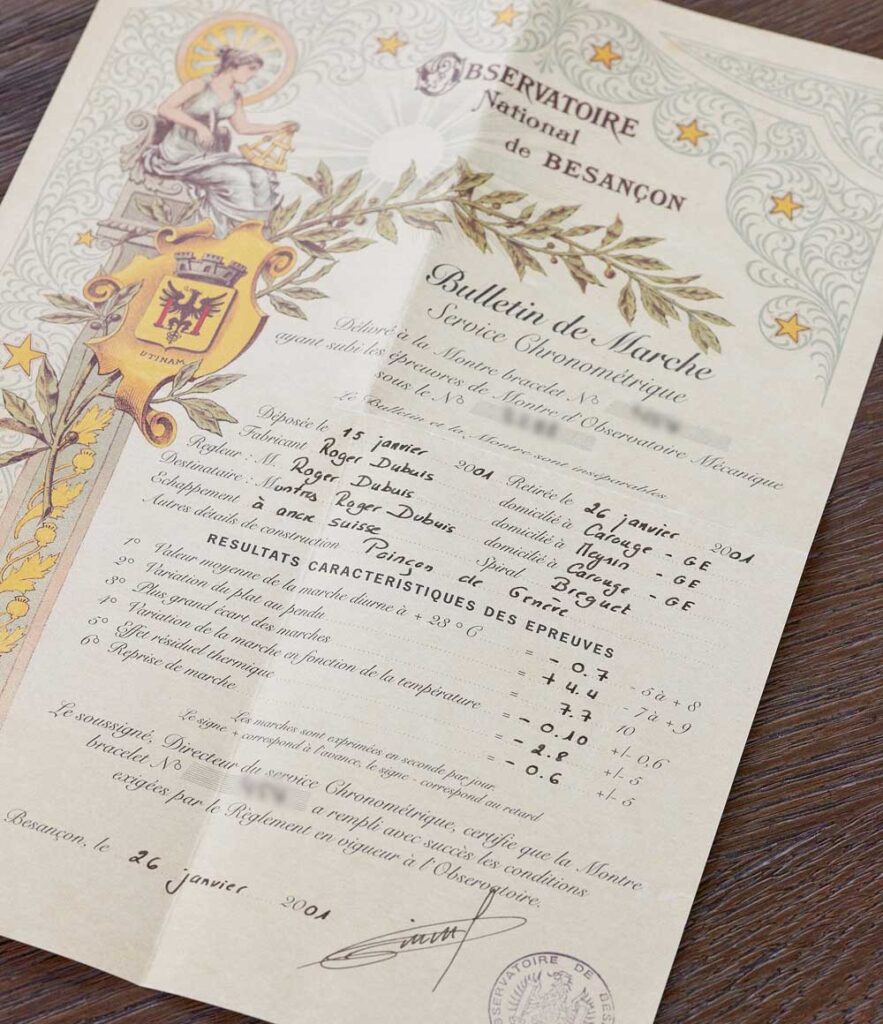

If you hang around a group of collectors long enough, you’ll more than likely hear one of them mention “The Set” or “The Full Set” when it comes to their vintage collection and it is something that those who collect these early Roger Dubuis pieces find extremely attractive when looking to acquire an example. For those looking to track down one of these early Roger Dubuis watches, it can be helpful to know what it should come with as well.

One notable element of “The Set” is the additional closed caseback that was included with all of Roger Dubuis early models. They came fitted with a sapphire caseback but if you didn’t want to see the finely finished movement, you could get a watchmaker to swap the backs for you. Although we are yet to have handled any models which have had this fitted to the watch when it arrived to us. Then again, you can’t really blame the previous owner, can you? It’s worth noting here that the only other brand to do this at the time was Patek Philippe. Though it is unconfirmed exactly why this was done, it is thought that this was a nod to the great watches of the past, where the true beauty of the movement was hidden away. Indeed, there is a certain elegance to concealing such finesse and craft, with satisfaction coming purely from knowing it’s there.

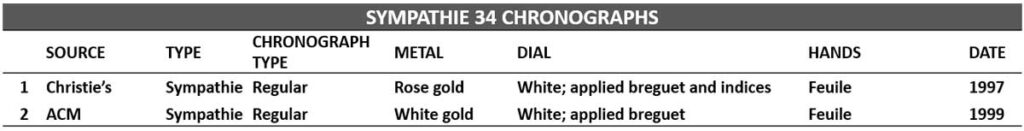

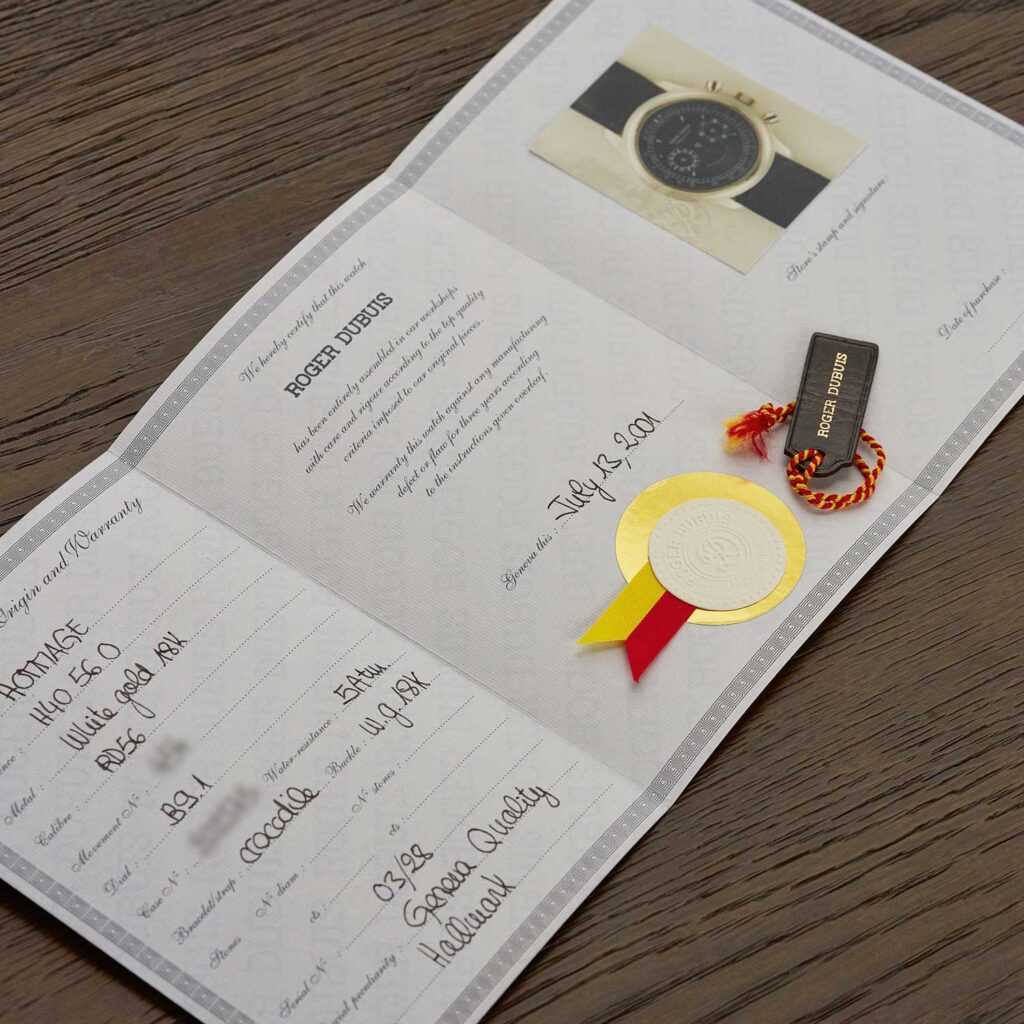

Alongside the caseback, there was an array of paperwork that came with the original box. The main pieces of literature that should be included are an Observatory certificate from the Besançon Observatory, a small Certificate of Origin that will show the Poinçon de Genève and a slightly larger Certificate of Guarantee which will hold all the information about your specific piece. Including case number, movement number (which should correspond to what is stamped on the watch) and the original date of sale alongside an image of the watch.

You should also see a leather folio, instruction booklet and a small blue booklet with Dubuis’ portrait on it providing some information about the company. Rarely kept, alongside the paperwork there should be a metallic Geneva Seal hang tag and a small leather hang tag that might have a label stuck to it indicating the model number. You should also hope to see either an original pin buckle or folding clasp attached to the leather strap even if the leather strap is no longer original. This is what all of that looks like.

You’ll notice that the Besançon Observatory certificate is far larger than any other piece of paperwork that is included with the watch and that gives some indication of how important and hard to come by such accreditation was. Setting far more exacting standards than a COSC test, the Besançon Observatory still demands the same standards as laid out by ISO 3159 that other chronometers had to go through, but it also demands that all watches arrive for testing fully cased and in their final form. Then they undergo 16 days of consecutive testing in five different positions at three different temperatures ranging from 8°C to 23°C and finally 38°C.

If, after all of that, the rate of time loss is within -4 to +6 seconds, it is stamped with the observatory’s famous viper and can be called an observatory chronometer. On the certificate that comes with your watch you will see the exact results your timepiece produced while undergoing these tests along with the date at which it passed.

A full set Roger Dubuis Sympathie (Image: Watchclub)

A Roger Dubuis Certificate of Origin and Guarantee from 2001

A very early Certificate of Origin and Guarantee from 1998, with Roger Dubuis’ signature on the Certificate of Origin and Guarantee

Community Participation

All of the data that we’ve presented here has been collected by A Collected Man and in no way do we want to proclaim that it is an exhaustive list but we do hope that it serves as a reference point for when you’re starting or expanding your collection, or even just to understand the very beginnings of early Roger Dubuis. We invite you to compare the records with your own collection to see if we have missed out anything. We would like to thank Helmut Crott, Su Jiaxian, Jason Singer and Mikael Wallhagen for their help in putting together this article.

For the Original Version of Posted by A Collected Man, click here.

To read other articles from A Collected Man’s repository of extensive research, click here.