An Odyssey Through Grand Seiko

News

An Odyssey Through Grand Seiko

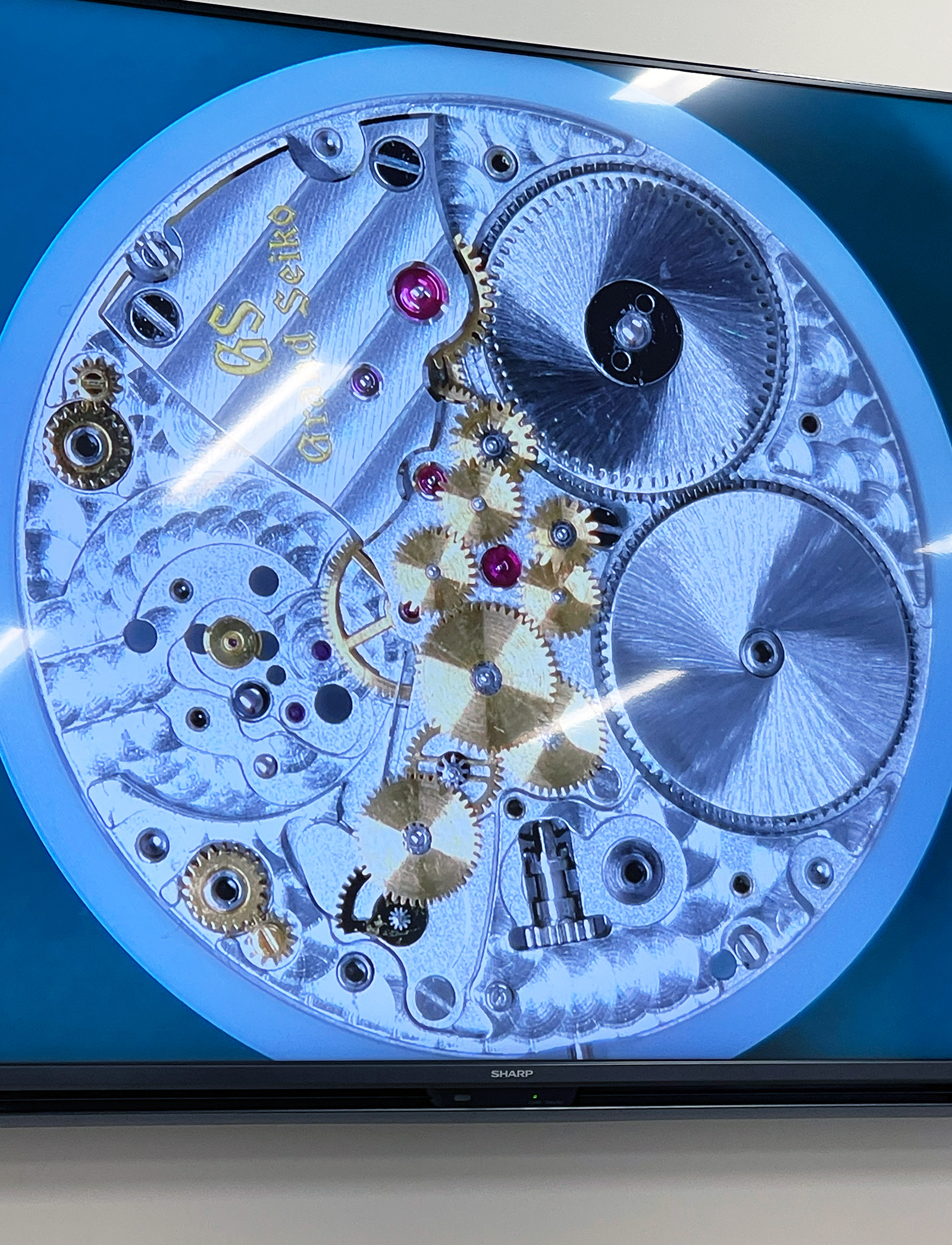

Grand Seiko has been known for the exceptional quality of its cases, dials and movements pretty much since its inception. But what has rapidly evolved since becoming independent from Seiko in 2017 is the trajectory of its ambitions, having ventured into realms few could have predicted. The main event was the launch of the Caliber 9SA5 in 2020, which brought a new escapement into an industrial reality. This was immediately followed by the release of the Kodo Constant-Force Tourbillon with a co-axially integrated remontoir and tourbillon, the most complex and costly Grand Seiko watch ever produced. Thereafter came the release of the Tentagraph, the brand’s first mechanical chronograph, built upon the sophisticated 9SA5, and then, the 9SA4, its first manually wound high-frequency movement in over 50 years.

I have found these releases so irresistible that it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that this time has led to a personal realisation. One of the questions I’m often asked is, “Which is your favorite luxury watch brand?” It’s a straightforward question that calls for a simple, direct answer. But the word “brand” always gives me pause. While it’s easy to rattle off a wish list of watches at any given moment, a brand is more than any one watch; it’s about watches that span categories and price points, its values and philosophy and how these translate into production methods and innovation, its consistency, its history, its achievements and the way it evolves over time. For years, no brand fully captured the varied aspects of watchmaking that has made the subject fascinating to me or brought them together in a way that truly resonated. As a result, a watch-by-watch appreciation came naturally, valuing the merits of individual creations over the brand on the whole — a mindset that felt both practical and fitting for any watch writer.

But over time, one brand began to eke out quite a presence within my personal collection, and that brand was Grand Seiko. It approaches every aspect of watchmaking with the same rigor – from dial, case to movement, from design, construction to finishing, from quartz and Spring Drive to mechanical watches. Few brands operate with such breadth, and even fewer with such depth. Admittedly, my unmitigated love for the brand has made writing about it quite challenging; maintaining even a modicum of objectivity feels nearly impossible, yet holding back seems equally disingenuous. Against this backdrop, the opportunity to visit Grand Seiko’s manufacturing facilities in Japan couldn’t have come at a better time.

Over the course of a week, a group of fellow journalists and I had the privilege of visiting three Grand Seiko facilities in Japan. Our journey began at Atelier Ginza, located on the seventh floor of Seiko House in Ginza, Tokyo, where the brand’s most complicated watches are assembled and adjusted. We then visited the Shinshu Watch Studio, nestled within the Seiko Epson facility in Shiojiri, Nagano Prefecture, home to Grand Seiko’s Spring Drive and 9F quartz watches, as well as the mythical Micro Artist Studio. Finally, we visited Studio Shizukuishi in Iwate Prefecture, where Grand Seiko’s 9S mechanical movements and timepieces are manufactured.

Right off the bat, it must be said that there is a huge difference in the way Grand Seiko conducts its tours. It’s tempting to attribute this to Japanese culture, with its deep-rooted values of hospitality, precision and respect for tradition, but this risks overlooking the individuality and agency of Grand Seiko. Each facility visit began with a sit-down theory session, which provided an in-depth understanding before the tour itself. Incredibly, we were even given multiple pages of notes at each site. Afterward, department heads, movement designers, watchmakers and other specialists were available to answer further questions, making the experience both comprehensive and enriching. This contrasts sharply with the typical manufacture visit, where you’re often rushed through the facility with little time to absorb the details, and the tour itself feels like a cursory obligation slotted into someone’s spare time — sometimes even leaving you with the sense that you’re intruding. At Grand Seiko, it felt as though the entire Seiko Group was not only aware of your visit but that every department and individual made a conscious effort to ensure the experience was both educational and meaningful. This truly stood out and gives weight to the adage: how you do anything is how you do everything. Whether it’s explaining technical minutiae, demonstrating techniques or patiently addressing even the most niche questions, every aspect of the tour reflects a sense of purpose and rigor.

Atelier Ginza

On Day 1, we arrived at Seiko House Ginza, formerly known as the Wako Main Building — a cultural landmark in Tokyo that holds deep significance not only for Seiko but also for Japan at large. The original building, crowned with its iconic clock tower, was completed in 1894 following Kintaro Hattori’s acquisition of the Choya Shinbun newspaper office. In 1921, it was dismantled to make way for a more modern, fire-resistant structure. The current neo-Renaissance building, designed by Jin Watanabe, was completed in 1932 after delays caused by the Great Kantō Earthquake. Remarkably, it survived World War II with only minor damage, unlike much of Ginza. During the Allied occupation, it served as a military post exchange before being returned to Wako in 1952, resuming its role as a luxury retail store. The clock tower, preserved through each transformation, became a cultural icon, even appearing in the 1954 film Godzilla. In 2022, on its 90th anniversary, the building was relaunched to serve as a communications hub for Seiko Holdings group, becoming Seiko House Ginza.

Today, the building continues to operate as a retail space, housing the Wako store from the newly renovated basement to the fourth floor, while the upper floors serve as a venue for exhibitions and events for Seiko. On the seventh floor is Atelier Ginza where a small team of elite watchmakers come together to design, assemble and adjust complicated masterpieces. It is where Grand Seiko’s most ambitious horological achievement, the Kodo Constant-Force Tourbillon is assembled and adjusted. While the majority of its components were produced at Studio Shizukuishi in Morioka, the final assembly and adjustment takes place in Atelier Ginza, within a humidity- and temperature-controlled clean room equipped with an air shower.

Surrounding the atelier is a display showcasing the evolution of the Kodo, from its early proof-of-concept — an elongated movement made from existing Grand Seiko parts with a key-wound barrel — to the T0 concept movement, and ultimately to the Caliber 9ST1 inside the SLGT003 “Kodo,” along with the GPHG Chronometry Prize it earned in 2022.

Takuma Kawauchiya, the mind behind the Kodo, was on-site that day to present the same lecture he had just delivered to the Swiss Chronometry Society. The highly complex Kodo, despite diverging significantly from the price point and class of traditional Grand Seiko watches, feels like a natural evolution given the brand’s deep-rooted history in precision chronometry. From its dominance in Swiss observatory trials in the late ’60s to pioneering Spring Drive, quartz and Hi-Beat movements, Grand Seiko has long concerned itself with precision timekeeping and, collectively, these different categories of watches demonstrate the different paths to chronometry, with the latest chapter being the most complex, traditional yet unbelievably innovative.

Creating the Kodo Constant-Force Tourbillon

Chronometric performance is dependent on numerous factors, including balance inertia, oscillation frequency, the stability of a free-sprung balance, torque consistency throughout the power reserve, escapement efficiency, isochronism, finishing, assembly, positional adjustments and fine regulation. A deficiency in one area can, to some extent, be offset by advanced materials or excellence in another, and thus, there are varied approaches to achieving precision in modern watchmaking. The beauty of the Kodo lies in the continued ingenuity applied to some of watchmaking’s oldest solutions to its oldest challenges — the tourbillon, addressing positional rate variations and the remontoir, ensuring constant energy delivery to the escapement and balance throughout the course of its power reserve.

The manner in which they are combined — integrated on the same axis as one unit — also addresses potential drawbacks in prior configurations that have sought to merge the two regulating devices. Simply put, if a remontoir is positioned within the gear train of a tourbillon movement, it must overcome the inertia of the subsequent wheels and the cage, while also contending with power loss due to friction. “The initial goal was to put the two mechanisms as close together as possible to eliminate any gears or parts in between as even one wheel will affect the accuracy,” says Kawauchiya.

In the Kodo, the remontoir is built with its own cage that houses the tourbillon carriage on the same axis. The remontoir delivers power directly to the tourbillon, which drives the escape wheel against a fixed wheel, eliminating a host of variables that could cause fluctuations in rate. The outer remontoir carriage comprises of an integrated remontoir wheel (driven directly by the going train), a ceramic ratchet stop wheel that rotates against the fixed fourth wheel and a remontoir spring. As the inner tourbillon cage rotates with the remontoir carriage, a stopper, with a jewel pallet attached to the tourbillon, brakes the ratchet stop wheel every second, creating a snapping motion. Every second, the stopper releases the stop wheel, allowing the remontoir spring to unwind momentarily, driving the entire remontoir cage forward in a controlled step until the stop wheel meets the stopper again, locking the mechanism. This precise release allows the remontoir to function as a deadbeat second, while the tourbillon cage, which houses the escape wheel, rotates continuously within the remontoir assembly, creating a contrast of motions. The performance of the Kodo over the 50-hour running time during which the remontoir is engaged is very impressive — ±1 second maximum deviation in rate per day and an amplitude fluctuation of within ±5 degrees.

Kawauchiya was a professional guitarist for 10 years before transitioning to watchmaking. At the age of 29, his rock band disbanded, prompting him to change career paths. Following a suggestion from his mother, he enrolled in Tokyo Watch Technicum, a Rolex-operated, WOSTEP-accredited watchmaking school in Japan, and upon graduation, joined Seiko in 2010. He worked in the R&D department for about a decade before joining the Movement Design and Engineering Division in 2018.

“As an engineer, I pursue functionality such as precision or durability, things that can be expressed in numbers but as an artist I pursue elements that appeal to people’s emotions such as the appearance or the watch or the sound of the watch. My journey was a process of harmonising my engineering and artistic voices, which resulted in the Kodo Constant-Force Tourbillon,” says Kawauchiya.

He shed light on the many finer points of the Kodo. One thing I had never given a moment’s thought to was just how much effort was required to synchronise the escapement and remontoir. In theory, a one-second remontoir should release energy once every eight vibrations of the escapement, creating a perfectly regular rhythm akin to a 16th-note subdivision in music. Yet, in practice, even the slightest eccentricities in gears, minute misalignments in axes or microscopic clearances in jewel holes disrupted this timing. Instead of engaging predictably after eight vibrations, the remontoir might release after seven or nine, introducing subtle but critical inconsistencies that made it difficult to hear a clean and precise 16th-note cadence. Unlike traditional remontoirs, where such variations might go unnoticed, the Kodo’s mechanism produces a distinct and audible ticking, making any deviation perceptible to the ear. Achieving absolute consistency demanded an extreme level of dimensional accuracy in machining, ensuring that each component functioned with near-perfect precision. In practice, the tolerances had to be twice as tight as the usual. “In addition, a mechanism was included to adjust the precision of the stopper in case the resulting sound still deviated from the correct position. The goal is to adjust the stopper until Kodo achieves the perfect beat,” says Kawauchiya.

Additionally, a frequency of 4 Hz is particularly high for a movement that has both a tourbillon and a remontoir. Kawauchiya explains, “A 4 Hz movement requires more than twice the energy of a regular 2.5 Hz watch. Therefore, combining a 4 Hz balance with the remontoir and tourbillon requires more than five times the energy of a 2.5 Hz watch. It increases the gear train load and the risk of component wear. This is why there has not been a combination of the constant-force mechanism with a balance frequency of 4 Hz or higher.”

“However, I insisted on using 4 Hz (eight vibrations per second) not only for the functional value but also for the emotional value of sound,” he continues. “Through the following efforts, I succeeded in avoiding wear. In the constant-force mechanism, the collision and sliding action of the stop wheel and stopper, generate an oversized load. Therefore, I utilised ceramic as the material of the stop wheel as it can withstand strong impact and friction. However, using a material like ceramic, which is very difficult to machine as you can imagine, demands high dimensional accuracy. It was a significant challenge. In addition, the high torque of the mainspring required the gear train to be robust. We applied a highly wear-resistant coating to the second and third wheel, which are subjected to high stresses.”

The ceramic stop wheel in the constant force mechanism. It rotates against a fixed fourth wheel. Every second, a stopper with a pallet jewel attached to the tourbillon releases the stop wheel, allowing the remontoir spring to unwind momentarily, driving the entire remontoir cage forward in a controlled step until the stop wheel meets the stopper again, locking the mechanism.

After the session at Atelier Ginza, we headed to the sky garden to see the iconic clock. While the tower has withstood many transformations since 1932, the clock itself has evolved significantly over time. It was originally a mechanical clock with Westminster chiming, powered by a weight winding system, but later in 1966 it was converted to a Seiko quartz movement. In 1974, that first quartz movement was replaced with an even higher-precision quartz movement to ensure more accurate timekeeping. Finally, in 2004, a new GPS system was installed.

Later we headed to the Wako boutique on the ground floor, a spacious circular showcase for a wide range of brands such as Breguet, Glashütte Original, Piaget, Jaeger-LeCoultre as well as Grand Seiko. The second floor is a dedicated lounge showcasing high-end Grand Seiko pieces, Credor as well as an archival display. Notably, customers can order a bespoke Grand Seiko watch exclusively at this boutique. The watch has to be cased only in 18K gold or platinum cases and the process spans approximately 13 months from the initial consultation to delivery. On display were two bespoke variations of the Grand Seiko Spring Drive 8 Day SBGD201, which was initially launched in 2016 and was the first Grand Seiko produced by the Micro Artist Studio. Equipped with the Spring Drive 9R01 movement, the bespoke examples feature special dials and are priced at 16,500,000 yen, approximately CHF 96,920.

At our last stop in Tokyo, we visited the new Grand Seiko boutique in Omotesando, a tree-lined avenue, often referred to as Tokyo’s equivalent of the Champs-Élysées. It stretches from Harajuku Station to the entrance of the Meiji Shrine, serving as both a fashionable shopping district and a cultural landmark. Unlike traditional boutiques where timepieces are secured behind glass cases, the new boutique has an open display concept, which allows visitors to have direct, hands-on access to the watches. Adding to the immersive experience, the boutique features specially commissioned artwork and dynamic LED walls that showcase visuals inspired by nature, reflecting Grand Seiko’s deep connection to Japan’s natural landscapes and the seasonal inspirations behind their timepieces.

After a 3-hour drive from Omotesando, we arrived at our hotel in Kobuchisawacho, nestled in the highlands of Hokuto City, Yamanashi Prefecture, near the Nagano border, and settled in for the night.

Shinshu Watch Studio

The next day, we made a 50-minute drive to the Seiko Epson facility in Shiojiri, Nagano Prefecture. Within this facility lies the Shinshu Watch Studio, where Spring Drive, 9F Quartz, and the Micro Artist Studio coexist seamlessly. In lesser hands, such variety might seem conflicting, but here, it forms a very distinct, authentic character. The space feels raw and lived-in – not sterile or staged, but alive with continuous hands-on work.

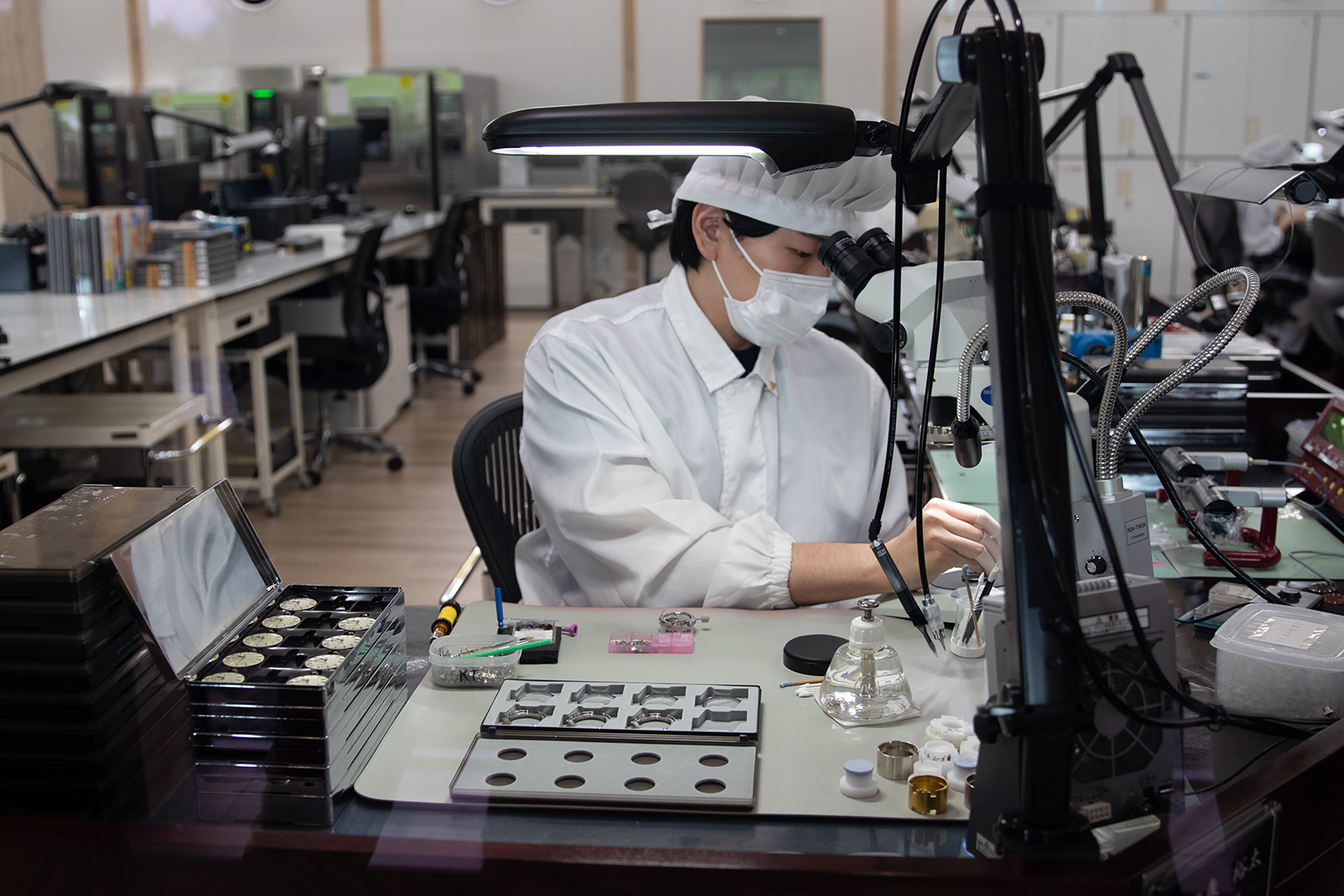

Terminology in watchmaking roles can be confusing, often conflated under the term “watchmaker.” However, a manufacture generally comprises engineers, artisans, specialised technicians and production watchmakers. At Grand Seiko, they are all referred to as Takumi, meaning artisan or craftsman. It embodies not just technical skill but a philosophy of mastery, dedication, and continuous improvement, qualities deeply embedded in Japanese craftsmanship.

This commitment to excellence is recognised through honours like the Yellow Ribbon Medal of Honor, awarded by the Japanese government to individuals who have demonstrated exceptional skill and dedication in their craft. Some of Grand Seiko’s Takumi have received this prestigious award, underscoring their status as custodians of traditional crafts and role models within their profession. Moreover, some employees have also medaled in the International Skills Olympics (WorldSkills Competition) for watchmaking, showcasing their expertise on a global stage. The succession of skills is incredibly important to the company at large and it’s quite unusual. They have an internal ranking system that ensures not only are employees evaluated on their personal craftsmanship, but also on the proficiency of the subordinates they are responsible for training. This focus on mentorship and continuous development ensures that the spirit of Takumi is preserved and passed on.

The design, development and production of movements, cases, and dials, which include hands and indexes, along with assembly and adjustment of all Grand Seiko Spring Drive and 9F Quartz watches are all performed here before the completed watches are shipped to other parts of Japan and overseas.

Takumi Studio

The Takumi studio is a cleanroom where Spring Drive and 9F Quartz watches are fully assembled, from movement assembly to casing and bracelet attachment. Most modern movements in the industry today are products of sequential operations on an assembly line but every Grand Seiko watch, from assembly to final adjustment, is done by a single skilled watchmaker. This applies to Spring Drive. Quartz movement production is generally highly automated but at Grand Seiko, one watchmaker assembles the date indicator and the other the rest of the 9F Quartz movement.

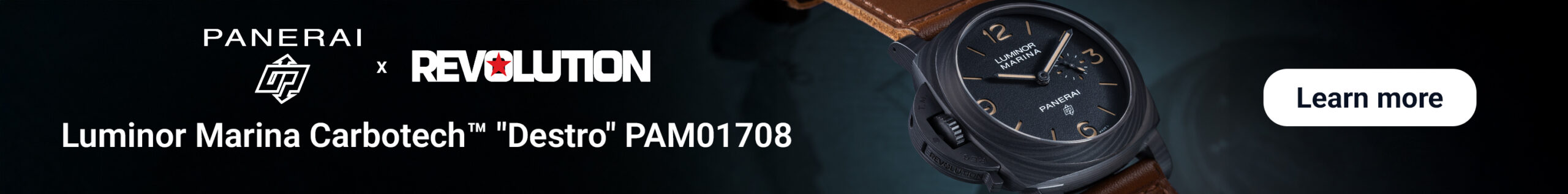

We got to observe a watchmaker fine-tune the hairspring in the backlash auto-adjust mechanism of a 9F Quartz movement. What’s most outstanding about Grand Seiko is its extraordinary attention to detail in every facet of its craft. When it comes to its quartz watches, it’s not just high accuracy that matters; how that performance is expressed visually on the dial is equally important. The movement is unusually sophisticated, incorporating numerous features traditionally associated with mechanical watches. In a quartz watch, because the motor is activated in discrete one-second pulses, there is a brief interruption in the energy transmission that can lead to slight mechanical play, or backlash, between meshing gear teeth. In contrast, a mechanical watch derives continuous energy from the mainspring, with the escapement regulating the release of that energy, resulting in a smoother operation with minimised backlash.

As such, there is a special gear along the going train in a 9F Quartz movement that is fitted with a coil hairspring to provide a small counterforce that keeps the gear teeth in constant, tight engagement, effectively minimising play between teeth. As a result, the action of the gear train is smoother, and the seconds hand lands precisely on the second markers each time. Additionally, the Twin Pulse Control Motor in the 9F Quartz movement is designed to handle greater torque. This design not only ensures that the seconds hand lands exactly on the second marker, but it also effectively handles the inertia of the larger, thicker hands characteristic of Grand Seiko’s watches.

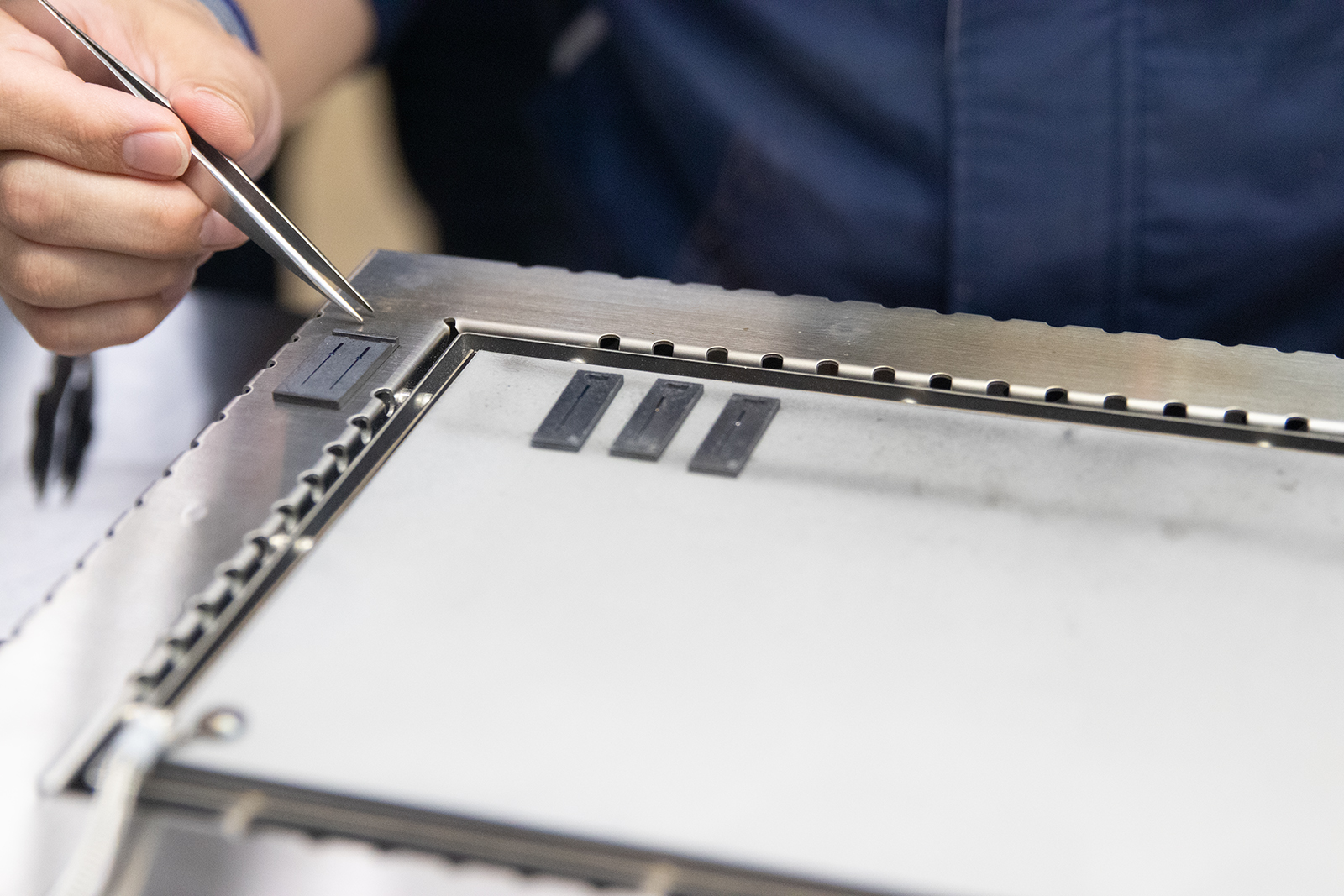

Next we saw a watchmaker installing the hands of a Spring Drive GMT. The hands are positioned in parallel within a tight 2mm space and are held in place by a friction fit resulting from being pushed onto the cannon pinion. Ensuring that all hands, separated by just 0.2mm, rotate smoothly without interference requires the skill of an expert in fine adjustments. To prevent any scratches or blemishes during assembly, the tips of the tweezers used are polished multiple times each day.

Moving along, we saw movements being cased and bracelets being attached. Traversing these corridors provided an insight into Japanese efficiency and precision, where artisans at their benches breathed life into watches with exacting care.

Case Studio

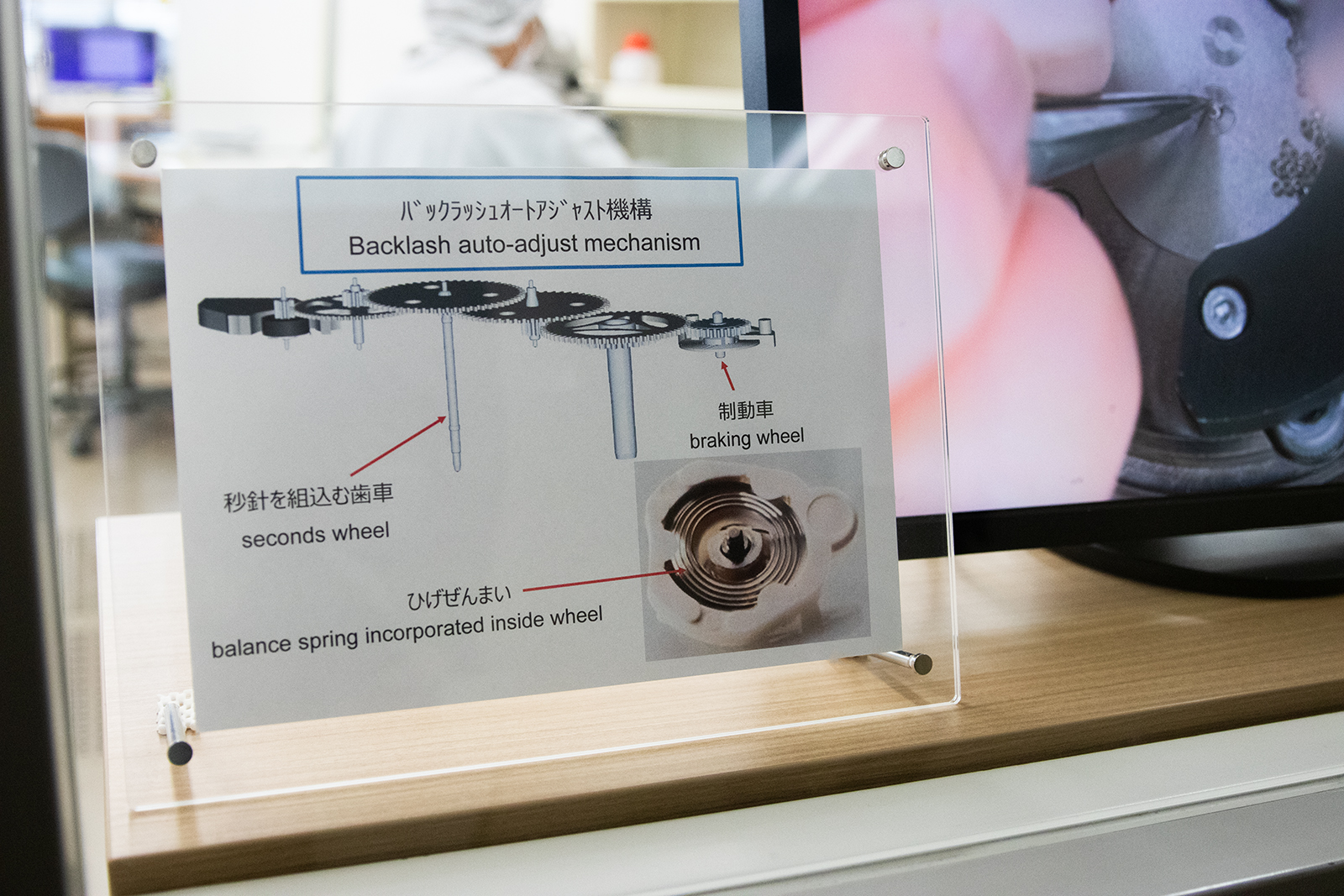

Grand Seiko’s strength as a watchmaker are many but one aspect that has gained the most renown is the quality of its cases. There are two different methods employed for case production at Grand Seiko: cold forging, primarily for gold and platinum cases and CNC-machining for titanium and steel cases.

Cold forging eliminates porosity, enhances strength, and enables sharper, more defined case geometries. Unlike hot forging, which requires heating the metal before shaping, cold forging is performed at room temperature with significantly greater force. The process involves placing a pre-cut metal blank into a die set, where a hydraulic press applies immense pressure, progressively shaping the metal into its final form through multiple forging cycles. After each forging, the case undergoes annealing at approximately 1,100°C to relieve internal stresses, preparing it for subsequent finishing operations.

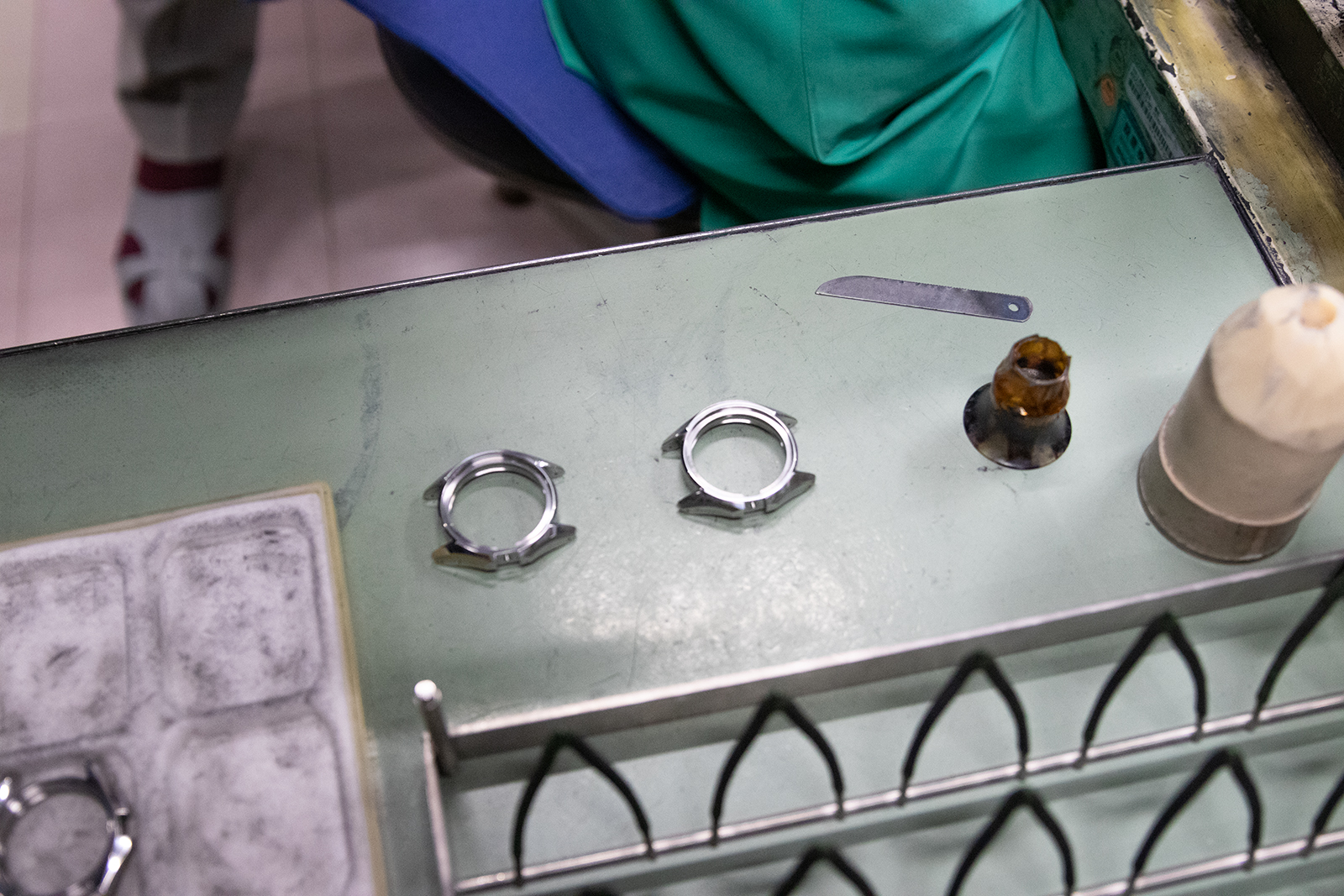

Case finish is a signature strength of Grand Seiko, and we got to witness the famous Zaratsu polishing. The difference between Zaratsu polishing and conventional polishing techniques lies in the method, precision, and final result. Traditional polishing typically involves pressing the case against the edge of a polishing wheel, a method susceptible to subtle surface inconsistencies due to variations in pressure and angle. By contrast, Zaratsu polishing uses the flat face of a rotating tin plate, precisely controlling the angle and pressure to create a flawlessly reflective surface free of distortion or waviness.

Executing Zaratsu polishing demands exceptional skill and precision, and the polished finish is then further refined through buffing with a soft cloth wheel, resulting in an exceptionally smooth and reflective surface.

Zaratsu polishing is often contrasted with hairline brushing, which serves as the final step in case finishing. The hairline finish is created by pressing and sliding the case against a metal plate covered with 400- to 800-grit sandpaper. The appearance of the hairline pattern varies depending on the pressure applied and the speed of movement, allowing for different textures.

For flat surfaces, the case is guided in a straight back-and-forth motion to ensure a uniform grain. In contrast, finishing curved surfaces demands a controlled rotational movement to maintain consistency across the contour. Since excessively deep hairlines cannot be corrected, precision is critical. In some areas, particularly those that require finer control, sandpaper is applied manually using a rod to refine the surface.

Dial Studio

Grand Seiko’s dial quality is equally exceptional, to the point that it makes the dials, hands and indexes of so many other luxury brands feel almost like an afterthought. Rolex is an exception but where Rolex excels in clinical perfection, Grand Seiko explores diverse, creative techniques to achieve highly nuanced effects, resulting in dials with a unique character and depth.

The creation of the famous “Snowflake” dial involves no less than nine steps from raw brass plate to completion. It begins with the stamping of the signature texture onto a dial blank with a hydraulic press that applies 200 tonnes of pressure. The moulds themselves are created by the Shinshu Watch Studio and they are engraved by hand. This is followed by silver plating to achieve a pure white base and the application of multiple layers of coating to achieve the delicate translucency that defines its final appearance.

The calendar window, power reserve indicator, or holes made for mounting the indexes are cut using a blade rather than a press die to maintain the integrity of the multi-layered dial and achieve a sharp, flat finish.

Then the lettering and minute track are pad printed, which is a very delicate process as the state of the ink changes with temperature and humidity. A craftsperson manually applies ink for each print into the recesses of an engraved plate and the excess is wiped off. Then a pad, made from powdered gelatin, picks up the print. The dial is then placed perfectly under the pad by hand.

After this is done, the indexes are applied by hand as well. Once the lettering is printed, the indexes applied, and the date window surround inserted, the dial’s ready to become part of the watch.

The indexes are cut using a diamond-edged rotary tool. A skilled technician manually operates the cutting machine, while carefully monitoring the process with a small hand mirror to ensure each index catches and reflects light exactly as intended.

We also got to observe the hand-bluing process. The artisan carefully places each hand on a hot plate, watching intently as it gradually shifts to the perfect shade of blue. There are no timers; a reference blued hand is placed nearby and serves as the benchmark for comparison. The artisan relies entirely on their trained eye, removing each hand at the precise moment it matches the reference.

Crafting a Snowflake dial is highly labour-intensive, yet in truth, it is representative rather than an exception at the Shinshu Watch Studio. The extensive handwork the goes into dials, hands, and markers contributes to the exceptional quality found throughout Grand Seiko watches.

Jewellery Studio

One of lesser-known aspects of Grand Seiko is that it has a full-fledged gem-setting department. In recent years, just as its technical ambitions soared, it expanded its focus on high artistry, elevating its dial and casework through intricate gem-setting techniques. These are six-figure watches in the Masterpieces collection such as the Spring Drive 8 Days SBGD205, SBGD20, SBGD213, SBGD209 and most recently the SBGD215.

Artisans in the jewelry studio work in dim lighting to reduce eye strain for prolonged precision work, with focused lights illuminating each workstation. Gem-setting is a craft that must be equated with the patience, the eye and the steady hand we take for granted in watchmaking.

Holes for diamonds and other gemstones are precisely drilled into the case, while a frame is carefully sculpted using a Japanese metal-carving technique. The bonds securing the gemstones are then crafted using Western engraving methods, such as pavé setting. Since every diamond has slight variations in size, the angle and height of each stone are individually adjusted before four delicate prongs are bent over to secure it in place.

Beyond Grand Seiko, the jewellery workshop is also responsible for Credor’s gem-set watches and has developed its own proprietary gem-setting technique, known as the Celeste setting. This method creates the illusion of diamonds floating, allowing light to enter from the top, sides, and bottom to enhance their brilliance. Additionally, the jewellery studio handles the brazing of precious metal cases and bracelets.

Micro Artist Studio

The last stop of our tour at Shinshu Watch Studio was the Micro Artist Studio where the most complex, as well as the most technically and aesthetically sophisticated, Spring Drive watches are hand-finished and hand assembled by a small team of master artisans.

During our visit, we had the privilege of meeting the legendary Masatoshi Moteki, a key figure in the development of the Spring Drive, which is undoubtedly one of the great marvels in modern watchmaking. His expertise and rigor are nothing short of extraordinary. While the Micro Artist Studio is well known around the world for its impressive finishing, speaking to Moteki offered an insight into its technical genius.

The Micro Artist Studio was established in 2000 and it was in 2003 when Moteki joined the studio, becoming part of the team responsible for the Credor Spring Drive Sonnerie (2006) and Spring Drive Minute Repeater (2011). Both watches are some of the most unique chiming watches ever created and the only ones with a movement that is completely silent.

The Orin bell shaped both the technical and cultural philosophy behind the Sonnerie. Moteki explained, “In Japanese tradition, many of our houses have small Buddhist altars that usually have an Orin bell. If you go to a Japanese home, many people have these in their altars and they ring it. We created a miniature Orin bell to produce the beautiful sound in the Sonnerie.” Instead of gongs, a circular Orin bell covers the top plate of the movement and serves as the striking surface for the hour hammer. This design produces a pure, lingering resonance, capturing the essence of the Orin’s tranquil chime.

Additionally, the Spring Drive Sonnerie chimes three times every three hours (3 o’clock, 6 o’clock, 9 o’clock and 12 o’clock) in “Original” mode. The concept of a 3-hour interval mode is rooted in early Japanese cultural traditions, predating the adoption of standardised timekeeping. In premodern Japan, daily life followed a temporal hour system, where the length of hours changed with the seasons as daylight varied throughout the year. To mark key moments in the day, temple bells were sounded at regular intervals, serving as a communal time signal. Though the timing of these chimes was not fixed by today’s standards, historical records suggest that, when converted to modern timekeeping, the intervals between bell tolls often averaged around three hours. In Sonnerie mode, the watch chimes the hours automatically at the top of every hour and silent mode disables automatic striking. Additionally, it is an hour repeater, allowing the wearer to chime the hours on demand by pressing the pusher at eight o’clock.

The Credor Spring Drive Minute Repeater, on the other hand, features two gongs forged by Munemichi Myochin, a master craftsman from the Myochin family, which has been specializing in metalwork for over 850 years. These gongs are designed to replicate the resonant tones of a traditional Japanese wind chime. The minute repeater mechanism draws power directly from the twin mainspring barrels, without a dedicated repeater barrel. This is made possible by a one-way clutch and the purpose of this configuration is to provide a longer power reserve. Traditionally, minute repeaters have a short power reserve; the barrel has to be small as the movement has to accommodate a repeater barrel. The Credor Minute Repeater is also decimal minute repeater, where the snail for the minutes has six arms with 10 steps that encodes 0 to 9 minutes, and the quarter snail is replaced by a tens of minutes snail that has six steps for 0 to 5.

The most unique aspect of the Credor Sonnerie and Minute Repeater are their completely silent movement, ensuring that nothing interferes with the clarity of the chimes. The governor at the end of the striking gear train relies solely on air viscosity rather than friction to create resistance and is thus completely silent. It consists of two crescent-shaped blade wings and two guiding plates. When assembled, they appear circular in plan view. Each wing has a post on which a zigzag spring is hooked. The other end of the zigzag spring is attached to the guiding plate. Notably, each wing has a finger on its inner end that will contact a post on the guiding plate to limit is movement. The entire governor is located between two plates with a circular cut-out. As its wings expand outside of their guiding plates and into the gap between these two plates, they are subject to greater resistance due to air viscosity and this causes their speed to drop. As their speed decreases, the zigzag spring pulls the wings back in towards the guiding plate. In addition, as the Spring Drive’s Tri-synchro regulator is totally silent, without the characteristic tick tock found in a regular escapement, it makes for some of the most purest sounding chiming watches.

After the session with Moteki, we proceeded to the part of the studio where dials are crafted. The artisans were working on the blue and white porcelain dials of the Credor Eichi II.

Unlike enamelling which uses a metal base, often copper or gold, a ceramic base is used for porcelain dials. The lapis lazuli-colored porcelain dial undergoes a meticulous multi-step process to achieve its deep blue hue and precise detailing. It begins with the porcelain base, which is coated with a durable alumina enamel glaze. This glaze, containing aluminum oxide, enhances the dial’s resistance to discoloration and scratches, ensuring long-term durability while maintaining a smooth, refined finish. Once the base is prepared, a transfer sheet containing the logo and indexes is applied. This screen-printed decal allows for precise and consistent placement of the markings, similar to techniques used in fine ceramic and glasswork. The dial is then fired at approximately 800°C, fusing the transfer sheet’s details into the enamel glaze, embedding them permanently.

After this initial firing, the logo and indexes are hand-painted over the markings. Using a carefully mixed blend of four pigments, diluted with oil, the artisans meticulously paint each element with a fine brush, ensuring crisp and uniform markings. The dial then undergoes a final firing, which permanently bonds the hand-painted details to the surface. The indices are about 0.2mm in height after being painted and fired, adding dimension to the dial.

There was a picture of Philippe Dufour overlooking the workshop – a fitting tribute to the master watchmaker who once guided the Micro Artist Studio in the art of movement finishing. His influence remains evident in Grand Seiko’s high-end creations such as the Calibre 9R02, which represent some of the finest hand-finishing in the business.

Studio Shizukuishi

After a nearly three-hour train ride from Nagano on day two, we arrived at our hotel in Morioka and rested for the night. The following day, we headed to Studio Shizukuishi, a purpose-built facility dedicated to the assembly and testing of Grand Seiko’s mechanical watches. Opened in July 2020 to commemorate the brand’s 60th anniversary, the studio was designed by renowned Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. It is situated alongside the existing Morioka Seiko Instruments Inc. facility where Grand Seiko’s mechanical watches were previously produced. While the new studio focuses on the assembly, adjustment and regulation of Grand Seiko mechanical watches, the fabrication of individual components continues at the adjacent Morioka Seiko Instruments facility. This separation ensures that each aspect of watchmaking, from component production to final assembly, is conducted in environments tailored to their specific requirements.

For nearly 50 years, Morioka Seiko Instruments Inc. has called this land home, drawn by its ideal setting for watchmaking. There are 700 employees in the Morioka facilities including Studio Shizukauishi. With one-third of the site covered in nearly 1,000 wild-grown trees, Studio Shizukauishi is a space where industry and nature thrive together. It is modern yet serene, designed to harmonise with the surrounding landscape rather than impose upon it.

Our guide, General Manager Yoshihiro Kubo, led us through the studio, sharing insights into its philosophy; the integration of tradition with innovation, nature with industry. The studio is one of the most impressive environmentally conscious watch manufactures. The enormous amount of thought, effort, and investment in sustainability was an unexpected component that left a lasting impression.

To minimise waste and optimise resource use, the studio follows the Reduce, Reuse, Recycle framework. Water conservation plays a key role, with a dedicated wastewater treatment system allowing water to be reused throughout production. Energy efficiency is enhanced by the studio’s in-house wireless sensor network, “Mr. Sho-Ene,” which monitors temperature, humidity, and power usage to reduce consumption. Additionally, the facility adheres to strict CO₂ reduction targets, continuously refining its processes to minimise emissions.

A major aspect of the studio’s sustainability efforts is solar energy. Solar panels installed on the roof generate electricity that exceeds the studio’s annual consumption, ensuring a net-positive energy balance, even in winter when sunlight is reduced.

Beyond that, Studio Shizukuishi actively preserves local biodiversity. Every tree in its natural forest is registered and maintained, while bird and squirrel houses are installed to support local wildlife. Non-native species are monitored to prevent ecological disruptions, ensuring that the surrounding ecosystem remains undisturbed.

In August 2022, the studio expanded its environmental initiatives with the Waku-Waku Biotope, a 2,833-square-meter waterside ecosystem developed in collaboration with Iwate Prefectural University. Featuring a pond, wetlands, and a rain garden, the biotope uses a natural purification system that recycles rainwater collected from the factory roof.

Yoshihiro Kubo noted that the qualities of the local residents – patience and a longstanding tradition in handcrafts such as woodworking and ironworks – make them well-suited for watchmaking. More than 90% of employees are hired locally.

After exploring the studio’s surroundings, we made our way to the exhibition area in the facility. The walls of Studio Shizukuishi are adorned using the traditional Japanese Yamato-bari technique, where wooden boards gently overlap to create shadow and light within the space.

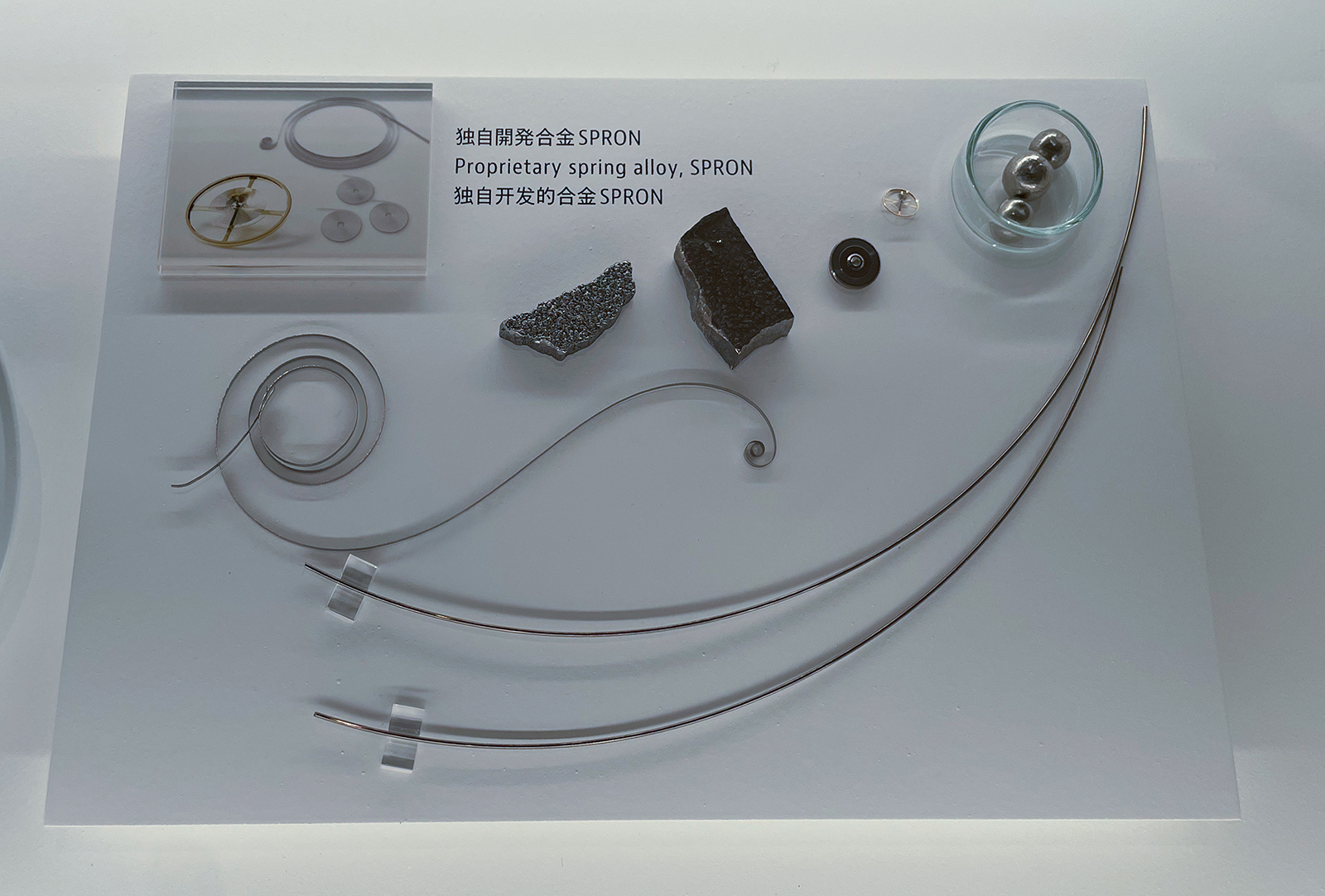

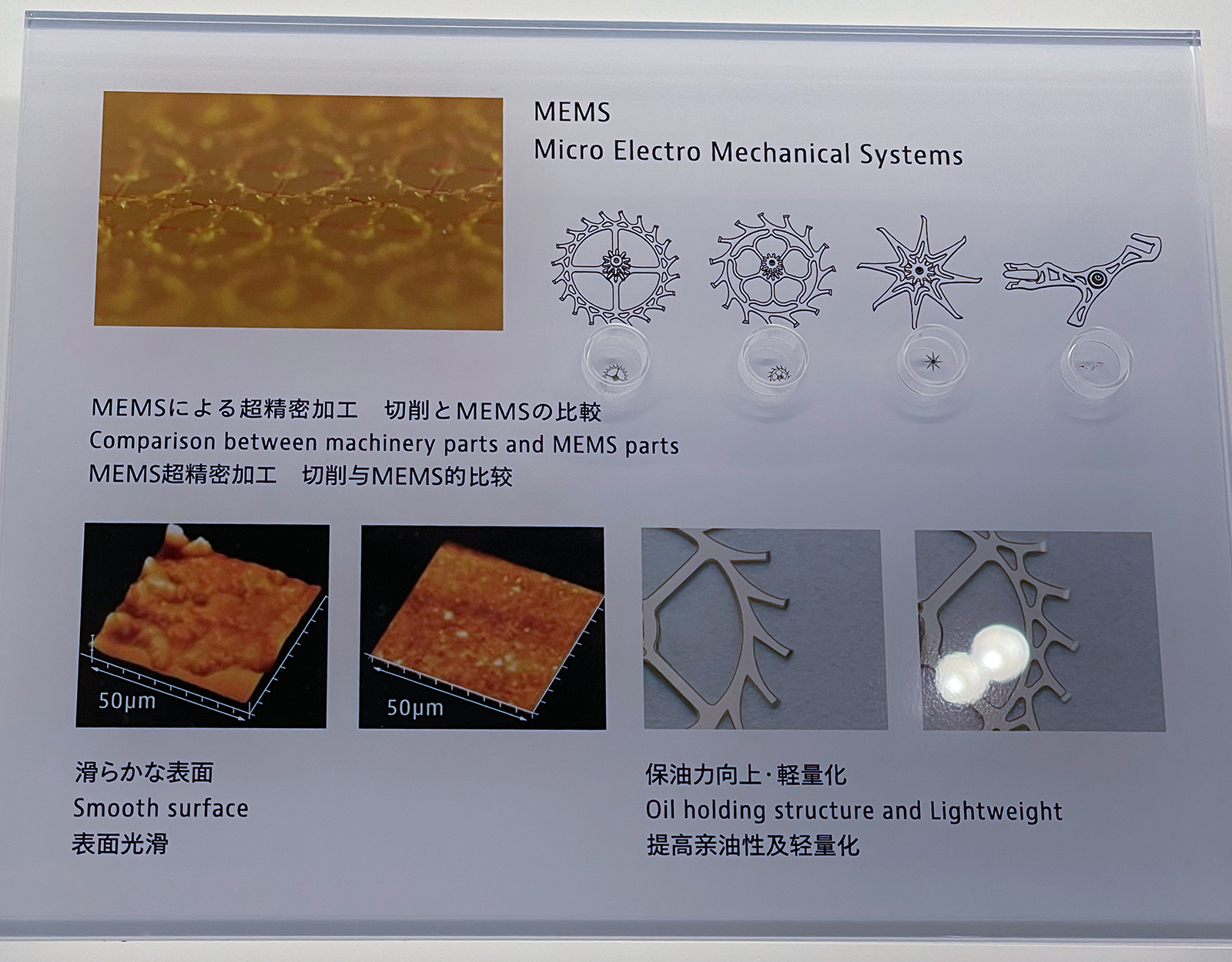

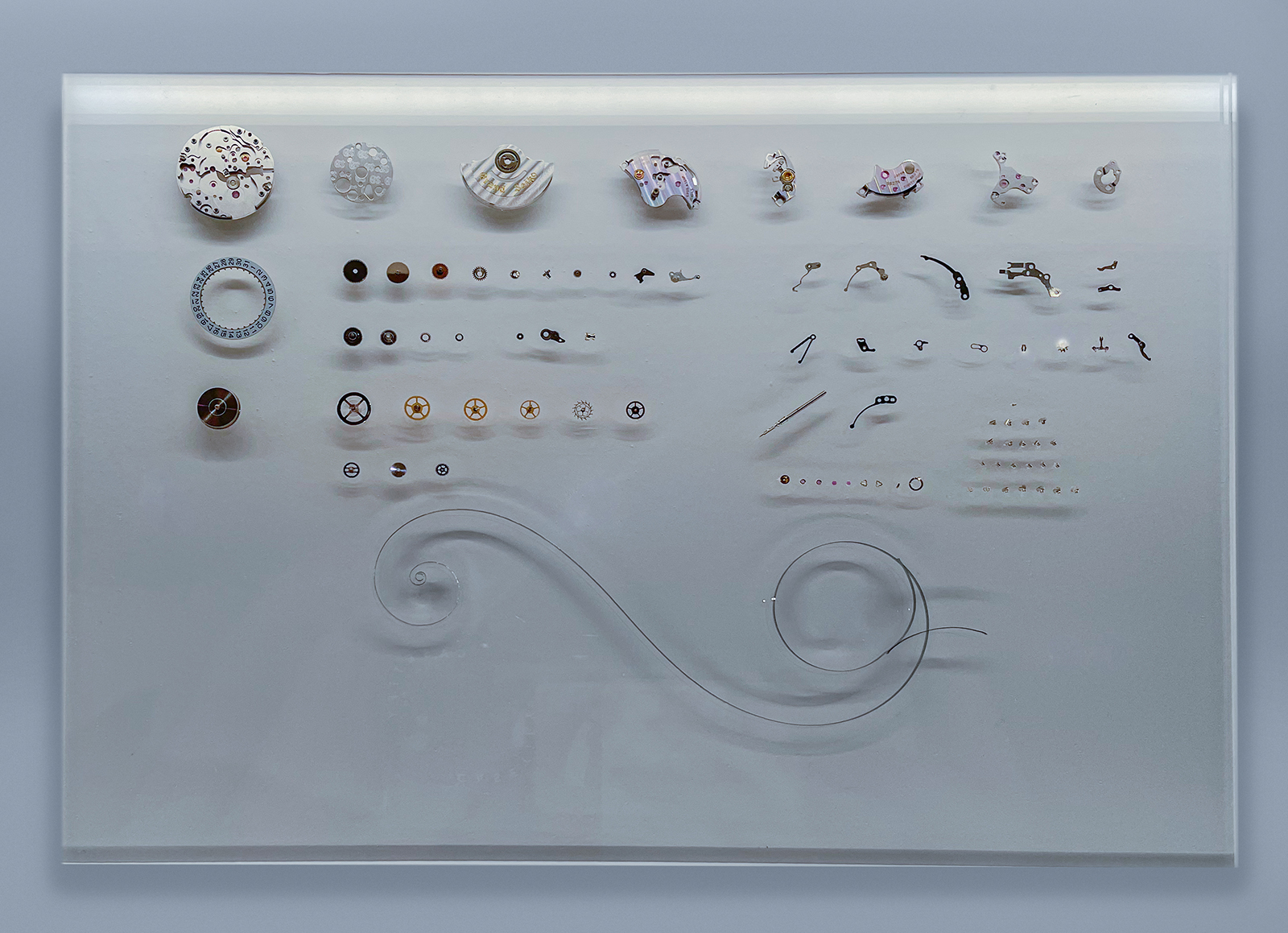

There were showcases featuring archival milestones and watches, deconstructed movements, specialised tools, materials, explanations of manufacturing technology and finishing processes.

Among these exhibits was a dedicated display highlighting the watchmakers who have achieved “Meister” certification, a formalised internal ranking system that Seiko uses to honor its most accomplished assemblers, adjustment watchmakers, engineers, designers, operators and artisans. It is divided into Bronze, Silver, and Gold Meister levels, each representing a progressively higher degree of mastery in their respective fields and are responsible for passing on skills to junior employees. Every 2 years, this ranking renews.

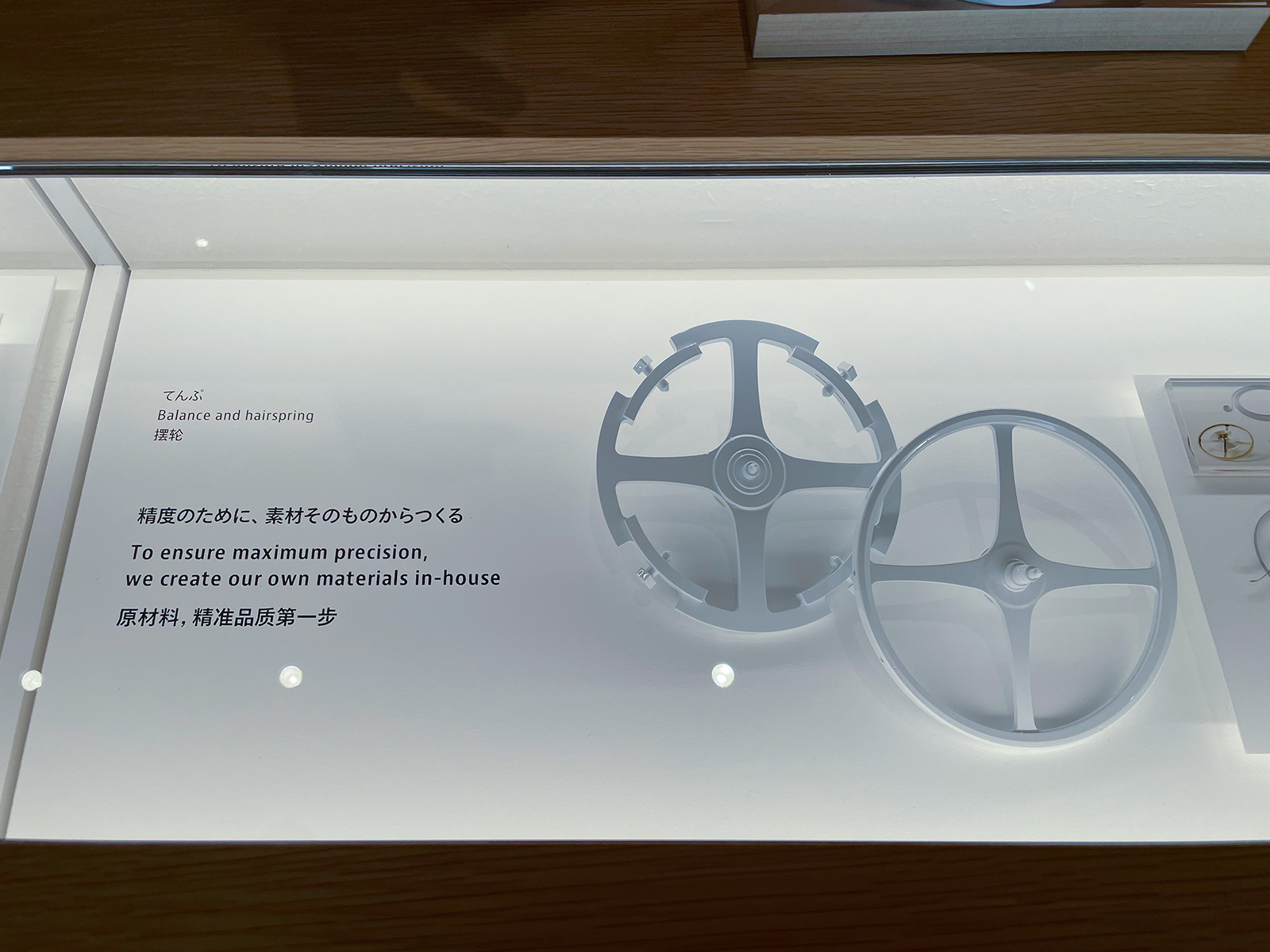

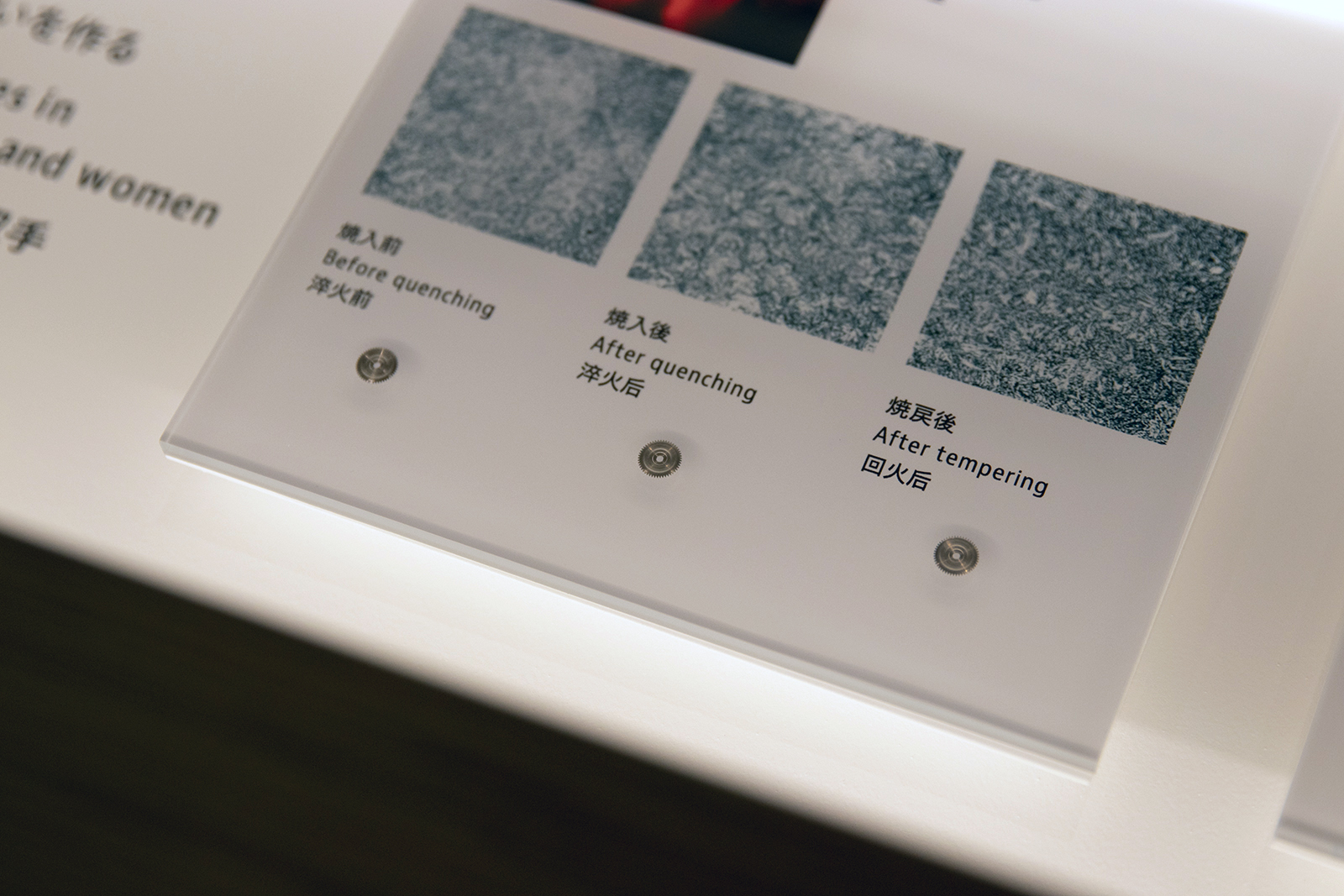

We were guided down the hallway to observe the entire assembly process in a clean room, which is organised row by row to follow the sequence of watchmaking. The first row is dedicated to preparing components for assembly, followed by the initial assembly, where parts are brought together to form the movement in its general production state. Further down, the hairspring and balance assembly are adjusted.

In the later rows, completed movements are placed in boxes and undergo a 17-day period of testing across three temperatures and in six positions, including the crown right position. Mr. Kubo explained that this position is particularly relevant in Japan, where it is common for people to place their watches on a table and use them as a desk clock. The Tentagraph undergoes an additional three more days of testing in an additional three positions with the chronograph running.

Once a movement meets Grand Seiko’s accuracy standards, it proceeds to casing, where the dial is affixed, hands are installed, and the movement is secured within the case. Before a watch is approved for final inspection, it must pass a three-step water resistance test. First, an air pressure test checks for case integrity. Next, the watch is submerged in water under controlled pressure to confirm resistance. Finally, a condensation test is performed by placing the case on a hotplate and applying a drop of water to the crystal to check for any internal moisture leaks. After clearing these tests, bracelets and straps are attached and the watches are ready for delivery.

On the second floor of the manufacture, there is lounge with a view of Mt Iwate. Here, visitors can handle and try on watches made in the studio, and this is where the exclusive Studio Shizukuishi limited edition SBGH283 is available for purchase.

Our tour concluded with an in-depth presentation of the new 9SA4 movement by its designer, Yuya Tanaka, as well as a live assembly demonstration by Hiroomi Suzuki. They shared that Grand Seiko approaches movement design with a focus on achieving precision, a long power reserve, and beautiful design. Arguably, it went beyond this with the 9SA4 which offers an unusually tactile and utterly indulgent winding experience, made possible with a winding click shaped like a wagtail, a bird of special significance to Morioka.

Right beneath the barrels, there are eight visible jewels that house the axles of the differential gear train that drives the power reserve indicator. It was astonishing to see Mr. Suzuki place a single bridge over 12 axles in a single step, as every pivot had to align perfectly with its jewel at the same time.

A hand-wound, high-frequency movement with an 80-hour power reserve is already a rarity, but one that exhibits this much care and attention to detail – mechanically, aesthetically and experientially – at this price point is virtually unheard of. Not long after that trip, I kept returning to that feeling – the weight of the crown between my fingers, the measured resistance, the way each wind brought the movement to life, accompanied by that deeply satisfying click. The SLGW003 had left an impression that just wouldn’t fade, and so I made the only decision that made sense. I bought it. The visit and the watch didn’t just deepen my appreciation for Grand Seiko but made it clear why, more than any other brand, this one feels like home.

Grand Seiko