Blancpain

Understanding the Chinese Calendar

For a taste of these so-called Rat watches, read our story here.

Besides, even though the Chinese calendar has been replaced by the Gregorian calendar for official/formal matters (even in China), it remains the go-to authority among the Chinese when it comes to festivals, holidays, and birthdays. And with the Chinese Almanac in hand, the calendar takes on even greater significance, holding the very keys of prosperity, status and longevity in designating the most auspicious days for all manner of life’s activities, from starting a business, getting married, traveling, renovating one’s home, getting into a contract, burying the dead, etc. Indeed, if we were marionettes with our destinies and heartstrings knotted to the cosmos, it’s not far fetched to think of the Chinese calendar as the quinary key to unlocking the Chinese psyche, determining what is/ought and foretelling what must be.

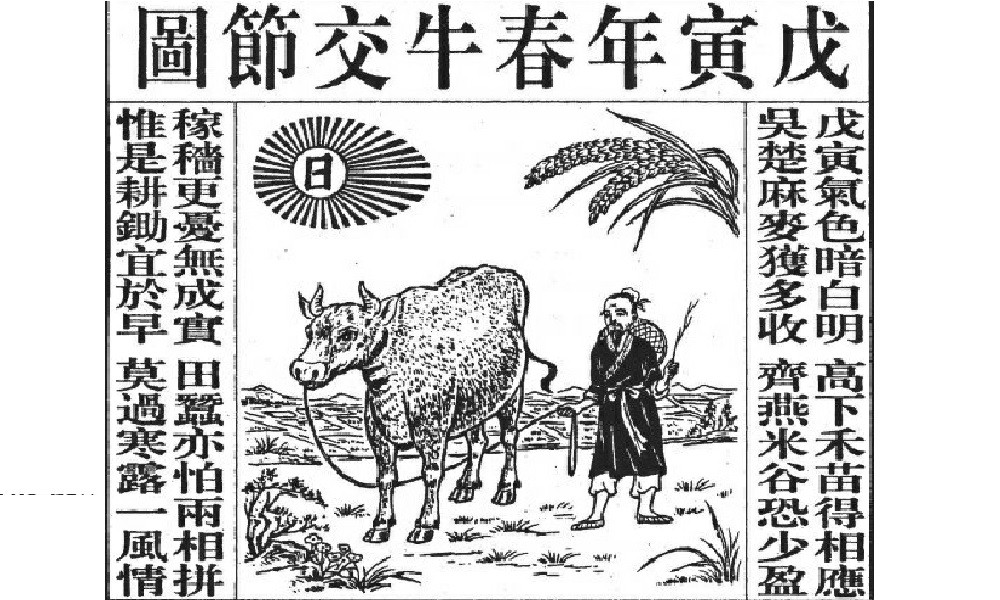

The Chinese Almanac, or the Tung Shu -- ‘The Book of Many Things’

Giants in the Field

Our ancestors are not without savage habits and this applies quite generally across all ethnicities. But when the ancients roll back their sleeves to create calendars like their lives depended on it (and it did), we wonder if they didn’t have help from galaxy-hopping space aliens: such is the extreme complexity of these creations — the mathematics and acute observation of the heavens — that many of our 21st century heads would burst if we try too hard to fathom their intricacies. The following then, is a brief, general guide to the Chinese calendar, without tripping headlong into a bottomless headache of astrology and the arcane arts of the occult.

Observation First

A now-forgotten movie (Patricia Arquette is in it) opens with a shot of an unspecified highway through the windscreen of a speeding car. It’s just black tarmac caught in the headlights, with lane markings flashing by to the beat of a drummy soundtrack. Watching the skies is a much quieter affair, but the same sense of not knowing where we are, pervades. Night and Day is straightforward enough. But where do we go from here? How many days and nights to make… what? Calendar information that we take for granted today is not intuitive at all. There aren’t labels marking the months as there would be signposts planted along a road. Yet, not knowing where we are in the apparent continuum of days, we are handicapped in forward planning, for life-changing activities like… agriculture.

A page from a Chinese calendar with a plethora of information snippets from the Almanac.

On these observations, the Chinese calendar has been in use, in various versions, revisions and by regional cultures (Vietnam, Korea, and in Japan until it was banned in 1873 during the Westward-looking Meiji Restoration) since between 8th and 5th century BC. Like the Gregorian calendar, the months alternate in number of days, but instead of adding a single day in February on leap years, the Chinese calendar is adjusted by adding a 13th month added to the end of the year. Different folks, different strokes.

Reading it: Zodiac Animals Come to Play

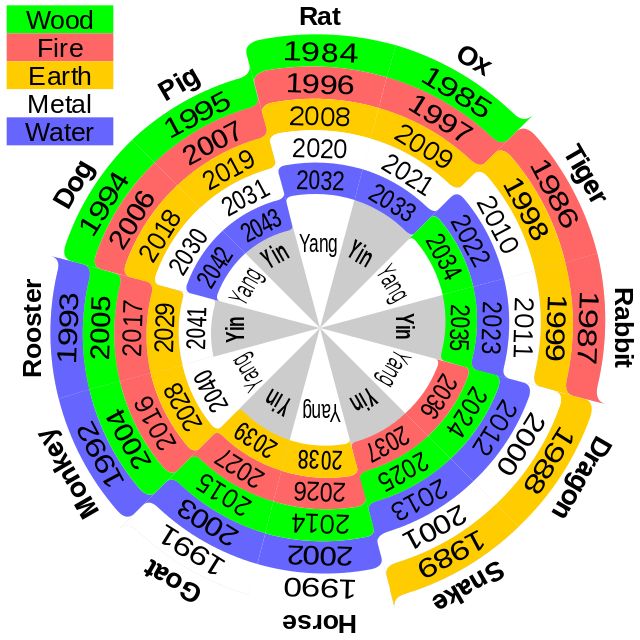

Why did we describe the Chinese calendar at the start as a quinary code? Because there are at least five components in the designation of each year, and instead of a serial number that runs into perpetuity, the names for the years run to 60 and are then recycled, making it a Sexagenary calendar. Counting from 2637 BC when the mythical Emperor Huangdi (the “Yellow Emperor”) supposedly invented the Chinese calendar, we are currently in the 78th 60-year cycle which began in 1984.

Think of each year as a word composed of five variables used in a cycle, say “C-R-A-Z-Y”:

C: One of 10 Celestial Stems

R: One of 12 Terrestrial Branches

A: Each sequential pair of Celestial Stem (C) corresponds to one of the Five Elements*

Z: Each year alternates in sequence as Ying or Yang

Y: One of 12 animals of the zodia, starting with Rat and ending with Pig.

* Five Elements: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water

This is well illustrated in the colour wheel which lists the corresponding Gregorian Calendar years: