Feature

Understanding Métiers d’Arts: Engraving

Feature

Understanding Métiers d’Arts: Engraving

The mechanical watchmaking renaissance saw a resurgence in the decorative arts known as Métiers d’Arts. Manual decoration, including angling and chamfering on movements, experienced a revival alongside artistic crafts like marquetry, enameling, guilloché and gem-setting. This revival in craftsmanship aligns with the growing demand for differentiated and more wholly engaging timepieces, ones that display not just fine mechanics but also exceptional aesthetics. In this section, we delve into four primary branches of expertise — guilloché, marquetry, engraving and enameling — and uncover the unique considerations and challenges that define these intricate crafts. Today we explore the art of marquetry.

ENGRAVING: The Art of Depth

In contemporary watchmaking, engraving has attained a prominent position among decoration techniques, securing its esteemed status as a métier d’art. Naturally, it evokes awe and amazement among collectors, as evidenced by notable examples such as the engraved balance cock of A. Lange & Söhne and the classical dial of Naoya Hida & Co. Its image in watchmaking is delicate, and its standing highly regarded, making it challenging to grasp that the art of engraving may be the oldest among the five métiers d’art techniques covered in our special feature. Engraving’s historical roots exte nd back to the Stone Age, where cave dwellers left their marks for us to discover, evident in symbolic images carved into stone walls or even stone tools.

The art of engraving has traversed a vast journey over the past several millennia, eventually finding its place in watchmaking, a field with a considerably shorter history by comparison. It is fascinating to realize that such an ancient technique now adorns watches — not only enhancing their aesthetic appeal, but also providing a profound sense of culture and history. This is the focus of our discussion today as we delve into the captivating world of engraving, exploring its process, the tools involved, and the accomplished engravers of our time.

PROCESSES AND TOOLS

As with most art forms, the fascination with engraving prompts enthusiasts to seek out various examples and discern the most beautiful pieces for their collections. The journey of delving into the beauty of this craft inevitably sparks curiosity about the techniques behind creating these pieces. The process of engraving begins not with the dial blank, but sketches on paper which range from simple lettering to the reproduction of renowned paintings. The planning phase holds particular significance, especially for crafting exquisite, one-of-a-kind dials. Once the design is conceptualized, it is transferred onto the dial. The methods of transferring the design vary. One traditional approach involves free-hand work, where the engraver scratches the surface of the dial to create a shallow outline that guides the subsequent engraving work. This might include drawing onto a piece with a pencil and then scratching using a pointed burnisher, and this preparation technique is known as drypoint.

The one-off Patek Philippe "Way of the Bow" pocket watch with a hand-engraved and hand-guillochéd dial, all cloaked in translucent ename

Another popular method is using a printed drawing on paper placed on the metal (printed side down). Rubbing with a cotton swab soaked in acetone transfers the design. Once the paper dries off, it should leave the printed ink on the metal. To secure that ink and make it durable, the engraver will heat it using a heat gun, fixing the toner on the metal. Additionally, transferring a pattern from an already engraved template is possible. This method involves applying rubbing wax to the engraved template and wiping off the surface to eliminate any excess, ensuring that the wax remains only in the engraved grooves. Subsequently, a piece of clear tape, with its sticky side facing down, is firmly pressed onto the template to capture the intricate wax design. The final step involves pressing the tape onto the dial blank slated for engraving. With a pointed burnisher, the wax adheres seamlessly to the piece, ensuring a refined outcome once the tape is delicately removed.

Drafting the pattern to be engraved (Image: Vacheron Constantin)

Alternatively, contemporary methods such as laser pre-engraving are frequently utilized for text engraving in series, providing both precision and efficiency. As we’ll explain later based on an interview with a master engraver, incorporating laser techniques is not considered sacrilegious to the traditional art of engraving. Another method involves applying indexes or engraved decorations using stamps. Both laser and stamping methods ensure accuracy and save time, especially when dealing with the intricate geometric designs of a brand’s logo. The engraving process does not adhere to strict rules; instead, multiple techniques are available. In certain instances, the engraver might opt to skip transfers altogether and directly engrave into the dial blank, employing freehand engraving for a more personalized touch.

Despite the numerous methods available, master engravers like Artur Akmaev rarely use freehand techniques when working on watch parts or dials. Mr. Akmaev explains that this is because having at least major elements prepositioned on the piece is crucial. Mistakes involving size or placement, especially for large elements, are easily made and can significantly affect the overall proportion. Additionally, corrections are challenging once the engraving is complete. Further emphasizing the difficulty, Akmaev highlights the limited field of view when working under a microscope. This makes it hard to visualize the entire design and ensure accurate proportions for larger elements. Losing sight of an element within the limited view can easily lead to errors that compromise the entire composition.

Mr. Akmaev’s engravings demonstrate high quality and precision, as evident in the videos posted on his Instagram page. Therefore, we are interested in his personal experience and practices when it comes to transferring an image onto a dial blank. Mr. Akmaev revealed that he personally does all his designing on a vector graphics software and uses a fiber laser engraver to make the outlines, creating direction lines that help him in the engraving process. This very faint outline can be seen in the video, but it still takes him takes several additional cuts to turn the basic laser-engraved outline into lines with the appropriate depth and width.

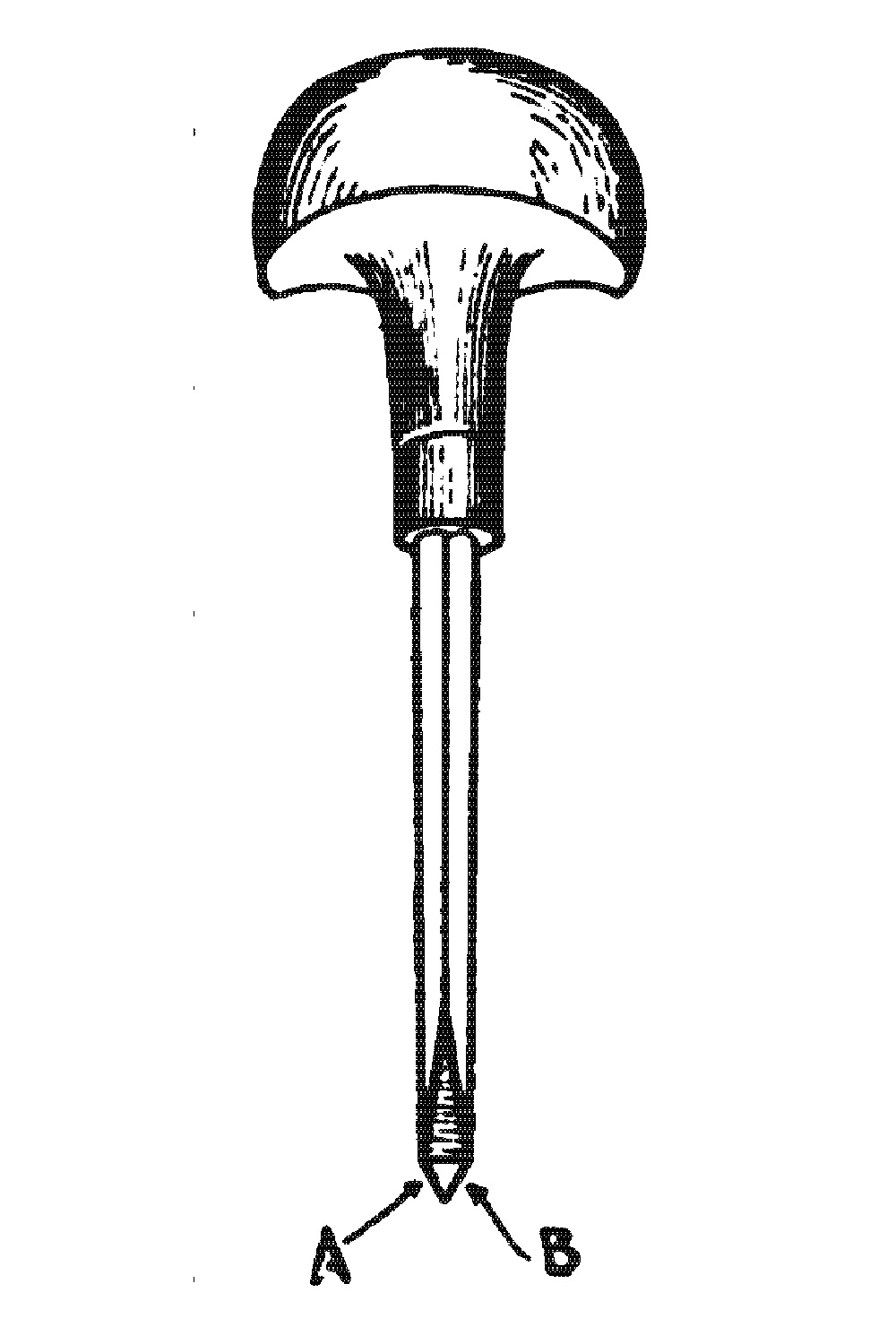

After transferring the design outline onto the dial, the engraver begins the process of excising materials from the dial while also refining the engraved surface. This can be a complex procedure necessitating various tools. A burin or graver is the primary tool used for removing metal from the dial, consisting of a long, thin steel pointer affixed to a round knob for handling. Interestingly, the metal pointer does not have a cone-shaped tip; instead, it is multifaceted. The front of the tip features a diamondshaped flat surface angled at 45 degrees, with the bottom or heel of the surface being sharp and pointing outward. Only the bottom of the surface is utilized for engraving, and it incorporates a clever design with a bevel at the heel to create a flat surface, which is typically about half a millimeter. This allows it to glide along the metal dial smoothly, preventing it from getting stuck during the engraving process.

The process of engraving involves the use of a burin angled at 45 degrees. (Images: Vacheron Constantin)

As the tip dances across the dial, it leaves behind v-shaped grooves, creating facets that play with light and shadow. It’s this dimensionality that sets engraved markers apart from their flat, printed counterparts, and even the depth of applied markers. Watch-dial engraving, akin to calligraphy, relies on meticulous control. The graver’s path must be carefully planned, carving clean lines and seamless junctions. Every cut, like a sculptor’s chisel, shapes the metal, forming light-catching grooves and subtle shadows. Every minute detail, from the width of the line to the sculpted depths of the groove, contributes to the final artwork. It is indeed an intense hand-eye coordination exercise, as the engraver pushes the graver while simultaneously rotating the dial (fixed onto a rotating base).

The process of engraving involves the use of a burin angled at 45 degrees. (Images: Vacheron Constantin)

Another indispensable member of the engraver’s toolkit is the scraper. As the graver carves its lines into the dial’s surface, it inevitably leave behind tiny strips of metal called burrs. These slivers have to be carefully removed from the dial’s surface, and that is when the scraper comes in. Modern-day engravers are fortunate in that they no longer need to craft their own tools. Indeed, it is no longer advisable to handcraft tools, as factory production proves to be more cost-effective and accurate, particularly in terms of controlling the quality of steel and the tempering process. Nevertheless, engravers are still responsible for sharpening their gravers. The sharpening and polishing of the graver constitute a crucial step, requiring tools such as a bench stone (coarse and fine), a fine ruby stone, a loupe, a steel rod, and a copper plate for testing the sharpened graver. It is essential to sharpen both the tip and the heel of the graver. If the heel is not sharpened properly, it may impede smooth movement, leading to skittering or even tearing the metal through to the other side. Modern technology also plays a role in sharpening gravers. Tools like fixtures with adjustable angles allow precise placement against polishing stones. Even more specialized options like the GRS Apex fixture, designed for use with polishing lathes or rotary sharpening wheels, offer additional control and accuracy.

TYPES OF ENGRAVING

While many may associate engraving primarily with the balance cocks of Lange watches, this art form offers a vast array of possibilities for dials and cases by employing different engraving techniques.

A two-tone Naoya Hida & Co. Type1D featuring its signature dial with handengraved Breguet numerals

STANDARD ENGRAVING

Let’s start with the most common technique, standard engraving, which involves carving directly into the metal surface to create a subtle yet enduring impression. Picture delicate lines forming crisp lettering, precise markers and intricate floral motifs — all producing a beautiful negative relief effect. This versatile technique caters to a wide range of designs, making it a popular choice among watchmakers. However, standard engraving is not a monolithic entity; within this category lies a spectrum of skills and styles. Technical engraving, characterized by its cleanliness, precision and efficiency, focuses on clarity and legibility Numbers, letters and other straightforward elements fall under this banner, demanding impeccable execution in terms of line thickness, spacing and overall cleanliness. It’s akin to executive calligraphy for metal, conveying professionalism and precision.

The intricately hand-engraved Vacheron Constantin Copernicus Celestial Sphere

On the other hand, modeled engraving places artistry at the forefront. Skilled hands transform metal into miniature sculptures, capturing the essence and realism of elements such as leaves, textures, or even figures. This is where artistic freedom flourishes, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible on such a small canvas. Crucially, the standard engraving technique serves as the foundation for various other engravings, including relief engraving (as we’ll explore later) and mixed methods.

RELIEF ENGRAVING

Also known as bas-relief engraving, relief engraving is considered more painstaking and complex than standard engraving — and rightfully so. This type of engraving creates patterns or lettering that are raised from a flat background. The process unfolds in two steps. Initially, it mirrors standard engraving, where the outline of an object is carved into the dial. In the second step, everything outside the hand-engraved outline is removed. This process begins by outlining the design using a V-cut graver tilted toward the side of the relief, creating an angled cut with one side vertical and the other flat. Subsequently, flat gravers of varying widths carefully eliminate the excess material, shaping the raised elements. This demands painstaking control and precision, resulting in impressive depth and dimensionality to the dial.

The richly detailed engraving on the Vacheron Constantin Les Cabinotiers Grand Complication Phoenix;

While master engraver Yasmina Anti acknowledges that machines like CNCs can assist in removing excess material in preparation for hand-finishing, she emphasizes the importance of preserving the human touch in true basrelief engraving. For her, introducing machines to execute the design itself diminishes the essence of “handmade” and reduces it to mere “hand-finished”.

Ms. Anti highlights the near-perfect mimicry achievable by advanced machines like five-axis CNCs and 3D production. However, she passionately argues that the soul of the art lies in the subtle nuances, textures and individual expression that only human hands can imbue. This concern reflects a broader trend of machines encroaching on traditional crafts, particularly in recent years. While acknowledging the impressive technical accuracy of machine-made pieces, Ms. Anti worries about the potential loss of the emotion and personality inherent in handcrafted creations.

LINE ENGRAVING

Line engraving is as much a compositional technique as it is an engraving technique, involving the creation of graphic images using multiple thin lines of varying depths and widths. By manipulating the spacing and density of these lines, artists can even create the illusion of shading. After engraving the lines, the surface is flattened by sanding it with fine files or sandpaper. In some cases, the line grooves are filled with ink or paint to enhance the clarity of the lines.

The Patek Philippe Ref. 20141M-001 "Japanese Stamps" with an engraved center filled with translucent enamel

HAMMERING AND STIPPLING

Hammering and stippling techniques are often used to create a surface with many tiny spots that shimmer, whether on a dial, movement plate or case. This is sometimes known as the frosted finish. Hammering is done using both a graver and a hammer, with the hand holding the hammer striking the back of the graver, leaving tiny spots on the metal surface to be engraved. Meanwhile, stippling involves digging into the surface using the graver without a hammer. Depending on the desired texture, other tools such as stones, brushes and cutters may be used. In some cases, the graver may even be attached to a pneumatic graver, which relies on air pressure to power the engraving tool.

The "dragon-scale" dial of the Simon Brette Chronomètre Artisans Souscription engraved by Yasmina Anti

SCULPTING

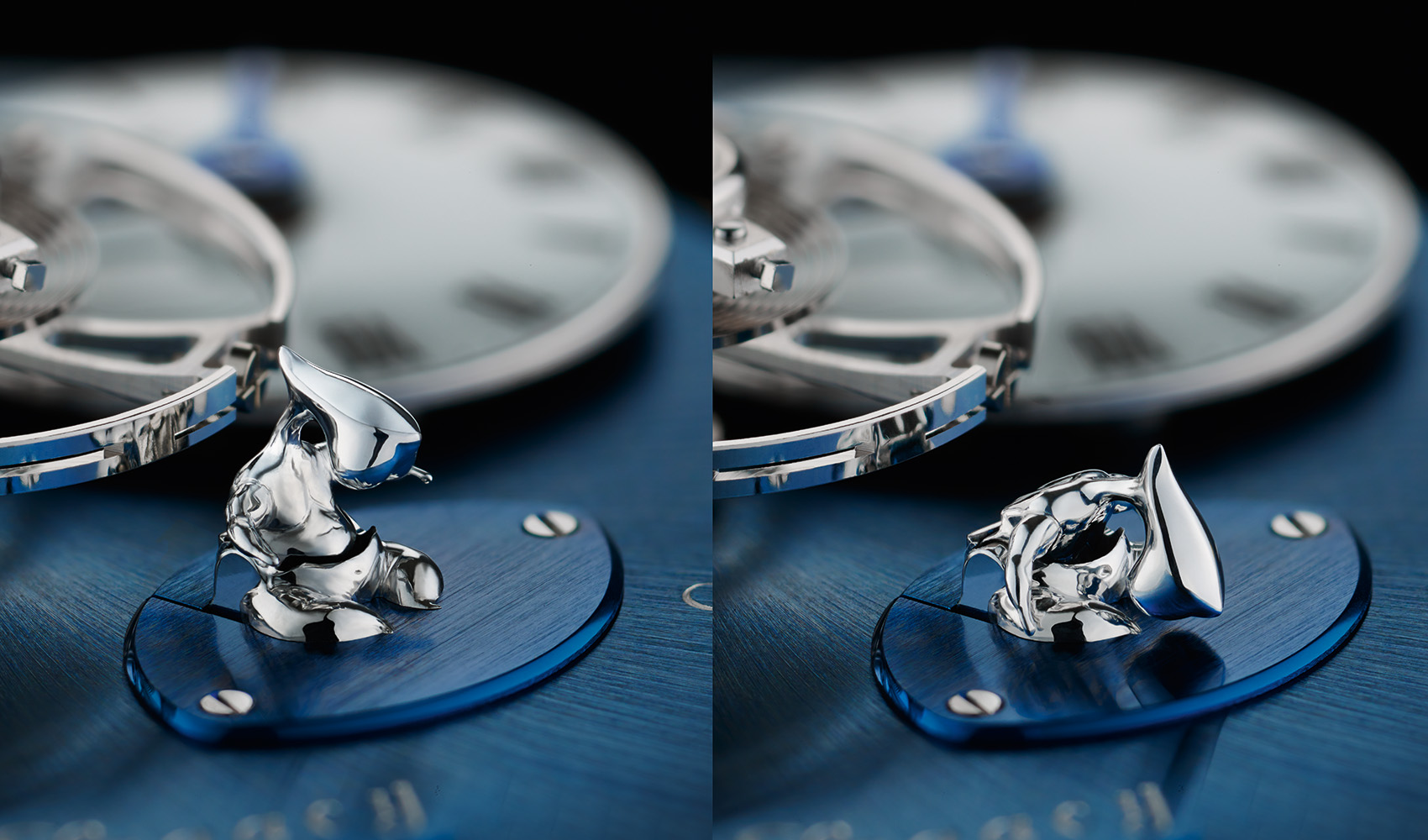

Although less commonly seen in watches due to their size, sculpting is perhaps the most challenging type of engraving because it is three-dimensional. Unlike removing metal from a flat surface, sculpting involves removing material from a block to create a 3D object. These objects are then fixed onto a dial to add visual depth that cannot be achieved through traditional engraving. Examples include the MB&F LM1 Xia Hang, as well as many of the dragon-themed métiers d’art watches.

The MB&F LM1 Xia Hang incorporates a sculpted alien that bows to indicate the power reserve

COMBINING TECHNIQUES

It’s also common for an engraved dial with a good amount of detail to showcase a combination of different engraving techniques. Take, for example, the De Bethune Maestri’Art I, which features both raised and sunken surfaces on the dial. The dragon is achieved via relief engraving, while the cloud pattern is created using standard engraving techniques. Additionally, there are finishing and inlay techniques used to add color — the black dial itself was created by De Bethune’s resident metallurgist, Denis Flageollet, while the gilt part was inlaid with gold wire.

The De Bethune Maestri Art I features a dial and case back elaborately engraved by Michèle Rothen Rebetez

MODERN TECHNOLOGY

In addition to pneumatic engravers, modern technology offers advanced methods of engraving that eliminate the need for a human touch, such as five-axis CNC machines and lasers. Distinguishing between machine and hand engraving can be challenging, particularly for typical engravings of text and numbers that prioritize precision over artistic expression. Mr. Akmaer offers a tip for differentiation: examine how corners, or the lowest points where two or three facets meet, align. If all corners meet at the same angle with identical precision, it is likely machine-engraved. While it is possible for hand engraving to achieve perfection, if every number appears identically flawless, it does raise suspicion.

GREAT ENGRAVERS OF OUR TIME

The individuals or organizations who passionately practice the art of engraving in watchmaking can be loosely categorized into three groups. The first group, dial-making specialists, is best represented by Oliver Vaucher, a workshop based in Geneva that supplies both big brands and small independent watchmakers. Some of the more prominent engravers of today also got their start at this specialist, such as Hannelore Lass, who works on her husband Christian Lass’s watches. The second group comprises the more prominent haute horlogerie brands with their in-house métiers d’art workshops. These most notably include Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe, which produce annual collections of objets d’art that often involve fine engraving. It’s also no surprise that major watchmakers who also produce high jewelry, such as Piaget and Cartier, also have engravers in-house.

The Longines Master Collection 190th Anniversary presents a value-proposition dial with Breguet numerals deeply engraved via laser

Some watchmakers do engraving not so much as a métiers d’art decoration, but to decorate the functional part of a watch. For example, Greubel Forsey is known for its frosted movement plate finish; Akrivia, its hammered movement plate; Roger Smith, its hand-engraved dial and movement; and Moritz Grossmann and Lange, their floral engraving on the movement balance cock. Finally, there are independent engravers who partner with a variety of brands to produce unique and striking artwork. Some of the best include Michèle Rothen Rebetez, Eddy Jaquet, Yasmina Anti, Artur Akmaev, Christian Thibert, Dick Steenman and Keiji Kanagawa. As is expected, these practitioners come from all over the world, since engraving is a very old art practiced in all cultures.

The Louis Vuitton Tambour Carpe Diem features an elaborately engraved sculpture of a skull and a snake coiled around it. The body of the snake is enameled by Anita Porchet while all the engraving is done by Dick Steelman

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF ENGRAVING

It’s unnecessary to reiterate how beautiful or luxurious a dial can appear when engraved, lending it unmatched visual depth. However, the beauty of the art of engraving itself, in terms of its practice, cannot be overstressed. Concerning métiers d’art watch dials, the various types of artisanal decorations can roughly be classified into two categories. The first category comprises those that demand highly precise execution, prioritizing perfection in technique above everything else. Examples include guilloche and marquetry, which require utmost precision in cutting. The second category includes designs that also demand great technique but prioritize creative expression in art, such as enameling, particularly miniature enamel painting.

That said, there’s always something that falls between these two categories, and that’s precisely where engraving fits. It demands precision, and perhaps even some repetitive work, such as creating the outline on a dial before beginning the actual engraving process. But more importantly, it requires artisans to maneuver the graver through the dial to transform the outline into three-dimensional grooves with varying depth and thickness – strokes that come to life and dance on the dial, in other words. Therefore, the art of engraving is a beautiful practice that brings out the best in humanity – its diligence and creativity – something that cannot be fully replaced by a machine, however precise it may be.