News

Understanding Métiers d’Arts: Marquetry

News

Understanding Métiers d’Arts: Marquetry

The mechanical watchmaking renaissance saw a resurgence in the decorative arts known as Métiers d’Arts. Manual decoration, including angling and chamfering on movements, experienced a revival alongside artistic crafts like engraving, enameling, guilloché and gem-setting. This revival in craftsmanship aligns with the growing demand for differentiated and more wholly engaging timepieces, ones that display not just fine mechanics but also exceptional aesthetics. In this section, we delve into four primary branches of expertise — guilloché, marquetry, engraving and enameling — and uncover the unique considerations and challenges that define these intricate crafts. Today we explore the art of marquetry.

MARQUETRY: The Art of Illusion

Among the decorative arts in watchmaking, such as enamelling and engine-turning, there is an even more exotic craft known as miniature marquetry. Unlike its counterparts, marquetry is a craft that is only practised by a handful of independent artisans. It involves the intricate arrangement and inlay of tiny, precisely cut pieces of veneer, leather or other materials to create detailed designs on a flush surface.

Marquetry originated from the ancient art of inlay that dates back several millennia in Egyptian, Greek and Roman civilizations. As opposed to marquetry which involves thin slices of materials that are cut and assembled on a supportive surface, inlay involves carving a recess into a surface and embedding a second material into it. This craft experienced various forms of revival throughout history, notably during the Italian Renaissance in the 15th century where it was adapted into a practice known as “intarsia.” It involved the cutting, shaping and arrangement of blocks or sections of wood to create the illusion of depth, achieving a more substantial effect through the deliberate incorporation of different levels and contours. As such, the practitioners of intarsia, or intarsiatori, were known as masters of perspective. The technique was used to embellish both secular and religious objects, creating luxurious and convincingly three-dimensional designs.

Despite acclaim from some quarters, the Florentine polymath Giorgio Vasari, often regarded as the first art historian, famously dismissed intarsia as an “imitation of painting” and something that merely “required more patience than skill.” But unlike painting, which involves applying pigments to a flat surface, intarsia and marquetry demand meticulous cutting and fitting of various wood elements to create a cohesive and detailed composition. The artist must navigate the inherent characteristics of wood, such as grain patterns and colors, as well as master woodworking techniques.

Techniques in wood marquetry became far more sophisticated in Flanders in the 16th and 17th centuries. One development that would revolutionize the intricacy achievable in marquetry work was the invention of the fretsaw. It featured a thin steel wire held taut, incorporating carefully filed teeth that could cut complex curved shapes. By the latter half of the 17th century, France had become the richest country in Europe and marquetry reached its height, notably through the influential work of André- Charles Boulle.

Widely regarded as one of the greatest marqueteurs in history, Boulle served as a cabinetmaker to King Louis XIV and was celebrated for developing the technique of marquetry into a fine art. Boulle’s innovation, often termed “Boulle work,” involved the incorporation of wood, tortoiseshell and metal, often copper, bronze, brass or pewter into elaborate arabesque and intricately foliate designs. Boulle’s inventive approach extended beyond materials, encompassing a unique layering technique. Contrasting sheets of veneer were meticulously stacked into blocks, which were then cut with a fretsaw, resulting in two distinct sheets boasting contrasting patterns. Beyond furniture, his work also extended to the embellishment of clock cases and other timekeeping instruments such as barometers.

In the 20th century, the art of marquetry, like many other decorative arts, was partially lost as mass production and modern design trends continued to influence the market for handcrafted goods. However, the latter half of the century witnessed a resurgence of the appreciation in traditional craftsmanship, driven by the desire for uniqueness and cultural value. Artists and designers explored new ways to incorporate marquetry into modern contexts. In the realm of horology, particularly watchmaking, the art of miniature marquetry found a niche. Watch dials became canvases on which tiny, precisely cut pieces of materials are delicately arranged to create intricate and captivating designs that transcend the utilitarian function of timekeeping, transforming each watch into a wearable work of art. While technological advancement, such as the use of laser technology, has significantly propelled the evolution of marquetry at large by enabling the cutting of tiny pieces of veneer with unprecedented precision, the intrinsic value of marquetry lies predominantly in the meticulous human craftsmanship lavished in its creation. Like various other forms of decoration where modern technology has eclipsed human hands, it is still the skill, dedication and artistry of the craftspeople that continue to imbue the craft with meaning.

WOOD MARQUETEURS AND MASTERPIECES

The introduction of marquetry in pocket and wristwatches occurred relatively recently. What has now become one of the most coveted forms of decoration among collectors emerged almost serendipitously. Initially, Patek Philippe had commissioned a marqueteur to create a special presentation box for a client. Impressed with the outcome, Patek Philippe then encouraged the craftsman to apply the artistry on a miniature scale, leading him to craft a dial for a pocket watch. He then created the first example of a watch dial decorated with wood marquetry — the Black Crowned Cranes of Kenya pocket watch, ref. 982/115, in 2008. This was followed by the Royal Tiger wristwatch, ref. 5077P, two years later. That craftsman was none other than Jérôme Boutteçon, an award-winning marqueteur who worked for Philippe Monti, a company that specializes in the production of caskets, music and cigar boxes in Sainte-Croix. Soon the rest of the watch world caught on, with brands like Cartier and Jaeger-LeCoultre commissioning his services to decorate their dials as part of a broader effort to revive métiers d’arts from the brink of extinction.

Contrary to Vasari’s criticisms of intarsia as counterfeit painting, it is precisely the naturalistic, painting-like quality of Boutteçon’s marquetry that makes it truly remarkable. Among some of his most outstanding creations is the Patek Philippe ref. 995/107G “Portrait of an American Indian,” created for the Grand Exhibition in New York in 2017. The dial showcases the visage of a Native American chieftain in full regalia, meticulously executed in marquetry. The process demanded the precise cutting and placement of 304 tiny shards and 60 different inlay cuts sourced from 20 types of wood. In his latest endeavors, he pushed the boundaries even further. The ref. 995/131G-001 “Portrait of a Samurai,” created for the Grand Exhibition in Japan last year, stands as his most complex dial to date. This piece vividly portrays a samurai in armor using an astounding 1,000 pieces of wood, carefully chosen from 53 different species.

Patek Philippe Ref. 995/137J-001 “Leopard"

Another noteworthy creation is the ref. 995/137J-001 “Leopard,” a masterpiece executed in enamel and marquetry, depicting a majestic big cat emerging from the darkness. The leopard comes to life through the assembly of 363 tiny veneer parts and 50 inlays, spanning a palette of 21 species of wood with diverse colors, textures and veining.

Another independent artisan that specializes in wood marquetry today is Bastien Chevalier, who honed his craft under Jérôme Boutteçon and has been working independently in Sainte-Crox for the last 17 years. His work initially began with musical boxes for the esteemed automaton maker François Junod, and watch winder boxes for Vianney Halter. Subsequently, he delved into creating dials, lending his skill to brands such as Parmigiani, Vacheron Constantin, and more recently, Louis Erard. At the same time, he also founded MBCH in 2013, a watch brand that creates unique watches with marquetry dials designed by himself to the client’s request. Notably, his creations have a distinct modern aesthetic characterized by abstract motifs and bold lines, showcasing his contemporary approach to marquetry in watchmaking.

A striking example of Chevalier's craftsmanship, showcasing a dial adorned with a monkey skull meticulously crafted from 40 individual pieces

Recently, he completed one of his most intricate dials, featuring an abstract design commissioned by a client, which prominently showcases a monkey skull motif. The entire dial comprises of 120 pieces and nine species of wood, some tinted and some natural, requiring six weeks of work. The skull itself is a marvel, constructed from 40 individual components and measuring a mere 10mm by 12mm. “The greatest challenge lay in the interlacing of the upper portion,” he elaborates. “If the coloured parts are too small, there will be a joint and if they are too large, it shifts the entire composition, and the interlacing is not regular.”

THE PROCESS OF MINIATURE WOOD MARQUETRY

Marqueteurs have a dedicated storage area for their wood supplies, often a cellar. This space is designed to maintain optimal conditions, such as controlled humidity and temperature, to prevent warping, cracking or other undesirable changes in the wood. Prolonged exposure Left to right: A striking example of Chevalier’s craftsmanship, showcasing a dial adorned with a monkey skull meticulously crafted from 40 individual pieces; a MBCH timepiece featuring a marquetry dial depicting a bee, honeycomb and flowers to sunlight or artificial light can cause wood to undergo photochemical reactions, leading to color changes. Thus, proper storage ensures that the wood remains in good condition and retains its natural characteristics.

A marqueteur maintains a diverse inventory of wood species. This variety allows for greater creative flexibility and the ability to achieve a wide range of visual effects. Different woods have distinct colors, grain patterns and textures, and the marqueteur’s skill lies in harmoniously combining these species to bring the design to life. Chevalier, for instance, works with over 200 species of wood from Madagascar ebony, the darkest wood, to Madrona burr, the lightest. They are thinly sliced to create delicate sheets. “Personally, I like to mix natural woods with tinted wood because tinted is more stable over time in terms of their color, which allows the initial visual rendering to remain the same,” says Chevalier. Tinted wood is created using dyes which penetrate the wood and color it from within.

MBCH timepiece featuring a marquetry dial depicting a bee, honeycomb and flowers

Once the dial pattern is finalized and the wood is selected, depending on the level of complexity, the process starts with creating a line drawing on an enlarged scale on tracing paper using a Rotring Rapidograph pen with Indian ink. The purpose of this is to create an outline for each of the pieces present in the pattern. Subsequently, the drawing is digitally reduced to the required size and printed out on paper. The parts are then cut using a scalpel without touching the lines. The micro-sized paper cutouts are then strategically arranged on the selected veneers and glued using bone glue. These paper pieces act as guides for cutting the corresponding veneers. Then, the veneers are sawn using an electric saw blade which is operated by a switch, or a footoperated frame saw where the cutting action is powered by the marqueteur’s physical effort, specifically through a foot pedal that controls the up-and-down movement of the blade. While both methods involve manually guiding the veneers to cut the desired shape, the foot-operated frame saw demands a higher level of coordination, requiring synchronized movement of both hands and feet for precise and intricate cuts. Then, as the marqueteur meticulously maneuvers the veneers, the slender blade, measuring just 0.2mm in thickness, slices through the veneers with precision. The individual marquetry pieces are intricately assembled like a puzzle, and temporarily held together with scotch tape. The inner pieces are fitted and delicately hammered into the outer composition. Subsequently, the reverse side of the marquetry is glued onto kraft paper and the tinier pieces are then inlaid into the pattern. Upon securing the marquetry, the top side is glued to kraft paper. Then the reverse undergoes a cleaning process that involves sanding away the kraft paper and residual glue, followed by a sanding of the marquetry to achieve an even surface. It is then attached to the dial base using an adhesive. Finally, the top side is sanded and a protective layer of anti-UV varnish is applied over the dial.

BEYOND WOOD

Elsewhere, brands such as Hermès, Piaget, Harry Winston, Van Cleef & Arpels and Bulgari have gone beyond wood marquetry and begun incorporating an astonishing array of materials. In 2018, Hermès became the first to introduce leather marquetry in watchmaking. The process begins with the careful selection of high quality leather, where different textures and colors are considered to meet the aesthetic and structural requirements of the final design. They are then carefully thinned to about 0.5mm, before being cut to the required size and shape. One by one, the leather fragments are picked up with a tweezer and assembled and glued on the dial blank to form an animal motif.

Harry Winston, on the other hand, introduced feather marquetry to the world of watchmaking in 2012, showcasing dials adorned with vibrant purple and turquoise pheasant, silvered pheasant, and guinea fowl feathers. This intricate craft, often teetering on the brink of obscurity, found a lifeline through the dedication of a select group of passionate artisans. The sole artisan, or plumasserie as they are called, behind the majority of, if not all, feather marquetry dials in watchmaking is Parisian plumassière Nelly Saunier who has been practicing the craft for more than three decades.

Feather marquetry extends beyond the mere selection of feathers; it involves a deep understanding of the avian plumage’s characteristics, colors and textures. The feathers are ethically sourced and treated with the utmost care. The preparation phase involves a multistep process that includes washing the feathers with a gentle soap and water mixture to remove their natural protective coating. Following this, a chemical compound is applied to ensure the feathers are free from bacteria. The feathers then undergo tinting and treatment with sulfur before being laid out to dry. Once dried, the feathers are steamed individually to restore their original texture and softness. Only at this point does the transformation from raw material to artistic medium begin.

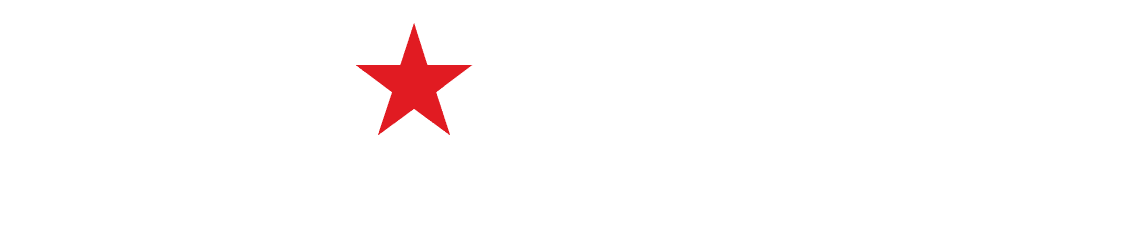

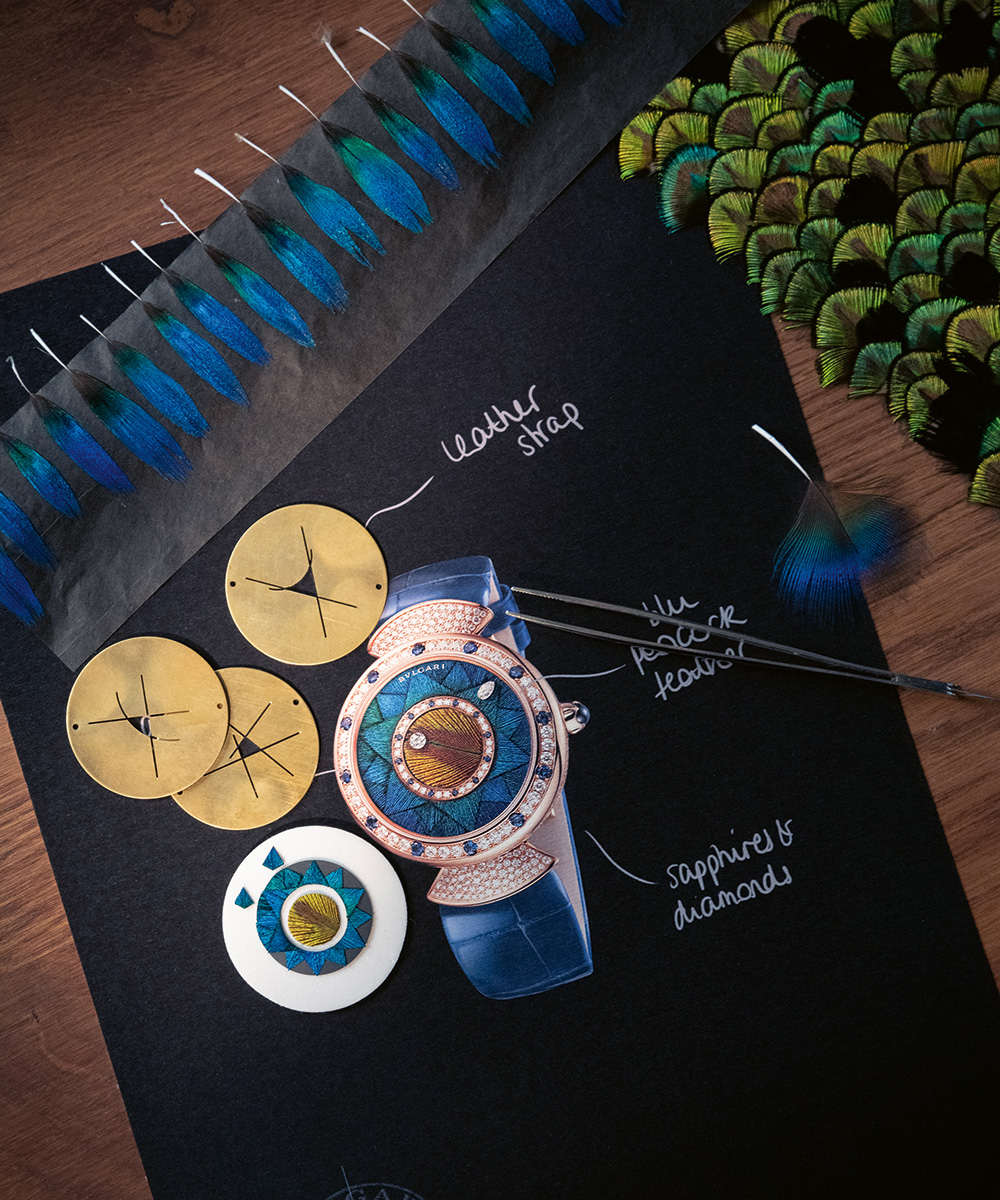

Among Nelly Saunier’s most outstanding work in recent years is the Bulgari Divas’ Dream Peacock Dischi launched in 2021. It features two nested rotating disks on the dial, artfully embellished with peacock feather marquetry. The inner disk replicates the mesmerizing eye of a peacock’s feather, while the outer ring boasts a dazzling geometric pattern in brilliant blue. This involved the assembly of approximately 500 individual feathers, each carefully chosen and matched based on their color and texture. The precision in matching is crucial as the feathers must seamlessly blend to create a cohesive and visually stunning effect. Any deviation in color or texture among adjacent feathers would be glaringly apparent and disrupt the overall harmony of the design.

The painstaking process of feather marquetry involves selecting, cleaning, pressing the feathers under small weights and cutting them into geometric shapes using a metal template

Following the selection, matching and washing process, the feathers are delicately pressed under small weights to ensure that they lie perfectly flat. The next steps involve the feathers being meticulously glued and cut into precise geometric shapes. To maintain uniformity across the entire dial, a purpose-designed metal template is employed. This template guarantees that each feather segment adheres to the designated shape and size, leaving no room for irregularities. The plumassière’s keen attention to detail during this stage is indispensable, as any rough edges or mis-sized portions would immediately stand out once the components are integrated into the overall design on the dial. Before they are assembled on the dial, they are pieced together on a mock-up where the intricate arrangement is finalized, ensuring a seamless blend of colors, textures and patterns.

While most dial marqueteurs tend to focus on and master one specific material, Rose Saneuil is distinguished by the astonishing variety of materials she skillfully handles and combines. This includes wood, leather, straws, motherof- pearl, stones, feathers, leaves, eggshells and even beetle elytra. After completing her training in cabinetmaking and marquetry at the École Boulle in Paris, she began working at Elie Bleu, a company that produces watch and jewelry boxes for luxury brands. There she honed her skills in marquetry, often employing materials such as wood and mother-ofpearl. She explains, “Occasionally, we’d work on projects using other materials, such as an all-stingray box for Cartier, or a flat leather finish on an Hermès box. As there were scraps of material leftover, I asked my boss if I could salvage them, and that’s how I started experimenting and researching how to mix different materials in a marquetry.”

Multi-material marqueteur Rose Saneuil at work in her workshop

A decade ago she decided to set up her own company. “My idea was to offer decorations on boxes or furniture. At that time, I had absolutely no thought of doing miniature marquetry!” she reflects. “The year before I set up my own business, I took part in a marquetry exhibition, where I exhibited paintings. And my booth neighbor at the show was Bastien Chevalier. I was absolutely blown away by his work. We became friends, and it was he who, a year after we met, said to me when I was starting my own business, ‘Come here [to Switzerland], there’s room for you’ — a little phrase that changed my whole life,” she says.

Assembling the dial of the Piaget Altiplano Métiers d’Art Undulata. The particular piece she is placing in position is beetle elytra

In 2014, she began creating marquetry dials for Piaget, beginning with the Piaget Altiplano executed in wood marquetry. In the ensuing years, her true versatility unfolded on numerous Piaget watches, incorporating a diverse range of materials such as white and Tahitian mother-of-pearl, parchment, straw, leather and beetle elytra, culminating in the Altiplano Métiers d’Art Undulata which took home the Artistic Crafts award at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG) last year. The dial featured a composition of sycamore, straw, parchment, trout leather and beetle elytra in shades of green, blue and iridescent hues. “What interests me in materials are the different effects they can give. For example, mother-of-pearl and straw will catch the light while leathers will bring depth. I love the iridescence of the beetle elytra,” she explains. Beetle elytra produces a remarkably captivating effect reminiscent of gemstone. Saneuil admits, “It is the most challenging material I have worked with. The elytra is naturally bulging, and I work with flat materials. It took me more than two weeks of numerous tests and trials to find out how to lay it flat. And now, I am often asked how I do it but I say nothing!”

MULTI-MATERIAL MARQUETRY

Saneuil begins a project with an intention drawing in color, providing an initial visual representation of the project. This serves as a guide for identifying materials that match the intended effect and color palette. Following this, a technical drawing is created on a drawing software to assess feasibility. Miniature projects such as dials or jewelry require scrutiny to ensure that intricate details are not too small, while larger projects like paintings require consideration of material width limitations; wood veneers, for instance, often have limited widths. Utilizing the drawing software, Saneuil conducts a simulation of the final project by scanning each material individually and creating a pattern. With the subjects selected, each material undergoes specific preparation techniques. Due to their delicate or thin nature, certain materials cannot be precisely cut at very minute scales. Thus, to cut these fragments, Saneuil encloses the material between two slices of soft wood, sandwiching them to accurately cut each micro-shape pattern with a jigsaw.

A dial crafted with an astounding array of materials, including various types of wood (sycamore, tulipwood, speckled maple, mesh plane tree, burr walnut, ash, and madrona burr), along with white mother-of-pearl, Tahitian black mother-ofpearl, straw, parchment, beetle elytra, various leathers (lamb, calf, snake), mica, cock feather, and gypsum.

The multiple copies of the drawing are printed, and each piece of paper is affixed to its corresponding material. Saneuil then meticulously saws each piece individually. After all the pieces are cut, she assembles the pattern by adhering it to the support. The final steps involve sanding and polishing to achieve the desired finish. But evidently, the most impressive aspect of her work is her deep understanding of the different materials. Mastering these materials, in turn, would also mean mastering adhesives. Naturally, due to the distinct properties and characteristics of each material, they require different adhesives to achieve optimal bonding. “I have more than 10 different glues adapted to different materials. Every time I test a new material, I have to test the glue that suits best,” she explains.

The level of skill required in selecting, cutting and assembling countless, meticulously cut tiny pieces of material makes it all the more unsettling that the beauty of marquetry is often appreciated in a more understated manner. Unlike the deep, vibrant colors of enameling or the bold strokes of engraving, marquetry is quietly extraordinary. It’s only upon closer inspection or with guidance that one comes to realize that what initially appears as a painting is, in fact, marquetry. In Saneuil’s case, it not only captivates aesthetically, but also challenges preconceptions about the materials and techniques typically associated with this art form. Both for the visual impact and the highly developed skills necessary to create it, marquetry is well worth understanding and valuing.