News

The Master Chronometer: A Story of Triumph Over Tragedy

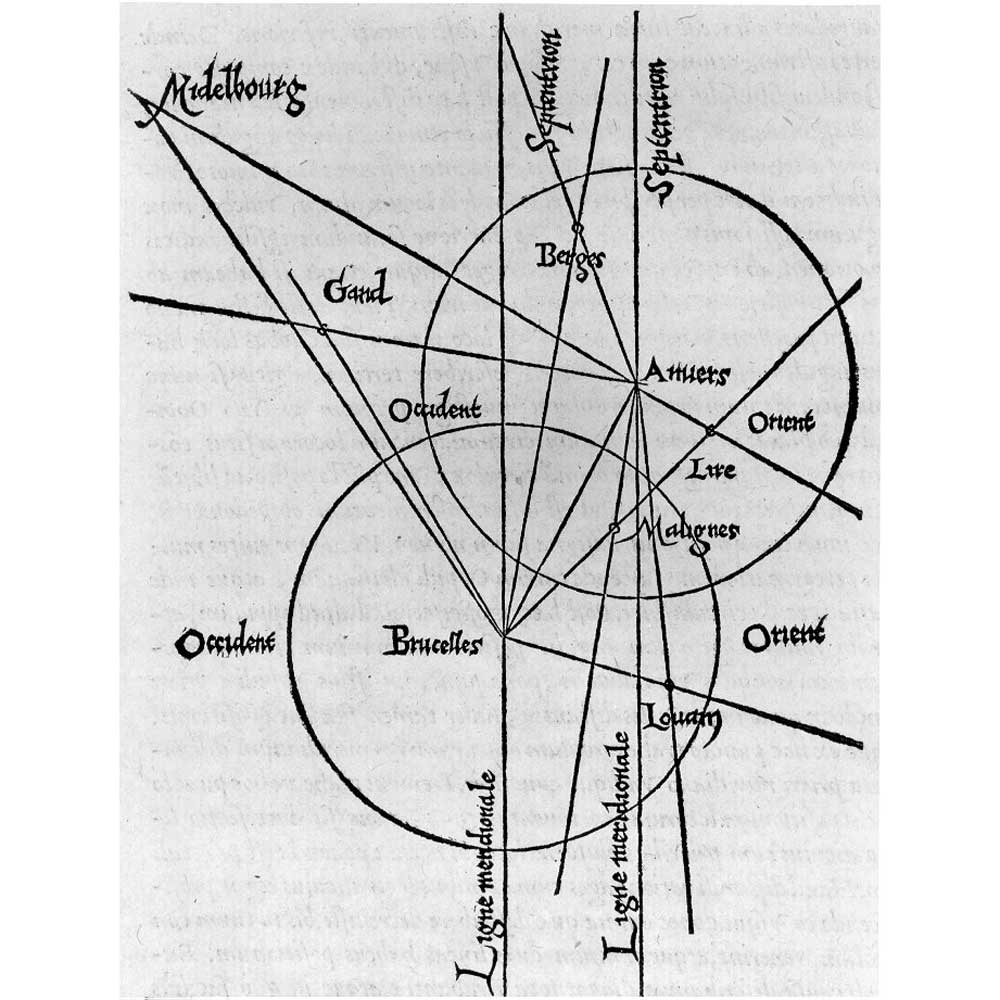

In 1707, errors in navigation caused by an inability to accurately keep time led to the loss of virtually an entire British fleet. Just a few minutes of inaccurate timekeeping caused the fleet to veer miles off course into rocks, resulting in the loss of up to 2,000 mariners. Determining longitude using a clock was first suggested in 1530 by a Dutch scientist and mathematician called Gemma Frisius. However, clockmaking was still nowhere near accurate enough for nearly two centuries following Frisius’s theoretical breakthrough. It took one of the worst British maritime disasters in naval history to spark a government to take drastic action.

Triangulation by Gemma Frisius. (Taken from: G. Frisius, Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione, Antwerpen 1553)

To qualify, the timekeeping device had to be accurate to within three seconds a day, a level that was not even met by the best land-based pendulum clocks of the era. The knock-on effect of this accuracy meant that ships’ longitude could be accurately determined within 30 miles after a six-week voyage. Sounds like madness in 2021, but in the early 1700s, this was miraculous. Harrison’s five timepieces were known as H1 to H5. Although he demonstrated the supreme accuracy of H4 and H5, the Board still would not award Harrison the prize until King George III got involved and insisted Harrison was awarded something. Along with a reduced financial reward, Harrison’s H5 was bestowed the title “Marine Chronometer” in 1773.

Harrison’s H5 was bestowed the title “Marine Chronometer” in 1773

Tested to high standards

By the mid-19th century, marine chronometers were in regular use. The issue of testing them became very real however, as they were essential pieces of safety equipment for ship navigators. The solution was to utilize the facilities at the European observatories including Neuchâtel, Geneva and Kew in London. These observatory trials led to movements undergoing periods of very stringent testing to determine if they were up to the title of “Observatory Chronometer”. Eventually, brands used the observatory trials to showcase their outstanding watchmaking skills, sometimes spending years tweaking movements to be as perfect as possible in preparation — like an athlete preparing for the Olympics.

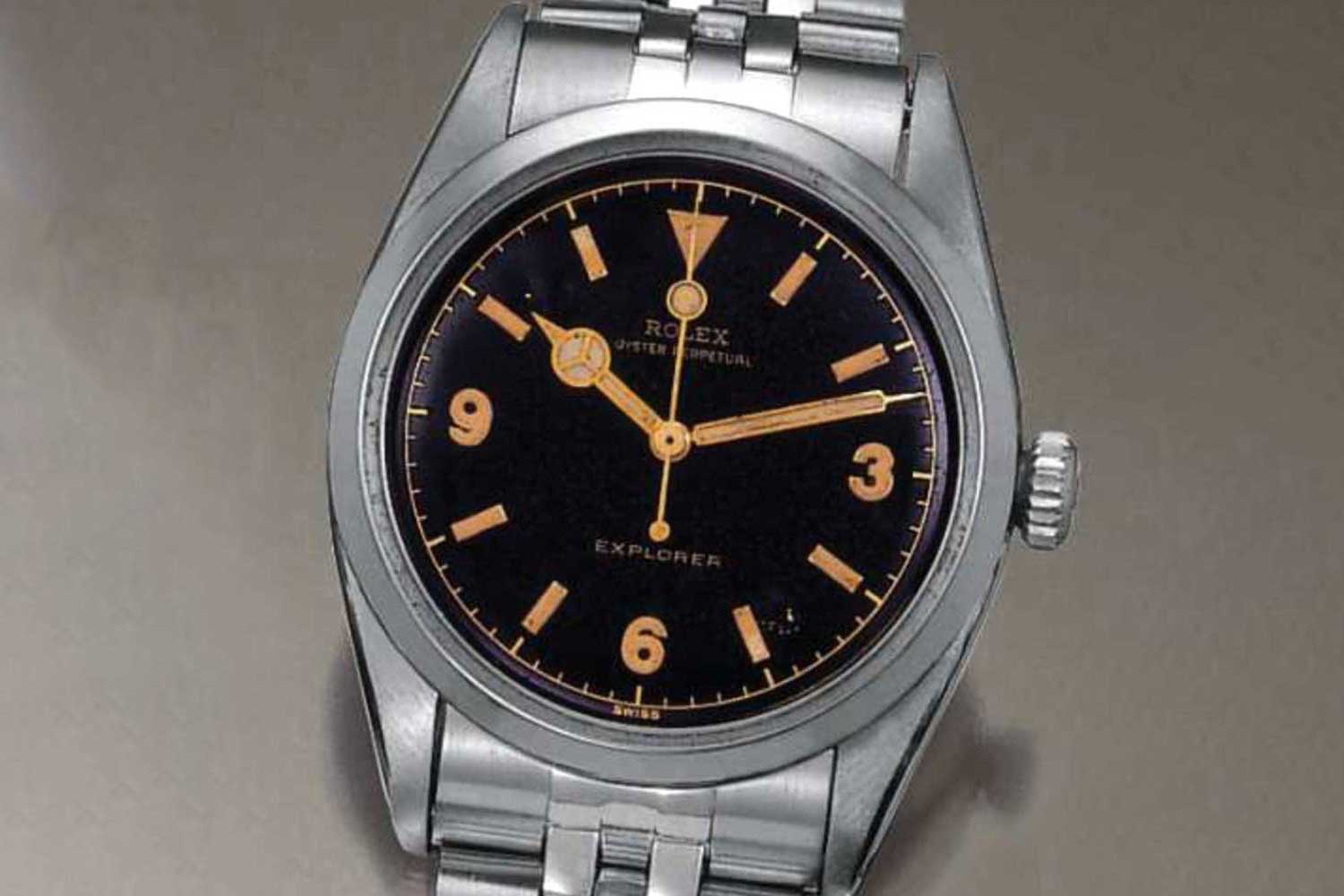

In the 1950s and ’60s, watch movements could be submitted for chronometer testing and would undergo a 30- to 50-day testing cycle, that would result in a certificate known as a “Bulletin de Marche”. This certificate gave details of each movement’s performance whilst under test and was supplied with watches alongside the guarantee certificate. I’ve handled a number of Officially Certified Chronometer (OCC) dialed vintage Rolex Oysters that included the Bulletin de Marche paper, thus allowing the watch to wear the esteemed OCC badge on its dial.

The Rolex Explorer Ref. 6350 with “pencil” hands was chronometer rated Officially Certified Chronometer (OCC)

The COSC standard tests the performance of the movement over a period of 15 days. To be clear, this is just the movement and not the fully assembled watch. Each movement has a white plastic dial fitted with two small black dots opposite each other to focus the camera that monitors the seconds hand every 24 hours. The movement is tested as a manual wind (i.e. the automatic mechanism is disengaged) and wound once a day at the same time each day. It is tested in five different positions and at three different temperatures — three o’clock, six o’clock, nine o’clock, dial up and dial down at the three temperatures of 8, 23 and 38 degrees Celsius. Each position and temperature get 24 hours, and then the timing is checked, hence the 15-day cycle. The timings are taken, and the average daily rate has to be within -4 and +6 seconds per day.

Going back briefly to in-house accuracy, brands can do a lot to beat even the COSC standards. Sure, having a watch COSC certified is a badge of honor for any Swiss-made wristwatch, but Tudor, for example, insists on higher levels of accuracy once the movement is back from COSC testing. The tested movement is then cased and undergoes another series of testing. The headline numbers are that Tudor’s in-house standard shaves four seconds off the COSC standard and insists on a variation between -2 and +4 seconds per day fully assembled. So where does a brand go next to prove its haute accuracy? Better call METAS…

Tudor has its own in-house facility where all the watches are tested to comply with the METAS Master Chronometer requirements

Tudor has its own in-house facility where all the watches are tested to comply with the METAS Master Chronometer requirements.

Tudor has its own in-house facility where all the watches are tested to comply with the METAS Master Chronometer requirements.

The watches are tested fully assembled in specialist equipment

The Master Chronometer status is an above-and-beyond measure and so, movements submitted for METAS evaluation must also have been through COSC testing to qualify. Alongside chronometry testing, the other headline test is magnetic resistance, and in the case of a Master Chronometer, to the level of 15,000 gauss. To be clear, this is a serious bout of magnetic force that a human would experience in only a tiny number of environments. The magnetic force in our natural environment is around 0.5 gauss. A scrapyard magnet will generally be around 10,000 gauss (known as 1 tesla), and an MRI scanner can be anywhere between 15,000 and 30,000 gauss (or 1.5 to 3 tesla). To pass the Master Chronometer tests, a watch has to operate perfectly when exposed to 15,000 gauss and then continue to operate unhindered following said exposure.

So, let’s take a closer look at the tests that each watch must undergo:

Swiss Made — The watch must qualify as Swiss Made, which currently means that 60 percent of all the manufacturing costs and manufacturing processes must occur within Switzerland.

COSC — The movement of the watch must have acquired COSC certification from the aforementioned Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres.

Precision — The tolerance for Master Chronometer is an average of 0 and +5 seconds, which shaves five seconds off the COSC standard. The watch is tested at two temperatures (23 and 33 degrees Celsius) and in six different positions (12 o’clock, three o’clock, six o’clock, nine o’clock, dial up and dial down). Additionally, the watch is tested at full power and with a third power on the mainspring (100 percent and 33 percent wound).

Anti-Magnetic Properties — The smooth functioning of the movement and watch during and after exposure to a magnetic field of 15,000 gauss.

Water Resistance — METAS checks a watch’s claimed waterproof qualities. So, for example, if a manufacturer claims a watch is depth rated to 200m, this is thoroughly tested.

Power Reserve — In a similar way to water resistance, METAS checks that the claimed power reserve is accurate.

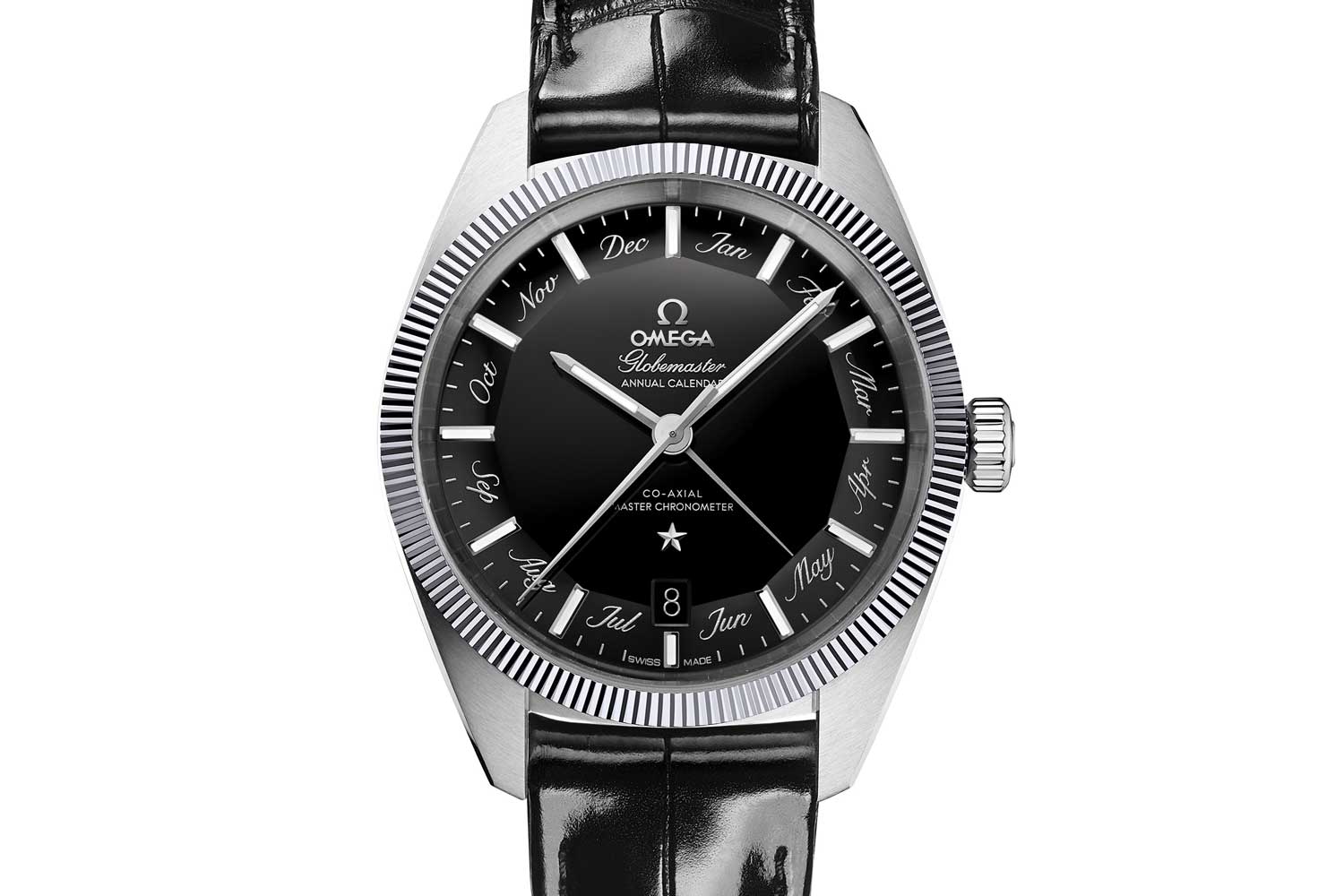

First in line: Omega

The first brand to be certified by METAS was Omega, with its Globemaster line in 2015. This was quite fitting as the name Globemaster was used as far back as 1953 on some Constellation watches. Always housing the brand’s finest movements, the Constellation and the Globemaster wristwatches have an applied star on the dial. The first Omega Master Chronometer was achieved using the brand’s co-axial 8900 caliber, with silicon hairspring and anti-magnetic alloys for movement parts such as the balance and lever. The 15,000-gauss resistance was, in fact, first debuted by Omega in 2013 in the Aqua Terra line. This part of the METAS certification is one of the most challenging and the reason that many brands cannot even begin to consider the Master Chronometer tests.

The original Constellation Globemaster from 2015 with a striking blue dial

The 2019 Constellation Globemaster Annual Calendar 41mm in steel with a black dial

The new Seamaster 300 Master Chronometer

Tudor’s first metas certified watch

So, what vehicle did Tudor use to deliver its first Master Chronometer? The Tudor Black Bay Ceramic. This watch is an interesting play on the brand’s smash hit dive watch family that has transformed the little brother in the Wilsdorf family into a major player in the industry. The BB Ceramic comes in a 41mm ceramic case with sandblasted finish, black ceramic bezel insert, black dial and a display caseback. The watch houses a new manufacture movement, caliber MT5602-1U, with a silicon hairspring that is anti-magnetic up to forces of 15,000 gauss, which is the lynchpin in the watch being Master Chronometer certified.

Stealth, quality and precision are the defining design tenets of the Tudor Black Bay Ceramic Master Chronometer

Caliber MT5602-1U

Tudor Black Bay Ceramic Master Chronometer

So, a three-century-long journey for the chronometer that began with a tragedy for the British Navy, sees its latest instalment from Tudor and Omega in watches that have their performance verified on your smartphone. Now that’s progress!