Patek Philippe

Patek Philippe Calatrava movement’s evolution through the years

Patek Philippe Calatrava the standard bearer for time-only dress watches

For more than 85 years, the Patek Philippe Calatrava has been widely regarded as the standard bearer for time-only dress watches. It dates back to the 1930s, a time of transformation wrought by the Great Depression. It was the watch that ushered in a new era for Patek Philippe with the two brothers Jean and Charles Stern at its helm. In contrast to the flamboyant styles of the previous decades as exemplified by the Gondolo, the Calatrava was round, yet unfaltering in its design, encapsulating the dynamics of modernism, namely Bauhaus – the ideas of “less is more” and “form follows function.”

While always keeping within the bracing paradigm of its elegant, minimalist philosophy, the Calatrava brimmed with many aesthetically differentiating details through the decades, from dial styles to case sizes. But equally, the movements as well as the order of priorities in designing them have evolved and shifted tremendously.

In charting the evolution of the most significant Calatrava movements, it’s apparent that their designs speak to intrinsically classic considerations in which form and function operate in a kind of recursive loop, right from the first 12-ligne hand-wound movement through to the brand’s first automatic calibre 12-600AT, the ultra-thin automatic calibre 240, culminating in the truly remarkable 30-255 in the newly launched Clous de Paris ref. 6119.

As a whole, this ensemble also serves as a broad survey of watchmaking – its preoccupations and progress through time from central seconds to automatic winding, slimness and ultimately high performance. Notably, for Patek Philippe, these pursuits were achieved while maintaining a high degree of care in construction and an exceptionally refined aesthetic that has shaped the conception of a dress watch movement as we know today.

Calatrava, the Hand-wound Movements of the Golden Age

The preeminent Calatrava ref. 96 was introduced in 1932. It was a small 31 mm watch that measured 9 mm in height. At that point in time, Patek Philippe relied on movements from LeCoultre in Le Sentier, so for the first two years of production, the Calatrava was equipped with a 12-ligne LeCoultre movement. As the company underwent a complete overhaul, the Sterns appointed Jean Pfister, a watchmaker and horologist, as the company’s technical director. Pfister was determined to build Patek Philippe’s in-house capabilities, and the calibre 12”’120 was the first movement developed under him. This movement powered all subsequent ref. 96 watches made between 1934 and 1973.

The Calatrava ref. 96

The in-house calibre 12-120 (Image: Bukowskis)

With the Calibre 12-120, Patek Philippe uphold its reputation for perfection

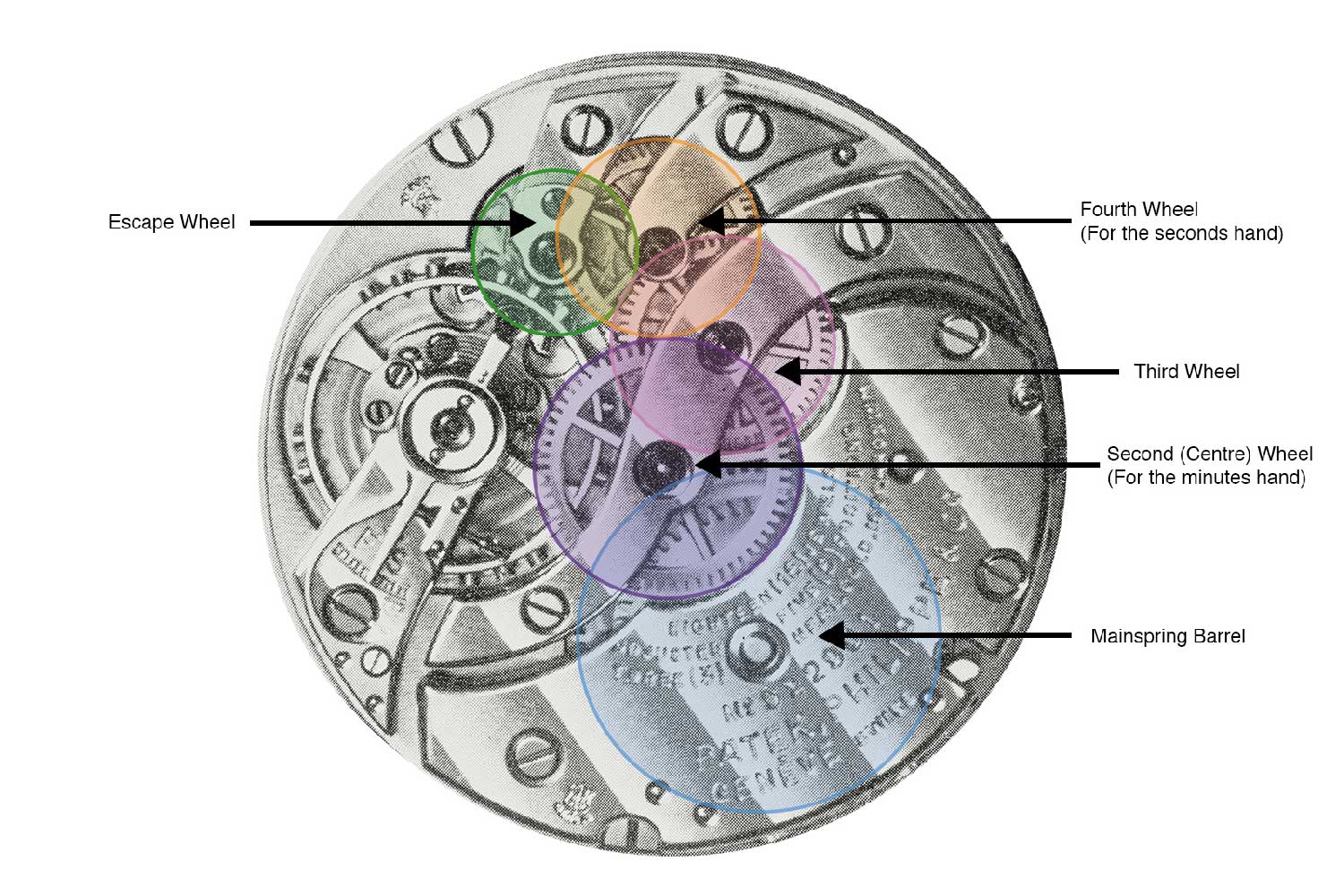

The calibre 12”’120 was characterised by a traditional Genevan architecture and was intended to uphold the reputation the firm had established with its pocket watches. As seen in most movements during that time, the calibre 12”’120 was designed with a subsidiary seconds, in which the fourth wheel, making one revolution a minute, is positioned at six o’clock to drive the seconds hand directly. This traditional layout optimises the volume of the movement by spreading out the moving parts on the same plane. The escape wheel and fourth wheel are held in place by their own bridge while a separate elongated bridge spanning the movement is designated for the second and third wheels.

The wheel train layout of the calibre 12-120

As a result, such multi-bridge constructions became the preserve of high-end watches or fell victim to cost-cutting measures after the Quartz crisis. Some notable details of the 12”’120 include the black-polished steel plate on the cock that holds the escape wheel as well as the shape of the bridges which allow for sensuous anglage and sharp inward angles.

A close-up of the main bridge with a sharp inner corner (Image: Phillips)

In 1949, Patek introduced the 12”’400 calibre, which was, for the most part, similar to the 12”’200 except for the design of its regulator and the additional shock-resistant suspension on the balance wheel.

The Patek Philippe calibre 12-400 (Image: Vintage Gold Watches London)

The brand's first serially produced anti-magnetic watch, the ref. 3417, equipped with the calibre 12-400 (Image: Phillips)

Calatrava’s quest to feature central seconds in its movement

At the time, one of the brand’s most fascinating inquiries was its quest for central seconds. While having a centre seconds hand is customary in modern watches today, movements back then were designed with a subsidiary seconds in which the gear train terminated at six o’clock to drive a small seconds hand directly.

In 1939, Patek Philippe’s 12-ligne calibre spawned the 12-120 SC (SC designated seconde centrale), which was used in the ref. 96 as well as the 565 and the 570. The movement incorporated a sophisticated indirect centre seconds mechanism produced by Victorin Piguet. It was one of the earliest movements in watchmaking to feature a central second.

The Calatrava ref. 565 with an indirectly driven central seconds (Image: Phillips)

The calibre 12-120SC incorporating a notably elaborate indirect central seconds mechanism (Image: Antiquorum)

Calatrava’s quest to feature central seconds in its movement

Visually akin to a chronograph, the mechanism comprised of three additional gears driven off the fourth wheel at six o’clock. The gears are located above the going train so as to relocate the seconds back to the middle. While this solution has become a standard practice to achieve an indirect central seconds, Victorin Piguet designed a notably elaborate set-up that included a pivoted lever to support an intermediate wheel.

Patek Philippe introduced an ingenious movement marking a significant breakthrough

Later in 1949, Patek introduced the 27 SC, an ingenious movement with a directly driven central seconds. Although modern movements are usually designed with a central seconds in which the fourth wheel is positioned right in the middle to drive the seconds hand directly, this results in the centre (or second) wheel, which drives the minute hand, being positioned elsewhere. As such, an additional set of wheels – often driven off the third wheel – is once again needed to relocate the minutes back to the middle.

Logically, it is more efficient to design a movement with an indirectly driven minutes than an indirectly driven seconds as the fourth wheel is the fastest spinning wheel in the gear train and also the one with the least torque. Additionally, it is worth noting that the auxiliary wheels required in both approaches naturally contribute to the added height in the movement.

The calibre 27 SC in the Calatrava ref. 570 (Image: A Collected Man)

The calibre 27 SC achieves both a directly driven seconds and minutes by locating the wheel second and fourth wheels in the middle (Image: A Collected Man)

The calibre 12-600 AT is finest automatic movement

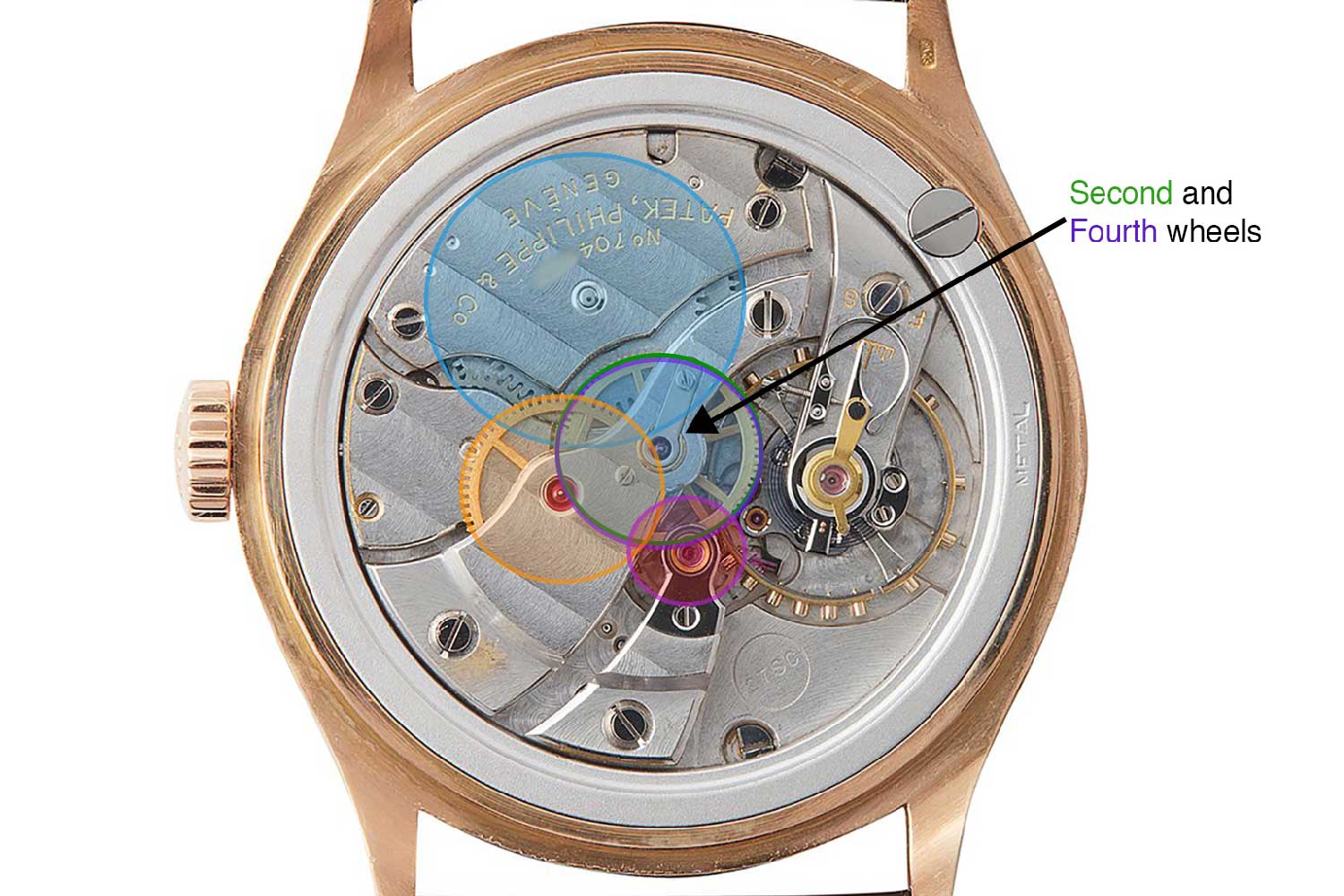

In 1953, Patek Philippe introduced its first self-winding movement, the calibre 12-600 AT (AT designated automatic winding) in the landmark ref. 2526. The watch was significant for combining three of the brand’s technical innovations – an automatic winding mechanism, a Gyromax balance and a water-resistant case.

The landmark ref. 2526 equipped with the brand's first self-winding movement, the 12-600 AT (Image: Phillips)

The elaborately constructed calibre 12-600 AT

To further differentiate itself from the other automatic systems in the market, Patek Philippe devised a complex, more efficient winding mechanism. It was centred on an eccentric wheel that is driven by the rotor. This wheel drives a pair of rockers that carry a pair of pawls, which in turn interact with the teeth of a ratchet wheel, winding the mainspring.

Introduced in 1951, the Gyromax is characterised by turnable weights with a cutout design to ensure that the one end is heavier. Inertia can then be increased by pointing the heavier side outwards. Impressively, the balance is also fitted with an overcoil hairspring. These were significant refinements in those days and were rarely found in the same movement.

Further improvements were made with regards to the complex winding system and it was later was succeeded by the legendary 27-460. This version saw some other refinements including a ball bearing instead of the jewelled rotor bearing as well as an adjustable stud holder. It was also in this movement that the Gyromax came into its own and was used independently.

Calatrava ref. 3520, The Ultra-thin Hand-wound

The enthusiasm for marrying function and style paved the way for the rise of ultra-thin watchmaking in the 1950s and 1960s. Patek Philippe’s response was the Calatrava ref. 3520 in 1965. It was characterised by a Clous de Paris, or hobnail bezel and advertised as “the flattest waterproof watch in the world” at the time of its introduction.

The ultra-thin Calatrava ref. 3520 with the characteristic hobnail bezel (Image: Watch Box)

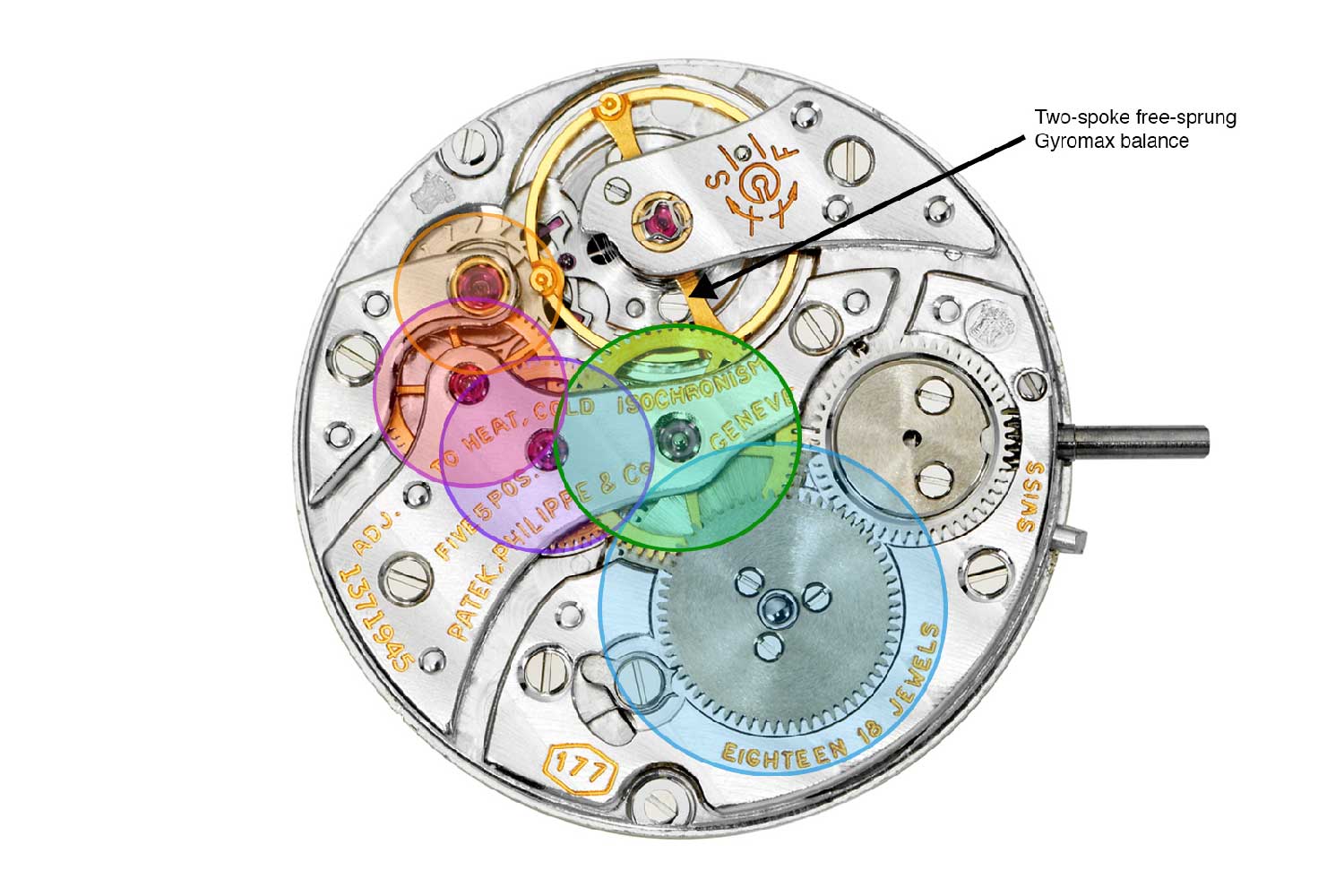

The Patek Philippe calibre 177 based on the venerable F. Piguet 21

Thus, due to the atypical position of the fourth wheel, the subsidiary seconds hand was often omitted in the watches it inhabited, and central seconds was avoided to preserve the original intent of the calibre, which was slimness.

The movements offered a power reserve of approximately 42 hours and was fitted with a Gyromax balance that ran at 2.5 Hz in the cal. 175, while the cal. 177 beats at a more modern 3 Hz.

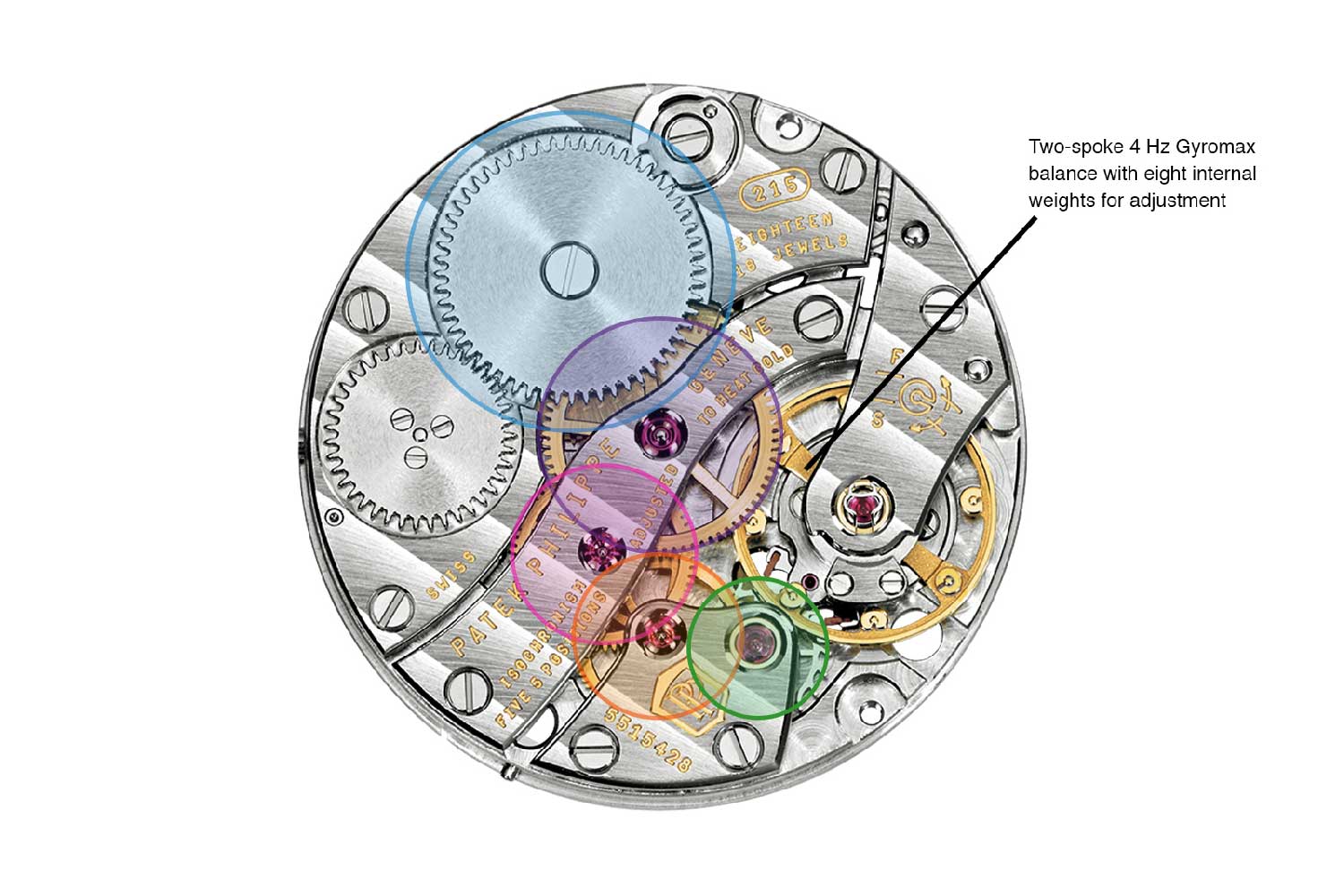

In 1974, calibre 215 PS is introduced as the successor to the 12-120

In 1974, Patek Philippe introduced the calibre 215 PS, a 10-ligne movement that was conceived as a successor to the 12-120 and the suite of other 10-ligne movements such as the cal. 23-300. It remains a staple in the Calatrava line and can be found in many notable references such as the ref. 3960, ref. 3919, ref. 5196, ref. 5116 and ref. 5119.

The ref. 3960 with an Officer's case, launched to commemorate the firm's 150th anniversary in 1989 (Image: Christie's)

The calibre 215 PS powers a majority of modern Calatrava models

However, it successfully manages a tricky balancing act between performance and aesthetics with respect to cost. Without a doubt, this is a reflection of the seismic changes brought about by the Quartz crisis, which had changed the rules of the game in terms of movement design, with performance now playing a more critical role.

The Workhorse Automatic represented by Calatrava ref.5296

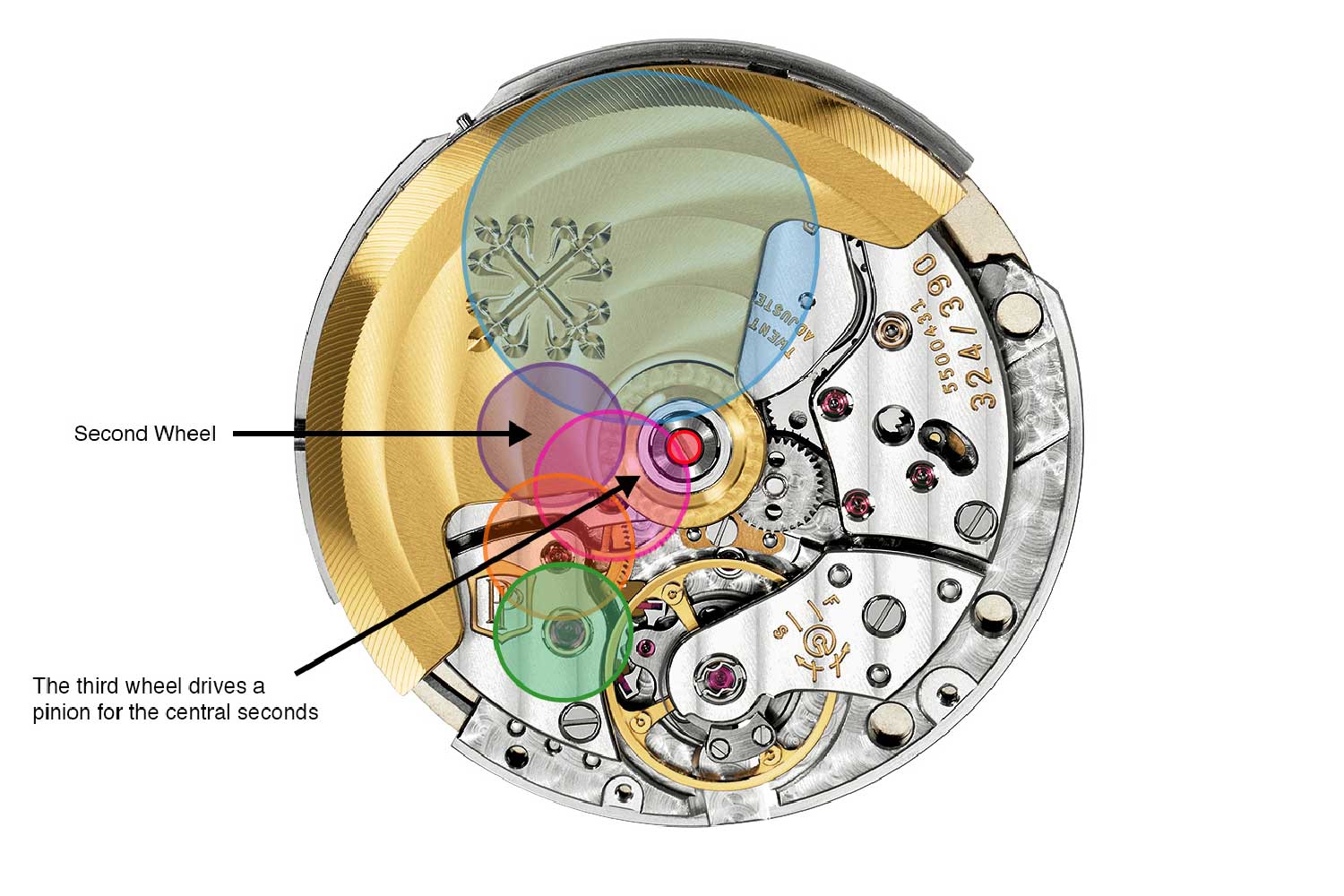

In 2006, Patek introduced the ref. 5296, a Calatrava that was closely inspired by the ref. 96 but was conceived to meet modern demands. It was powered by the workhorse automatic calibre 324 SC, which came with an indirect central seconds as well as a date display. The movement is a successor to the calibre 315 and powered a majority of the Nautilus from 2007 to 2019.

The ref. 5296R with a 38mm case, a central seconds and a date display

Patek Philippe calibre 324 SC

The Patek Philippe Calatrava - 324 SC employs an ingenious solution to include an indirect central seconds without any additional gears.

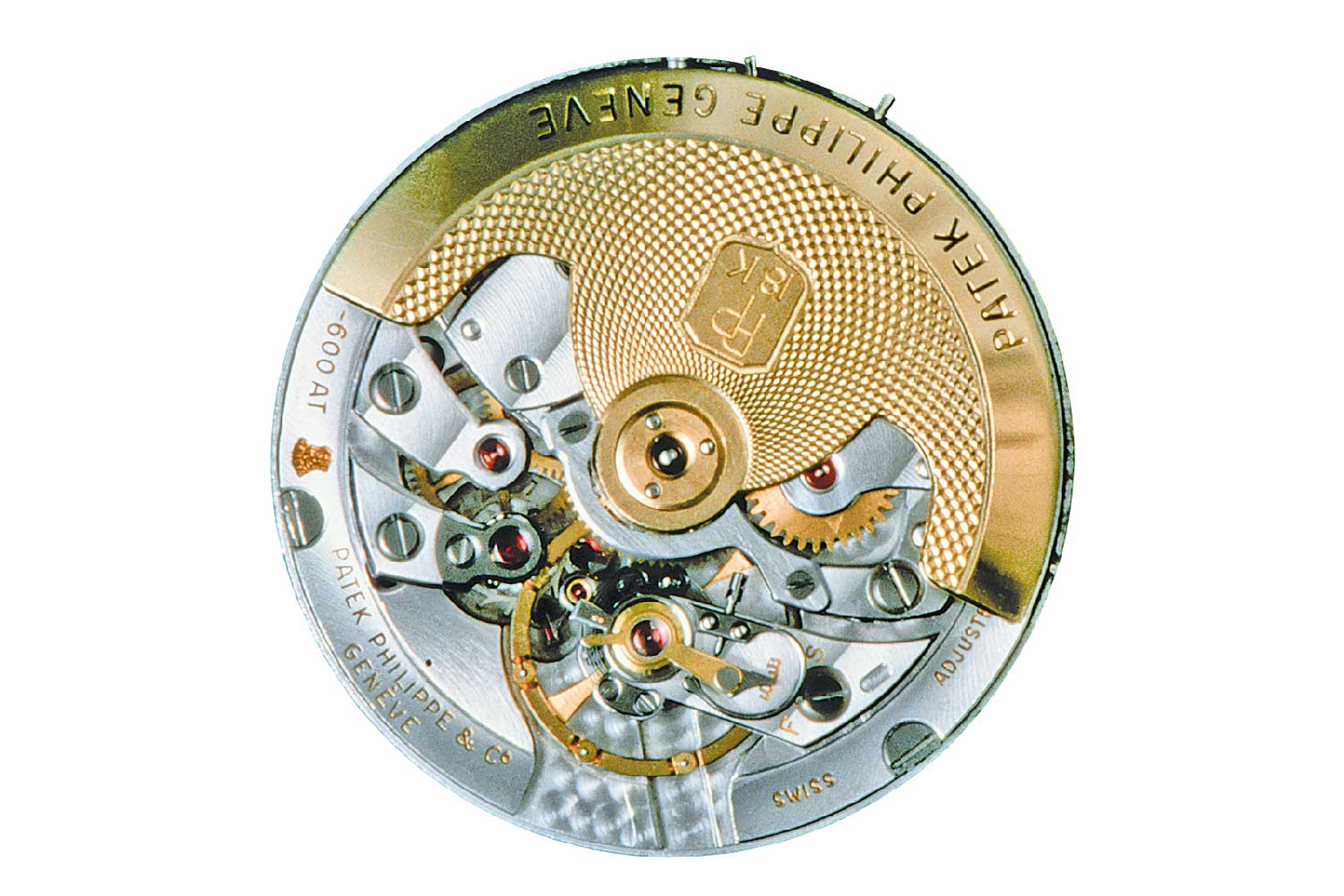

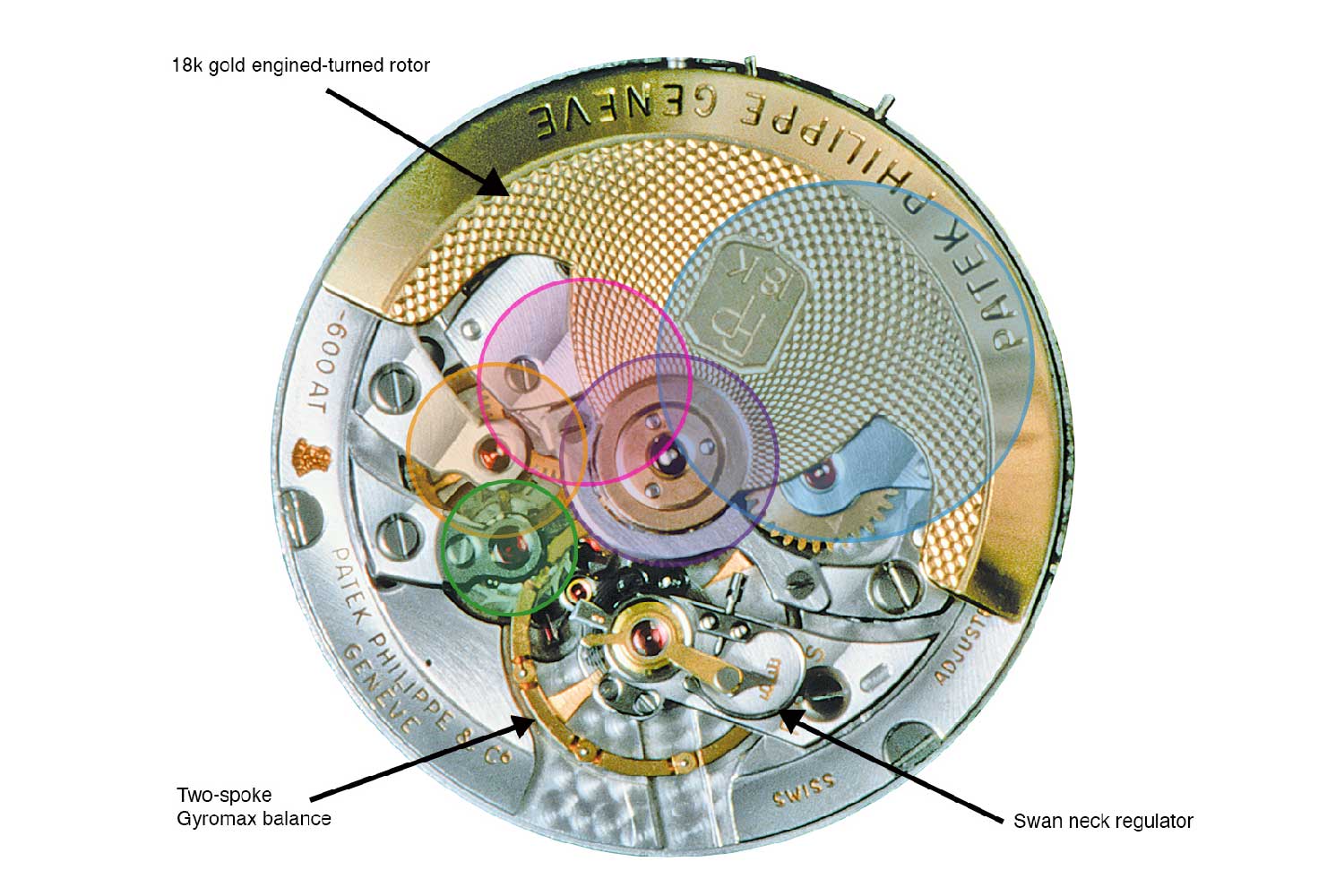

The Ultra-thin Automatic

The ultra-thin self-winding calibre 240

The ref. 6006G, one of the most distinct modern Calatravas.

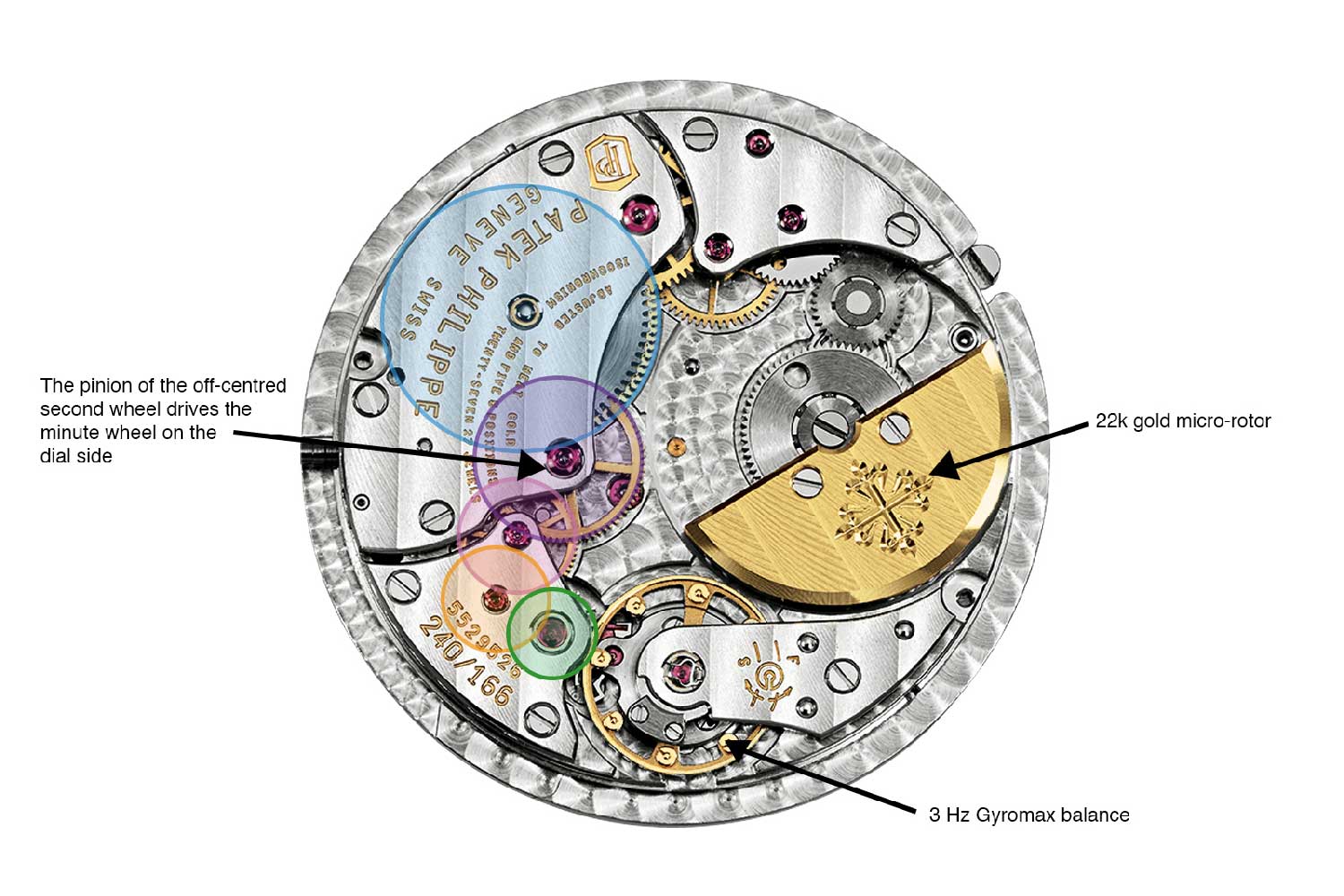

What distinguished the ultra-thin calibre 240 from other micro-rotor calibres at that time was its supremely elegant architecture wherein the entire transmission system, from the automatic winding wheels and barrel to the going train and the balance wheel, were arranged in a shape of a crescent on one side of the movement, leaving room for the off-centred micro-rotor on the same plane.

As a result of this crescent-shaped gear train arrangement, the fourth wheel, onto which the seconds hand is mounted, is located in a rather unusual position at eight o’clock when viewed from the case back. Hence, with the exception of a few watches, most notably the 6000 and 6006, the seconds hand would typically be omitted.

While the self-winding Calibre 240 has been optimised in many respects since its debut, it still retains its original structure. It runs at a frequency of 3Hz, but now with a Spiromax hairspring for improved isochronism. The tooth profiles of the going train were also further optimised to reduce wear, contributing to its 48-hour power reserve as well as boosting long-term reliability.

The High Performance Hand-wound

The Clous de Paris ref. 6119 with a 39 mm case equipped with the superb calibre 30-255 PS

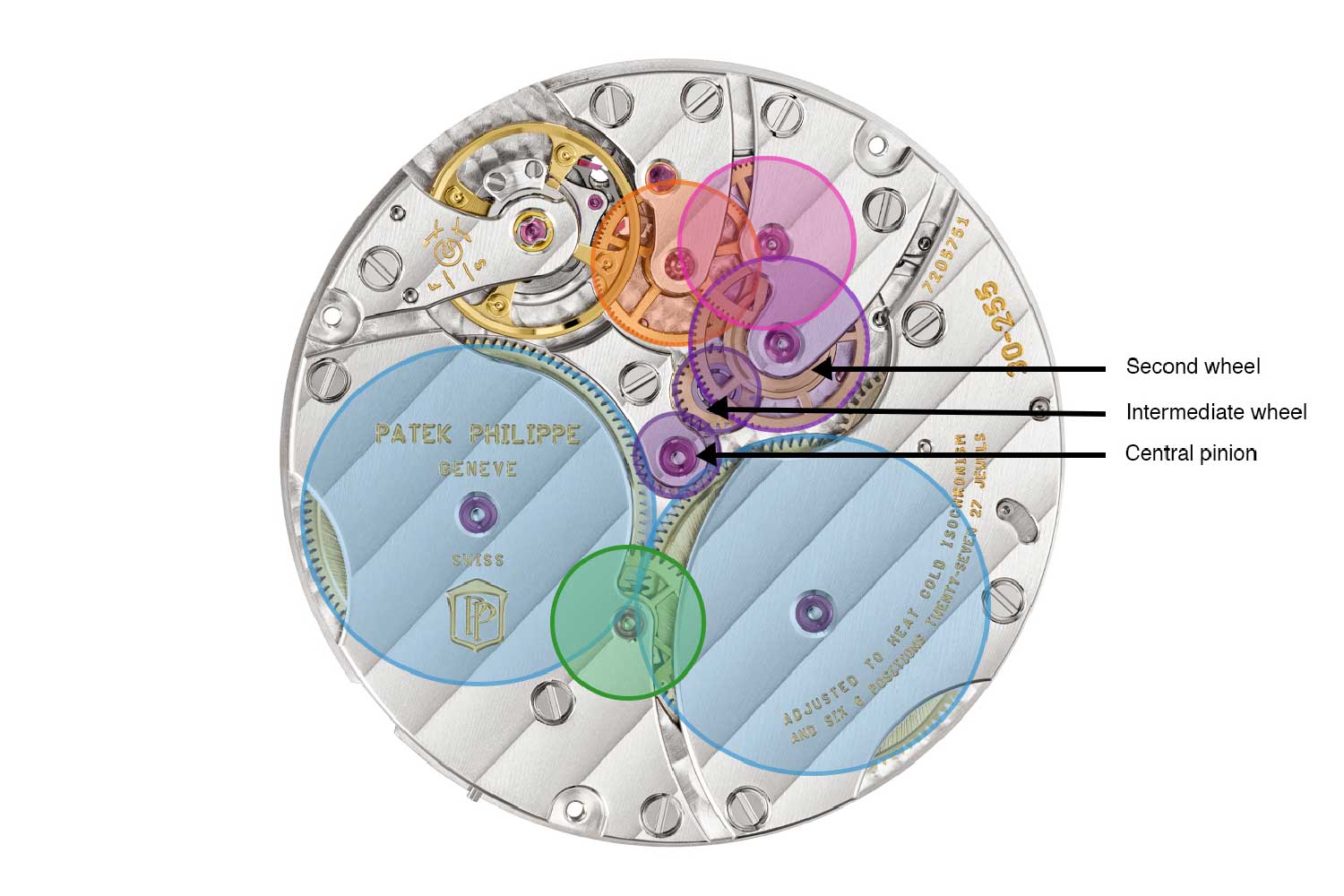

The brilliantly engineered calibre 30-255 PS with double barrels and a balance with impressively high inertia.

In this case, a greater torque was required to power a balance wheel with a frequency and inertia that are comparatively higher than other movements from Patek Philippe. It beats at a rate of 28,000 vibrations per hour and a moment of inertia of 10 mg/cm2 – twice the inertia of the brand’s other 4 Hz movements. The combination of a high balance power and a power reserve of 65 hours is all the more impressive in light of its height and is a testament to its exceptional design.

Apart from maintaining the height of the movement, the two pinions, which are small and solid, are also ideal in the face of high torque, as they effectively serve as the great wheel of the movement right after the barrels. The spokes of the wheels eventually vary down the gear train, with the third and fourth wheels being the thinnest and lightest. Impressively, the movement also incorporates a stops-seconds mechanism that is made up of two pivoted levers along the periphery of the gear train for precise time-setting.

Additionally, because of the multiplicity and sinuosity of the bridges and cocks, the movement is visually impressive and ultimately represents a masterclass in delivering high performance with a truly inspiring design.