Feature

Omega’s Magnum Opus

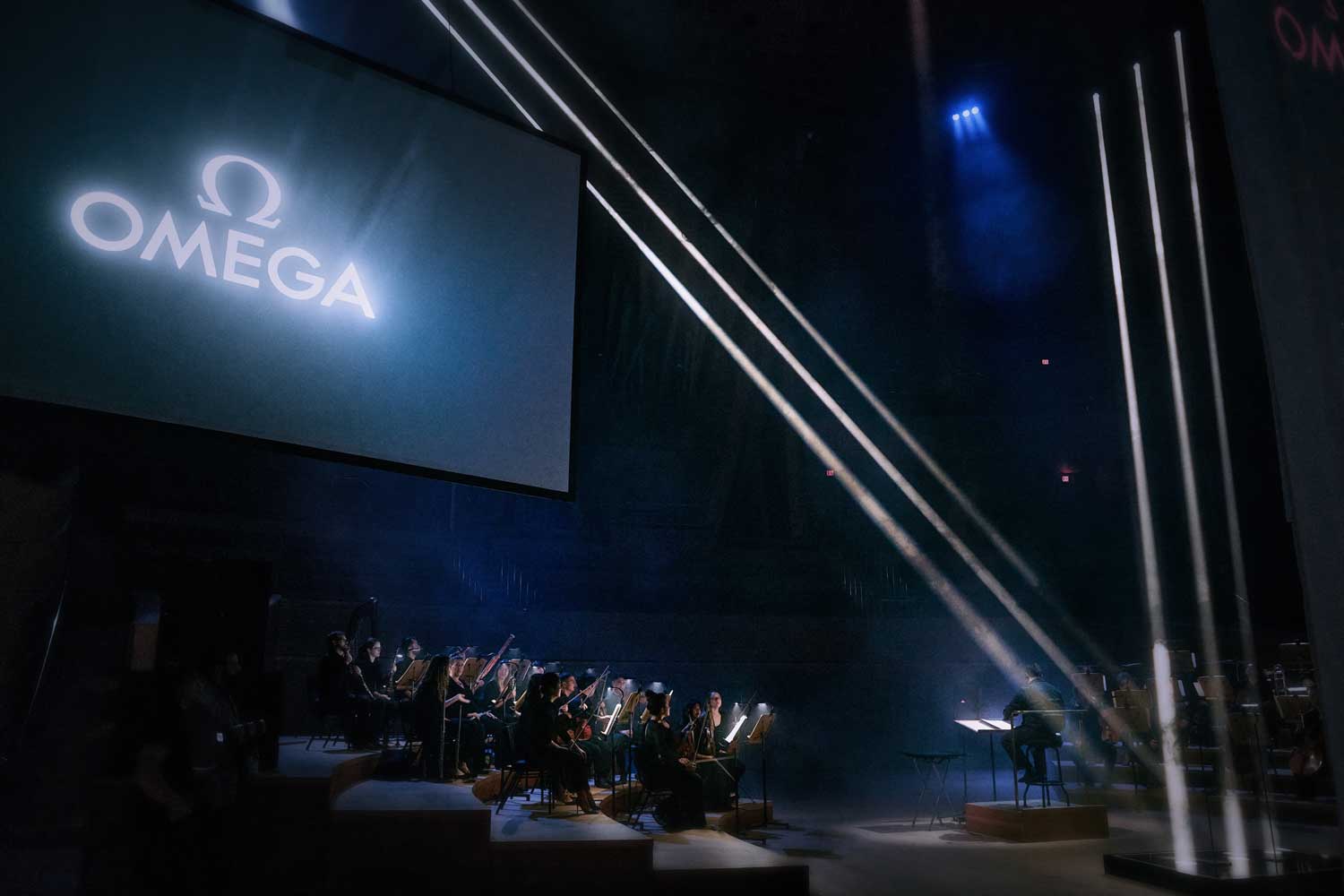

The event was held at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, widely acclaimed for its acoustics and architecture – a structure of undulating waves wrapped in stainless steel. Funded in large part by the Disney family and company as a contribution to the arts, the concert hall has been the home of the city’s philharmonic orchestra and chorale for almost two decades, and was designed by none other than Frank Gehry, one of the 20th century’s most celebrated architects. Just like Gehry’s revolutionary, deconstructivist body of work, Omega had picked a perfect location to reveal what would turn out to be a pivotal moment in its history and the beginning of a new era for the brand.

The Walt Disney Concert Hall designed by Frank Gehry

An orchestral performance heralded the arrival of Omega's Magnum Opus

The Olympic torch was lit at the LA Memorial Coliseum during the last stop of the press trip

The opening ceremony of the 1932 Summer Olympics was held at the LA Memorial Coliseum which had a seating capacity of 105,574 at the time (photo: IOC)

A timing board with eight Omega split-seconds pocket chronographs that was used to time track & field events

One of the thirty Omega split-seconds pocket chronographs that saw action at the 1932 LA Summer Olympics

Atelier d’Excellence is Omega's premier watchmaking department

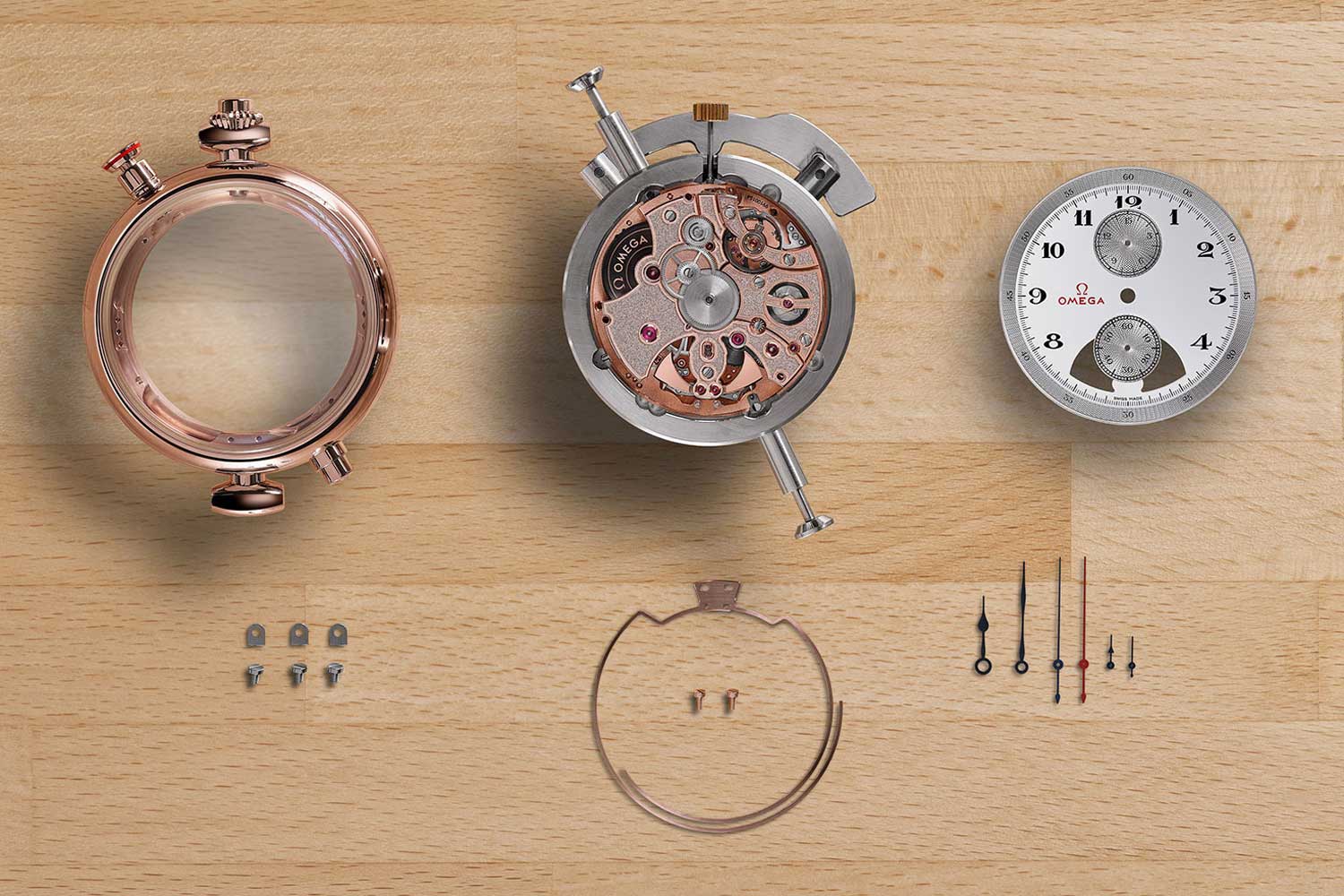

Dial side of the Caliber 1932

Movement side of the Caliber 1932

Here's a look at the inner workings of the repeater mechanism: The pair of tweezers is holding the chronograph seconds wheel with its two snail cams; the minute counter wheel is hidden underneath the bridge with the large jewel; the rack gathering mechanism which reduces "dead time" is to the right of the chronograph seconds wheel

The dial side of the movement reveals the chronograph wheel train, the exposed repeater hammers and the repeater wheel train that links the small secondary barrel to the magnetic governor

Without an isolator system, there will be added friction between the clamps and the teeth of the split-seconds wheel as that is the only location where the braking force is applied and the oscillator will experience a drop in amplitude as the immobilised split-seconds wheel is not isolated from the wheel train. Think of the isolator as a separate clutch system for the split-seconds wheel. After one timed event is recorded and the split function is reset, the clamps and isolator are released, and the roller jewel pushes against the heart-shaped cam for the split-seconds hand to smoothly catch up with the chronograph seconds hand. Being at the top of the hand stack, the split-seconds hand is placed above the chronograph seconds hand for a cleaner layout, making it easier to read singular timed events as the chronograph seconds hand runs in the background timing the overall elapsed time.

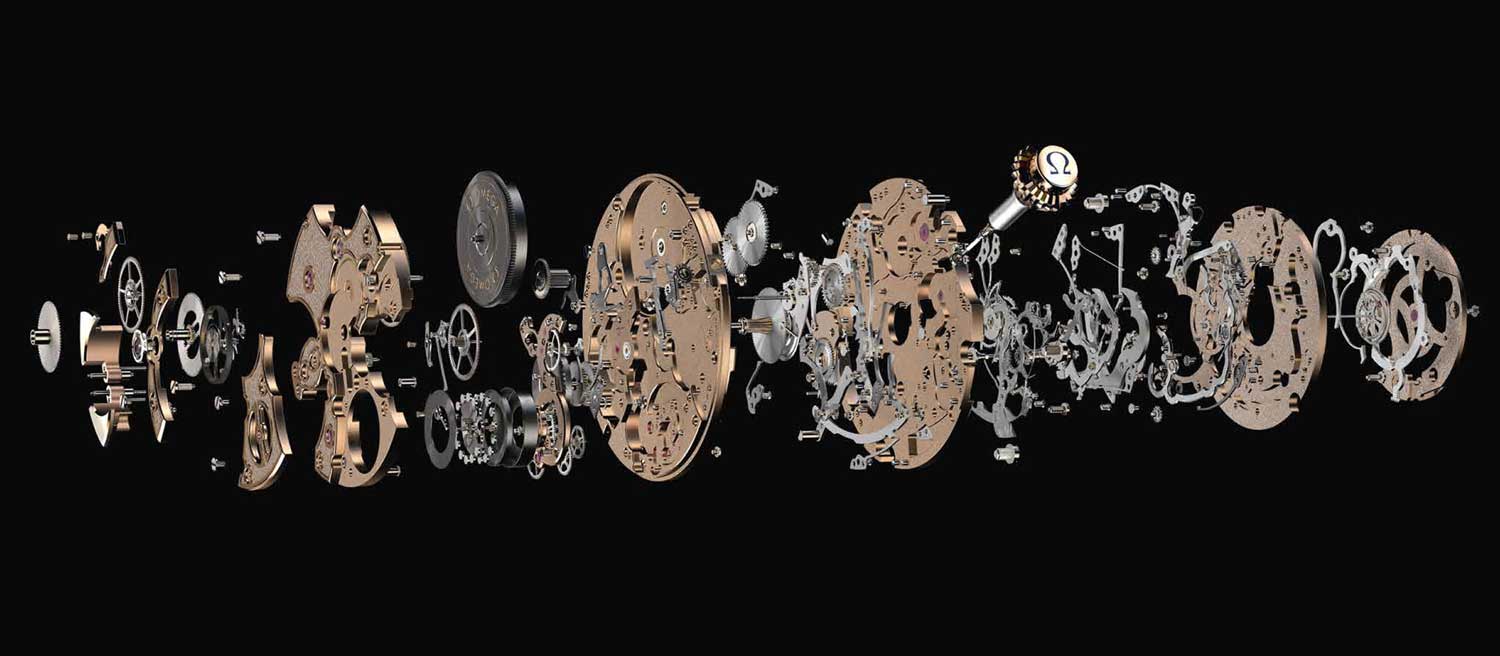

A complete view of all 575 components of the groundbreaking Caliber 1932

Olympic 1932 Chrono Chime

Olympic 1932 Chrono Chime caseback

Applying white enamel to the solid white gold dial plate. Multiple layers of enamel are required to give the dial its rich milky color.

Any imperfections or cracks that appear in the enamel during firing would mean restarting the whole process from the beginning. Enamel dial production is laborious and known for its high failure rate.

Pad printing of the Breguet numerals and minute track in black "Petit Feu" enamel. The dial cutouts for the hammers and the subdials are done after the printing process.

The guilloché pattern on the rehaut and subdials is extremely refined and meant to resemble sound waves

The repeater gong is made of a single piece and its length customised to a particular case after testing

The 18K Sedna gold repeater hammers are reinforced with an insert of hardened stainless steel

The anechoic (meaning non-reflective or non-echoic) chamber where the Chrono Chime's repeater is tested

The shielding surrounding the anechoic chamber prevents reflections and intrusions of sound or electromagnetic waves so that the mic only picks up sound directly from the source

The hands are blue PVD-coated to mimic the aesthetic of blued steel but will not tarnish over time. The chronograph seconds hand is CVD-coated and the split-seconds hand painted with a red varnish.

A Sedna gold movement in a Sedna gold case is a pairing that simply fits

The pusher that activates the repeater features a debossed musical note

The leather strap of the Olympic 1932 Chrono Chime can be easily removed by twisting the two prongs at the lug end

The Olympic 1932 Chrono Chime can be placed in the provided leather case and worn around the neck as a stopwatch

If you prefer to wear your Olympic 1932 Chrono Chime as a pocket watch, simply switch to the included braided leather cord with Sedna gold hardware

The Chrono Chime's handmade wooden boxes with different resonance plate designs and the acoustic wave pattern carved into the pull-out tray

Sheets of spruce from the Risoud Forest are handpicked by craftsmen for their unique acoustic properties to fashion the resonance plate

Fitting the wooden anchors that will hold the Chrono Chime in place on the resonance plate

Ensuring the wooden anchors are perfectly level

Speedmaster Chrono Chime

Speedmaster Chrono Chime caseback

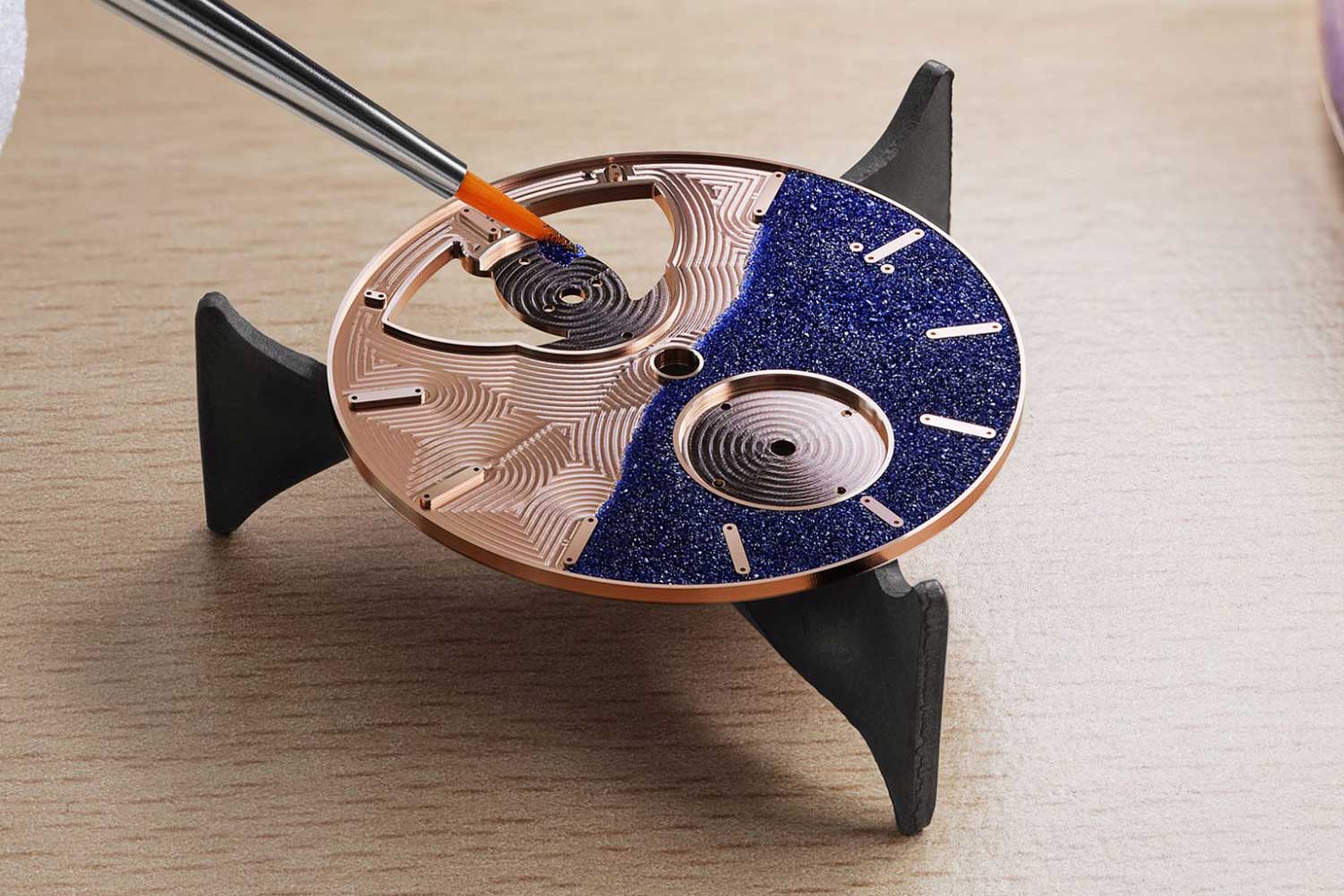

Grinding Aventurine glass into a powdered mixture

Grooves are cut into the solid 18K Sedna gold dial plate before application of the Aventurine mixture for better adhesion

The hour indices are made of 18K Sedna gold, diamond-polished and then filled with Super-LumiNova

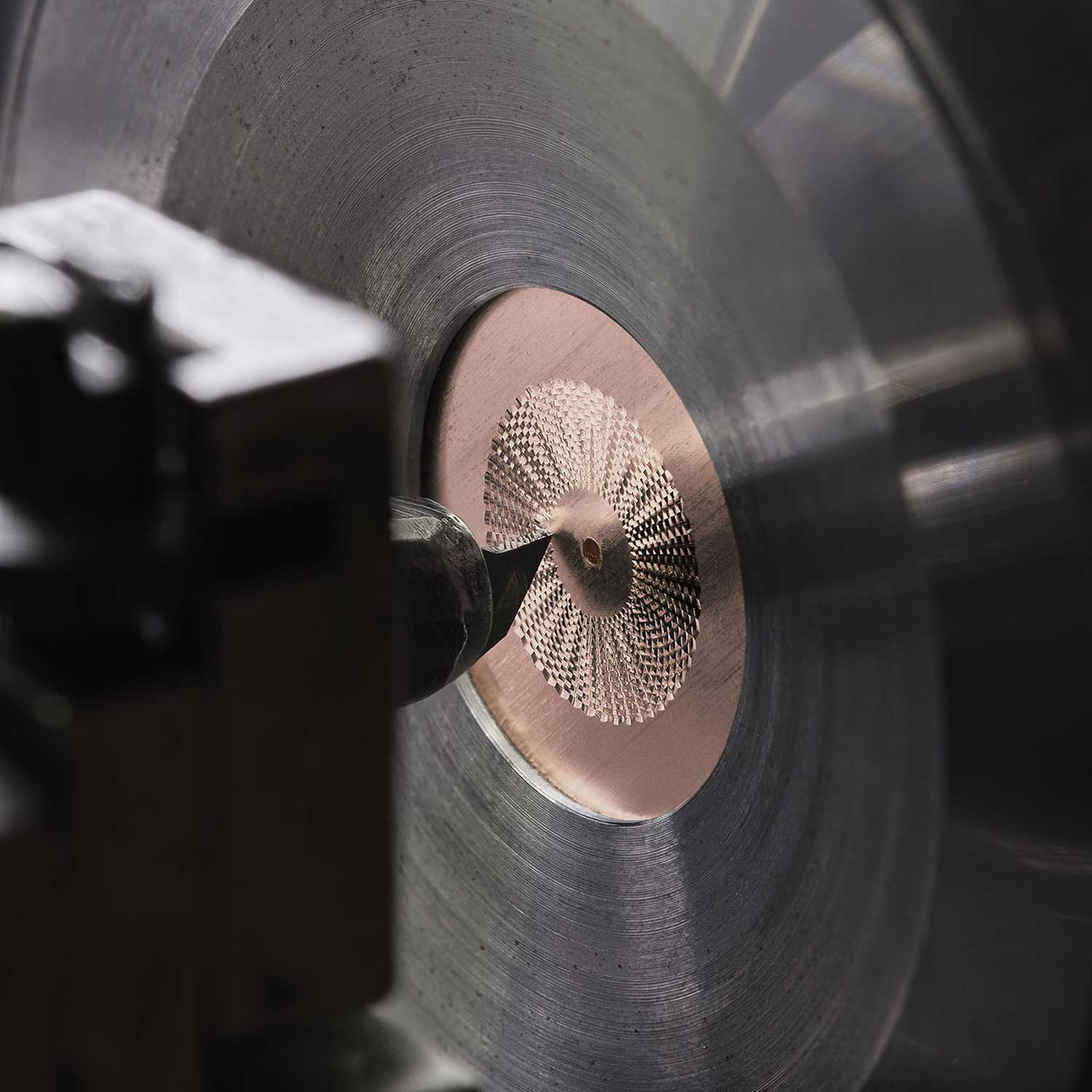

The acoustic wave pattern on the Speedmaster Chrono Chime's subdials is carved using a traditional rose engine

Carving the guilloché pattern onto the inner flange is particularly challenging due to small surface area available

Setting the red-tipped split-seconds hand onto the top of the hand stack

Sealing up the dial with the 18K Sedna gold bezel with Aventurine glass insert

The Speedmaster Chrono Chime comes with Omega's three-link brushed and polished bracelet in solid 18K Sedna gold

Despite its 45mm width, the Speedmaster Chrono Chime looks great even on a 7-inch wrist. Must be all that Sedna gold talking.

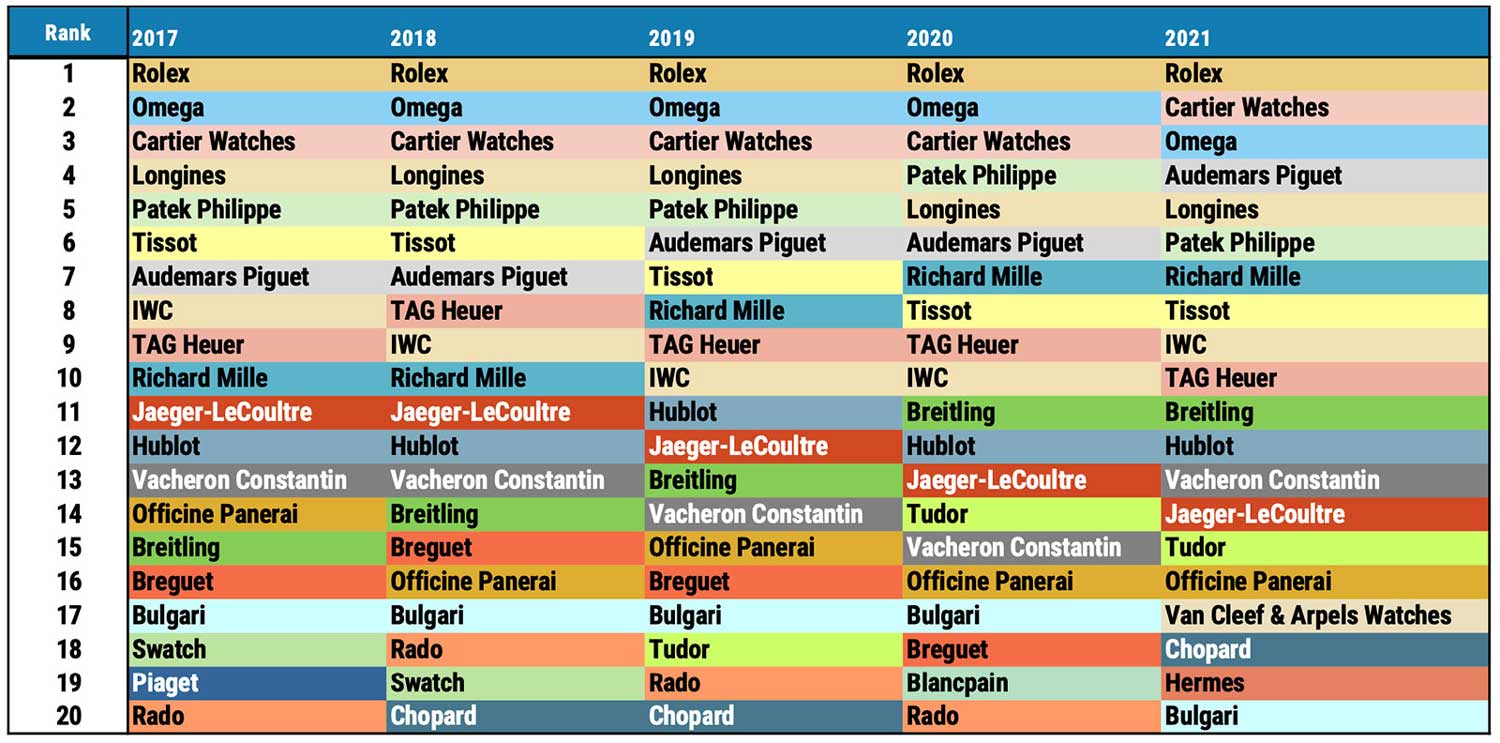

To understand the Chrono Chime’s significance beyond the scope of its mechanical ingenuity, we have to examine Omega’s position within the Swatch Group’s hierarchy of brands. Within this structure, Omega sits somewhere in the middle with high watchmaking big brothers Breguet and Blancpain above, and more accessibly priced juniors Longines, Rado, Tissot, Mido, and Hamilton below it. While this may not be the Group’s crown jewel in absolute watchmaking terms, it is more akin to a do-it-all performance brand that still manages to achieve success in every area of its portfolio, contributing the most to the Group’s overall bottom line.

It is within this context that this “flex” by Omega made me wonder if it might alter its position within the established order of the Swatch Group’s brands. Was Omega moving up the pecking order? Was it preparing itself for a higher form of watchmaking, to position itself further upmarket or to leverage its massive industrial production capabilities and maybe bring high complication watchmaking to a wider audience? At the group press interview, I posed those questions to CEO Raynald Aeschlimann. In his response, he explained that the Chrono Chime with its limited production represents a small, exclusive part of Omega’s portfolio, which has always been multi-product. It is not the brand’s intention to disrupt the established order, or to intrude into the market space of sister brands Breguet and Blancpain. Instead, the intention is to remind audiences of Omega’s rich history in professional sports timekeeping, and create a product that is in-keeping with its DNA and in particular a certain minute repeater from its history. If you think about it, Omega could have only developed the Chrono Chime with the expressed approval from on high, from Nick Hayek Jr. himself. For now, it will remain firmly in the haute horlogerie segment and while we may see some trickle down effects where technologies developed from this project find their way into other product lines, there are no plans to expand high complication-level watchmaking at a more affordable price segment.

Watch the full group press interview with CEO Raynald Aeshlimann here:

The original Omega De Ville Central Tourbillon from 1994

The updated 2020 Omega De Ville Central Tourbillon

Top 20 watch brands by retail sales from 2017 to 2021 (image: Morgan Stanley)