Reference

The Complete History of the Chronograph Movement Part 2: 1990s – 2000s

As the product identity of watches expanded beyond their functions, the chronograph began to evolve in three main separate directions, each reflecting a different pursuit. First, there are the haute horlogerie chronographs for which aesthetics, not just in terms of dial and case design but also movement architecture and finish, began to take on a new level of importance. Second, new materials and technology have given rise to a new generation of workhorse, vertically coupled, in-house automatic movements boasting superior performance. And lastly, there are the novel, highly progressive chronographs with varying degrees of technical innovation centered on the most fundamental aspects of a chronograph mechanism, from developing an improved coupling system, to isolating the chronograph mechanism completely, to reinventing the entire layout of the chronograph.

These three different categories of chronograph movements — each governed by its own set of tenets — stand in stark contrast to the two-dimensional ébauche movements of the past and are no doubt a sharp reflection of the state of watchmaking as a whole.

The Game-Changers That Defined the Horological High-End

If there was one watch that divided time into the period before it was launched and the period after, it would be the A. Lange & Söhne Datograph. The launch of the watch in 1999 was a point of inflection that repositioned the complication, raised the standard for the concept of “in-house”, and blazed a trail that would be crucial to the success of the industry. It pointed rivals the way forward, and together, these watches defined the great summits of watchmaking achievement.

The Datograph was the first in-house chronograph designed and built from the ground up in over two decades. In fact, till this day, it remains the benchmark against which all in-house haute horlogerie chronographs are measured, in terms of movement architecture, decoration and also engineering.

The Lange Datograph caliber 951.1

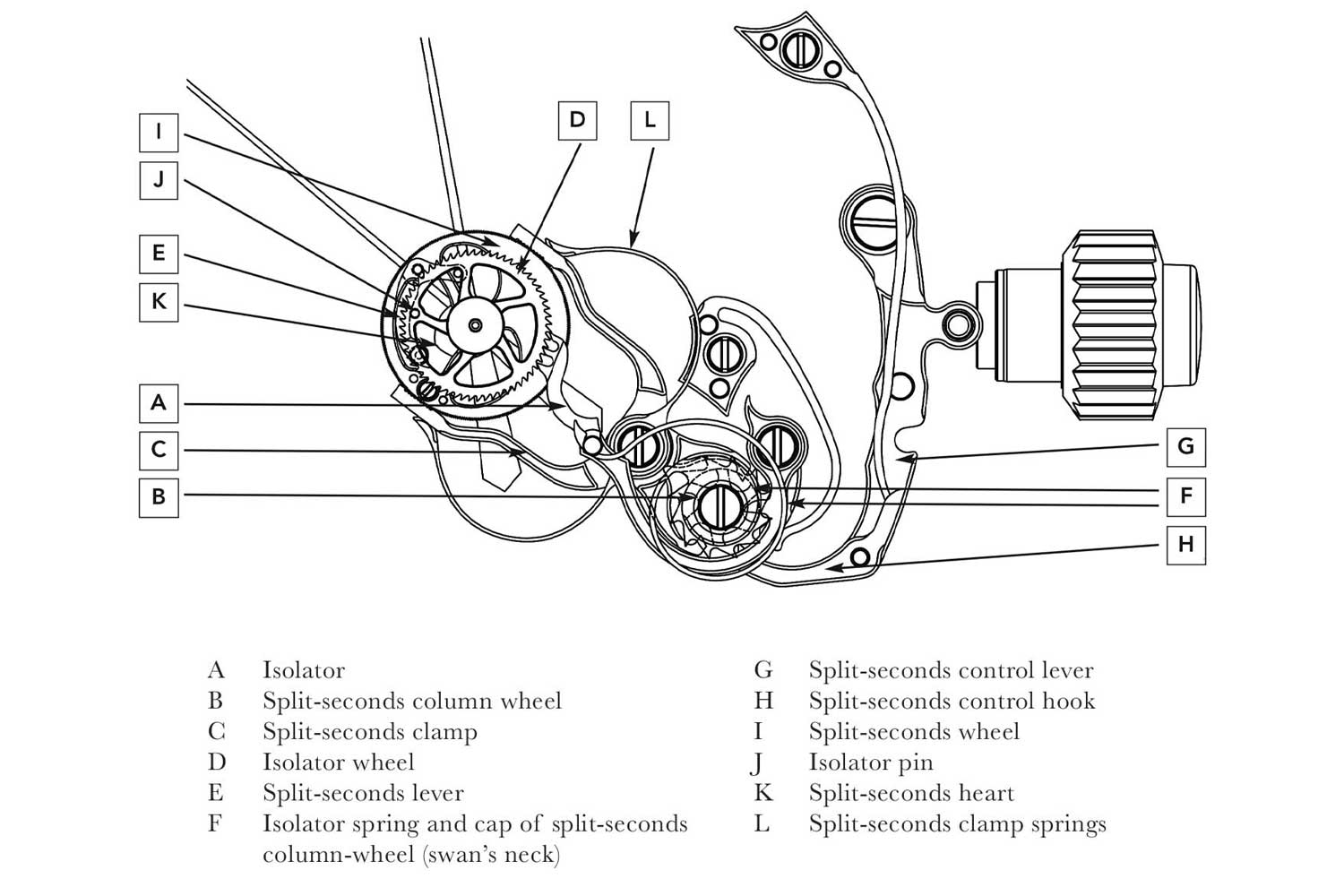

Just five years later, A. Lange & Söhne would throw a second curveball with the Double Split, bearing in mind that both Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin had yet to produce their own in-house chronographs at that time. The Double Split featured not just split seconds hands, but also split minute hands, enabling it to record twin elapsed times up to 30 minutes — a feat of watchmaking that is still unrivalled by any of its ilk.

A. Lange & Söhne Double Split with both split seconds and split minute hands, allowing the measurement of twin elapsed times up to 30 minutes.

Furthermore, both pairs of chronograph and rattrapante hands are flyback hands. When the pusher is depressed, the zero-reset lever presses a separate claw-shaped flyback lever, which in turn presses the clutch wheel and disengages it from the chronograph wheel. In the same motion, the reset lever then pushes the cams and the hands fly back to zero. Once the pusher is released, the lever is then released, and a spring then pushes the chronograph clutch to engage the chronograph seconds once again. The Double Split essentially incorporates two of this.

Finally, in 2005, Patek Philippe introduced its first fully in-house chronograph, the monopusher rattrapante ref. 5959P with the CHR 27-525 PS caliber. In contrast to the Datograph and Double Split, the 5959P is magnificently compact with a diameter of just 33mm as it was modelled on a wristwatch from 1923 with a Victorin Piguet ébauche.

The Patek Philippe ref. 5959P (Image: ACollectedMan.com)

In 2010, Patek Philippe unveiled the ref. 5170J, a classic in-house hand-wound chronograph with the CH 29-535 PS caliber inside that made its debut in the brand’s first ladies’ chronograph a year earlier. Apart from the standard features that are characteristic of Patek chronographs, the caliber also boasts several notable patents that improve reliability and performance.

Patek Philippe ref. 5170J (Image: ACollectedMan.com)

The slot on the snail cam ensures that the hook of the lever will not land harshly on the cam as it rotates, resulting in less friction. At the same time, the spring powers the chronograph minute lever, ensuring it exerts less tension and ratchets smoothly.

Visible on the left is the spring for the instantaneous minutes

The Patek Philippe CH 29-535 PS

The Patek Philippe CH 29-535 PS Q

Split-Seconds Mechanism on the 5204P

That same year, Vacheron Constantin celebrated its 260th anniversary with the introduction of not one but three in-house chronograph movements in the Harmony collection — the Harmony Monopusher cal. 3300, the automatic Harmony Ultra-Thin Grande Complication Chronograph cal. 3500 and the Harmony Tourbillon Chronograph cal. 3200.

The Vacheron Constantin cal. 3300 with a clutch wheel that is made of two stacked wheels that are driven by friction.

At a cursory glance, they all appear to utilize a classic horizontal coupling system. However, the clutch wheel is actually made up of two stacked wheels — a gold-coloured wheel on top of a steel wheel with spokes that form the shape of a Maltese cross. The gold-coloured wheel is in constant contact with the drive wheel while the steel wheel with much finer teeth engages the chronograph seconds wheel in the middle when the chronograph is engaged. Both wheels are friction-coupled much like a vertical clutch, slipping when the chronograph is activated. This is to eliminate any unwanted jitters when the chronograph starts.

In addition, the setup of having two stacked wheels also allows the upper gold-coloured wheel to have a more conventional tooth profile for optimal power transmission while the wheel at the bottom features finer teeth, typical of horizontal clutches. This innovation is also remarkable in that it does not alter the traditional layout of a horizontally coupled mechanism.

The most interesting movement of the three is the cal. 3500 in the Harmony Ultra-Thin Grande Complication Chronograph. At just 5.2mm high, it is the slimmest split seconds chronograph movement on the market, beating the CHR 27-525 PS in the ref. 5959 by 0.05mm. The beautifully constructed movement has been reintroduced this year in the newly launched Traditionnelle Split-Seconds Chronograph Collection Excellence Platine.

The cal. 3500 in the Vacheron Constantin Harmony Ultra-Thin Grande Complication Chronograph

The Modern, High Performance Automatics

Meanwhile, creating a modern automatic chronograph became top priority for many brands. Crucial to the development of this category of chronographs was the Swatch Group’s intention to restrict movement and parts supply to third parties in the 2000s. At that time, more than half of Switzerland’s movements were produced by its subsidiary ETA while another subsidiary Nivarox was the industry’s key supplier of hairsprings.

Put simply, everyone scrambled to find or build an alternative to the Valjoux 7750. And on a more fundamental level, this period also saw the development of many alternative hairsprings.

Precision Engineering, the sister company of H. Moser & Cie., and Atokalpa, the sister company of Vaucher and Parmigiani, as well as Richemont-owned brands, A. Lange & Söhne, Montblanc and Jaeger-LeCoultre went ahead and developed their own hairspring competencies. At the same time, the Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM) backed by industry giants Rolex, Patek Philippe and the Swatch Group introduced a material that would mark a giant leap forward, not just in terms of hairspring technology but also escapements — silicon. Being a third the density of steel, silicon along with MEMs technology including deep reactive-ion etching (DRIE) as well as Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung (LIGA) processes would prove particularly useful to achieving new heights of performance in chronographs later on.

Ultimately, the beauty of this segment of automatic chronographs lies in their smart design and their incredibly measured engineering to ensure accuracy, efficiency, robustness and serviceability. On top of that, most of these calibers are continuously improved upon from their introduction, enabling them to stay in production for years on end. This itself is a rather noble pursuit that eclipses hand-finishing in significance.

The Rolex cal. 4130 movement launched in 2000 in the Daytona ref. 116520 did for modern automatic chronographs what the Datograph did for haute horlogerie hand-wound chronographs. Boasting refinement and performance in equal measure, it became a benchmark against which all automatic chronographs are measured. Equipped with a column wheel and vertical clutch, the movement is impressively compact with a staggeringly low parts count of 201.

In contrast to the Rolex cal. 4030 which was based on the El Primero with a horizontal clutch, the 4130 utilizes a technically superior vertical coupling system. Though by the new millennium, vertical clutches were pretty much already at the forefront of chronograph design, it was Rolex who delivered a technically cohesive movement in terms of both the chronograph mechanism as well as the timekeeping half of the movement.

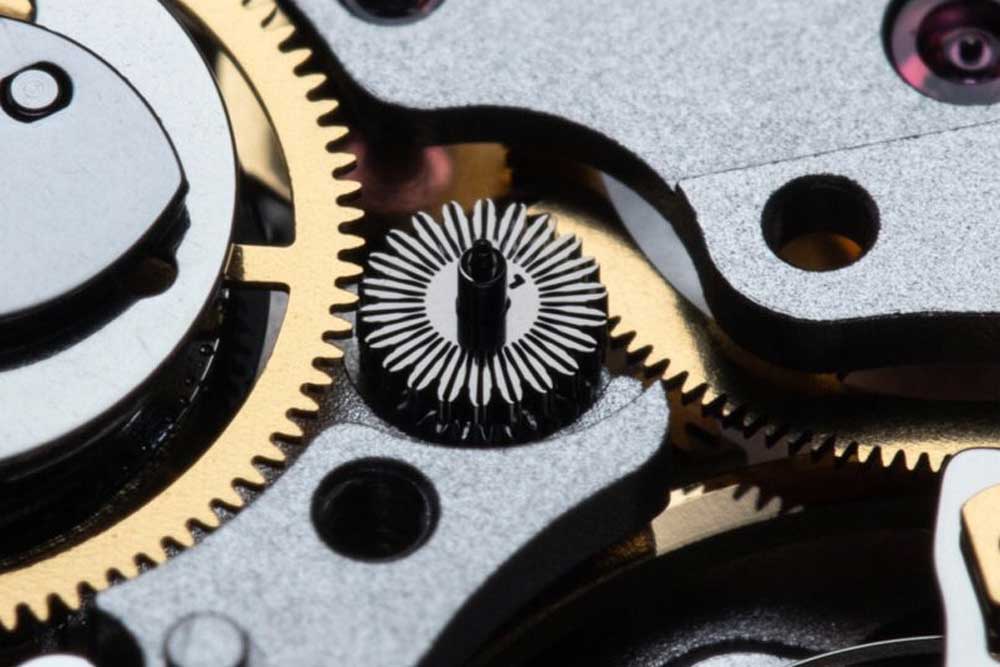

The Rolex Daytona 4130 Calibre

This layout is similar to the later Breitling B01 movement as well as the newly launched Audemars Piguet cal. 4401 in that the fourth wheel is not integrated in the vertical clutch assembly so as to free up space in the middle. As a result of this construction, an additional set of wheels is needed to drive the vertical clutch which in turn drives the chronograph seconds wheel. This solution, however, presents a new set of challenges as extra wheels would also mean more play between the teeth as they mesh, which can potentially result in chronograph seconds hand stutter — a problem vertical clutches, by their very nature, were designed to eliminate. To solve this, Rolex utilizes a uniquely shaped seconds wheel with sprung teeth fabricated using MEMS technology, specifically LIGA. This removes all play between the wheels due to the deep penetration between teeth.

To reduce the play between wheels, Rolex incorporates a uniquely shaped seconds wheel fabricated using LIGA technology.

In 2004, Jaeger-LeCoultre introduced the in-house cal. 751, a slim, column wheel, vertically coupled chronograph movement that was inspired by the construction of the superb Frédéric Piguet 1185. In fact, it can be considered an improved version of the latter. The base movement uses a similar layout to the 1185 in that the fourth wheel of the movement is located at six o’clock, which is connected to the running seconds hand on the dial.

The ultra-thin Jaeger-LeCoultre cal. 751

The cal. 751, however, is superior in performance to the standard Frédéric Piguet 1185. It boasts two serially coupled barrels to ensure a more even torque over the course of its power reserve. Together, they offer 65 hours of power reserve versus 40 hours on a single barrel in the Frédéric Piguet. But the real feat lies in having nearly identical dimensions to the Frédéric Piguet 1185, which is to say, it is impressively compact and slim for what it packs. It measures just 25.6mm wide and 5.7mm high.

Additionally, the movement operates at a frequency of 4Hz, enabling the measurement of time down to the nearest eighth of a second while the 1185 runs at a more traditional frequency of 3Hz. Today, the 1185 in the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Chronograph still has the same power reserve and frequency while Blancpain’s version of the 1185 has benefitted from silicon technology, achieving a power reserve of 50 hours. All in, the Jaeger-LeCoultre cal. 751 still comes out on top. Lastly, it also features an extremely compact and robust ratchet wheel-and-pawl winding mechanism.

The next Richemont brand to launch its own automatic chronograph was IWC. In 2007, the brand unveiled the cal. 89360 in the Da Vinci Chronograph. The watch features a rather unusual layout in which the counters are laid out vertically on the dial with a co-axial hour and minute counter at 12 o’clock, enabling elapsed hours and minutes to be read off the dial directly. It relies on an oscillating pinion to connect the fourth wheel of the movement to the chronograph seconds wheel while the hour and minutes counter is driven directly by the barrel by way of a second pinion. This configuration effectively reduces the load on the going train as power is drawn directly from its source. At the same time, the chronograph seconds wheel is designed with a special teeth profile to minimize the initial hiccup of the seconds hand when the chronograph is activated.

The cal. 89360 as seen in the IWC Da Vinci Chronograph.

To start off, it features a tri-compax layout with the seconds counter at nine o’clock that is directly driven by the going train. This allows the entire chronograph mechanism to be designed as a single unit, which can be conveniently removed during servicing, as opposed to integrating the fourth wheel in the vertical clutch assembly in the middle. However, having an indirectly driven vertical clutch, as mentioned previously, creates the problem of backlash, caused by gaps between meshing teeth. While the Rolex 4130 solved this with a LIGA seconds wheel, the B01 utilizes a tiny LIGA intermediate pinion between the fourth wheel and the chronograph seconds in the middle. This effectively enables full surface contact between teeth during meshing, thereby eliminating play.

The B01 utilizes a tiny LIGA intermediate pinion that connects the fourth wheel to the chronograph seconds in the middle, eliminating play. (Image: TheNakedWatchmmaker.com)

The B01 caliber has a diameter of 30mm and a height of 7.2mm, making it 0.7mm thicker than the 4130. It offers a power reserve of 70 hours and has a frequency of 4Hz. Notably, Tudor’s implementation features a silicon hairspring as well as a free sprung balance wheel, making it the more advanced version of an already impressively constructed movement.

In 2011, Omega finally launched its first in-house automatic chronograph movement, the cal. 9300. There are several unusual features in this movement that distinguish it from other chronographs on the market. It has a co-axial hour and minute counter at three o’clock on the dial, and it also features an indirectly driven running seconds, both of which contribute to its height of 7.6mm.

The Speedmaster Grey Side Of The Moon "Meteorite" powered by the calibre 9300 with a co-axial hour and minute counter at three o'clock.

Secondly, the Omega 9300 is equipped with double barrels coupled in series to ensure a more even flow of power. The first barrel contains a manual mainspring while the second is fitted with an automatic mainspring. Once the first barrel is fully wound, the second starts winding before it slips to prevent damage from overwinding. As the watch runs, the second barrel unwinds and once its stored energy becomes equal to the amount in the manual barrel, both barrels will begin releasing energy simultaneously, equalizing torque feed.

The Omega 9300 with a directly driven vertical clutch. As the movement uses a co-axial escapement, which has fewer teeth, the gear train comprises four wheels instead of three.

The co-axial escapement was designed to combine the locking and unlocking system of the Swiss lever and the direct impulse of the detent while eliminating both their shortcomings primarily sliding friction as well as poor shock resistance. It requires little to no lubrication and results in greater accuracy over time and longer service intervals.

In 2016, the 9300 movement was eventually replaced by the 9900 which is a METAS-certified Master Chronometer. An initiative started by Omega and the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology (METAS), the Master Chronometer certification adds tangible value to a watch as it tests finished watches comprehensively for not just timekeeping but also functionality. At the same time, the co-axial escapement is made from proprietary alloys that boost magnetism resistance to over 15,000 Gauss, a level that remains unrivalled on market.

The Progressive Chronographs

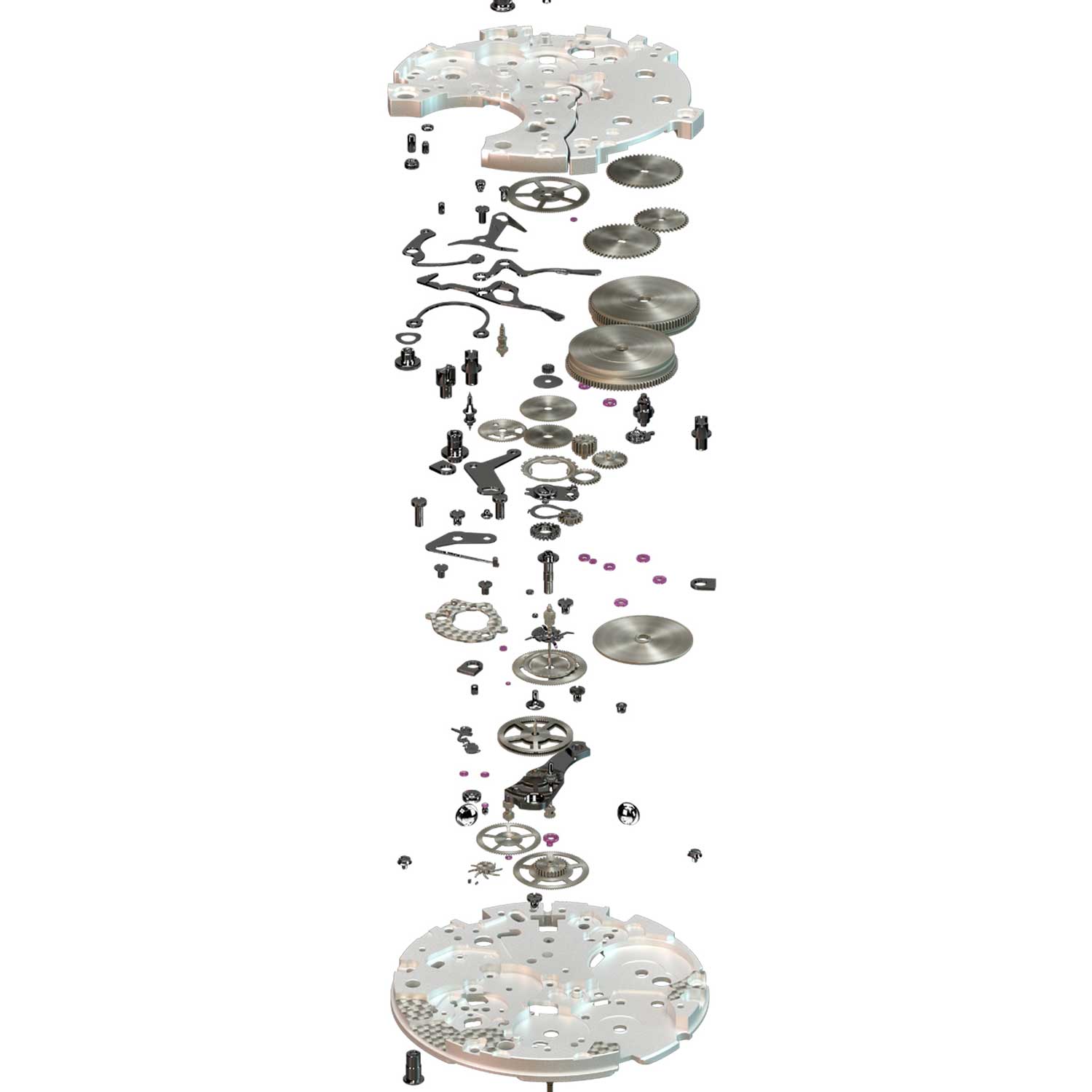

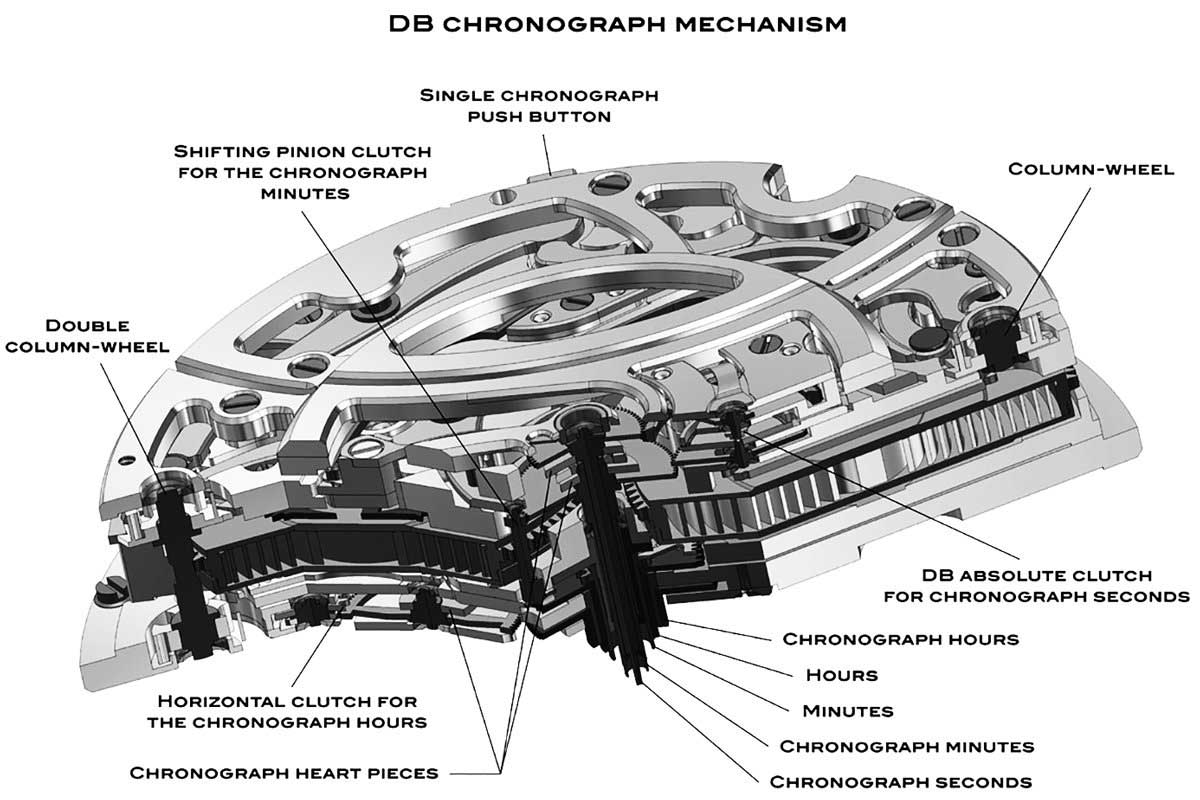

The year 2006 saw the introduction of two kinds of chronographs that would turn watchmaking on its head. The first — and also one of the most revolutionary chronographs in all of watchmaking — is the De Bethune Maxichrono as it upended the conventional design of a chronograph. The prototype was improved upon before the production model made its debut in 2014.

The Maxichrono dispensed with the traditional tri-compax layout of the complication, and was instead designed with three concentric scales, five centrally mounted hands and a single pusher.

The revolutionary DB28 Maxichrono with three concentric scales and five centrally mounted hands

The Absolute Clutch is made up of a pair of face gears that mate like a horizontal clutch, but vertically. Like a horizontal clutch, the clutch and the chronograph wheel are only engaged when the chronograph is activated, essentially eliminating the main disadvantage of the vertical clutch — the friction generated when the chronograph is not in use.

The entire "island" bridge here is actually the Absolute Clutch that lowers when the chronograph is activated.

This is further accompanied by a silicon escape wheel, which reduces inertia and operates with minimal friction. The balance wheel is in titanium with white gold inserts to increase mass and operates at a high frequency of 5Hz. It is held in place by a flat and short balance bridge for sturdy support and is attached to a hairspring that is distinguished by a patented architecture. In contrast to the Breguet overcoil, which is delicate as it is high and vulnerable to shocks, the De Bethune hairspring is flat with a wider terminal curve, which reduces its height while improving concentricity with respect to gravity. The escapement has a modular design which enables it to be replaced by a tourbillon variant as seen in the Maxichrono Tourbillon DB29.

The next watch was the F.P. Journe Centigraphe Souverain, a foudroyante chronograph that, in theory, manages to measure time down to 1/100th of a second even though it runs on a 3Hz escapement.

F.P. Journe Centigraphe Souverain (Image: ACollectedMan.com)

Importantly, it was the first watch that departed from the traditional construction of the chronograph in which the chronograph mechanism is dependent on and draws power from the gear train of the movement.

The highly innovative clutch-less cal. 1506 in the Centigraphe Souverain with a mainspring barrel that unwinds in two separate directions (Image: ACollectedMan.com)

In the years that followed, watchmakers would push the idea of isolating the chronograph further, developing various highly unique solutions that did away with coupling systems and their associated drawbacks.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre Duomètre à Chronographe of 2007 featured two separate barrels and gear trains that shared one escapement and one balance wheel. In this setup, the regular timekeeping gear train drives the escape wheel pinion while the chronograph train directly engages the escape wheel.

The Duomètre à Chronographe caliber 380 with no coupling system. Instead, the gear train drives the pinion of the escape wheel while the chronograph gear train engages the escape wheel directly.

The highly innovative Breguet Tradition Chronograph 7077 with two oscillators, gear trains and sources of power.

While the timekeeping escapement runs at a frequency of 5Hz, the escapement for the chronograph operates at 50Hz, making them true hundredth-of-a-second chronographs. To reduce inertia and wear, the pallet fork and escape wheel are both made of silicon which offers excellent friction resistance and energy saving, both of which help deliver a higher frequency while minimizing the effects of wear.

2017 also saw the launch of the Montblanc TimeWalker 1000 Limited Edition which, interestingly, combined two solutions discussed above to display both a hundredth of a second and a thousandth of second. Like the Defy 21, the chronograph is powered by its own barrel, gear train and oscillator. It runs at a high frequency of 50Hz, enabling a true 1/100th of a second resolution, while the timekeeping oscillator operates at a more traditional frequency of 2.5Hz.

The Montblanc Timewalker 1000 Limited Edition that displays both 1/100th as well as 1/1000th of a second.

Meanwhile, Fabergé debuted the Visionnaire Chronograph with a radically new central chronograph movement developed by Agenhor, the Geneva-based complications specialist led by Jean-Marc Wiederrecht, one of the finest minds in watchmaking. Dubbed the AgenGraphe, the automatic chronograph broke free from the standard mould quite completely, both in terms of the dial layout as well as movement architecture.

Instead of mounting all hands on the central axis like the Maxichrono, the AgenGraphe features a more intuitive layout in which the chronograph is given pride of place in the middle, allowing the user to read elapsed time off the dial. The hours and minutes are instead indicated along the outermost circumference of the dial.

The Fabergé Visionnaire chronograph equipped with the revolutionary movement by Agenhor

The uniquely constructed AgenGraphe chronograph mechanism is visible in the middle of the movement while the gear train is built around it.

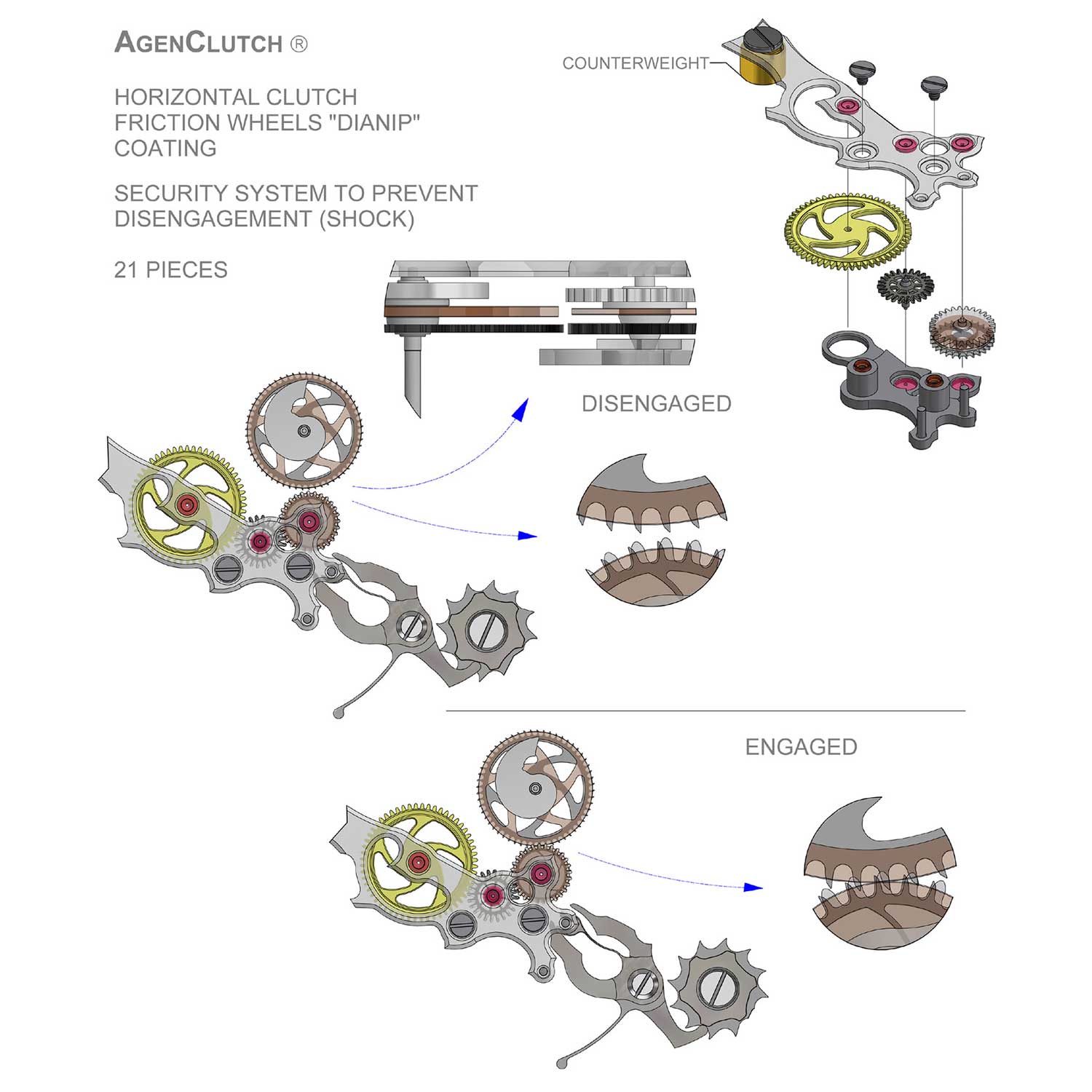

Instead of a regular toothed wheel, it relies on toothless wheels coated with a diamond nickel composite that engage through surface friction. In the event of shock, a tulip-shaped spring allows the wheels to safely move apart, but they stay in alignment relative to each other thanks to a secondary, co-axial toothed wheel. The teeth on the secondary wheel, however, are exceptionally fine, ensuring that a shock that displaces the diamond-coated wheels will incur a maximum error of 0.33 seconds in the chronograph measurement.

The patented AgenClutch system (Image: Singer)

This highly inventive movement would later be used in the Singer Reimagined Chronograph as well as the Moser Streamliner Flyback Chronograph, each with its own respective modifications.

While slenderness is rarely a horological anchor when it comes to constructing a chronograph, due to the inevitable stacking involved and the inherent difficulty in delivering good performance as a watch gets thinner, Bvlgari has charged against the grain, launching two ultra-thin automatic chronograph movements in last two years.

The Octo Finissimo Chronograph GMT Automatic

The ultra-thin cal. BVL 318 with a classically solid construction

The BVL 318 caliber's peripheral rotor allows for the beautiful movement to remain visible from the caseback

The Bvlgari Octo Finissimo Tourbillon Chronograph Skeleton Automatic

Visible at 6 o'clock, a boomerang-shaped clutch lever with an oscillating pinion connects the tourbillon cage to the chronograph seconds wheel in the middle.

A Mirror for Our Times

As with any other complication such as the tourbillon and minute repeater, the chronograph has undergone many incremental yet fundamental changes over time that reflect the changing landscape of watchmaking.

That technological shifts ushered in identity changes in a chronograph from an instrument to a luxury product — as exemplified by the emergence of various sub-categories of chronographs such as the haute horlogerie, the ultra-thin and the high-frequency — is perhaps less of a surprise. What is a surprise, however, is the potent reinvention of the chronograph such as the AgenGraphe and Maxichrono, as well as the creative destruction within these sub-categories such as the high-frequency Breguet Tradition Chronograph 7077 and the Zenith Defy 21.

At the same time, the sheer breadth of work that has been devoted to solving the most fundamental issues of a chronograph, namely seconds-hand stutter and amplitude loss, is simply astounding. And it suffices to say that the inherent restrictions in the display and architecture of a chronograph have in turn permitted variations on multiple levels, making it inargurably one of the most fascinating and popular types of timepieces today.