The Striking Genius of Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike

Editorial

The Striking Genius of Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike

When Chopard unveiled its first in-house movement — the L.U.C Caliber 1.96 — in 1996, it did more than inaugurate a new manufacture in Fleurier. It marked a decisive shift in the brand’s identity, transforming a house best known for “Happy Diamonds” into one founded on the highest expressions of horological craft. With that single movement, Chopard signaled that it intended not merely to participate in the world of high watchmaking, but to stand alongside its most revered names. The L.U.C collection, named for founder Louis-Ulysse Chopard, became the vessel for that transformation, a platform on which the brand would steadily build a vocabulary of serious watchmaking, from tourbillons and perpetual calendars to chronographs and, ultimately, to the most demanding of all complications – the chiming watch.

Its journey through the realm of chiming complications has followed a steady arc that reflects both the evolution of the manufacture and the deepening of its technical ambition. It is a discipline that simply does not yield easily to newcomers. The knowledge required to create a chiming watch is cumulative, built over decades of patient trial, refinement and intimate familiarity with the invisible nuances of sound, power and motion. Without the long continuity of experience, it is almost impossible to bring such a mechanism to life within the walls of a manufacture. That Chopard has built, from the ground up, the intellectual, technical and practical foundation required to create such mechanisms is, in itself, a rare achievement in modern watchmaking.

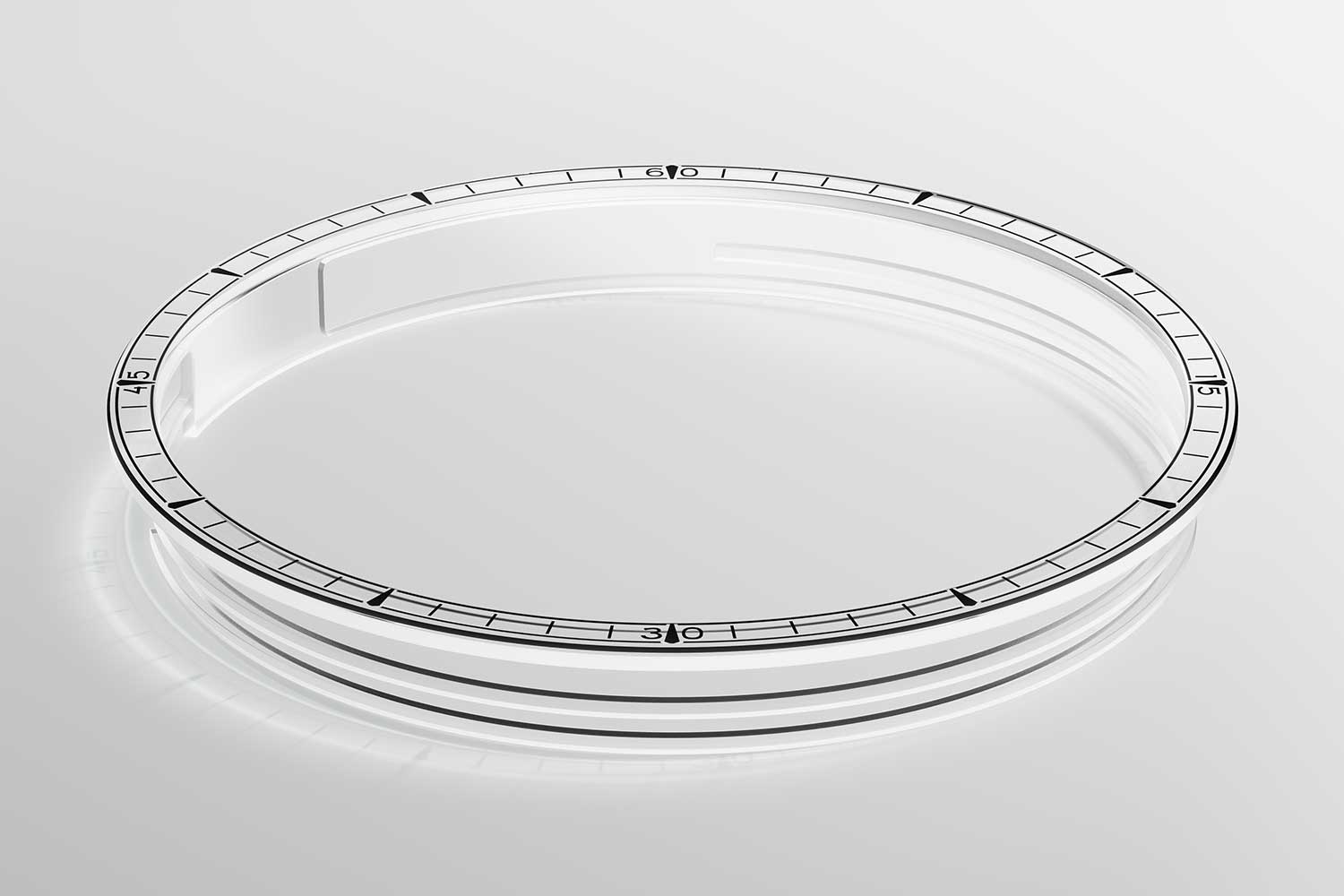

The journey began in 2006 with the L.U.C Strike One, a passing strike that sounds a single note at the top of each hour on traditional metal gongs, and reached a new level of sophistication a decade later with the L.U.C Full Strike, a full minute repeater that earned the Aiguille d’Or at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG) for its innovative use of sapphire gongs cut from the same block as the crystal, giving the chimes both exceptional clarity and resonance. In 2022, the manufacture unveiled the L.U.C Full Strike Tourbillon, combining its award-winning acoustic system with a tourbillon regulator. Now, 20 years after its first chiming watch and three decades on from the movement that started it all, that journey has culminated in the L.U.C Grand Strike, which confronts the most complex and demanding of all horological achievements – the grande sonnerie.

2006: Chopard L.U.C Strike One in pink gold, its first hour striker and a statement of intent that it would pursue the lofty goal of the minute repeater

2016: Chopard L.U.C Full Strike is launched and earned the Aiguille d’Or at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG)

To understand the scale of what Chopard has achieved, it is worth considering why chiming complications have always stood apart in the landscape of watchmaking. Their outward action seems simple enough as hammers fall in turn upon their gongs, yet behind this lies the most complex of mechanisms in watchmaking. The minute repeater, which on demand strikes the hours, quarters and minutes, is the most familiar expression of this art. The difficulty lies not only in the multitude of parts within the strike works and strike train, but in the way they must behave together. Every component depends upon the next, and the smallest fault in form or proportion is enough to silence the whole. The order of assembly and the precision of each fit are critical. Even a slight irregularity in a pivot, spring strength or lever shape can cause the mechanism to misfire or jam. Great skill is required in adjusting positions, depths and tensions of the various parts, while the quality of the chime itself also rests on a host of other factors such as the shaping and tuning of the gongs, the force with which the hammers strike them, and the character of the case in which the movement sits. Design, material and size of the case all shape the final sound.

From this foundation rises the grande sonnerie, which extends the challenge in every direction. A grande sonnerie automatically strikes the hours on the hour, and both the hours and quarters at each quarter. In petite sonnerie mode, it only strikes the hours on the hour and the quarters at each quarter, while retaining the ability to strike a full sequence down to the minute on demand. The system of racks, snails and strike train is the same, but it no longer suffices. Auxiliary devices must be introduced to govern the flow of power and decide when the chimes occur. An automatic release mechanism ensures the sonnerie sounds of its own accord; a suppressor governs the petite sonnerie when only the quarters are struck; a manual release preserves the repeater function; and finally, a silencer grants the wearer discretion. Each of these devices must not only work but work together without disturbing the fragile sequence already in place.

The result is a mechanism of forbidding intricacy. It is a dense order of interlocking causes and effects. For this reason, the grande sonnerie has long been regarded as the summit of horology. Each sub-mechanism interacts with others in ways that must be understood through repeated trial, observation and correction. There is no shortcut. The mastery of it is the product of long study, practice and even longer patience.

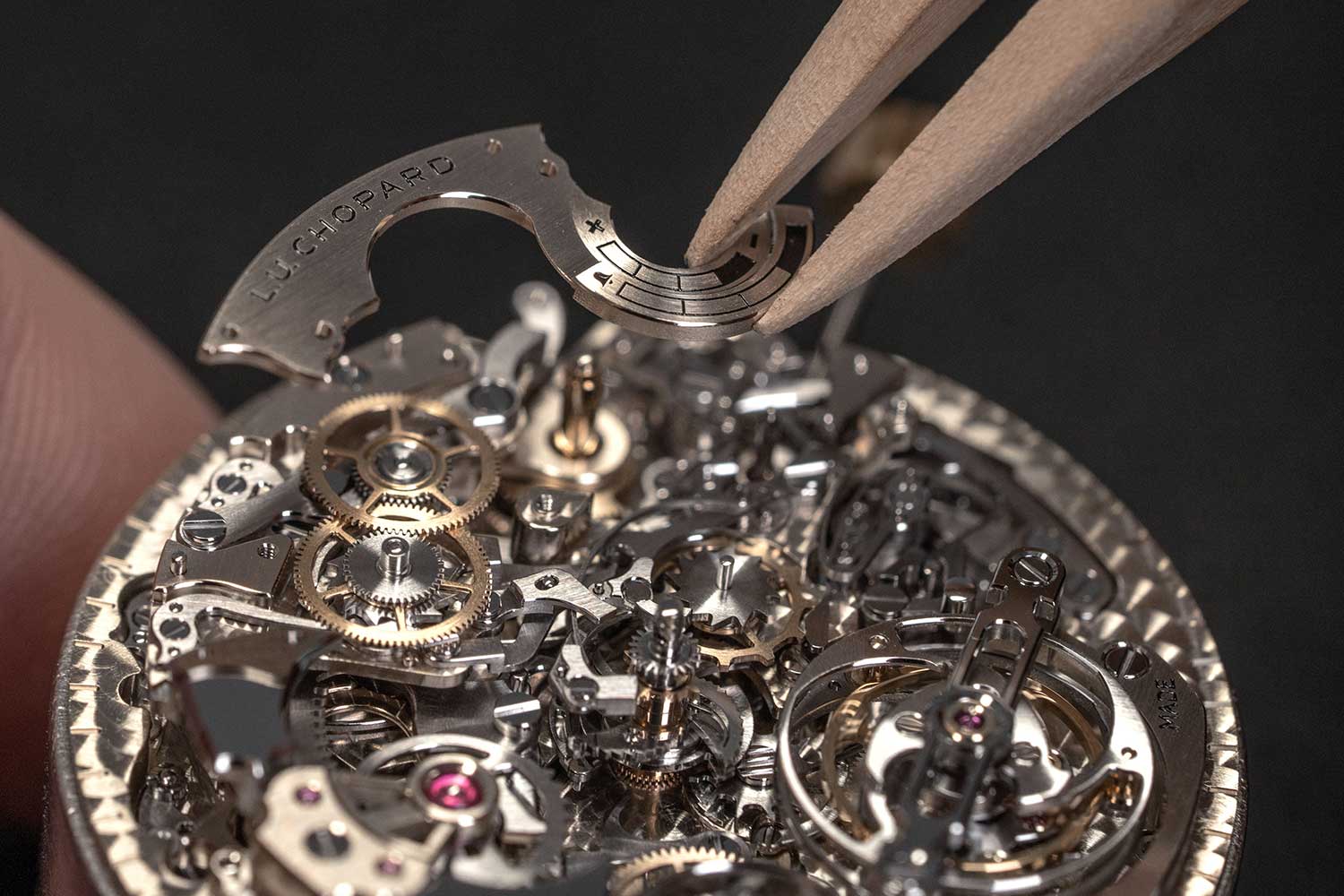

The scale of Chopard’s latest work reflects the magnitude of the task. The Caliber L.U.C 08.03-L in the Grand Strike, which also includes a tourbillon, comprises a staggering 686 parts, compared to 568 in the Full Strike Tourbillon. Such a work admits no compromise. It is the highest expression of watchmaking because it gathers into one mechanism the principles of construction, the demands of acoustics and the discipline of proportion, adjustment and tuning. But further still, as with the L.U.C Full Strike, the Grand Strike bears witness to a host of innovations. No fewer than five patents have been secured for its construction, while another five, first introduced in the Full Strike, were carried forward.

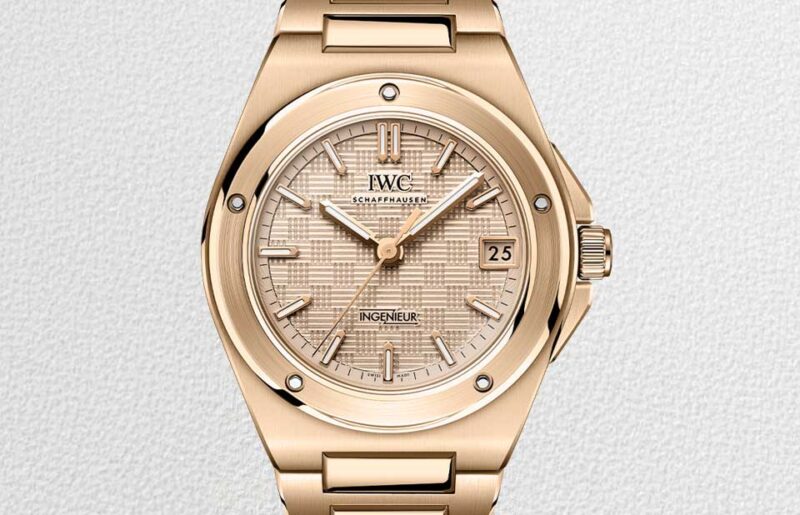

In fact, almost 11,000 hours were invested in the project, of which 2,500 hours were spent fine-tuning the prototype. The watch has an 18K ethical white gold case that measures a 43mm across and 14.08mm in height. The dial has been reduced to a minute track which is directly printed on the sapphire crystal and, due to the construction of the Caliber L.U.C 08.03-L, the most interesting and crucial parts of the chiming mechanism are fully visible. A discreet selector beside the crown allows the choice of grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie or silence. The strike barrel is wound by the crown while the push-piece set within the crown serves to activate the minute repeater.

When fully wound, the strike barrel is able to deliver 12 hours of continuous chiming in the grande sonnerie mode. Turning the crown clockwise winds the main timekeeping barrel and counterclockwise, the strike barrel. As with the Full Strike, this is made possible by a reverser — a co-axial three-wheel module with one bidirectional input and two unidirectional outputs. When the crown is turned, its rotation is transmitted through the input wheel equipped with unidirectional pawls on each face, allowing energy to be directed according to the direction of rotation. Turning the crown clockwise engages the upper set of pawls, transmitting energy through a train of wheels to wind the going barrel. Turning it counterclockwise engages the lower pawls, which in turn drive the striking barrel. The disengaged pawls simply click over their respective ratchet teeth, allowing each train to remain stationary when the other is being wound. The power reserves of both the main timekeeping barrel and sonnerie are displayed concentrically at 2 o’clock.

The Strike Works

It must be noted that in the L.U.C Full Strike, and now in the Grand Strike, the strike works are conceived in a manner that departs from the basic template of the minute repeater that has persisted for more than a century. This alone is remarkable, as minute repeaters and grande sonneries are rare enough by nature. They demand so much care and skill that few watchmakers ever attempt them and, when they do, sticking to proven methods is simply good sense. Innovations in case construction, gongs and hammers appear from time to time, yet innovations that reach into the strike works themselves have tended to be even more uncommon.

The strike works, properly so called, are those parts situated beneath the dial which unite the chiming mechanism with the main going train of the watch. It is through them that the time displayed on the hands is translated into sound. They comprise the assemblies by which the hours, quarters and minutes are commanded to strike and without their ordered action, no chime can be produced. Specifically, the quarter and minute snails are fixed directly to the shank of the cannon pinion, so that the reading of the time for the chiming mechanism is immediate and direct. At each turn of the cannon pinion, a pin on the quarter snail advances the tooth of a 12-hour star wheel that is fixed to an hour snail. The quarter, minute and hour snails control the travel of their respective racks.

Traditionally, the hammer pallets are lifted by large, sector-shaped racks whose travel defines the number of blows. The first hammer is actuated first by a pallet engaged by the hour rack, then by a second pallet engaged by the quarter rack to deliver the first note of each quarter. The second hammer is similarly actuated by one pallet operated by the quarter rack for the second note of each quarter, and another operated by the minute rack for the final minute strikes. This layered system of overlapping racks has dictated the familiar layout of repeaters for generations.

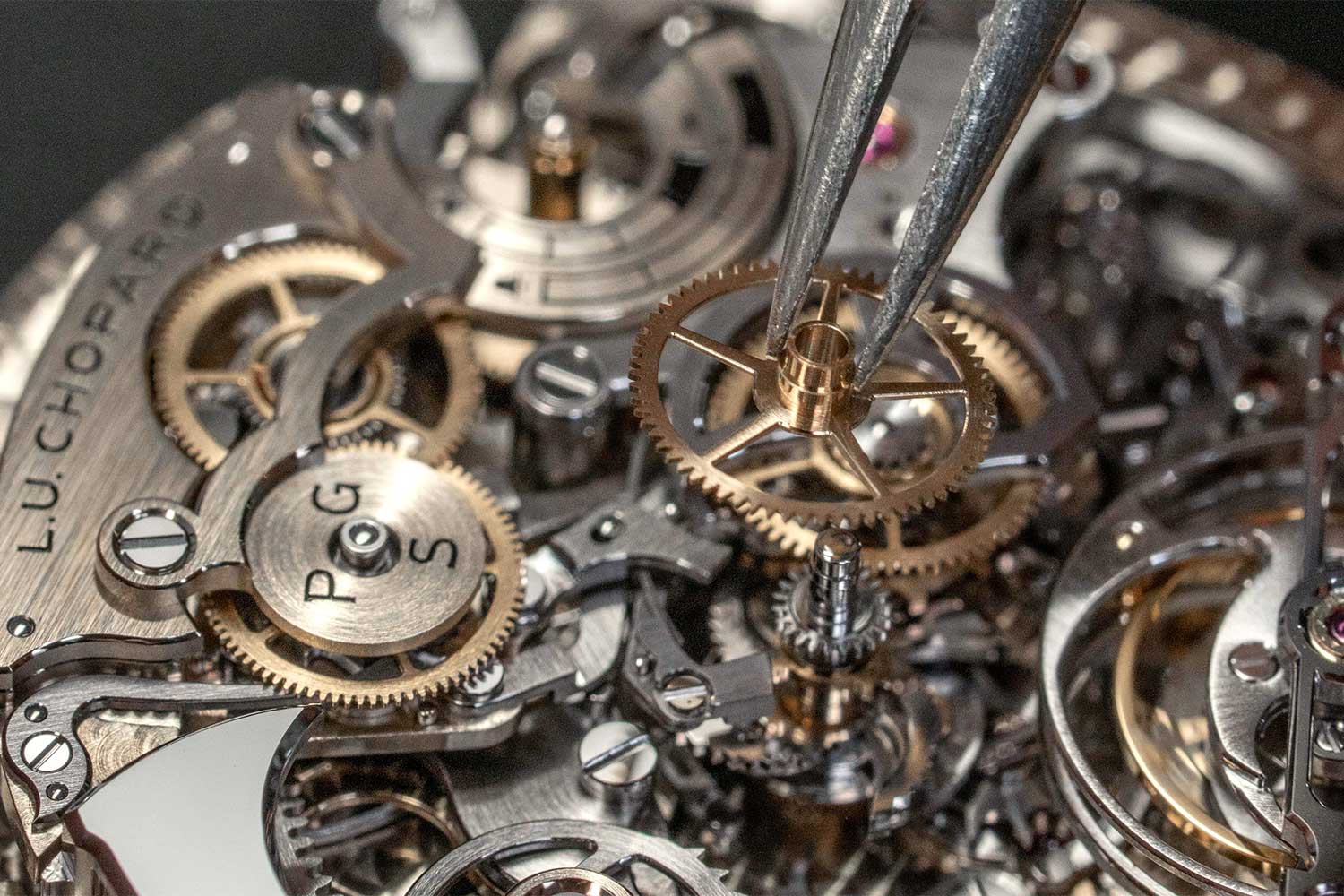

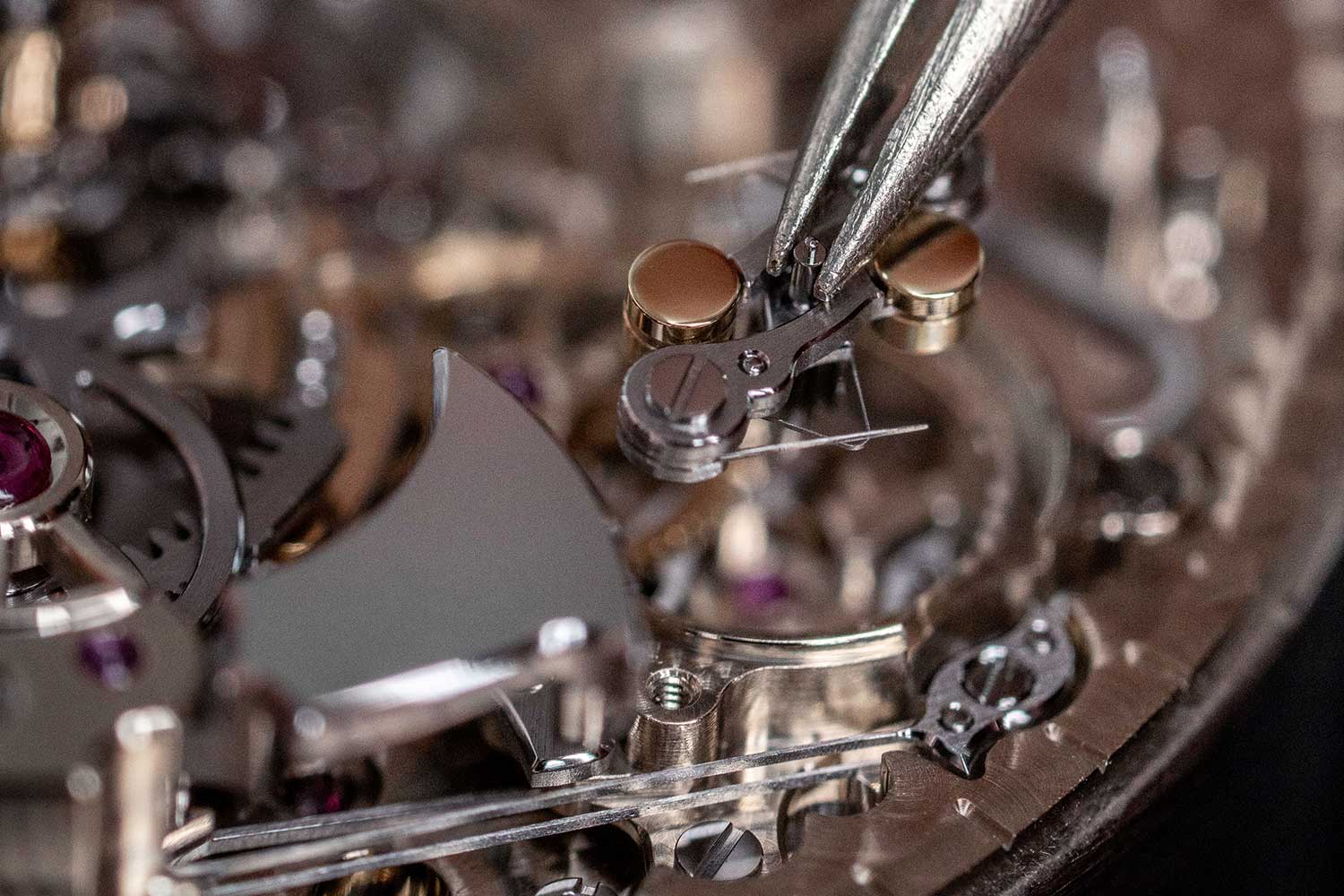

In the Full Strike and Grand Strike, the racks no longer act directly on the pallets. Their role is reduced to a brief act of sampling, while the actual work of lifting the hammers is performed by three co-axial striking wheels — hour, quarter and minute ratchets — mounted on a single arbor and driven by the strike train. The hour ratchet carries 12 teeth on its periphery for the hours; the quarter ratchet bears two sets of three teeth, alternating between the two hammers to produce the double “ding-dong” motif of the quarters; and the minute ratchet has 14 teeth to mark 1 to 14 minutes following the last quarter. Each ratchet is rigidly paired to its own pinion, and each pinion meshes with its rack. During the sampling phase, each ratchet is back-driven by its respective spring-loaded rack through a pinion. The racks pivot against their snails through short arcs.

As in the Full Strike, the pallets in the Grand Strike are actuated by striking wheels, visible between the hammers, instead of the racks themselves

Once the racks have fallen, the strike train drives the arbor forward, turning the ratchets in the striking direction. Their teeth then engage the hammer pallets in turn, producing the measured sequence of notes.

At the same time, the ratchets are designed to eliminate the silent interval that is usually heard when no quarters are to be struck. In a traditional minute repeater, this silent interval arises because the hour and quarter racks are not directly connected. The hour rack is directly driven by the repeater barrel while the quarter rack receives motion only indirectly through a finger and pinion on the repeater barrel arbor, which produces delay. Further variation comes from the minute rack, whose hook bears upon the wide teeth — typically five or seven — of the quarter rack, so its position on their faces alters the interval.

In the Full Strike and Grand Strike, the hour and quarter ratchets are directly linked. The hour ratchet has an internal surface made up of four steps for 0 to 3 quarters. A hook with a drive pin pivoted on the quarter ratchet rests against this surface under spring tension. As the hour ratchet turns during striking, the pin rides along one of the steps, held there until the hour sequence is complete. At that moment, the geometry of the stepped surface forces the hook to pivot and the drive pin to shift position, transferring motion to the quarter ratchet, which begins striking immediately after the hours conclude, regardless of how many blows were required.

The result is an immediate, consistent hand-off, and the same logic carries through to the minutes. The quarter and minute racks, rather than their ratchets, are mechanically linked by a pawl that engages one of the 14 tooth gaps on the minute rack, ensuring that as soon as the quarters conclude, the minute rack is drawn to follow without pause. Together, the stepped hour-to-quarter coupling and the pawl-controlled quarter-to-minute draw remove the variable “dead time” of textbook repeaters and produce a continuous, measured cadence of hours, quarters and minutes.

The Strike Train

The strike train begins with the strike barrel, which holds the power for the chime. One of the main differences in a grande sonnerie and a minute repeater is how the strike barrel is wound and released. In a minute repeater, the strike barrel is wound only when the slide or push-piece is actuated; the user’s action winds the spring barrel via a rack, and upon release, the stored energy is immediately discharged to drive a single chiming sequence. By contrast, a grande sonnerie is built around a strike barrel that is kept charged manually by winding the crown, enabling it to chime the hours and quarters automatically in passing throughout the day.

One of the most critical parts in a grande sonnerie is the automatic release rocker, which is lifted every quarter by a star on the

cannon pinion

When the two are combined in a single watch, this apparent contradiction is reconciled by separating the functions of charging and releasing. The crown alone supplies energy to the strike barrel, while the repeater slide or push-piece does not wind the spring but merely trips a release device to let the barrel power the strike train. Thus, whether the mechanism is striking in passing as a sonnerie or on demand as a repeater, both draw from the same manually wound barrel. The interesting thing is that the L.U.C Full Strike was conceived this way from the outset. Its repeater barrel is wound manually via the crown, while the pusher serves to release the strike train. This architecture is fundamentally different from that of any standard repeater, making its evolution into a grande sonnerie far more natural.

From this barrel, energy flows through a train of wheels leading to the regulator, which governs the tempo of the hammers. There are two basic types of governors: the traditional anchor governor, which functions just like a lever escapement whereby an escape wheel is locked and unlocked by a pallet, and the centrifugal governor which is a fly with two arms that are weighted at their tips. Chopard chose the latter. As the governor rotates, the arms extend outwards against the force of a spring until their spring beaks come into contact with a fixed inner wall. The resulting friction slows the strike train until equilibrium is reached. In contrast to an anchor governor which makes a distinctive buzzing noise, a centrifugal governor is much quieter.

As the strike works are completely different from a traditional chiming watch, the train also differs slightly. In a traditional chiming watch, the hour rack is squared to the arbor of the strike barrel. An hour feeler attached to the winding rack rests against the hour snail, which dictates the rotation of the barrel and, consequently, the position of the hour rack. But in this scenario, the striking ratchets are carried on a separate staff, with the racks driving their respective pinions. As such, they are driven through the strike train. Hence, to allow the racks to sample their snails freely without fighting the forward torque of the barrel, the barrel must be temporarily decoupled.

Between the barrel and the staff that carries the ratchets is a clutch, whose job is to connect or disconnect the two. When engaged, torque from the barrel is transmitted through the wheels to the strike staff, turning the hour, quarter and minute ratchets that in turn lift their hammer pallets. Once lifted, the hammers fall back against the gongs in a sequence controlled by the regulator.

Before this striking can begin, however, the mechanism must first determine how many blows to sound. This sampling phase is carried out by the racks, each pulled by a spring to fall against its corresponding snail cam. As they pivot downwards, the racks drive the ratchets in reverse, setting them into positions that correspond to the number of hours, quarters and minutes to be struck. Decoupling the clutch at this stage remains essential. With the strike train disengaged, the forward torque of the barrel no longer resists the backward motion imposed by the racks, eliminating parasitic losses and avoiding any risk of blockage. In the latest design, the barrel is held stationary not by the clutch itself but by a dedicated blocking system acting directly on the strike train and regulator. This ensures that the stored energy in the barrel remains fully preserved until the moment the train is re-engaged and the chiming sequence begins.

This clutch, for which a new patent was filed, remains a rocker carrying two pinions. One pinion is permanently linked to the ratchet staff, while the other can be engaged or disengaged from the barrel through the pivoting action of the rocker. When the rocker pivots into its uncoupled position, the striking train is no longer driven, allowing the racks to fall and sample their cams. In the latest evolution, however, the locking function is no longer integrated into the clutch. Previously, the rocker itself carried a beak that pivoted into the stop star to arrest the train when disengaged, so the clutch lever physically bore the reaction force of the barrel torque. Now, that duty has been reassigned to a dedicated blocking lever which independently engages the same stop star mounted on a wheel of the striking train near the regulator. Its operation is governed entirely by the motion of the racks.

As the quarter rack falls, a pin on its arm pushes the blocking lever aside, disengaging its beak from the stop star and freeing the train. During striking, an isolation lever holds the blocking lever clear to prevent accidental re-engagement, and at the end of the sequence, a second pin on the hour rack resets the system by releasing the isolation lever, allowing the blocker to swing back and lock the train once more. By separating the two functions, the clutch itself is mechanically isolated from barrel torque throughout this process, and the release system no longer has to overcome that load. As a result, when re-engaged, the clutch couples to a completely stationary train without resistance, allowing the mechanism to accelerate smoothly from rest and deliver power to the striking sequence with greater efficiency.

The motion of the clutch rocker is still commanded by the quarter rack feeler, which acts on a primary clutch control lever. This lever deflects a secondary clutch lever and its fork that retains the rocker’s pivot pin. In this way, the quarter snail continues to govern the precise moment when the clutch is released and the racks are free to drop.

The rocker is held in its engaged position by a manual release system – the subject of a second patent – comprising a main lever, a bistable lever, a drive lever with a retractable beak, a release lever and a safety lever. When the push-piece is pressed, the bistable lever snaps through its tipping point and carries the drive lever forward, pushing the retractable beak against the release lever. This action frees the clutch rocker, allowing it to pivot into its disengaged state so the racks can fall and read their cams. The release lever immediately springs back once the beak passes, so even if the push-piece is held down, the clutch cannot re-engage prematurely or cause a restart. The safety lever blocks any new trigger while the strike is sounding. Once sampling is complete, the quarter rack raises the clutch lever back into engagement, and the strike proceeds without risk of a double trigger.

A further safeguard, the third patent, prevents the mechanism from operating when there is insufficient energy in the striking barrel. The power reserve display wheel carries a protrusion that, when the reserve falls below a threshold, pivots a secondary control lever. This lever in turn rotates a deflecting piece into the path of the retractable beak on the drive lever. Blocked before it can contact the release lever, the beak folds back harmlessly under spring tension. The release lever therefore remains in its rest position, the clutch stays engaged, and the strike cannot be triggered.

When the winding stem is pulled into its time-setting position, the setting lever actuates another control lever linked to the same deflecting piece, which again moves into the path of the retractable beak. The beak folds back under spring tension, so the release lever remains at rest, the clutch stays coupled, and the racks and feelers are prevented from dropping while the cams are being rotated, eliminating any risk of interference or damage during setting.

What most fundamentally distinguishes a grande sonnerie from a minute repeater is a mechanism that governs when the watch will strike and what it will strike. This is the function of the mode selection device, the subject of the fourth patent. It allows the watch to alternate between grande sonnerie, petite sonnerie and silent modes by selectively blocking or freeing the components that trigger the chime. At its heart is a column wheel, which functions as the central switch. Each slide advances the column wheel by one step, cycling the mechanism through its three modes.

The column wheel coordinates a set of isolating levers, each with a specific role. The first isolating lever controls the automatic release rocker — the component that drops every quarter hour to initiate a striking sequence. Depending on the position of the column wheel, the isolating lever either allows the automatic release rocker to move freely or holds it in a raised position where it cannot engage with the quarter star driven by the cannon pinion.

A second isolating lever manages the petite sonnerie lever, which suppresses the hour strike except at the full hours. A third isolating lever serves a safety function by holding the pawl that advances the grande sonnerie star away from its teeth during mode changes, preventing accidental triggering.

In grande sonnerie mode, the first lever leaves the automatic release rocker free to operate. Every quarter hour, the rocker is lifted by the quarter star with four teeth fixed to the cannon pinion and then released by its return spring. As it drops, it advances the 12-tooth grande sonnerie star integral with a wheel in the release system. This motion briefly raises the drive lever, causing the retractable beak to actuate the release lever, which frees the clutch. Once uncoupled, the racks fall to read their snail cams and trigger the strike.

In petite sonnerie mode, the mechanism must suppress the hour strike except at the full hours. A three-tooth star fixed to the minute wheel rotates once every three hours. Each time one of its teeth passes, it lifts an hour-suppression lever out of the path of the hour feeler, allowing the hour rack to fall and the hours to be struck. For the rest of the time, the suppression lever remains in its rest position, blocking the hour feeler except on the full hours when the three-tooth star lifts it.

In silent mode, the column wheel pivots the first isolating lever to hold the automatic release rocker in a raised position, out of reach of the quarter star. With the rocker immobilized, the drive lever is never actuated, and the clutch remains engaged. The racks cannot fall to read their cams, the sampling phase never begins, and no energy is drawn from the strike barrel.

An additional safeguard is built into the mechanism. When switching from silent mode back into an active striking mode, the isolating lever and the automatic release rocker briefly brace against one another in an intermediate position. This controlled pause ensures that the rocker does not crash into the quarter star and risk slipping the cannon pinion. Only when the next quarter arrives does the star itself nudge the rocker past this point, allowing the mechanism to resume normal operation. Through this coordinated system, the mode selection device determines precisely when and how the watch will chime, while preventing damage and unintended operation.

Acoustic System

A minute repeater or grande sonnerie typically has two gongs of different pitches which are screwed to the mainplate by a metal foot, with each encircling the movement in opposite directions. The pivots of the hammers are located right next to the foot on the bridge side of the movement. But in Chopard’s chiming watches, the construction is inverted; the hammers and gongs are located on the dial side, which allows the striking to be observed on the dial while the sound generated by gongs can travel forward towards the wearer.

Normally, both the hammers and gongs are made of hardened steel. The hour hammer strikes a low-pitched gong, while the minute hammer strikes a high-pitched gong. Each hammer is connected to a pallet on the underside by a pin, which is impulsed by a return spring to allow the hammer to strike the gong.

Beyond the complexity of translating the motion of the hands into strikes, a chiming watch ultimately lives or dies by how it sounds. Each must contend with the challenge of transmitting vibrations from thin steel rods into open air, and every junction in that path represents a point of loss. As the gongs are part of the movement plate, sound has to travel upwards through the movement plate, dial and crystal, as well as laterally through the caseband when the watch is on the wrist. Each interface introduces compromise, dependent on tolerances, surface finish and even the torque applied to screws, potentially dampening resonance before the note can even leave the watch.

In 2016, Chopard’s Full Strike proposed something entirely new. The gong, heel and crystal are machined from a single block of sapphire crystal, notably without any bonding agents. Scientifically attested by the Haute École du Paysage, d’Ingénierie et d’Architecture in Geneva (HEPIA), the breakthrough eliminated interfaces altogether, uniting the source of sound and its amplifier. The Grand Strike carries this solution forward.

Sapphire, with its high speed of sound, offers mechanical and acoustic continuity, enabling the crystal itself to serve as a resonator. To achieve this, the sapphire blank is shaped by diamond-tool CNC and refined by laser where geometry demands. This allows the thin, curved profiles of the gongs to be precisely defined without fracturing the brittle material. The surfaces are then optically polished to restore structural uniformity and eliminate micro-cracks that could dampen vibration. The result is a true monolithic acoustic architecture, where the speed of sound and mechanical impedance remain constant across the entire structure. This continuity allows the chime to propagate with exceptional clarity, free from the distortion or energy loss. Additionally, where steel can bend and fatigue, the monocrystalline lattice of sapphire does not deform under repeated excitation. The result is what Chopard calls the “Sound of Eternity,” and in both the Full Strike and the Grand Strike, it has been tuned to a C♯–F dyad, a sonorous interval chosen for its stability and unity.

It’s an unconventional choice in horology because most minute repeaters and sonneries are tuned to harmonious intervals like a minor or major third, which sound pleasing and consonant. The tritone, by contrast, has a slightly tense and ethereal quality which suits the clarity and power of sapphire gongs.

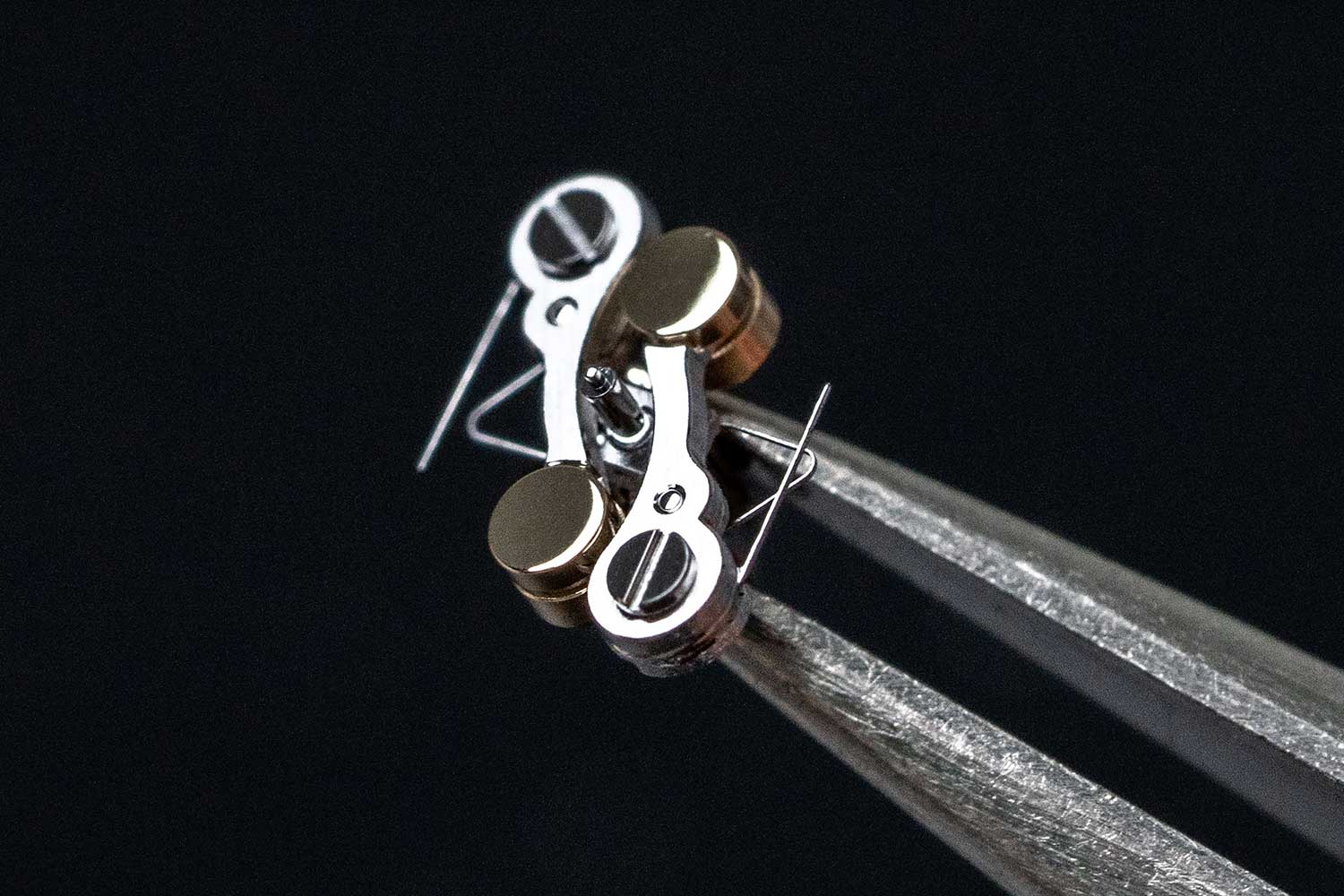

The hammers, on the other hand, are made of hardened steel that has been black-polished. Because sapphire is brittle, they have an optimized geometry that alters their moment of inertia to minimize impact energy on the sapphire gongs and helps prevent damage in the event of accidental shocks. This is the subject of the fifth patent. The hammer has a stepped two-level construction. The heel and the tip of the hammer are on one plane, effectively forming the upper layer, while the main body is a thin section connecting them, forming a lower layer.

By recessing the main body below the plane of the heel and striking tip, the hammer achieves a substantial reduction in mass and shifts its center of gravity closer to the pivot. This reduction in rotational inertia means that even if the hammer is accidentally released due to an impact or sudden acceleration, the energy transmitted to the gong is dramatically reduced. Yet when the hammer is driven intentionally by the striking spring, the lighter construction allows the striking tip to accelerate more quickly, producing equal or greater sound intensity and preserving the tonal clarity and harmonic complexity of the chime.

In the end, a grande sonnerie, even when perfectly executed, is an instrument balanced on the edge of failure. To ensure robustness in use, the Grand Strike prototype endured a quality control regime at the Chopard manufacture that subjects it to 62,400 activations of the sonnerie — half in grande and half in petite mode — an accelerated test that compresses five years of wear into just two months. During this same period, the minute repeater is operated 3,000 times through the pusher to verify the endurance of every spring, rack and lever.

Further Considerations for Chronometry

The L.U.C Grand Strike also incorporates a one-minute tourbillon at 6 o’clock. The cage features the brand’s distinctive spiral design and is supported by a steel bridge. The tourbillon is classical in construction, made up of an upper and lower plate joined by three pillars. A seconds hand is mounted on its upper pivot, and there is a hacking function, which stops the cage via levers when the crown is pulled out during time-setting.

The balance runs at a frequency of 4Hz, which is higher than the standard frequency in most tourbillon movements. All things being equal, a higher frequency balance maintains more stable timekeeping in a wristwatch as it is less susceptible to shocks caused by wrist motions. The balance is free-sprung and has a smooth, uninterrupted rim designed to minimize air friction during oscillation. It has U-shaped movable weights that are friction-fit and recessed entirely within the rim. Its hairspring uses a Phillips outer terminal curve, named for the French mathematician-engineer Edouard Phillips, who in the 1860s derived a theoretical geometry for the overcoil that makes the spring “breathe” more concentrically. His work put Breguet’s earlier overcoil on a rigorous mathematical footing and, when correctly executed, improved isochronism across amplitudes.

One subtle detail is that tourbillon Swiss lever escapement adopts an uncommon approach to the geometry of the pallet fork. Instead of a traditionally assembled lever with separate horns and guard pin, these elements are formed together as a single, monolithic component. The fork is structured on three distinct planes: the body and guard pin share the same upper surface, while the horns are set on a lower, inclined plane. This clever arrangement allows the impulse pin of the balance to be positioned very close to the safety roller without risk of interference. As a result, the balance requires a smaller lift angle, improving efficiency and reducing the escapement’s sensitivity to disturbance.

To further refine its operation and manufacturability, the horns are separated from the guard pin by full-depth recesses. These openings give the structure flexibility under shock while also facilitating precise machining of the horn surfaces. The guard pin still performs its traditional safety function, preventing the lever from overbanking during sudden impacts, but because it is integrated and dimensionally compact, it introduces no unwanted height or frictional complexity.

The movement is COSC-certified which is unusual for a chiming watch, and Chopard may be the only manufacture routinely submitting such pieces for chronometer testing. Certification was carried out with the watch in petite sonnerie, which is widely regarded among watchmakers as the most demanding mode. Because the mechanism that suppresses the hour strikes at each quarter consumes more energy than simply letting the chime run its full course, it was, in their view, essential to test the movement under those conditions.

Parts as Art

The quality of finishing is commensurate with the ambitions of the watch. The baseplate, as are the bridges, is made of German silver, adorned with perlage. It provides a warm and luminous backdrop against which the steel and brass of the strike works stand in wonderful contrast. Around jewel sinks and screw heads the countersinks are mirror-finished, while the surfaces of the bridges themselves are dressed with crisp, even striping that stops cleanly at the bevels. The bridges are rounded by hand and carries definition at the points and inflections.

The finishing achieves functional clarity and a clear sense of hierarchy. The racks, feelers and clutch parts are straight or circular-grained, allowing the black-polished hammers, tourbillon bridge and governor housing to stand out. Despite its sheer complexity, each part can be read clearly. It balances visual harmony with mechanical sense and bears the Poinçon de Genève. Put simply, the mechanism is clear because the finishing makes it readable and the sound is clear because the finishing makes it efficient.

Outside, the white gold case middle is satin-brushed that sets off the polished bezel and back. The lugs are individually finished and soldered to the case middle.

Above and Beyond

In the end, this is a watch that speaks for itself. A grande sonnerie, even in its most conventional form, represents the terminus of watchmaking effort and skill. It is the summit reached by only the few who can bring order to hundreds of interdependent parts, each one capable of throwing the mechanism out of order by a fraction of a millimeter. Yet, the L.U.C Grand Strike goes beyond this. It reimagines the architecture of the chiming watch from its foundations upward, addressing problems that most makers have long accepted as givens.

This is what makes the Grand Strike such an extraordinary accomplishment. It doesn’t rest on the mastery of skills that are already near impossible to acquire and master but pushes past them. Every layer has been reconsidered from the acoustics of transmission to the strike works to the train, the coupling and the all-important safety systems. It proves that with great patience, ingenuity and appetite for hard problems, progress remains possible even in the most complex of complications, where part counts are daunting and the underlying logic borders on the intractable. As an anniversary marker, the Grand Strike offers proof of accumulated judgment, of mastery over the hardest problems and of a workshop now capable of work at this level as a matter of course.

This article was originally written as the cover story for Revolution Arabia.

Tech Specs: Chopard L.U.C Grand Strike

Movement: Manual winding L.U.C Caliber 08.03-L; 70-hour power reserve (timekeeping); 12-hour power reserve (sonnerie); 4Hz or 28,800vph

Functions: Hours and minutes; tourbillon with small seconds; grande and petite sonnerie, minute repeater

Case: 43mm × 15.58mm; 18K ethical white gold

Dial: Open-worked; 18K ethical white gold hour markers

Strap: Interchangeable gray alligator leather or gray calfskin; 18K ethical white gold folding clasp

Price: CHF 780,000

Chopard