The Legend of Franck Muller Part 2: Frank Muller and the Tourbillon

News

The Legend of Franck Muller Part 2: Frank Muller and the Tourbillon

What is particularly extraordinary about Franck Muller is that he was the first great watchmaker to ply his craft after the onset of the electronic era — a time when mechanical instruments had been superseded by electronic ones. Throughout the ’70s, Swiss watchmaking was devastated by easily produced, inexpensive, battery-driven quartz watches which offered up a level of precision which had heretofore never been achieved by mechanical watches. It was amid this period of massive retrenchment throughout the industry, and uncertainty in the very sustainability of horological culture, that Muller would enter L’Ecole d’Horlogerie de Genève (the Geneva School of Watchmaking).

Says Muller, “If it had not been for Nathan Schmulowitz, one of the big watch experts at Antiquorum — an auction house dedicated to preserving the high arts of watchmaking — I might have never become a watchmaker. I was 15 years old and had decided to make my career in mosaic work because I was good with my hands. I had come to his attention because I loved to work on mechanical objects. Basically, I would disassemble anything and try to put it back together. Amused by me, Schmulowitz suggested that I try my hand at watchmaking. I asked him, ‘But what if I don’t do well?’ You have to remember that at that time, the watch industry was in peril, the Swiss had retrenched 80,000 people, factories were closing each day and major houses were selling movements by the kilo. He jokingly said, ‘Well, don’t worry if you fail — by the time you graduate, there probably wouldn’t be any jobs anyway!’ Of course, he was joking, because he was still deeply passionate about horology. What he wanted to see was whether I would become infected with the same passion.” What is clear is that even at this early age, Schmulowitz saw raw talent in Muller. Says Franck, “Schmulowitz believed that with so many people turning their backs on watchmaking, there was a real threat that there would be no one to take care of the vast horological riches of the past.”

But such was Franck’s capacity to absorb information that he soon proved himself to be a prodigy. He explains, “I began watchmaking school and finished in the accelerated program in three years. I’d just turned 16 when I entered. I took all of the top Swiss first prizes for student watchmakers during this period. However, I should point out that I was not always a good student. In fact, previous to becoming a watchmaker, I was a terrible student who was consistently at the bottom of my class. It was only when I became a watchmaker that I discovered what I was talented at, what God had put me on the earth to do. And from the day I stepped into watchmaking school, I never scored anything less than a perfect mark.”

But delving deeper, Franck reveals a more important emotionally resonant motivation for his perfectionism. He states, “When I was young, in the classroom, I always tried to stay focused on the book in front of me, but my eyes were always drawn to the birds outside. I have a brother and he was always the top student in our class and I was always the worst. At the end of each semester, my father would look at our grades and I could see the disappointment in his eyes. This lasted all the way until one day, I came to him and explained that I wanted to enter watchmaking school. He asked me, ‘Are you sure you will finish?’ I said to him, ‘Father, I will finish, and when I graduate, it will be as the top student.’ When I did, I could see that finally, he was proud. Unfortunately, he died not long after, and so, he never really saw what I became and what I ultimately achieved in watchmaking.”

Passion was what drove Franck, and the more he plunged into horology, the more he began to understand its cultural significance. “It would have been impossible to do well in watchmaking school if I wasn’t passionate, if watches had not resonated for me on an emotional level. It was as if using my hands and mind, I could understand a universal language that God had bestowed on man. It was a language that transcended all cultures.

Time was a language that was understood in every civilized corner of earth and the fact that we could create these extraordinary machines was, to me, something extraordinary… I have often said that if you break a watch down to its basic components — wheels, springs… just pieces of metal — it is a miracle that it works at all. That it must work constantly, that it is the sole device ever created by man that is asked to function flawlessly, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year… is something truly incredible.”

As he neared completion of his studies, the seeds of a dream began to germinate. But he kept his desire hidden from even his closest friends for several years. He explains, “I had the idea to create a brand almost immediately after I left watchmaking school. I could already see clearly in my mind what I wanted to do, which was to elevate this language of watchmaking to an even higher level of expression. I wanted to create an evolution that would unveil hidden truths about the way human beings express time. I wanted to connect the values of traditional Swiss horology to the contemporary world. But of course, I had no money to start my own brand. Fortunately, the beginning of my brand came about thanks to another Swiss brand called Rolex.”

“My father would look at our grades and I could see the disappointment in his eyes… Until one day, I came to him and explained that I wanted to enter watchmaking school. I said to him, ‘Father, I will finish, and when I graduate, it will be as the top student.‘“ — Franck Muller

Franck explains, “One of the prizes I won for being the top student in Switzerland was a watch from Rolex. I have gone on record stating that from the perspective of value and function, Rolexes are probably the best watches in the world. But when I wore this watch, I felt it was too simple. So, I decided to transform it into a perpetual calendar with retrograde indications. The idea was to do this without making the movement any bigger. So, I removed the Datejust mechanism and, in the same space, created this retrograde perpetual calendar. You must bear in mind that I did this in 1978, and at the time, there was no such thing as a retrograde perpetual calendar wristwatch.”

Franck continues, “The watch they had given me was signed Rolex and had my name on it because I had won the top prize. So when I created a new dial for the watch, I signed it ‘Rolex and Franck Muller’ out of respect for the brand. Then I took the watch to Rolex and I showed it to them because it was my idea to produce it for the brand. I remember that I met with an enormous office of Rolex engineers. They tested it for several days, but decided finally not to produce it. They explained that the philosophy of Rolex was to produce the simplest but most reliable watch possible. They said reliability and simplicity was their religion.”

But as it happened, collectors had already caught wind of the unique timepiece which the young upstart watchmaker had created. Franck immediately capitalized on this, “I sold this watch to pay for all my watchmaking instruments. At that time, it was the only way for me to raise the capital. Incredibly, this watch ended up setting a record for a steel watch two years after I sold it. I sold the watch for 10,000 Swiss francs to a gentleman named Francis Meyer. His father was an extraordinary pocket-watch collector and they are a very well-known family in horology. He sold it to an Italian distributor of watches, who then sold it to a collector in Monaco for 400,000 Swiss francs. And so, I had the record for the most expensive steel wristwatch ever sold. This record stood for five years. Years later, I tracked down the current owner of the watch, a Japanese collector residing in New York. I made him a generous offer to buy the timepiece back, but he turned me down.”

Before Franck Muller embarked on his solo career, he realized that he still needed to plunge into the world of practical watchmaking as well as that of watch and clock restoration. He found the ideal teacher in Svend Anderson, who was, in many ways, a throwback who preferred to work using the time-honored methods of high watchmaking. Franck benefited greatly from this. He explains, “The beginning of my story in watchmaking coincided precisely with the end of traditional high watchmaking. Previous to the modern age, watches were made almost entirely by hand. The designs for watches began entirely within the minds of watchmakers. There were no computer programs to perform simulated testing on complicated mechanisms. So with each watch, you ran an enormous risk, because in the end, you never knew if it would work or not.”

This was the way high watchmaking worked for several hundred years. Then came the Quartz Crisis in the ’70s. In the ’80s, as the watch industry rebuilt itself, it did so using a fantastically powerful tool called the computer. The computer could assist machines to create complex parts, and it enabled technicians and micro-engineers to enter horology using their ability in three-dimensional rendering. It also allowed rapid prototyping. In short, the computer changed the watch industry forever. But in so doing, it also took something from watchmaking: it took a bit of that ineffable human spirit and diminished in some way the measure of soul that went into each watch; it unraveled the time-honored equation of the watchmaker pitting his intellect, creativity, manual dexterity and internal fortitude against the laws of physics. It was no longer a matter of man literally trying to bend time to his will — it became an age of automation. Franck Muller was the rare watchmaker with equal abilities in both traditional and modern watchmaking. Though, as he describes it, the path to knowledge in traditional watchmaking was akin to the cruel tutelage of ancient kung fu masters.

Franck Muller understood that if the emotional impact of the tourbillon was the main criterion, then the mechanism had to be placed where it was most readily visible

Franck explains, “Because everything was made by hand, the world of watchmaking was an immense world of secrets. Every great watchmaker had his secrets, his method to make time obey him, to activate the heartbeat inside the watch. Watchmakers were paid for the movements they made. A big brand would approach us and say, ‘Make me 10 movements with these specifications,’ but they wouldn’t tell you how to make it, because they didn’t know. So, each watchmaker was responsible for delivering the best movements he could, but in a way that was most efficient for him. As a result, watchmakers developed their own techniques. They made their own tools to solve certain problems, and when they were done with their job, they would lock all the tools away inside a drawer or box and keep all their techniques buried in the recesses of their own minds.”

When asked how a student would learn the secrets of his master, Franck laughs and replies, “There was one way to gain the secrets of these old masters, but it was a hard path to follow. You would have to become their apprentice and labor for them in any capacity they wished. Then if they trusted you, they would allow you to watch them. But they would never explain anything, so you had to unravel the secrets as they worked. You had to memorize each move and comprehend the underlying logic of their technique without ever uttering a word or receiving one iota of instruction. This was the ancient way in which secrets were passed from master to pupil for centuries, and it guaranteed that these secrets would only be passed to watchmakers skilled enough to receive them. In many ways, it was a form of natural selection.”

Franck soon proved himself an extraordinarily fast learner: “My secret was that I could repeat what I saw quite easily from memory. After Svend Anderson demonstrated something, I would immediately sit down at my bench and repeat it. Anderson was very strict. He would examine what I did with a 3x loupe. If there was even the smallest imperfection, he would simply throw the part away. I always worked without a loupe — I’ve never worn one as I have a very good eye. But when it came time for Anderson to check the part that I had made, I would always pre-examine it with a 10x loupe. My rationale was that if I cannot find any flaw at a magnification of 10, he won’t find any at a magnification of three.”

Throughout his days with Svend Anderson, Muller labored incessantly, soaking up information and plunging into the past to see how old masters solved the age-old riddles of measuring time. It was during his immersion in the restoration of some of history’s most extraordinary timepieces that a vision for his first wristwatch coalesced in his mind. And when he finally did launch his brand, Franck would reach into horology’s past and transport one of its most iconic technical innovations into his first wristwatches.

Says Franck, “I was the first to put a tourbillon inside of a wristwatch. The idea came to me during the time I spent restoring antique pocket watches. This was a fantastic period. I was restoring some of the most famous watches and clocks ever made for Antiquorum, and later, for the famous museums as well. [It is well known that Muller and Svend Anderson restored the watches in the Patek Philippe Museum.] Watches would arrive and they would be missing key components, so we had to remake these but at the same time find historical documentation for the missing pieces, as well as interpret the horological language of the master who had fabricated them. I noticed around this time that the watches most avidly collected were the tourbillons.”

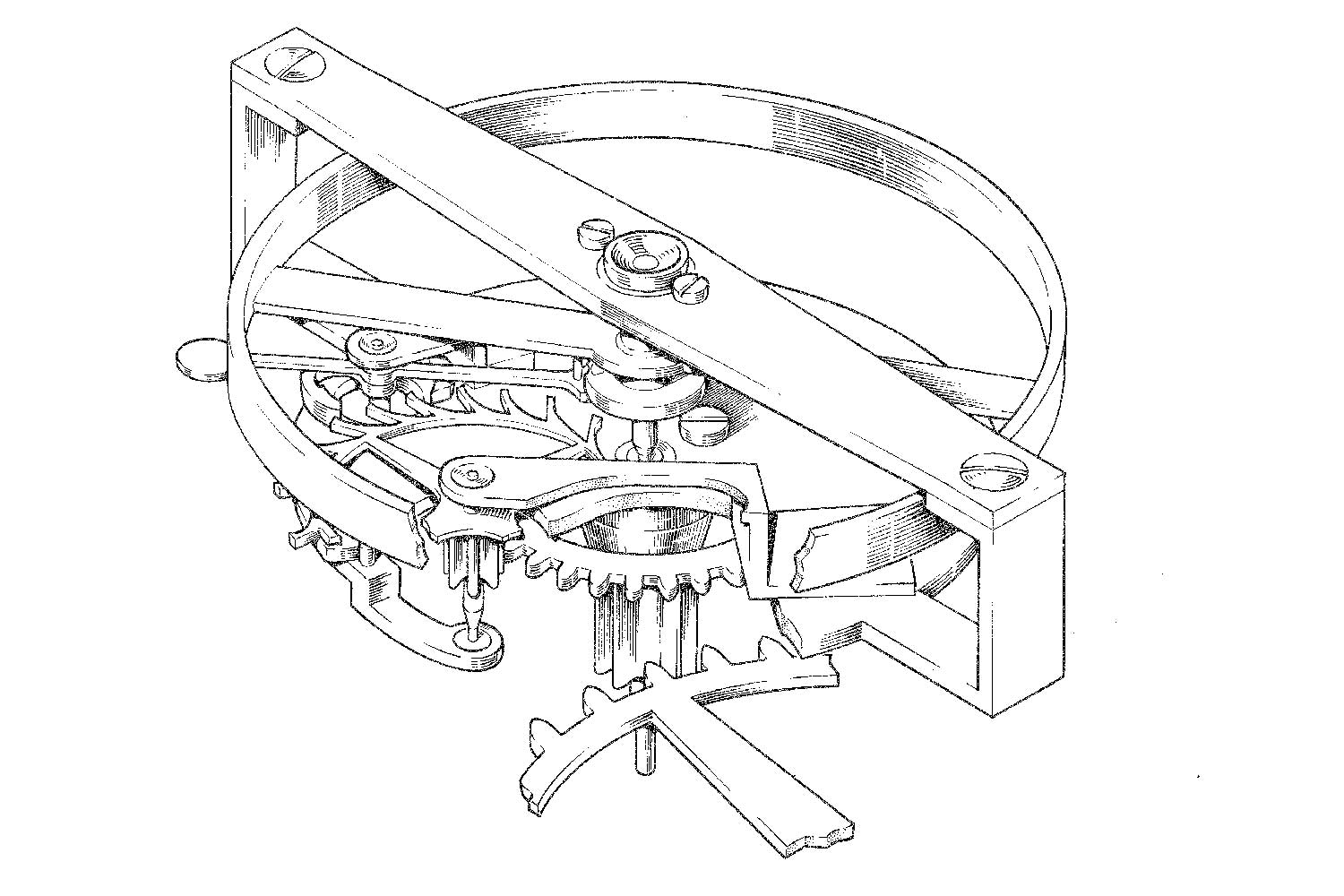

Franck Muller realized that the pocket watches with the most commercial potential were those featuring Breguet’s famous tourbillon regulator (shown here in the Breguet No. 1188). This gave him the inspiration to transport the tourbillon to the wristwatch with one major change — the tourbillon would be featured dial-side

Muller was quick to understand the attraction of the tourbillon. Patented in 1801, the device placed all the regulating components of the watch — essentially the parts that comprised its heart: the hairspring, balance and escapement — inside a cage that rotated on its own axis. This cage averaged out the positional errors (such as those caused by the non-concentric “breathing” of the hairspring) due to gravity, which are the most exaggerated when a watch is in the vertical positions. But Franck began to look beyond the simple pragmatic benefits of the tourbillon.

He explains, “When the tourbillon was first created, it was invented out of the need for precision, because of the negative impact of gravity on watches in the vertical position. But today, the rationale for a tourbillon is very different. If you want a truly precise watch, then you’ll get a quartz watch or you can use your mobile phone. But precision is no longer the goal. Today, these watches are more like works of art which demonstrate what is possible through human craftsmanship, and engage the user on the emotional level.”

But Franck also understood that if the emotional impact of the tourbillon was the main criterion, then the mechanism had to be placed where it was most readily visible. He explains, “When I made my wristwatch tourbillon, I decided to do one thing very differently than what you would find in the pocket watches. I decided to put the tourbillon on the front of the dial, because, after all, this was what the customer was paying for. This was the technical marvel, so why not make it the star? This way, someone who bought my watch could immediately show his friends that his watch contained a tourbillon.”

Look at any Franck Muller tourbillon wristwatch today and you’d be magnetically drawn into its magnificent microcosm: the constantly rotating cage and oscillating balance wheel that are reinforcements of the living persona of the mechanical watch. Says Franck, “We were living in a new era, a time when people were enjoying life. They were living life to the fullest and they wanted new symbols of success, and the tourbillon was it. As such, it was introduced into the lexicon of mainstream luxury.”

Look at any Franck Muller tourbillon today and you’d be magnetically drawn into its magnificent microcosm: The constantly rotating cage and oscillating balance wheel that are reinforcements of the living persona of the mechanical watch.

The dream of a brand

Muller’s announcement of his brand came soon after he and several other watchmakers decided to revive a famous Geneva watchmaking guild. He explains, “At that time, the three independent watchmakers who were working in Geneva were me, Svend Anderson and Roger Dubuis. The three of us decided to get together and recreate the famous guild known as the Cabinotiers de Genève, which was a group that comprised various artisans needed to make a complete watch: enamelers, casemakers, dialmakers, engravers and watchmakers. Michel Parmigiani and Philippe Dufour were the two other famous watchmakers at the time; however, as they lived in Fleurier and Le Sentier respectively, they were not eligible for membership. We did, of course, grant them honorary status because of their extraordinary abilities.”

But amusingly, Muller’s declaration that he would start his own brand was met with collective puzzlement: “One day, I said to the committee, ‘I am going to stop working on pocket watches.’ They asked, ‘What are you going to make then?’ At that time, I saw that there were two groups of watch collectors: the very traditional collectors of high complications who were primarily interested in complicated pocket watches, and a new contemporary audience that was increasingly interested in wristwatches. However, this was before the era of complicated wristwatches. So I told them, ‘I would like to take the traditional Swiss high complications and bring them into the wristwatch world. I have been analyzing the market and the pocket watch that brings the highest premium is the tourbillon. So, I will create a wristwatch tourbillon.’ They, of course, replied, ‘You’re crazy. Who are you to make a watch? You are not a brand, who will buy your watch?’ You see, at that time, watchmakers were not stars — they generally worked behind the scenes. They labored at the behest of big-name brands, as this had traditionally been the relationship for centuries. My response was naïve, but also, I like to think, realistic. I said, ‘Before Patek decided to start his company, he was just an individual.’ My point was that everyone has to begin somewhere!”

Franck knew that without the communication budget of a major brand, the watch he created had to generate enormous attention. He began rethinking his ideas for it, “I was not satisfied with a simple tourbillon. I wanted the watch to have a jump-hour indication — not an analog indication, but one that used hands to remain classic-looking because at that time, the analog indication was too reminiscent of quartz. The idea was to have the maximum dial-side animation possible so the drama of a jump-hour hand would elevate the kinetic energy of the watch significantly. What was nice about the watch was that you had the contrast of the tourbillon cage rotating once ever 60 seconds, and at the beginning of each hour, the hands would jump with this explosion of energy. The tension between these two movements was very exciting. Also, I knew that in order to make a name for myself, I had to create something that the world had never seen before, something that was daring yet which even the most refined collector would recognize as being horologically legitimate. In 1984, I completed this watch and presented it to the public. I sold it right away. The following year, I created a regulator-dial version of the tourbillon.”

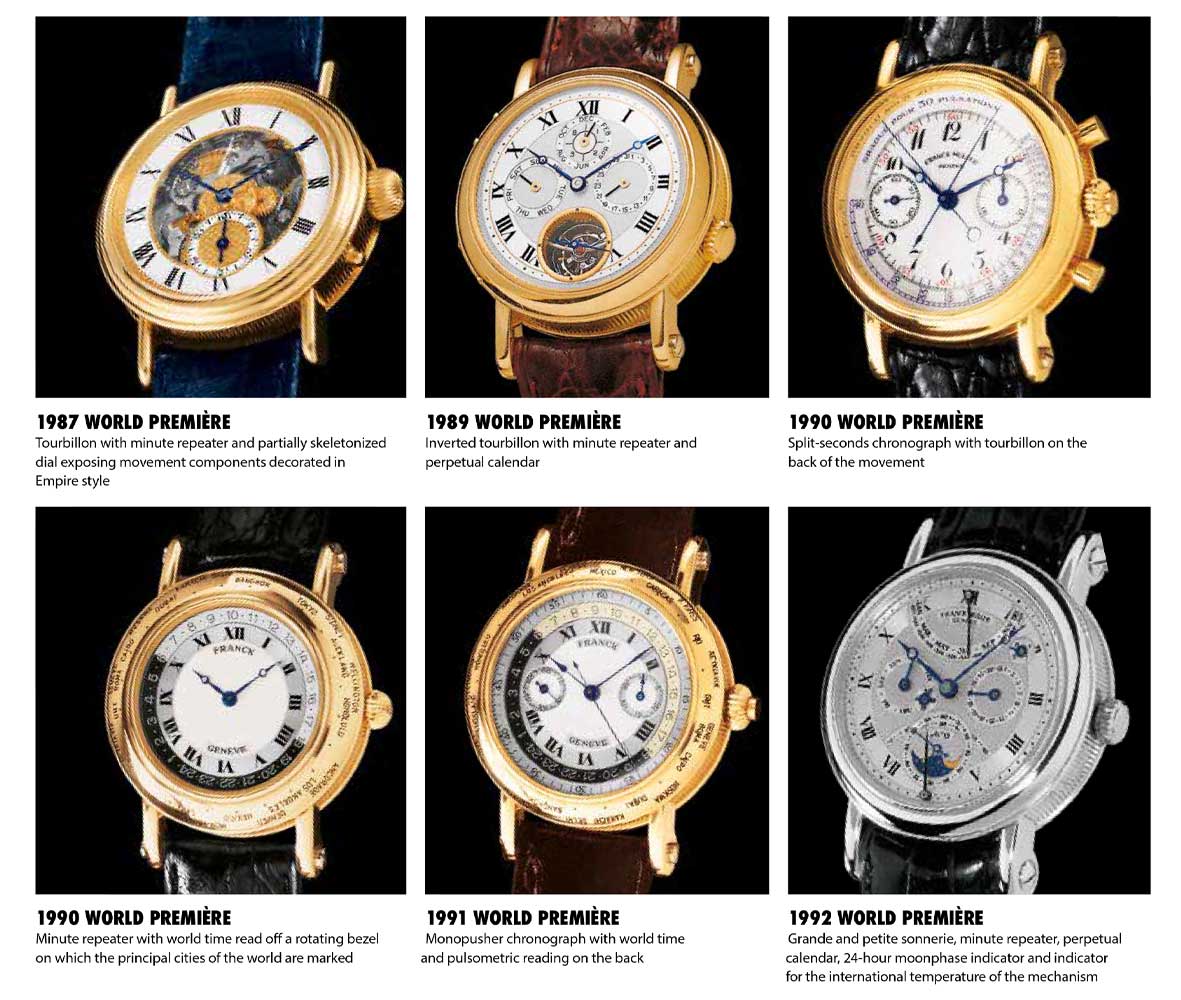

At the same time, Muller and his friends at the guild were bestowed a large honor which helped them gain even greater visibility. He recalls, “Our group was contracted to make a 10-piece production run of timepieces to celebrate the anniversary of the watch museum in Geneva. This really irritated some of the bigger brands — or rather, it made them nervous, I think, because they did not want the public to be aware that we were the people who were behind some of their most famous timepieces. This was not really our intention, but we wanted to be given a voice. As such, in 1985, we decided to create the AHCI [Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants], which today consists of 35 of the world’s greatest independent watchmakers, to celebrate and clearly put the spotlight on the work of independent watchmakers. Now that we were gaining momentum, I knew I had to submit something extraordinary. I was determined to create the world’s first-ever tourbillon minute-repeater wristwatch. At that time, the tourbillon for this watch was still at the back of the movement. Later in 1989, I wanted to make it even more complicated, so I created a tourbillon minute repeater with perpetual calendar, and with the tourbillon on the dial-side of the watch. This was very difficult because you had to move the minute repeater mechanism and also the perpetual calendar just so the tourbillon could turn on the front of the dial. It took years of work, and in the end, until the watch started beating, you had no idea whether it would work because no one had ever done it before!”

With each successive watch, Franck Muller’s fame grew. Soon, some of the world’s most famous watch collectors were tracking him down in his small Geneva atelier, but his work continued, unimpeded by the success: “After I created the tourbillon minute repeater, I went after an even more elusive goal, which was to create the world’s first tourbillon with split-seconds chronograph. Not many people realize that a chronograph is actually one of the most difficult mechanisms to create, and a split-seconds chronograph that enables the user to measure split times is even more crazy. I did not use an isolator mechanism for the split-seconds mechanism; instead, I used a big gold balance wheel with enormous inertia, so much so that the split function could be left on for up to three minutes without the balance’s amplitude being affected.”

Muller’s thirst forever-mounting complications was insatiable, and time after time, he dazzled watch enthusiasts. He recalls, “After this, I made a split-seconds chronograph tourbillon with perpetual calendar. The issue with this kind of watch is that, say, it is midnight at the end of the year — when the movement is causing all the perpetual calendar functions to instantly jump forward — and if you activate the split-seconds chronograph function, the balance wheel must continue to oscillate without a significant drop in amplitude. This was the challenge for this watch, because it is not enough to simply combine complications — you had to understand how they have a profound effect on one another. This is a watch that costs 350,000 Swiss francs, so of course, it must function perfectly. In addition, at that time, I was still working on my own, making every part of the watch by hand.”

The creation of a brand

From 1984, throughout the ’90s, and well into the new millennium, Franck Muller would dominate watchmaking, introducing new mind-blowing complicated world premieres, including the world’s most complicated wristwatch in 1992 which featured complications such as a grande and petite sonnerie, retrograde perpetual calendar, and even a thermometer. But there was one limitation to all of these watches, which was that Muller alone was responsible for each movement. He knew that if he wanted to reach a wider audience, he would have to evolve his vision.

Franck tells us, “I started to receive many watch enthusiasts, but because I was working on watches in the old way, making each piece by hand and by myself, I couldn’t satisfy many of them. At the time when I was doing this, I recognized that people were excited by complicated watches again, and there was a gap in the market for accessible complications. So, based on the Valjoux 7750 chronograph movement — one of the most reliable movements around, and more importantly, one of the few available chronographs at the time — I patented the first rattrapante [split-seconds chronograph movement] that could be industrially produced. I took out the calendar mechanism, and in its place, I put in the split-seconds mechanism, which had to occupy a very small space. This became the first series of watches I produced on an industrial level. Later, there would be 17 brands that would end up using this patent. I ended up licensing this mechanism to these brands, and today, there are still brands that use it. People kept asking me to make this movement for them, but I told them, ‘No, I have to focus on my own work.’ But the more I thought about it, the more I thought I would like to communicate my particular perception of high watchmaking to a wider audience.”

At this point, Franck met the individual who would allow him to realize his dream. He explains, “It was at this time that my associate Vartan Sirmakes arrived with the idea to transform my vision for watchmaking into an international brand with a profound global presence. He was, at that time, a casemaker fabricating some of the most complex cases in the industry, such as the Daniel Roth ellipse- shaped model. At first, he sent others, then finally, he came himself. I remember that he came to my garden in the month of August. He said, ‘Look, I make some of the most complicated cases in the world. Together, we can create a brand.’ I thought about it. At that time, I made movements, but I would buy the cases from a friend. Because my production was so small, it was only three or four cases per year. This was an excellent supplier who, at that time, also made cases for Patek Philippe and Blancpain. But because it was such a small production, I was a low priority. So I replied, ‘Why don’t you keep your case business and I will keep my grande complication business, but at the same time, we can create an association to produce watches in series that correspond to what I feel the world needs in terms of horology? Something with exquisite movements, something that reintroduces traditional Swiss high watchmaking, but with a fresh, contemporary perspective.’ You see, I was already thinking that for the Swiss industry to come back, we had to do it in a way that made our traditions relevant to an all-new generation.”

“Every Franck Muller watch is born out of pleasure and never as a commercial necessity. Every timepiece we’ve made has tried to bring something new and innovative to horology, to help in the evolution of its continuous story.” — Franck Muller

Says Franck of his vision for his brand, “I was always mindful to retain complete creative control over every timepiece. Every Franck Muller watch is born out of pleasure and never as a commercial necessity. Every timepiece we’ve made has tried to bring something new and innovative to horology, to help in the evolution of its continuous story. By 1992 we were showing our watches at the SIHH. We were incredibly successful, particularly in Italy. I had already developed a following there because in those days, the center of watch collecting was based in Italy. Everyone considered this market as the most sophisticated in the world — it was the first to produce beautiful watch magazines and it was the home to some of the world’s most important collectors. Perhaps it was the Latin flair of the nation combined with their deep roots in science and culture, but they were the first to completely embrace my vision of combining true authentic high watchmaking with a certain contemporary spirit. Many of the unique pieces I created ended up being worn by famous Italian industrialists. They did not want to show up at a board meeting and see someone else wearing the same watch on their wrist. From there, the brand began to take off. Some early adopters including Gianni Versace, and later, Elton John, which helped the brand become well known in the United States; others like Jackie Chan helped make Franck Muller a recognized brand internationally. However, I’ve always had one objective in mind, which is to ensure that our watches are emotionally impactful — that they delight their owners while representing the finest quality in the Swiss industry.”

One major boon to Franck’s obsession with quality has been Watchland’s extraordinary manufacturing depth. It is the only brand that manufactures 100 percent of its own cases and dials. Every movement is fabricated and assembled on premises in Genthod, and subjected to the strictest levels of quality control and internal testing; only in this way would they resonate as true Franck Muller timepieces.

“I’ve always had one objective in mind, which is to ensure that our watches are emotionally impactful — that they delight their owners while representing the finest quality in the Swiss industry” — Franck Muller

Franck Muller