Inside the H. Moser & Cie. Manufacture in Schaffhausen

Editorial

Inside the H. Moser & Cie. Manufacture in Schaffhausen

In little more than a decade, Moser has travelled a distance that most independent brands never manage at all, from near obscurity to a position of genuine commercial success and influence in contemporary watchmaking. Explaining why this has happened is not especially easy. Part of the difficulty is that the brand resists tidy categorisation. It is, at once, a serious manufacture with strong foundational competencies, and a brand that appears curiously indifferent to the codes by which high watchmaking normally signals its seriousness.

H. Moser & Cie. Endeavour Small Seconds Concept Pop. While hardstone dials are often enlisted as expressions of luxury, Moser’s Pop collection discards that sobriety almost entirely.

This tension is perhaps easier to understand when viewed against the brand’s longer arc. The company was founded in 1828 by Heinrich Moser, himself a trained watchmaker, and the son and grandson of watchmakers from Schaffhausen. Moser stood among the great 19th-century makers, with watches exported across Europe and, most significantly, to Imperial Russia. By the middle of the century, his enterprise employed several hundred workers in Switzerland, and approximately half a million watches were produced under his name during his lifetime.

Moser’s influence extended well beyond his own firm. He played a instrumental role in transforming Schaffhausen into a viable centre of industrial watchmaking, investing heavily in local infrastructure, notably hydropower from the Rhine, which enabled large-scale, factory-based production in a region previously dominated by artisanal cottage industry. These initiatives laid the groundwork for Schaffhausen’s emergence as one of Switzerland’s key industrial watchmaking hubs. The family home Heinrich Moser built overlooking the Rhine in Schloss Charlottenfels survives today as a museum and cultural site. It is less a monument to a brand than as a quiet record of a man whose ambitions helped shape not only his own enterprise, but the identity of Schaffhausen itself.

Following Moser’s death in 1874, the business was divided between its Swiss and Russian operations, the latter ultimately expropriated after the October Revolution. Over the following decades, the name persisted through restructurings, ownership changes and industry consolidation, increasingly as a historical asset rather than an active manufacture. By the time the quartz crisis arrived in the 1970s, its historical continuity had already been badly eroded. In 2002, it was formally revived but it struggled to find its relevance in a post-quartz, post-renaissance industry already crowded with revival attempts.

That reset came in 2012, when the Meylan family, through MELB Holding, acquired the Moser Group. The brand was financially fragile and little known beyond a narrow circle, yet it already possessed a full-fledged manufacture capable of proprietary movement development and production, and the support of its sister company Precision Engineering, a specialist in hairsprings and regulating organs. The turnaround led by CEO Edouard Meylan unfolded in phases, first restructuring and stabilisation, then industrial modernisation and re-engineering, and only later a recalibration of how the brand spoke to the world. Provocation, when it arrived, was not the point but the vector, designed to attract attention, then redirect it toward the watches themselves.

At the manufacture, it becomes clear that the irreverence rests on an unshowy but very real command of specialisations. The Moser manufacture is located in Neuhausen am Rheinfall, a short distance from the Rhine Falls, within a compact industrial complex whose neighbouring firms have no connection to watchmaking. The building is home to three companies – H. Moser & Cie, Hautlence and Precision Engineering. Our tour was led by Cédric Joos, who was appointed brand manager of Hautlence in 2025 after three years at Moser.

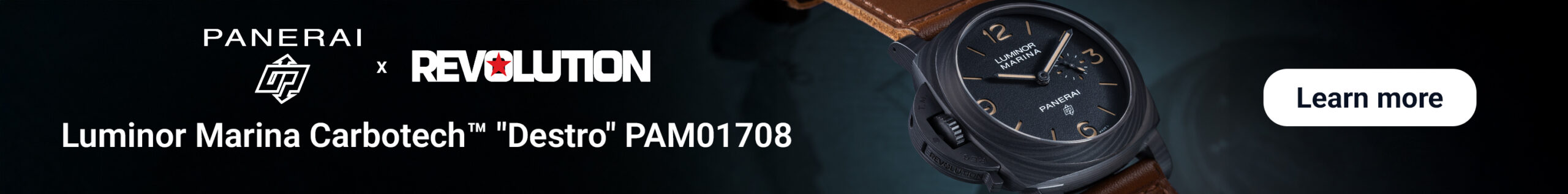

Construction room

The tour began in the construction room, where movements take shape in CAD and the geometry, tolerances, and spatial relationships of every component are determined. Parts are laid out in three dimensions, which allow clearances, engagement and kinematics to be resolved on screen, while ensuring that what is drawn can ultimately be manufactured, assembled and adjusted at the bench.

An engineer was present to walk us through the constraints and solutions behind the Calibre HMC 811 in the Pioneer Cylindrical Tourbillon Skeleton. He shared that once the movement is skeletonised, the rotor has to be skeletonised as well. That, however, immediately creates a problem, as a rotor needs mass to wind efficiently, and skeletonisation removes weight. Solving that contradiction was one of the key technical achievements of the movement.

Rather than using a peripheral rotor, the solution was to concentrate mass at the outer edges of the rotor, in areas largely hidden from view. It is a solution the customer never sees directly, but one that allows the winding system to retain sufficient inertia despite aggressive skeletonisation. To underline how structurally demanding this is, the engineer pointed out one of the rotor arms, machined to a thickness of just 0.33 mm. By comparison, a human hair measures roughly 0.1-0.2 mm in diameter.

The rotor itself is made from 18k gold, which provides inherent density, but that alone is not enough. Strength had to be engineered into the form. The arms were thinned as much as possible and skeletonised to the limit, with their final geometry validated through repeated simulations to ensure sufficient rigidity and resistance to deformation under load.

The rotor carries a wheel that turns on an eccentric wheel, which in turn transmits motion via a pair of pawls to the winding wheel. In one direction of rotation, one pawl draws the winding wheel back while the opposing pawl slips over the teeth. When the direction reverses, their roles switch, with the second pawl now advancing the winding wheel instead.

Conceptually, it is comparable to systems such as IWC’s Pellaton winding or Seiko’s Magic Lever. Like the Magic Lever, the clutch is executed as a single integrated component rather than multiple elements. The geometry of the system was developed entirely in-house, even if the underlying principle is well established.

The movement used as a starting point was the HMC Calibre 804, Moser’s long-running automatic tourbillon calibre. The objective was to create a skeletonised movement that could also accommodate a cylindrical hairspring. By reusing part of an existing architecture, certain wheels and systems could be retained, shortening the development phase considerably compared to designing an entirely new calibre from scratch. At the same time, the bridges and plates were developed specifically with skeletonistion in mind; it is not a finished movement that was later cut away.

The engineer noted that skeletonised movements pose a visual challenge as well. While they can appear striking under a loupe, they often reveal too much of the wrist, so the components were deliberately positioned to strike a balance, preserving the sense of openness without exposing too much skin on the wrist.

From there, the discussion moved to the cylindrical hairspring. Historically, cylindrical hairsprings were used in marine chronometers, where positional accuracy was critical for navigation. Unlike a flat spiral, which breathes asymmetrically due to being fixed on one side, a cylindrical hairspring expands concentrically. This reduces shifts in the centre of mass during oscillation and limits lateral forces acting on the escapement, improving rate stability.

In this movement, the cylindrical hairspring is combined with a tourbillon. The hairspring contributes concentric breathing and intrinsic rate stability, while the rotating cage averages positional errors in the vertical positions. The engineer emphasised that the tourbillon does not eliminate variation entirely, but it reduces positional discrepancies over time, resulting in a more stable average rate on the wrist.

He then moved on to another project to illustrate how development work is shared with Hautlence within the group. The movement shown was the Hautlence Caibre calibre A82 in the Sphere Series 3. It is based on Moser’s calibre HMC 200 but repositioned to accommodate a unique display module. The most complex element was the hour indicator, constructed from titanium blocks that rotate one and a half turns to indicate the next hour. The complication is sufficiently demanding that only Moser’s most experienced watchmakers, specifically those who also assemble the perpetual calendar, are entrusted with its assembly.

Asked about his background, the engineer explained that he trained first as a watchmaker before studying mechanical engineering. That dual perspective, he noted, is essential. A component can be drawn convincingly on screen, but once reduced to physical scale, machinability becomes critical. Radii, thicknesses and tolerances must allow for real-world manufacturing. A rotor arm measuring 0.33mm, for example, may look good in CAD, but it might not be machinable in practice.

Assembly considerations are addressed from the earliest stages. Certain components such as the sphere in the Sphere Series 3 require dedicated tooling and cannot be assembled without it. As a result, even assembly sequences are discussed with prototype and series-production watchmakers before parts are commissioned. Each step is reviewed in advance to determine whether it can be executed reliably, and in what order.

The engineer said that energy management is another constant constraint and for anyone who isn’t a watchmaker, it can be difficult to sense how much energy is required. Complications such as the spherical display require bursts of power, yet the movement must retain sufficient amplitude and power reserve. He explained that the movement is organised into three functional sections – the base movement, a transmission module that delivers energy to the complication, and the display module itself.

By reusing an existing base calibre and developing the complication as a modular system, development time and risk were significantly reduced. Previously, Moser’s watches sat in a range between CHF 80,000 and CHF 220,000, which is typical for a brand of this size, given annual production of around 200 pieces and often limited run of 28 watches. With this approach, the brand is now able to offer watches priced between CHF 30,000 and CHF 80,000. The Sphere Series 3 is priced at CHF 66,000, which he described as very attractive for such a unique time display. With that, the tour moved on to the hairspring production.

Hairspring Manufacturing

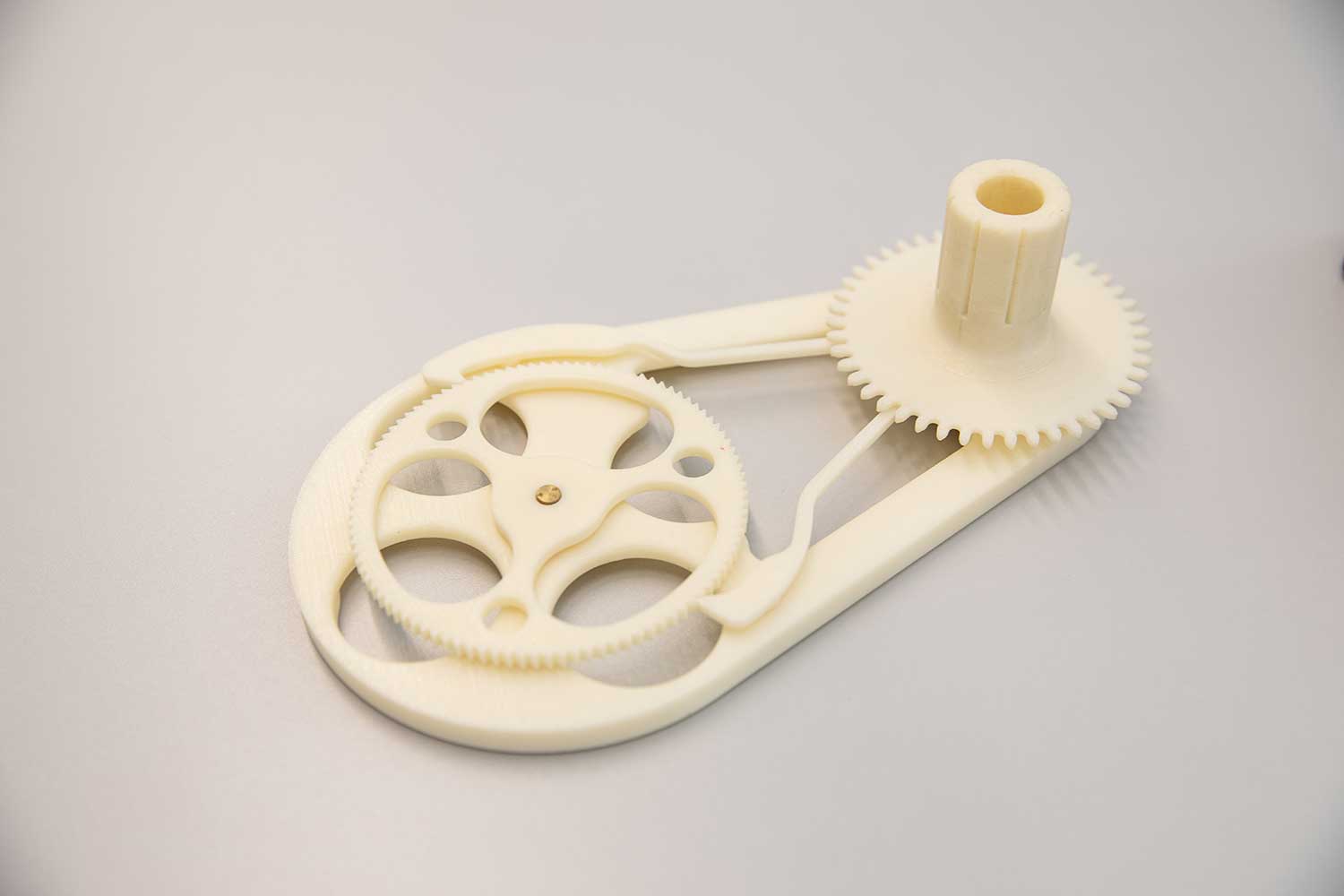

Precision Engineering is one of just 12 hairspring manufacturers in the industry. Unlike brands where hairspring production exists as a department, this is a standalone manufacture within the same building, thus its scale is correspondingly larger.

Cedric explained, “You can imagine the market at the time when we started. It is a niche within a niche. There were not many hairspring manufacturers, and the biggest one made its own rules. That meant that as a small watch manufacturer, you had to order quantities that made no sense.”

He continues, “So we specialised in supplying smaller brands. By focusing on that, we now produce about 200,000 hairsprings per year, compared to what we need internally, which is around 4,500, depending on whether a watch uses a single or double hairspring. This shows how small the niche really is.”

The process begins with a specialised alloy supplied in wire form, wound on large spools. Precision Engineering specifies the exact alloy mixture and send it to the supplier. Moser uses PE5000, an alloy composed of niobium and titanium. It is paramagnetic, highly shock resistant and possesses exceptional elastic resilience. Crucially, because PE5000 is a metallic niobium–titanium alloy rather than silicon, it allows the hairspring to be formed and adjusted in the traditional manner. This includes the formation of a Breguet overcoil, which can be shaped, trued and optimised by hand.

The wire starts off at roughly 0.6mm in diameter. The first step is diameter reduction by wire drawing. The wire is pulled through natural diamond drawing dies, which progressively reduce its diameter while increasing its length. This operation is repeated multiple times, with intermediate inspections, until the wire reaches its final diameter of 0.01mm.

He explains, “Because a lot of oil is used during this process, the wire must be cleaned afterward. It has to be as clean as possible, because at a later stage we heat it so that it keeps its shape.” At this stage, the cross-section of the wire remains round, while the profile of a hairspring is rectangular. Hence, the wire is then passed through a pair of rollers to flatten it.

“Hairsprings are produced in a separate room, because when we enter, we change the temperature.” Cedric explains, “The temperature must be exact, because we are working on a microscopic scale. Today, the machine is monitored by a computer that stops it automatically if the temperature changes. In the past, this had to be done manually, and our operator had to be constantly present. Our operator is currently the only person who can use these machines. We are looking for someone to assist him so that two people would know how to produce hairsprings. He learned the process from the previous head of the department.”

After flattening the wires, they are then cut and prepared for coiling. Four hairspring strips are inserted into a retaining frame that constrains their shape and allows them to be wound simultaneously. A technician completes around 200 frames per day, which equals 800 hairsprings. In this constrained state, the spirals undergo heat treatment. This thermal process is critical, as it stabilises the alloy, fixes the elastic properties of the spring and permanently sets its spiral geometry.

The four spirals are then separated from one another by vibration, meaning placed in a transparent case and simply shaken. This detaches the individual springs from the stacked configuration without deforming the coils.

A variety of oscillators produced at Precision Engineering, along with Moser’s signature modular escapement, which allows the entire regulating organ to be assembled and adjusted independently before being installed into the movement, reducing time spent in service

Subsidiary Assembly Room

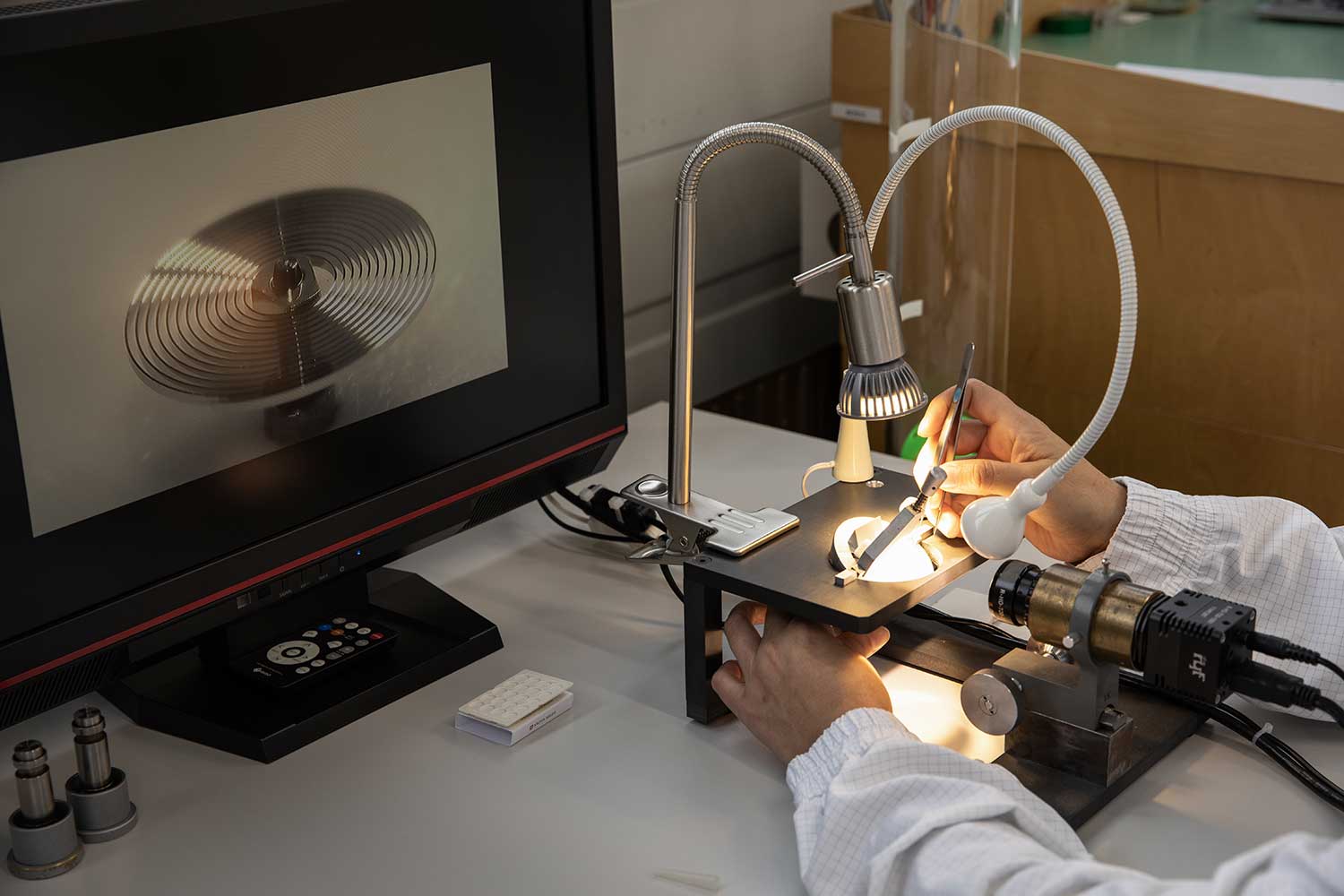

We were then brought into a room where, depending on the day, a range of sub-assembly work takes place, from fitting impulse jewels to safety rollers to assembling the modular escapement or the tourbillon with its cylindrical hairspring. On this occasion, the focus was on the forming of Breguet overcoils.

The hairspring is first sized. Coils are trimmed from the centre to create the opening for the collet, and the outer end is cut to establish the active length, defined by the number of turns and the terminal angle specified for the calibre. The inner end is then mounted on the collet in an operation known as virolage.

Attaching the hairspring to its collet, a small metal hub that fixes the inner end of the hairspring to the balance staff

Before any terminal shaping takes place, the hairspring undergoes flat truing and calibration. Its vertical and horizontal behaviour is examined, the motion is observed and the spring is adjusted until it lies perfectly flat. This step relies almost entirely on visual judgement and experience. The hairspring is then tested, a stage he noted had historically revealed issues, which explains why so many preparatory steps now precede it. As a result, rejection rates are very low, at around two percent.

The hairspring is also classified by strength so it can later be paired with a balance wheel of corresponding characteristics. A hairspring of one category cannot be combined arbitrarily with a balance of another. As Cedric explained, pairing the two incorrectly would be like fitting a powerful engine with inadequate brakes. Without this correspondence, precise regulation later on becomes impossible.

Once the hairspring is validated, the terminal curve is then formed by hand, either as a flat terminal or as a Breguet overcoil. This is the most delicate stage, as it determines how concentrically the spring breathes and therefore its isochronism. Forming a single overcoil can take around an hour, with minute corrections made to lift, curvature, and orientation.

“All our perpetual calendars are equipped with a Breguet overcoil. And when you see the blue balance bridge on an Endeavour, it is an indication of a double hairspring,” says Cedric.

Moser’s Straumann double hairspring is particularly demanding. It is an arrangement in which two identical hairsprings are mounted coaxially, one stacked above the other and angularly opposed by 180 degrees, so that gravitational errors acting on one spring are counterbalanced by the other. After drawing, rolling, heat setting and forming, every hairspring already sits inside an extremely tight tolerance band. For a single hairspring, that is usually enough, as small deviations in stiffness, elasticity or terminal behaviour can still be absorbed later during regulation.

With a double hairspring, however, each spring must fall not just within an absolute tolerance, but within a relative tolerance to another specific spring. Two springs may both be acceptable on their own and still be unusable together. Their spring constants must match and their mass distribution must be close enough that neither dominates once coupled. Sorting and pairing are hence positively brutal.

Machine room

From there, the tour moved into the machine room, where component manufacturing takes place. The operation is modest in scale, a far cry from the banks of CNC machines typical of mass-production luxury brands. Cedric explained that parts are produced in three different ways. The first involves CNC turning centres, sometimes combined with milling operations, where the workpiece rotates to allow the precise machining of round components such as gear blanks and balance wheels.

For larger components such as plates and rotors, Cedric showed us two CNC milling machines. One of them is a bit more manual, which he said, doesn’t help as there is little added value of someone manually changing the plate. The other is fully automated with a robot attendant, which was added the previous year. This system changes plates and tools automatically, eliminating frequent stops that were previously necessary when drills broke or different tools were required.

For much smaller components, they are cut by wire EDM. Thin metal plates are first pierced to create a starting hole, allowing a wire electrode to be threaded through, after which the component profiles are cut by erosion rather than by contact.

A didactic board illustrating the use of wire electrical discharge machining for ultra-thin steel components in the Perpetual Calendar calibre 341

Earlier, this was carried out using water as the dielectric, which limited surface quality. The installation of a newer oil-based wire EDM machine about a year ago dramatically improved the finish, producing surfaces clean enough to be left visible. This shift in surface quality is what allowed newer calibres to evolve from the more closed 200 series to the more open 201 and 202 architectures. Once these components are exposed, he noted, they must also be finished and decorated accordingly.

These manufacturing upgrades ultimately drive calibre evolution. Improvements in production methods, he said, directly affect finishing quality, even in very small details.

Final Assembly

Next, we were led into a final assembly room. On one bench sat a Vantablack dial being inspected. Cedric explained, “Several watchmakers attempted to work with it, but the problem, is that when you touch the microscopic structures made from carbon, they simply fall apart. It turns into dust, and what remains appears white. One of the brand’s chief watchmakers took on the challenge and eventually found a way to stabilise the material.”

Moser’s Vantablack dial is coated with a forest of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes that absorb more than 99.9% of incoming light. Photons entering the structure are repeatedly trapped and dissipated between the nanotubes rather than reflected back to the eye, producing an almost total absence of visual depth

When the watch was unveiled, he recalled, some industry peers assumed it could not be genuine, believing such a result to be impossible. For the brand, this reaction was itself the achievement, emblematic of a broader ambition to push boundaries and to question long-accepted assumptions about how watches can be made and presented.

From there, we were introduced to one of the manufacture’s most experienced watchmakers, who works on complications. He was working on the perpetual calendar, which comprises between 290 and 310 components. At first glance, he noted, the movement may not appear especially complex because the display has been simplified, but the work involved is highly demanding.

Because of this, he does not work on many movements at the same time; typically five at once when delivery timelines are tight, or up to ten when there is more time available. He performs the same operation across each set before moving on to the next step. At the moment we observed him, he was at the final stage, setting the date display which consists of two discs stacked on top of each other – one covering days 1 to 16, and the other covering days 16 to 31. Cedric said, “In the past, we took over 100 hours to assemble a perpetual calendar. Today, we’re talking about 20 hours. It was a team effort from watchmaker to construction to optimise the movement and the process”

Originally developed by Andreas Strehler, the perpetual calendar is distinguished by a crown-only adjustment system that allows all indications to be advanced both forwards and backwards, with no dead time, and with an instantaneous date change. Cédric explained that when the brand develops a new complication, significant investment is always required, which entails working with external complication specialists.

In 2023, however, MELB Luxe acquired a stake in Agenhor, a move that gives the group direct, long-term access to one of the most inventive complication ateliers in watchmaking. This allows complex mechanisms to be developed in closer dialogue with Moser’s own engineers and watchmakers. The first complication they undertook was the ingenious double retrograde Chinese Calendar, before turning their attention to a more accessible offering in the form of the Pioneer Retrograde.

The Endeavour Chinese Calendar combines the Gregorian and Chinese calendars, using cams to manage the irregular structure of the Chinese lunisolar system while presenting its indications with unusual clarity

What stands out throughout the tour, particularly for an independent, is the consistency of its practical, almost disarmingly rational approach. Decisions are repeatedly grounded in clear assessments of what works best, with choices made in the service of reliability, efficiency and long-term durability. Ambition is evident, but it never drifts into overreach, because it is supported by mature technical foundations and a disciplined way of thinking and making that keeps invention tethered to repeatability and reliability. This is an approach more commonly associated with large industrial manufactures than small independents, and it goes a long way toward explaining why Moser’s watches are robust and reliable, even as they remain unmistakably fine watches.

As the company’s momentum continues to build, its present premises are already being pushed beyond their intended limits. The response is a new, larger facility, now under construction and due for completion in 2028. Set within the city itself and looking out over the Rhine Falls, it is a natural evolution first and foremost, but also a telling one. It offers the space required for growth, and a view that seems to acknowledge an ambition to play on an even larger stage in modern watchmaking.

H. Moser & CIE.