Reference

Complete Guide: Patek Philippe’s Modern Chronographs

It is particularly when faced with a tabula rasa, a codex wiped clean, that the Stern family have excelled in their creativity. Time and again when given the opportunity to define a new watch or propose a new movement, invariably, a new era is created. Remember that it was only a mere nine years after they took the helm of Patek Philippe that the Stern family created the two most important complicated watches of the 20th century: the 1518 perpetual calendar chronograph and the 1526 perpetual calendar. Both watches were unveiled in 1941 while the world was in the throes of the Second World War. Together, they introduced us to the modern era of the complicated wristwatch. But, in every way, these two watches were the result of a tabula rasa. The Stern brothers (Charles and Jean Stern), in essence, started from a blank slate and using nothing more than their imagination; in an act of seismic creativity, they defined the prevailing aesthetic and technical language of 20th-century modern horology. Nearly half a century later — in 1989 — on the occasion of the maison’s 150th anniversary, Philippe Stern would reconnect a world fully recovered from the ravages of the Quartz Crisis with a renewed faith in complicated mechanical watches by launching the record-setting caliber 89 and, once again, a new era was defined.

An exceedingly rare stainless-steel Patek Philippe ref. 1518, an example of Patek Philippe's first serially produced chronograph perpetual calendar launched in 1941 and discontinued in 1954) (Image: John Goldberger)

1941: Patek Philippe’s first series-produced perpetual calendar wristwatch, the Ref. 1526, also established the company’s signature dial layout of two apertures and a central subdial. This model was 34mm and fitted with the hand-wound calibre 12-120 QP

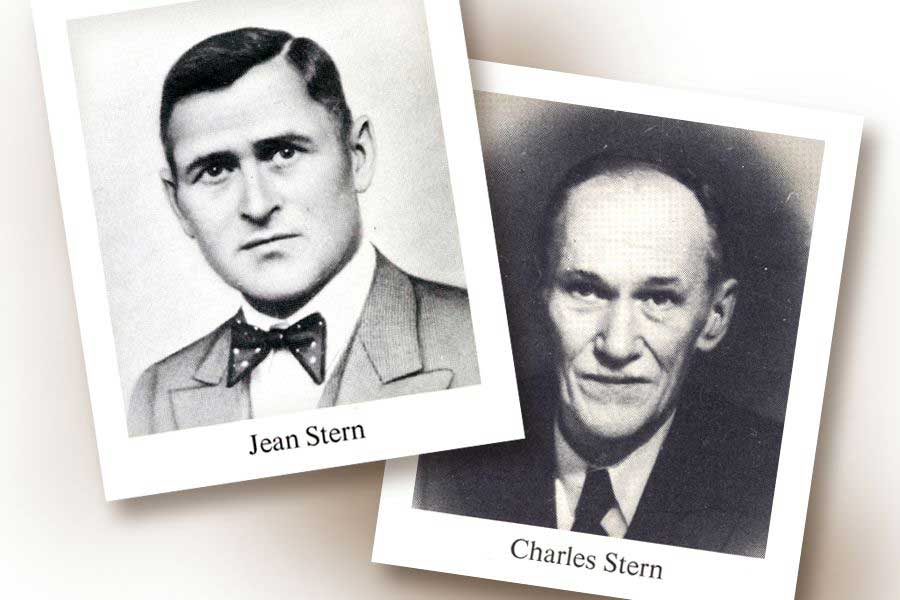

Brothers Jean and Charles Henri Stern, defined the prevailing aesthetic and technical language of 20th-century modern horology with the launch of the 1526 Perpetual Calendar and the 1518 Perpetual Calendar Chronograph

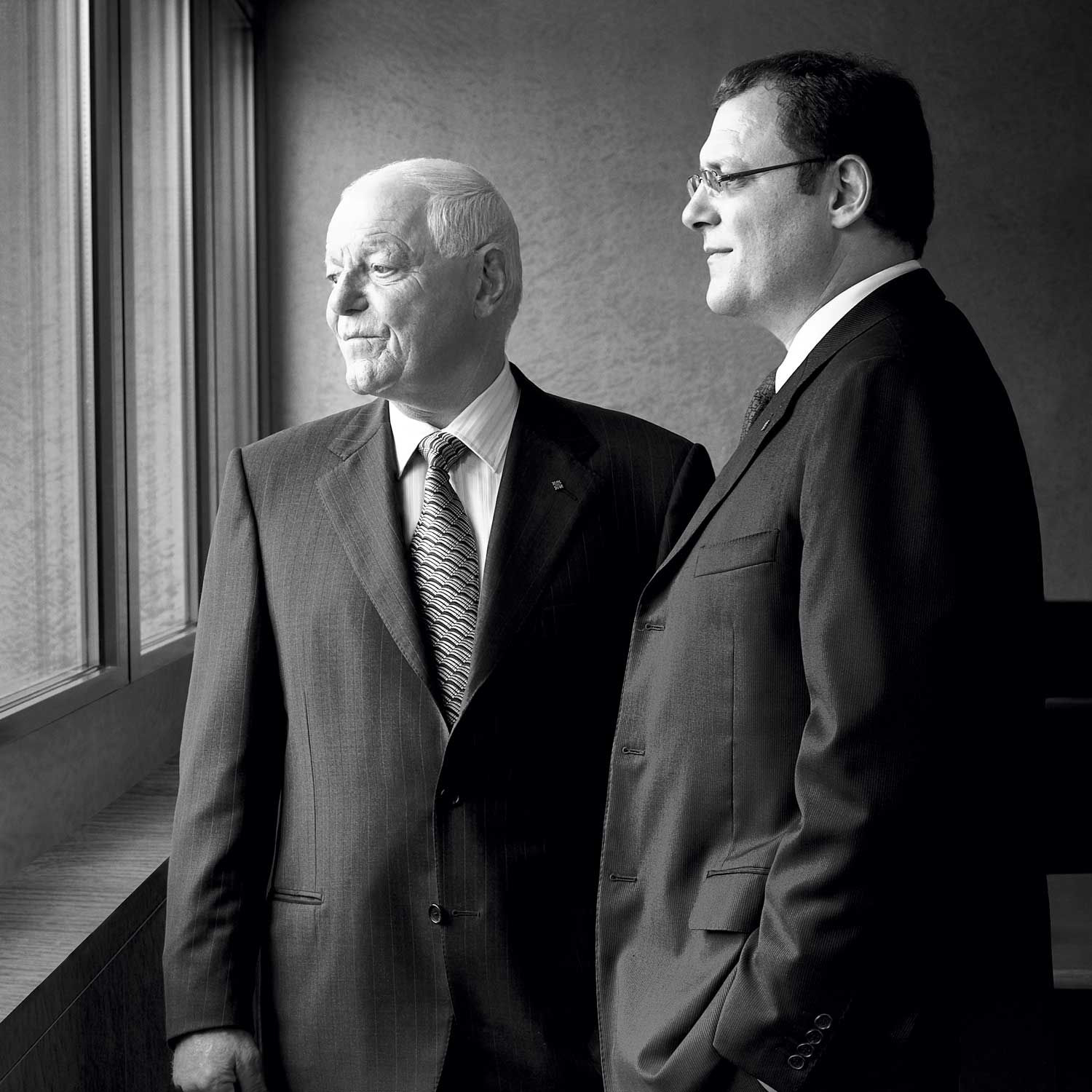

Father and son duo, Philippe and Thierry Stern at the Patek Philippe manufacture

Patek's take on the Lemania 2310 movement in the ref. 3970, renamed the Cal. CH 27-70 Q was introduced in 1985 (Image: sothebys.com)

Launched in 2009, the Patek Philippe CH 29-535 PS

The CH 27-70

Looking at the history of the manual-wind chronograph at Patek Philippe until 2009, you might be surprised that there have only been three movements that have powered almost a century’s worth of watchmaking icons. The first is the caliber 13-130 based on the Valjoux caliber 13. The second is the caliber 13 based on an ébauche by Victorin Piguet which was used, in particular, in many of Patek Philippe’s split-seconds chronographs and even powered some very early examples of the reference 130, including the magnificent steel-cased no. 198073, featured in John Goldberger’s iconic tome Patek Philippe Steel Watches. As an aside, the “13” in the name of both calibers refers to 13 lignes, which is the equivalent of 29mm and is the diameter of both movements.

Early Patek Philippe ref. 130 steel chronograph powered by a Victorin Piguet ébauche and in a monopusher configuration, instead of the Valjoux-based movement found in the majority examples of 130 (Image: John Goldberger)

The 2310 was introduced in two versions: the CH 27-17P two-counter version (seconds and chrono minutes) and CH 27-12P three-counter version (seconds, chrono minutes and hour totalizer). Adding to the complexity, the movement came in a 17-jewel version (which formed the base of the Omega 321) and also a 21-jewel version with swan-neck regulator known as the Lemania 2320. The movement’s vibrational speed was 2.5 hertz or 18,000 vibrations per hour. Each of Patek’s movements was based on an ébauche (a blank movement kit) selected by the Stern family for its combination of reliability and potential for beauty when transformed by Patek, who applies a dizzying array of transcendent finish to it.

Patek's take on the Lemania 2310 movement in the ref. 3970, renamed the Cal. CH 27-70 Q was introduced in 1985 (Image: sothebys.com)

Following the recovery from the Quartz Crisis, in the ’80s, the Lemania 2310 became a canvas of expression for watchmaking’s most revered maisons, which would ultimately include Vacheron Constantin, Breguet and Roger Dubuis. But the first and predominant among these was Patek Philippe. Philippe Stern first used the CH 27-70 in 1985 to replace the Valjoux 13-130 of the 2499 and create the amazing 3970 perpetual calendar chronograph.

Thanks to the Lemania 2320’s 27mm diameter, Stern was actually able to make a smaller watch at 36mm in comparison to the 2499’s 37.5mm diameter. In 1994, the CH 27-70 was used to create the single most iconic perpetual calendar split-seconds chronograph — a Holy Grail of watch collecting — known as the Patek Philippe 5004. Four years later, in 1998, the chronograph movement would also power the ref. 5070. This remarkable watch was the largest Patek chronograph ever serially produced at 42mm and was based on an oversized pilot’s chronograph displayed in Patek’s Geneva museum. Finally, the CH 27-70 was used in the successor to the 3970, the larger 40mm 5970, designed by Thierry Stern and launched in 2004. Incidentally, the 5970, to me, is the single most beautiful perpetual calendar chronograph ever created. Patek finally stopped using the hallowed CH 27-70 in 2011 when it was replaced by the in-house 4Hz caliber CH 29-535 PS.

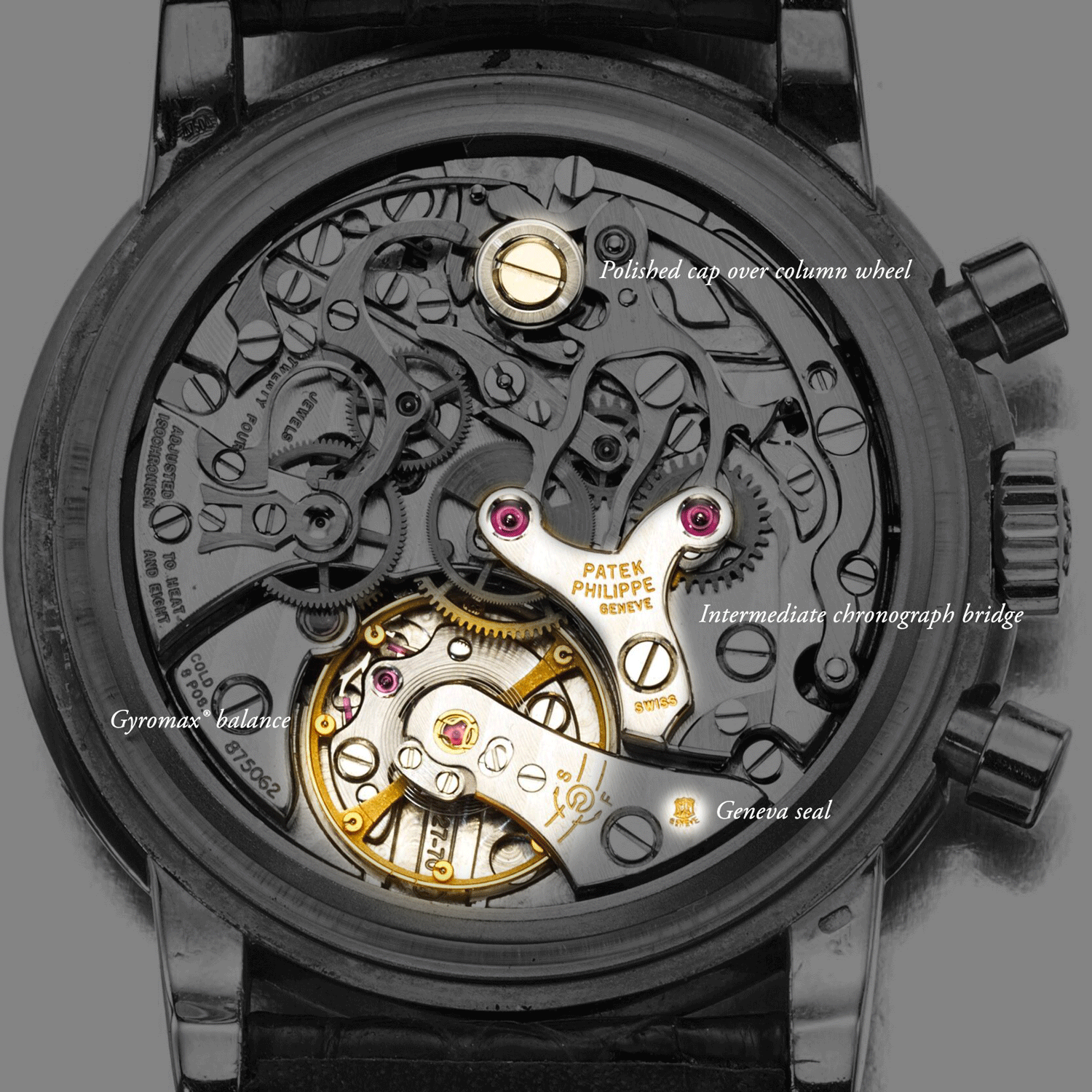

A caseback view of the Patek Philippe 5004, showcasing the Lemania-based CHR 27-70Q (Image: sothebys.com)

As such, it is highly conceivable that as he scoured the industry for an engine for his perpetual calendar chronograph, he quickly realized he was limited to what was available. The Quartz Crisis of the 1970s had all but decimated the Swiss mechanical watchmaking industry. Movements had been sold by the weight, while machines used to create them had been callously discarded to make way for new technology at the height of the panic. It is therefore very probable that even if he had wanted to use the Valjoux caliber 13, which formed the base of the caliber 13-130 that powered both the 1518 and 2499, it was not being made anymore. And so he zeroed in on the Lemania 2310, which had somehow survived the widespread culling and which he knew was both extremely reliable, as demonstrated by its association with NASA, and had the capacity to be transformed into a work of dazzling horological beauty. It must be said that, to my mind, the Patek caliber 27-70 is the single most beautiful classic chronograph movement of all time, and even when compared to similar movements from other brands, the finish and design of the components such as the chronograph bridge or the coupling lever are unrivaled in their majesty.

Patek Philippe Cal. 89, packed with 33 stellar complications for the maison's 150th anniversary

To learn more about the Lemania 2310, please check out our comprehensive story, here.

The Ref. 5070 Manual-wind Chronograph

At 42mm, the reference 5070 could only be called an act of horological audacity. And rightly so, because after a near 40-year absence — the last Patek chronograph-only watch was the reference 1463 which was discontinued in the ’60s — it signaled Patek Philippe’s return to once again become the dominate producer of the gentleman’s chronograph, albeit, in this case, a watch of very bold proportions. Says Thierry Stern, “The inspiration for the 5070 comes from a unique oversized 46mm pilot’s split-seconds chronograph that is on display at our museum in Geneva.” Patek neophytes sometimes mistake the 5070 as emerging from the period of oversized watches that dominated the first decade of the new millennium. But that would be incorrect. The 5070 was launched in 1998. Remember that the Panerai brand was only launched by Richemont Group at the 1998 Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie and it would take several years before the trend for large-sized watches would predominate even in dress watches. In order to have launched the incredible 5070 in 1998, Philippe Stern would have already conceptualized and designed this exceptional oversized timepiece many years before.

In comparison to the reference 3970 or the 5004 launched, respectively, in 1985 and 1994, both at 36mm in diameter, the 5070 — a full 6mm larger in size — seems like a wild, almost libidinous departure. But, in fact, the oversized chronograph has always been a tradition at Patek Philippe. For example, in 1937, just one year after the launch of the 33mm-diameter reference 130 — the very first gentleman’s chronograph watch made in series — Patek Philippe launched the reference 530, which was 3.5mm larger in size at 36.5mm. To understand this, you have to bear in mind that in the context of the 1930s, there is no such thing as a sports watch. Indeed, to create a watch that was suited to sporting purposes, such as for the burgeoning worlds of aviation or auto racing, you would simply create a larger version of an existing watch to enhance visibility when you were in the cockpit with engine vibration obscuring your vision. This is perhaps best exemplified by the legendary Patek chronograph delivered to gentleman racing legend Count Carlo Felice Trossi in 1932 which measured a staggering 46mm in diameter. It is a wonderful image to conjure up of Trossi calculating his average speed behind the wheel of his famous Ferdinand Porsche-designed Mercedes SSK which he bought in 1933, a year after he had received his equally legendary Patek chronograph.

The yellow gold, black dial ref. 2512 split-seconds chronograph that Patek Philippe bought at a Christie's auction in 2000 for the Patek Philippe Museum; this execution of the 2512 inspired the modern day ref. 5070 launched in 2008

Patek Philippe Ref. 5070J-001 (Image: phillips.com)

Patek Philippe Ref. 5070G-001 (Image: phillips.com)

Patek Philippe Ref. 5070R (Image: phillips.com)

Patek Philippe Ref. 5070P-001 (Image: phillips.com)

What is also interesting is that both the references 2512 and 5070 faced the same design challenge, which was how to take a smaller chronograph movement and design a very big chronograph with a dial that feels balanced. In the 2512, this was the caliber 13-130 based on the Valjoux caliber 13, which measured 13 lignes or 29mm; and in the 5070, it was the caliber CH 27-70 based on the Lemania 2320, which measured 27mm in diameter. The issue, of course, related to the placement of the pinions for the chronograph minute hand and the continuous seconds hand, which, when placed in an oversized case, can suffer from a “cross-eyed” syndrome where their corresponding subdials feel like they are too close together.

The yellow gold with bronze dial ref. 5070J-012 made for the 2015 London Grand Exhibition, limited issue of 5 pieces (Image: acollectedman.com)

The platinum with blue dial ref. 5070P-013 made for the 2015 London Grand Exhibition, limited issue of 5 pieces (Image: acollectedman.com)

The white gold with salmon dial ref. 5070G-014 made for the 2015 London Grand Exhibition, limited issue of 5 pieces (Image: michaelashtonwatches.com)

The design genius of the 5070 is the use of what are, essentially, circles that radiate outward from the center of the watch that each become a defined segment of the design real estate. First, there is the inner part of the dial featuring the applied Arabic numerals. This is followed by the tachymeter. Then, the seconds track in bold chemin de fer (or railroad track) style. Then, the bezel and, finally, the shape of the case. Together, these circles create the effect of ripples radiating on a pond, resulting in a dynamic but very harmonious effect. Incidentally, this is also a design code that Thierry Stern would use when he designed the 5970. The 5070 was only the second water-resistant chronograph created by Patek Philippe and occupies a very special place in the hearts of collectors for its unusual and, literally, larger-than-life allure.

The Tabula Rasa — CH 29-535 PS

I always find the pragmatism with which Patek names its movements amusing in that they are simple, unemotional descriptions of their height and girth. If we were to name human beings in the same way, I would be Mr. Five-foot-nine — 175 pounds. Accordingly, the CH 29-535 gets its name from its dimensions, specifically, 29mm in diameter and 5.35mm in height. It is, however, not Patek Philippe’s first in-house chronograph movement. That honor belongs to the automatic vertical-clutch-driven caliber CH 28-520 found in the annual calendar chronograph reference 5905. But it is important to understand that this movement was conceptualized as an altogether different animal. With its automatic-winding function, column-wheel-activated vertical clutch and silicon hairspring, escapement wheel and escapement lever, it was created from the ground up to be Patek Philippe’s high-performance, ultra-robust sports watch chronograph movement. In comparison, the creation of the manual-wind, laterally coupled CH 29-535 movement was a work of horological elegance rather than the exercise in pure performance that was the CH 28-520. If you want an analogy, the CH 28-520 is comparable a 118-foot WallyPower yacht while the CH 29-535 can be likened to the world’s most elegant sailboat.

Patek Philippe’s first in-house chronograph movement is the automatic vertical-clutch-driven caliber CH 28-520 found in the annual calendar chronograph references such as, the ref. 5905

The CH 29-535 also features a precise jumping minute counter. This is a chronograph minute counter that jumps forward by one minute only at the precise moment the chronograph seconds hand passes the 60-seconds mark. In other chronographs, the minute counter hand creeps forward incrementally or, if it does jump, can take one to two seconds to complete this motion. A precise jumping minute counter requires the addition of a complex mechanism comprising a snail cam attached to the seconds wheel, a ruby feeler that rests on the cam and that falls off the edge of the cam each minute, activating a minute counter lever to pull the chronograph minute wheel precisely. While the first and only other manual-wind chronograph movement to feature this added complication is the Lange Datograph, Patek’s approach to their precise jumping minute counter features both a completely redesigned snail cam profile as well as an oversized spiral spring used to power the chronograph minute lever, which exerts less spring tension and thus transmits less friction to the snail cam. As a result, the system in the CH 29-535 PS places far less load on the movement.

The Patek Philippe CH 29-535 is one of a handful of chronograph movements with a precise jumping minute counter

Six Patents for the CH 29-535 PS

Looking lower down on this bridge you will see first one ruby on the left just below the “PP” shield of the Patek Philippe Seal. It is on this jewel that the chronograph minute wheel lever, which features the feeler that rests on the snail cam as well as the pawl that pulls the chronograph minute wheel forward, is set. Further down at the bottom of this bridge, you will see another jewel that retains the spiral spring that provides the spring tension for the lever. The architecture is complemented by a muscular balance cock for the movement’s free-sprung balance beating at 4Hz. The bridge on the far left of the movement retains the seconds wheel or fourth wheel, which in turn powers the chronograph drive wheel, which sits on a jeweled pinion on the S-shaped chronograph lever. Underneath this lever, a long feeler, along with the feeler for the brake and the reset hammers of the chronograph seconds wheel and the minute counter, rests against the all-important column wheel. Above this, the S-shaped chronograph lever ends in a long attenuated arm that rests against the eccentric cam that sits on top of the column wheel. By turning this cam, you adjust the depth of the engagement for the chronograph lever.

Says passionate Patek collector Ahmed “Shary” Rahman who owns both the 5270 perpetual calendar chronograph and the 5370 split-seconds chronograph, both based on the CH 29-535 PS, “When you understand all the functional innovations represented by the movement, you appreciate its architecture even more. What you at first regard as a work of aesthetic beauty is now endowed with a language where form and function merge in a wonderfully poetic way. To me, this is the magic of Patek and the magic of the CH 29-535 PS. Everything has a purpose; nothing is superfluous. There is always a raison d’être.”

Shary's ref. 5370P, in platinum with black enamel dial, which has been discontinued since July 2020 (©Revolution)

Ahmed "Shary" Rahman, seen here with the Patek Philippe ref. 5370P on his wrist (©Revolution)

Caseback of Shary's ef. 5370P, in platinum powered by the CH 29-535 based CHR 29-535 movement (©Revolution)

The Ref. 7071 Ladies First Chronograph

From left, the various executions of the 7071 and their production years: Rose gold, gem-set with silver dial, 2010–2017: rose gold, gem-set with black dial, 2010–2017; white gold, gem-set with silver; dial, 2012–2017; white gold, gem-set with gray dial, 2012–2017; white gold, gem-set with blue dial, 2012–2017

1968: Patek Philippe creates the first Swiss wristwatch, made for Countess Koscowicz of Hungary

Patek Philippe launched the ref. 4864 Travel Time in 1992, powered by the cal. 215 PS FUS 24H (Image: sothebys.com)

The Patek Philippe Ref. 7071R-001, powered by the CH 29-535 (Image: christies.com)

Cushion-shaped-case chronographs at Patek have normally been reserved for its more complicated and rare watches such as the reference 5950 split-seconds chronograph in steel or the reference 5050 “TV Screen” perpetual calendar chronograph. So you could make the argument that Patek wanted the 7071 to feel very special. And for good reason because it represented the very first home for its all-new in-house manual-wind chronograph caliber, the CH 29-535 PS. And while many people remarked on the watch’s charm and how it represented a beautiful and sincere expansion of the role of complicated women’s watches at the world’s most revered manufacture, the true connoisseurs could only marvel at the movement within the watch with an understanding that it had just ushered in an all-new era of the manual-wind chronograph at Patek. Immediately, the speculation about the first men’s watch to feature this movement abounded. But we would have to wait a full agonizing year before this was unveiled.

The Ref. 5170 Manual-wind Chronograph

To think of the sublime and subtle reference 5170 as the heir to the big and bold reference 5070 is to miss its intentions entirely. Instead, we have to once again consider the Stern family’s acute ability to understand the prevailing moral values of the time. In 2010, the world is just recovering from the global financial crisis of 2007/2008. But more importantly, there has been a shift back to classicism. We see this in a renewed interest in classic elegance and sartorialism; there was a distinct shift away from the trends in the earlier part of the millennium and we see this, in particular, in watch tastes. While the watch industry in the first decade of the 2000s was driven largely by the idea of extroverted watchmaking and characterized by a growth in case sizes to dimensions that are verging on unwearable and the heaping of every known visible complication onto transparent or even nonexistent watch dials to create what are termed “hyper complications,” Patek was the first to realize a resurgence in understated, modulated and discreet elegance. And the reference 5170 is the perfect expression of all of these qualities, making it the successor, not of the sporty and decidedly racy reference 1463 “Tasti Tondi,” but the magnificent tranquility of the reference 130, the watch that started it all, back in 1936.

Similarly, the ’30s following the worldwide economic depression was a period of measured discretion in contrast to the exuberance of the Roaring ’20s. This was all perfectly expressed by the reference 130 which, at 33mm, was the classic size for a gentleman’s chronograph. There is nothing aggressive or “shouty” about the reference 130; from its wonderfully smooth Calatrava-style case to its discreet square pushers, all 1,500 examples made between 1936 and 1964 exhibit the graceful, lithe, attenuated charm of a classic beauty, like Catherine Deneuve, Audrey Hepburn or Grace Kelly. In the context of its launch in 2010, this is precisely the motivation for the wonderful reference 5170.

Patek Philippe launched the Ref. 5170J in 2010 as the first chronograph to be powered by their in-house designed calibre CH 29-535 PS (Image: Phillips.com)

The 2010 Patek Philippe Ref. 5170J's dial is the only one in the reference to feature a combination of Roman Numerals and baton hour markers with a pulsation chronograph scale (Image: Phillips.com)

Caseback view of the 2010 Patek Philippe Ref. 5170J showcasing the calibre CH 29-535 PS (Image: Phillips.com)

It is Zen reductionist, or minimalist perfection, at its very best. The crown and square pushers have the same balanced proportions of the reference 130, while the dial uses a beautiful, decidedly vintage style of typography that’s also reminiscent of the reference 130. Even the surface decoration of the dial is kept uniform throughout the watch, making it the apogee of calm, meditative tranquility with softly sunken subdials.

Patek did, of course, bestow us with the gift of its wonderful applied Breguet numerals, which take center stage in the most collectable versions of the reference 130. In most cases, I am a fan of tachymeters and all forms of scales on chronographs. I am still waiting for a brand to make a watch with a Negroni-meter to time how long it takes me to quaff my favorite beverage. But, somehow, in the reference 5170, my favorite versions of the watch are those without scales, in particular the black-dial Breguet-numeral version in a white-gold case. And, of course, there is the ravishing platinum version with a blue dial and diamond indexes, which still somehow manages to remain charmingly discreet.

The Ref. 5170G-001 was launched in 2013; this second version of the watch featured a white gold case with applied Breguet hour markers and a pulsation scale (Image: Phillips.com)

The Ref. 5170G-010 was launched in 2015; this second version of the watch featured a white gold case with applied Breguet hour markers on a black dial, devoid of a specialty chronograph scale (Image: Phillips.com)

The Ref. 5170G-010 was launched in 2015 was powered by the calibre CH 29-535 PS (Image: Phillips.com)

The Ref. 5170R-010 was launched in 2016 alongside the white dial version, the Ref. 5710R-001; this generation of the watch had a rose gold case with applied Breguet hour markers (Image: Christies.com)

In 2017, Patek Philippe launched the Ref. 5170P-001, the concluding generation of the reference in platinum with a blue dégradé dial featuring diamond baton markers and a tachymeter scale

From left, key executions of the 5170 and their production years: Yellow gold with Roman Numerals 5170J-001, 2010-2014; White Gold with Breguet numerals 5170G-001, 2013-2016; Rose Gold with Breguet Numerals 5170R-001, 2016-2018; Platinum with Diamond Hour Markers 5170P-001, 2017-2019

The Ref. 5270 Perpetual Calendar Chronograph

In 2011, an important transition happened for Patek Philippe. It bid adieu to the much-beloved CH 27-70 powered 5970 and introduced the 5270, the very first Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronograph in the brand’s history to be powered by an in-house movement. There were two factors underlying this.

The first was that Swatch Group owner Nicolas G. Hayek had long publicized his intention to stop delivering movements to brands outside of the group. The second was Philippe Stern’s long-term objective to achieve full independence in manufacturing. The latter was clearly the impetus behind his creation of Patek Philippe’s incredible manufacture in Plan-les-Ouates, which, as of 2020, has had a major extension.

It was behind his push into silicon escapement components, which freed him of reliance on Swatch Group-owned Nivarox. It was the motivation behind the creation of the in-house, laterally coupled column-wheel chronograph movement, the CH 29-535 PS. Says Thierry Stern, “The advantage to the CH 29 is that it was designed from the ground up to function with a perpetual calendar, as with the 5270, or even a perpetual calendar as well as a split-seconds function, as we offer with the 5204. In comparison, we had to reverse-engineer the capacity to have these functions with the CH 27-70.”

The 5270 Perpetual Calendar's first generation, Ref. 5270G-001 was launched in white gold, in 2011 and then discontinued in 2017; this early version of the watch did not have a tachymeter scale and was discontinued in 2013

2013 version of the Patek Philippe ref. 5270G, the 5270G-013 with the infamous "chin" and tachymeter scale on the watch dial, this second version of the white gold 5270 was discontinued in 2015

2013 version of the Patek Philippe ref. 5270 in white gold with the blue dial, still with the infamous "chin" on the watch dial

A rose gold version was added in 2015 with the 5270R-001 and discontinued in 2018, sans "chin"

The white gold white dial 5270 was also updated in 2015, sans "chin", with the Ref. 5270G-018

The white gold blue dial ref. 5270 was also updated in 2015, sans "chin" with the ref. 5270G-019

The Ref. 5270P-001 platinum 5270 introduced in 2018 with the salmon dial

The Ref. 5270/1R-001 rose gold 5270 introduced in 2018 with the integrated full gold bracelet

The Patek Philippe 5270J-001 is the 5270 Perpetual Calendar Chronograph for the first time ever in yellow gold (©Revolution)

Launched in 2020, the 5270J-001 takes after the 3rd generation dial design of the 5270 with the integrated tachymeter and seconds track on the outer perimeter of the dial (©Revolution)

Tthe 5270J-001 like all of its predecessors is powered by the Caliber CH 29-535 PS Q (©Revolution)

Say Thierry Stern, “I love perpetual calendars, but the irony is when you get to the stage in life when you can own one, sometimes your eyesight is not the best. During the design of the 5970, I even experimented with using a loupe or a magnifier over some of the displays. As such, when it came to the 5270, I wanted to create a design that was as clear and visible as possible.” This is clearly evinced in the larger case size and more open dial. It is also part of the rationale for the subdials of the CH 29-535 PS being lower on the dial, significantly beneath the horizon line created by the crown.

Says Philip Barat, Patek’s head of watch development, “When Thierry was working with us on the movement, he explained he wanted to enlarge the displays for the month and the day at 12 o’clock, and so we shifted the subdials slightly lower on the movement to afford more space on the upper half of the dial.” The other reason for the subdials of the 5270 sitting a bit lower on the dial relates to the precise jumping minute counter. Because this counter necessitates an additional mechanism, specifically the minute counter lever and spring, the subdials need to shift either lower or higher on the dial to make room for this mechanism, depending on the orientation of the movement. If you check the position of the subdials of the Lange Datograph, the only other manual-wind chronograph with a precise jumping minute counter, you will see that they are also positioned slightly lower on the dial.

But back to the design of the Patek 5270. One of the most appealing elements of Thierry Stern’s design for the hallowed 5970 relates to the flared and faceted lugs, which add a provocative and alluring dimension to the case. For the 5270, Stern upped the ante on the lug design by combining an even more exaggerated flare and facet for the lugs with an added step. The results are the single most dynamically stylized lugs of any Patek chronograph since the famous spider-lug chronograph, reference 1579. Looking at the watch, you cannot miss the lugs, and the difference between these and the lugs of the 5170 is as significant as the wheel arches between a standard Porsche Carrera and those on an Akira Nakai Rauh-Welt Begriff (or “Rough World” Concept) modified Porsche 930 Turbo. Thanks to them, the 5270 is given an aggressive and almost predatorial stance that I associate with Mike Tyson’s trapezoids in his prime. These lugs are complemented by the thicker, more aggressively raked bezel that contrasts with the thinner, more concave unit found on the 5970.

The case of the 5270 has a set of exaggerated flared and faceted lugs with an added step, compared to the ones on the 5970 (©Revolution)

The resultant design on the 5270's lugs is the single most dynamically stylized lugs of any Patek chronograph since the famous spider-lug chronograph, reference 1579 (©Revolution)

Over the decade-long history of the 5270, we have seen an interesting design evolution to the watch. The first series watches which were made from 2011 to 2013 have the cleanest dial design in that they have no tachymeter scale, and the circumference of the dial is defined with a nice chemin de fer seconds scale. While they are lovely watches, to me, the aggressive sportiness of the 5270 works better with a tachymeter. The second series watches made between 2013 and 2015 now have a tachymeter (but no seconds scale) and is configured with what collectors refer to “the chin.” In these watches, the date indication protrudes visibly into the tachymeter to create this chin-like effect. In 2015, Patek launched the third series of the 5270; this time, with the most beautiful and balanced dial, which featured a seconds track as well as a tachymeter that merged seamlessly with the date indicator, as per the design of the 5970.

In 2018, two major design achievements came the way of the 5270. The first was what has been universally applauded as one of the most stunning perpetual calendar chronographs of all time — the platinum model with a salmon dial and Arabic indexes known as the 5270P-001. This is interesting, particularly because Arabic indexes have been used very rarely on this complication, appearing most notably in the 5004 split-seconds chronograph perpetual calendar in certain configurations, the 2499 first series watches and the 1518. Add to this the rarity of a salmon dial and to say that this watch will be a future collectable is something of an understatement.

But, that same year, Patek Philippe also released a rose-gold, black-dial version of the 5270 with one of the most desirable elements in Patek collecting culture — an integrated factory bracelet. Wearing a Patek Philippe perpetual calendar chronograph/split-seconds chronograph on a bracelet was popularized by none other than Eric Clapton, who frequently ordered his pièce unique 5970s and 5004s with their signature Breguet “12” on matching metal brick bracelets. Here is an image of a white-gold 5970 in that exact configuration that was once owned by the guitar hero known by the evocative sobriquet “Slowhand.” The thing was, an integrated bracelet perpetual calendar chronograph was something that Patek would only provide for very special customers. That was, until Thierry Stern introduced the 5270/1R, which not only came replete with a coveted rose-gold bracelet, but the pushers for the calendar correction had also been integrated into end-links of the bracelet for the first time in Patek’s history. These two watches represent some of the most brilliant, ravishing and, to my mind, collectable Pateks of the modern era.

If you want to read more about the Patek 5970, you can check out my story, here.

Or, famed journalist Nick Foulkes’ story on the 5970, here.

The Ref. 5204 Split-Seconds Perpetual Calendar Chronograph

It was during this lunch that he recounted all the numerous challenges Patek had in the creation of a split-seconds version of the CH 27-70. If you think about it, there has never been any other watch in history to use a split-seconds version of the Lemania 2310 ébauche. And that was for good reason, in that the movement was never meant to incorporate this feature. Of course, later, Breguet would create its own version of a split-seconds 2310-based chronograph, but that was only after Patek had made the 5004 and, in so doing, exposed one of the movement’s weakness and shown the way to overcome it.

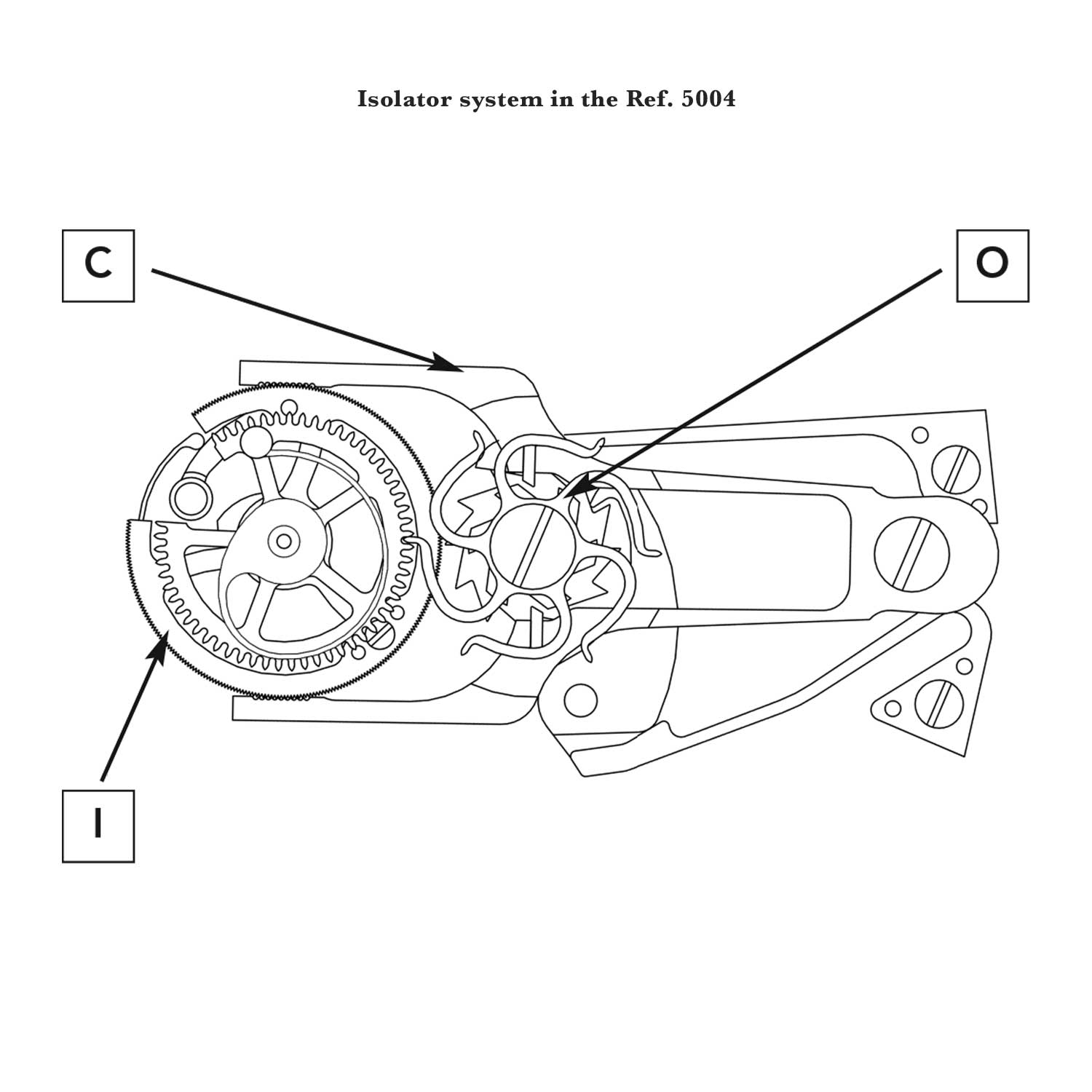

OK, it goes like this. A laterally coupled chronograph is already a parasitical device, meaning that when activated, it consumes power from the base movement. But when you add a split-seconds mechanism and when the split function is activated, you get a further drop in power and diminishment of the balance’s amplitude, because the mechanism that allows the split hand to catch up with the running seconds hand is creating drag. This consists of a ruby roller attached to a lever that is under spring tension. In order to eliminate this drag, Patek Philippe created a special isolator system which is nicknamed “the Octopus” by collectors for its resemblance to the multi-tentacled sea creature. This device lifts the reset lever off the split-seconds heart cam that is attached to the chronograph wheel. As Philippe Stern explained during our lunch, “Without this, the 5004 would never work properly.”

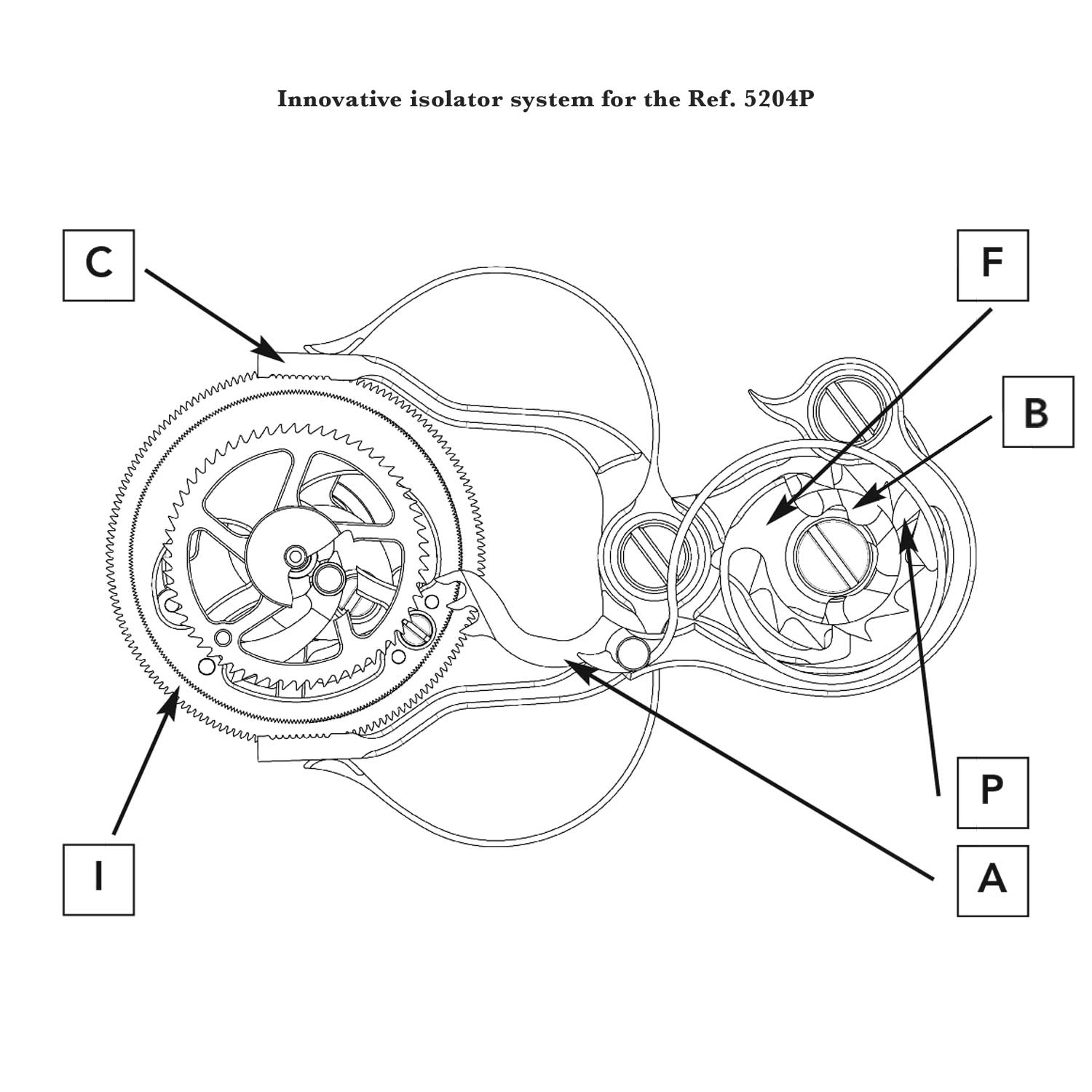

The isolator for the split-seconds lever relies on an isolator wheel that is driven by an octopus wheel (O) (isolator wheel / splitseconds spring wheel) on the split-seconds column wheel and uncouples the split-seconds lever as soon as the split-seconds clamp (C) closes. Because the octopus wheel consistently rotates in the same direction, it always has to be returned to its home position together with the split-seconds lever; this is done by the isolator wheel spring as soon as the split-seconds clamp opens again.

One of the things I’ve always suspected about the CH 29-535 is that, knowing Patek Philippe, I would not be surprised if the movement has adequate torque to power both the 5204’s perpetual calendar displays and its split-seconds function with negligible effect on the balance’s amplitude, especially at a full state of wind. But I love the fact that they decided to create an isolator mechanism for the split-seconds function anyway. To me, this is an example of the slavish lengths to which Patek will go to ensure the perfect function of their watches and also, in a big way, pay homage to the Octopus, which has become a symbol of their technical innovation and ingenuity.

Now, it is important to understand that at the time of the 5004’s launch in 1994, the Octopus was ground-breaking technology. There are two main springs in the Octopus’ isolator system. The first is the spring for the split-seconds brake, which allows its clamping function. The second is the isolator wheel spring that sits on top of the split-seconds wheel and necessitates a good bit of extra height. Now, this is the important part. The springs of the isolator wheel and the springs of the split-seconds brake act in opposite directions. That’s because the Octopus rotates in just one direction. When the clamp of the split-seconds brake opens, the Octopus wheel has to rotate to its home position, which is done by the isolator wheel spring. Which means that it has to overcome the force of the split-seconds brake spring.

So when approaching the isolator mechanism of the new 5204, Patek went back to the drawing board. And the first thing they did was get rid of the isolator wheel spring mounted on the split-seconds wheel. Instead, they ingeniously integrated this spring as part of the split-seconds column-wheel cap. The second thing they did was design an isolator that can move back and forth in two directions and, thus, doesn’t have to overcome the force of the brake spring which is much better for long-term reliability. Amazing, right?

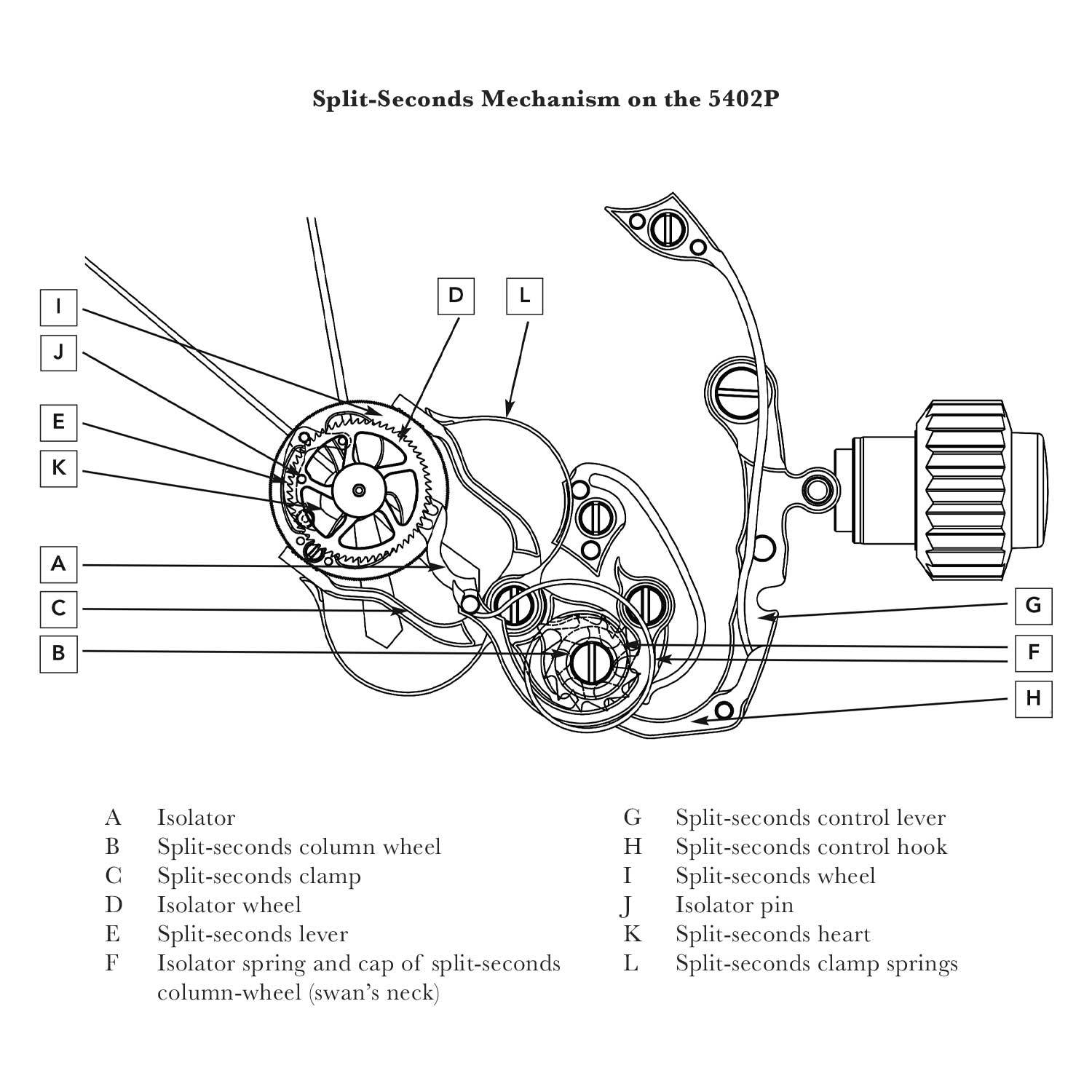

Parts of the split-seconds mechanism on the 5402's CH 29-535 PS Q

The unique Patek Philippe design is based on an isolator (A) controlled by the split-seconds column wheel (B). As soon as the split-seconds clamp (C) closes, the beak (P) of the isolator falls between two columns and with its teeth advances isolator wheel (D) that uncouples split-seconds lever. When the splitseconds clamp is opened again, the beak (P) of the isolator is lifted onto a column; its teeth turn the isolator wheel in the opposite direction and the split-seconds lever is released again. The swan’s neck cap of the column wheel doubles as a spring (F) that constantly presses the isolator (A) against the split-seconds column wheel.

The split-second version of the CH 29-535, the CH 29-535 PS Q found in the 5204

This new 5204 was a completely different animal. First, at 40.6mm, it was significantly larger than its 36mm predecessor. Second, the style of its case was significantly sportier. While it had straight lugs as opposed to the flared, faceted lugs of the 5270, the 5204’s lugs featured a pronounced step to them. As opposed to the steeply raked bezel of the 5270, the 5204 has the more classic, concave-style bezel that gives its case a cleaner and more refined look than its unabashedly aggressive sibling. Added to this are the 5204’s magnificent domed pushers, reminiscent of those from the 1563. Finally, a pusher for the split function was integrated into the crown in the same style as the 5004 to keep the overall appearance of the watch clean. This restraint was echoed, in particular, by the choice of baton indexes for the watch. But wait, because, all of a sudden, you realize that the indexes and the dauphine-style hands are luminous.

The Patek Philippe Split Second Perpetual Calendar Chronograph was lauched with the 5204P-001 in 2012; the watch was the first to be powered by the CH 29-535 PS Q

At 40.6mm, the 5204 is significantly larger than its 36mm predecessor, the 5004; the style of its case is significantly sportier

The lugs on the 5204 are straight with a a pronounced step; the bezel on the case is a more classic, concave-style bezel that gives it cleaner and more refined look

The Patek Philippe Split Second Perpetual Calendar Chronograph Ref. 5204P-011 in platinum with the black dial, launched in 2014 (Image: Sothebys.com)

Here’s a stunning black-dial version in yellow gold with luminous hands, also made for Mike Ovitz.

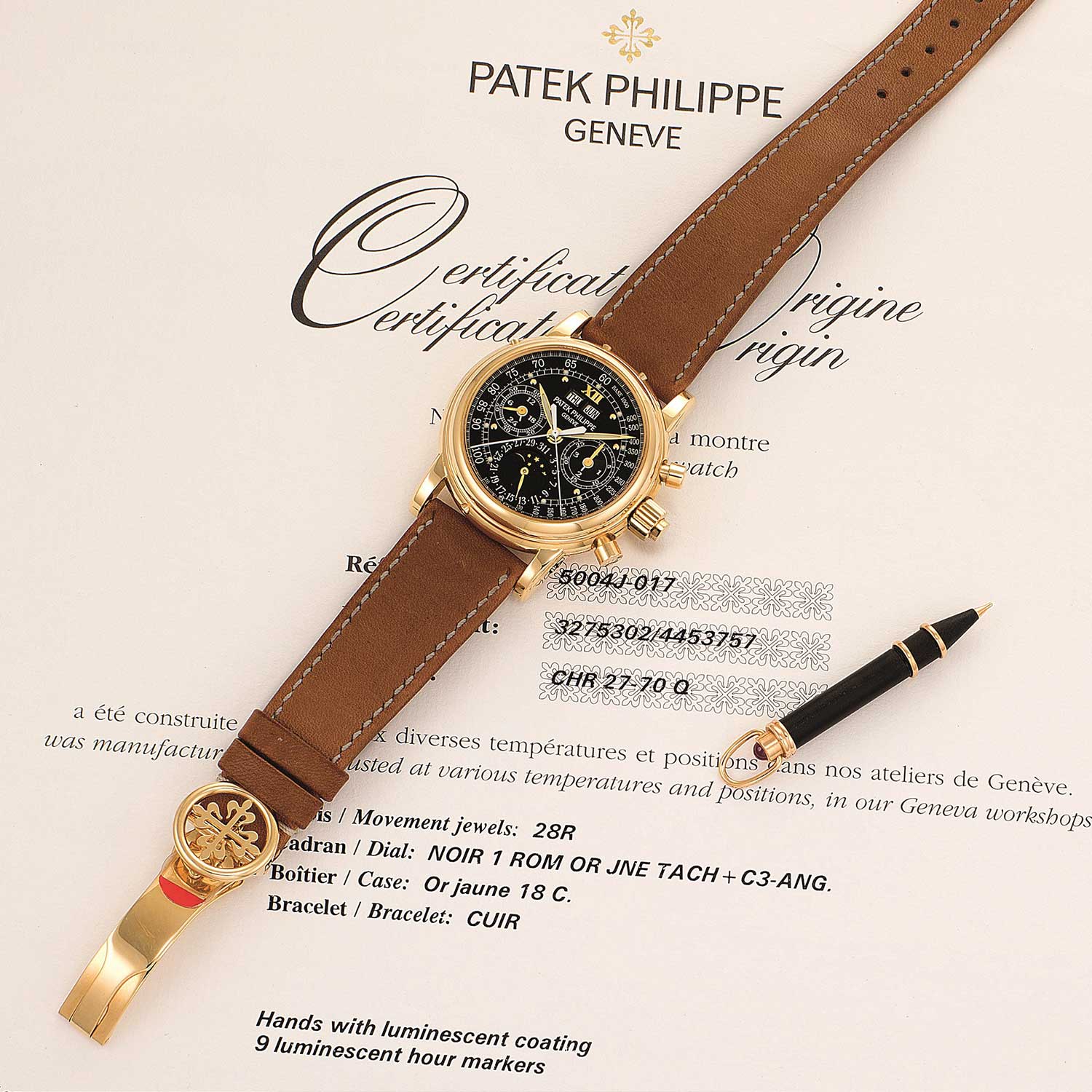

Patek Philippe Ref. 5004J-017; possibly unique yellow gold perpetual calendar split seconds chronograph wristwatch with moon phases, leap year, special luminous monogram dial; reportedly the former property of Hollywood mogul, Mike Ovitz (Image: phillips.com)

Closer look at the dial of the Patek Philippe Ref. 5004J-017 (Image: phillips.com)

Certificate of Authenticity directly from Patek Philippe on the 5004J-017 (Image: phillips.com)

The rose white dial version of the 5204, the 5204R-001 was launched in 2016 and remains in production to this day

The 5204/1R-001 with the brick style rose gold bracelet on the rose gold, black dial version of the 5204 was launched in 2016 and remains in production to this day

The Ref. 5370 Split-Seconds Chronograph

The Patek Philippe 5370 split-seconds chronograph is an absolute killer. Why? To me it’s the combination of aesthetics and technical innovation. From the aesthetics side, it reminds me of my two favorite Patek Philippe split-second chronographs: the 1436, which is the split-seconds version of the hallowed reference 130 and the insanely beautiful 1563, which is the split-seconds version of the transcendent 1463. Incidentally, a version of the 1563 owned by the jazz great Duke Ellington featuring stunning Arabic numerals resides at the Patek Philippe Museum. Here is a picture of it below.

1946 Patek Philippe ref. 1436 yellow gold split second chronograph with Breguet numerals (Image: Sothebys.com)

The Auction House Phillips De Pury & Luxembourg Auctioned Off A Rare Patek Philippe 1563 Wristwatch That Once Belonged To Musician Duke Ellington For $1,593,396 May 13, 2002 At The Hotel De Brgues In Geneva, Switzerland. Ellington Purchased The Watch In Geneva In 1948. (Photo By Getty Images)

The immensely revered, Patek Philippe 5370P-001 Split-Second Chronograph with a black enamel dial and gold applied Breguet numerals; the watch was launched in 2015 (©Revolution)

Finally, the leaf-shaped hands are luminous — something that many people overlook because it is so subtly executed. But I can tell you for a fact that any luminous hand, Breguet-numeral Patek Philippe chronograph comprises the Holy Grail of collectability; add to this the split-seconds function and this is, without a doubt, the most sought-after triumvirate of Patek Philippe features in the world.

From the perspective of the square pushers, the 5370 is more in alignment with the 1436 (©Revolution)

From the viewpoint of the case, its robustness and especially its size at 41mm in diameter borrows spiritually from the 1563 (©Revolution)

Second, in the CH 27-70 you had a spring integrated into the isolator wheel to get it to return to its original position (this is the aforementioned isolator wheel spring) when released. In the new movement, a long, incredibly designed and engineered spring that is integrated into the cap of the split-seconds column wheel does this with far less force, also helping with long-term reliability. Finally, the CH 29’s frequency of 28,800vph also allows it greater stability. So much so that I have always suspected that the CH 29-535 PS in split-seconds form would actually work fine even without the isolator. The only other isolator from this era is found on the Frédéric Piguet 1186 from 1989, which is a rattrapante version of the automatic vertical-clutch chronograph caliber 1185.

Note that throughout the lifespan of the CH 27-70, there was never a split-seconds chronograph-only version of this watch. There were, of course, references such as the 5959, but that watch was based on an ancient Victorin Piguet ébauche.

CH 29-535 PS based 5370 is unique in that it is the only modern split-seconds chronograph designed from the ground up with this feature, with a fully contemporary movement and a focus on perfect performance (©Revolution)

The 5370P-001 was discontinued in 2020, along with the introduction of the 5370P-011. same gorgeous feat of watchmaking, now with a blue grand feu enamel dial (©Revolution)

The Patek Philippe Ref. 5370P-011 Split Seconds Chronograph was launched in 2020 (©Revolution)

Case profile of the 5370P-011 showcasing some masterful artistry on the lugs of the platinum case and square pushers ala Ref. 1436 (©Revolution)

It is Patek Philippe's convention to identify their platinum cases by placing a small diamond on the side of the case, just under the 6 o'clock hour marker; seen here on the case of the 5370P-011 (©Revolution)

The caseback view of the 5370P-011, showcasing the CH 29-535 PS within (©Revolution)

The Ref. 7150 Ladies’ Manual-wind Chronograph

In 2018, Patek Philippe simultaneously delighted and frustrated watch collectors around the world with the 7150. The delight stemmed from the fact they had created one of the most astonishing beautiful chronographs in their collection. The 7150 was a veritable litany of Patek’s most revered designed codes from their history with the chronograph. The 38mm case featured the “spider” lugs of the beloved reference 1579 from 1943. This 36mm vintage watch represented one of the most significant acts of modern design in Patek’s history and examples of this watch regularly achieve high auction results, with platinum versions trading for over two million US dollars.

Patek Philippe ref. 1579 gold and steel chronograph with Arabic numerals fitted on a Gay Frères “grains of rice” bracelet adored on the gold spider lugs of the timepiece (Image: John Goldberger)

The Patek Philippe Ref. 7150-250R-001 was launched in 2018, featuring a silvery opaline dial, framed by a bezel encircled with diamonds, applied Breguet numerals, Breguet hands, a pulsation scale, mushroom-shaped “Tasti Tondi” pushers, and "Spider" lugs from the 1579

Note that the crown of the 7150 is also similar to the flat, oversized winding crown of the 1463. Then, just to make us more delirious, the dial of the 7150 featured applied rose-gold Breguet numerals. Breguet numerals are found on the most desirable versions of the references 130 and the 1463 as well as the references 1436 and 1563 split-seconds chronographs made from the 1930s to the ’60s. Today, Breguet numerals are reserved for the most complicated and desirable models, such as the magnificent platinum-case split-seconds chronograph 5370, featuring a blue grand feu enamel dial with applied white-gold Breguet numerals.

Then, just to tease us further, the 7150 features Breguet-style hands, presumably to match the Breguet numerals; however, it should be noted that this style of hands is actually quite unusual for a Patek Philippe chronograph. A lovely final touch is the use of a pulsation scale used by doctors in the past to calculate the heart rate of patients based on 30 beats.

A closer look at the dial of the Ref. 7150-250R-001 with the pulsation scale, applied Breguet numerals and Breguet hands

The bezel of the Ref. 7150-250R-001 is adorned with 72 diamonds

A closer look at the Breguet hour hand of the Ref. 7150-250R-001

Mushroom-shaped “Tasti Tondi” pushers on the Ref. 7150-250R-001

The Patek Philippe Ref. 7150-250R-001's lugs are inspired by the "Spider" lugs from the ref. 1579

The 2018 Patek Philippe Ref. 7150-250R-001 is powered by the manual winding Caliber CH 29‑535 PS

So I’m sure you are at this point saying, “These are all amazing qualities,” and rushing down to the nearest Patek authorized dealer. But not so fast. Because, as I said, this 7150 has also frustrated a great many male collectors; with its gem-set bezel, this timepiece was intended to be a women’s watch. Now, bear in mind that should you love everything about the 7150 and are not deterred by its diamond-set bezel, then by all means strap one on. I’ve been sorely tempted to myself.

Add to this amazing masterwork of design the fact that the watch features the magnificent CH 29-535 PS and I cannot think of a greater medium-sized, gem-set manual-wind chronograph. Time and again, I’ve heard the most savvy male collectors bemoan their fate, “If only they made the 7150 without the diamond bezel,” pause as their eyes get a faraway look and they whisper, “Or could you imagine it in steel.” Whether this will happen, only time will tell. Sadly, it probably won’t.

The Ref. 5172 Manual-Wind Chronograph

What I love about the reference 5172 chronograph introduced to us in 2019 is that it is an act of full design maturity, coming from a man ascending to the peak of his design powers. And that man is, of course, Thierry Stern. The 5172 is one of my favorite watches in Patek’s contemporary collection because, in ethos, it harks back to the era of the reference 1463 in that it is a large-sized sporty, water-resistant chronograph that tantalizingly mixes the concepts of elegance and adventure together. At 41mm in diameter and 11.45mm in height, it has considerable wrist presence. With its white-gold case, navy-blue dial with luminous hands and indexes, it is thoroughly rooted in the modern world. And yet, at the same time, it is a fantastic repository of classic Patek Philippe references that reach back almost a century.

To begin with, its design is based on the gorgeous Patek reference 5320 perpetual calendar — a watch that is, in turn, inspired by the legendary water-resistant steel perpetual calendar reference 1591 made in 1944 and delivered to a maharaja in India. This discerning gentleman clearly wanted a masterpiece of complicated watchmaking from the maison that introduced this concept, but he also wanted a watch he could swim or even play sports with; a timepiece thoroughly without compromise. And that has been perfectly transmitted through the cream-dial 5320, which takes its indexes and syringe-shaped hands from the 1591, and the same design code is now also perfectly imparted to the 5172.

The Patek Philippe Ref. 5172G-001 was launched in 2019 with a blue dial featuring luminous Arabic numerals, hour and minute hands, and a tachymeter scale

Made by Patek Philippe, a steel pièce unique ref. 1591 water-resistant perpetual calendar with luminous Arabic numerals and hands made for an Indian maharaja in the 1940s (©Revolution)

The Ref. 5172G-001 is adorned with luminous Arabic numerals, hour and minute hands

Mushroom-shaped “Tasti Tondi” pushers on the Ref. 5172G-001

The triple-stepped lugs of the Ref. 5172G-001

So that’s it. Here endeth the story on Patek Philippe’s modern chronographs, and I hope you enjoyed perusing this text as much as I enjoyed writing it. I am aware that we have not explored Patek’s automatic chronographs featuring the caliber CH 29-535 PS yet. But that, hopefully, gives us something to look forward to.