Alpina and the Era of the Adventure Watch

News

Alpina and the Era of the Adventure Watch

“Ice climbing!? Like, climbing up a frozen waterfall? That sounds insane.”

I was about 10 years old at the time, having just learned that a close friend of the family, spent his winters bolting himself to fragile ice walls suspended a couple hundred feet in the air. It was a mind blowing idea and I vowed right then and there I would never do anything that crazy…

The memory flashed through my mind as I stood beneath the craggy, frozen, waterfall which stretched up about 70 feet above my head. We had been hiking for the better part of the past hour up a steep wooded incline, the trail (if one could be so generous as to call it that) was made of switchbacks obscured by knee deep snow. The sun had just begun to peak over the mountain ridges of Yoho National Park in British Columbia, Canada, bringing with it a miserly touch of warmth, raising the temperature to a balmy -6 degrees Fahrenheit.

I took off my pack which was weighed down by my camera, helmet, an additional puffy coat, and two ice axes. I glanced down at my wrist, my Alpina Seastrong Diver Extreme Automatic GMT indicating that we’d made decent time – about 40 minutes since we’d left the cars down an unmarked (and snowy) access road and begun our mini-trek up to the wall.

But that was the easy part. What would come next would push all of us to our absolute breaking points and, before the day was done, at least several of us would be in real danger.

Alpina’s History and the Heights of Today

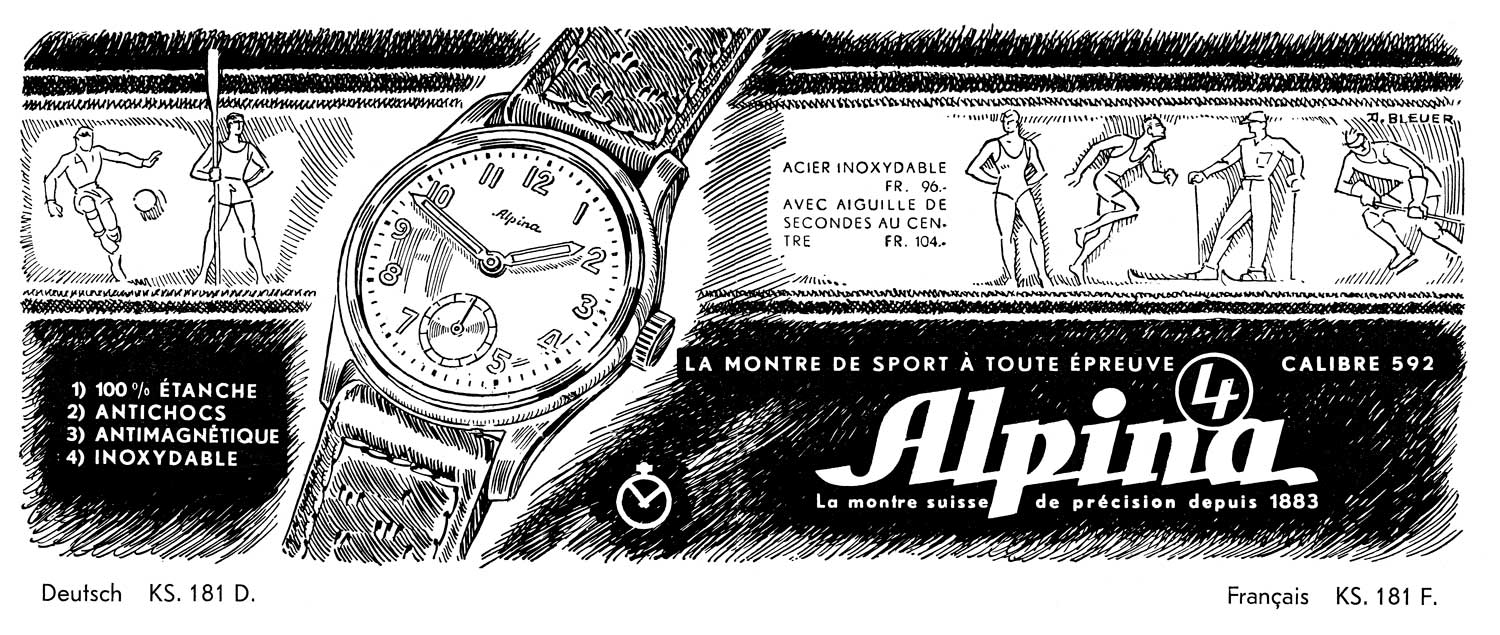

Alpina traces its roots all the way back to 1883, in an era of Swiss watchmaking where the concept of a singular brand identity as we know it today had yet to be formalized. By 1908, both the brand name and the now synonymous red, Matterhorn inspired triangular logo had been officially registered.

Much like the endeavors undertaken by the alpinists for whom their watches were intended, the following century would be comprised of peaks and valleys. In 1938 the Alpina 4 was released, so named for what was defined at the time as the four critical features of a sport watch – an antimagnetic case, water-resistance, anti-shock movement, all contained within a stainless steel case. These features projected the broad expectations of what a watch could endure, the environments and adventures that it would withstand, and the mountains it would conquer.

Today, those metrics have changed, but the intentions have remained. While the Alpiner 4 still exists in modern iterations, alongside other watches like the Startimer Pilot Automatics, arguably the most defining watches of Alpina’s current era are those that feature the ‘Extreme’ cases – the Alpiner Extreme series, and the Seastrong Diver Extreme Automatic and Seastrong Diver Extreme Automatic GMT.

The Extreme case design is a stepped, multipiece case, with contrasting finishes of brushing and high polish. The combination of circular bezels juxtaposed with hard angles and jutting features such as the lugs and the crown guards, results in an aggressive, evocative presence on the wrist – it just feels like these watches want to go somewhere difficult and mix it up.

With relatively thin cases (the Alpiner Extremes coming in at a reasonable 11.5mm thick) and oversized crowns with rubber texturized grip, these watches are very wearable despite their robustness – fitting comfortably underneath layered jackets, or even large ski gloves with bulky liners. The watches are available on either a texturized rubber strap with a locking folding clasp or on a brushed, flat-link stainless steel bracelet (depending upon the model and variation).

But It’s not enough to merely make a cool looking watch and claim its capacity for endurance. It’s another thing entirely to put those watches in the hands of, or rather, on the wrists of, some of the most extreme athletes in the world. Thus in 2018, Alpina put their money where their mouth was by sponsoring the Free Ride World Tour, the most extreme downhill skiing and snowboarding competition in the world.

Each year, a roving band of maniacal skiers and snowboarders travel around the globe to 6 of the most challenging and intense environments, descending mountain faces which, by the furthest stretch of the definition, can be called slopes. What they are in reality is a series of wildly steep snow-covered cliff bands and gullies. The aim is for competitors to descend these runs with a combination of control, style, and flair.

Alpina not only sponsors this competition, but counts several of its most notable competitors as ambassadors, including Maxx Palm, Juliette Willmann, Sybille Blanjean, and Victor de Le Rue. Every time these riders drop in for a run, they put their bodies, and sometimes their lives, on the line. It is an understatement to say that the demands they put on themselves and their equipment is intense. If their kit isn’t built to the highest standards, it doesn’t survive. Simply put – they eat gear for breakfast.

Dropping Into The Extreme

It had been almost exactly one year since I had found myself sitting inside the small well of a sapling tree, my skis stuck into the steep slope to my back in an ‘X’ shape, my lens pointed at the opposite side of the massive bowl that descended from Terminator Peak to photograph the competition. As challenging as last year’s comp had been to shoot, this year was even more difficult.

The temperatures were significantly colder, posing risks to both limbs and photography equipment. The competition was being held on the opposite side of Kicking Horse Mountain in British Columbia, Canada. Competitors would be coming down a sheer face known as Ozone, which sits at 8,218 feet, and I’d be photographing from the opposite ridgeline, along a sketchy catwalk called Redemption Ridge. I later learned it was dubbed ‘Highway to Hell’ by the locals – not exactly comforting.

While I grew up skiing and am generally capable of handling black and even double black diamonds, the exposure always gets to me, conjuring up all sorts of improbable fears and anxieties. This morning was no exception, as I made my way along the skied out path towards the lower section of the ridge. I tried to remind myself that, the 1,000 ft face just a few feet to my left notwithstanding, I was not about to fall off the world. I reached what I thought would be a decent vantage point and set up to begin shooting.

Riders were absolutely sending it down the cliff bands on the opposite side of the bowl. Despite bringing what I thought was a massive, 200-800mm lens, I was still too far away to really capture the action in the way I had envisioned, which meant one thing – I was going to need to ski down the face of the bowl to shoot from the finishing line. I signaled to my friend and fellow photographer Ed Rhee, who was also covering the competition, that we needed to head down. We both clipped back into our bindings and made for the edge to drop in.

Due to the early hour of the competition and schedule, we hadn’t had time to do any real warm up runs. My legs felt as shaky as a new born deer as I made my way to the edge. I’d picked a path that was fairly simple – a steep drop in, one jump turn around a fairly pronounced mogul, and I’d be home free to begin the long traverse over to the finish line, skirting just below the cliff band.

In that moment, I looked down at my watch, the Alpiner Extreme Free Ride World Tour Edition, the same one I’d been wearing the last time I found myself on this objectively terrifying mountain. “Right. Do it before you lose your nerve,” I said to myself. Tunnel vision set in, and I dropped down into the bowl, the sound of my skis scraping along the hard packed snow, leaving Ed still getting ready up above (sorry again, Ed.) I took a deep breath, planted my pole, and sprung around it, twisting my hips and counting on muscle memory to ensure the edges of my skis caught me as they cut into the slope, thus preventing me from tumbling several hundred feet to the bottom.

I won’t claim it was the most graceful jump turn of my life, but it worked. I swallowed hard, looked up at the steep ridge above me and began my long traverse down to the finish line. I stayed there for the following 4 hours or so, shooting as much as I could and trying to keep my feet from freezing. I watched as rider after rider sent incredible, death-defying lines down this massive face, the announcers losing their minds as the crowd cheered with endless exuberance.

Drained by the extreme cold, the batteries for my camera were all tapped out, and the memory cards were malfunctioning (always shoot with a backup SD card!) The batteries in my heated gloves and socks had been dead for at least an hour or two. It was time to head down. The only way was a long twisting black diamond run that stretched almost to the very bottom of the mountain. By the time I reached the base, I was absolutely smoked and so was my equipment – my watch, on the other hand, continued to tick away as though it was a day at the beach.

Against the Frozen Wall

Later on, we arrived in the evening to the Emerald Lake Lodge – a pristine retreat along the frozen shores of a stunning lake of the same name. Replete with mountain charm, minimal Wi-Fi connectivity, and no cell reception, I felt like I was a thousand miles away from anyone else in the world. The moon and stars shone their icy light across the frozen surface of the lake. Stepping out into the air to walk to our rustic but pleasant cabins, I could feel my breath freezing in my beard as I exhaled. It was -18 degrees F.

The following morning at 6:00 am we were up and ready to move, with easily the most difficult, and most dangerous, excursion of the trip awaiting our arrival. We would be spending the morning ice climbing on a small but intimidating crag known locally as Waterworks. As someone who has an abject fear of heights and exposure (even the Gondola on Kicking Horse Mountain gave me the yips) I was excited but supremely apprehensive.

Driving along the road from the Emerald Lake Lodge to our meeting point, the mountains flanked the highway with statuesque grandeur, with steep, white couloirs splitting their rocky faces. Wisps of hazy clouds danced across the peaks, illustrating the frigid, subzero temperatures we would soon be enduring. The truth of the matter was, none of us were truly prepared. How can you be unless you’ve spent time in such conditions? There’s cold and then there’s cold – this was most certainly the latter.

Decked out in new gear provided generously by Arc’teryx, I was feeling naively ready for the day. I had doubled up on base layers, had recharged my heated gloves, and donned the Alpina Seastrong Diver Extreme Automatic GMT – arguably the most complete travel and adventure watch in the current lineup. The combination of 300m depth rating, slightly smaller case size of 39mm, GMT timing function, and a 50 hour power reserve, means there’s very few environments or excursions this watch would not be well suited for.

We pulled into a parking lot and after a short but sobering safety briefing from our guides (and signing several chilling personal liability waivers) we set about putting on the provided Scarpa climbing boots and packing crampons, ropes, helmets, and ice axes into our packs. Unfortunately, due to some sizing issues, most of us had to remove at least one layer of socks in order to fit into the boots. But on we went regardless, determined to meet the challenges of the day.

Even through facemasks and gators, the air was sharp and icy as we breathed heavily trudging up the snowy path. Before long, two of our group had to turn back, the combination of knee deep snow, the cold, and the fact that we were still a solid half an hour from reaching the wall proving too much. The rest of us pressed on.

We reached the top and stared in awe at the towering wall of blue ice that rose before us. It was stunning, but there wasn’t time to stand around and admire. Immediately the guides went to work rigging up top ropes and handing out additional down layers – belay pants and jackets – that we may hope to stay somewhat warm. Despite the insulation, our feet were already beginning to throb in the cold, early signs of frostbite beginning to emerge.

I had known what I was getting myself into coming into this excursion to a degree – it was dangerously cold, in one of the most extreme winter environments I’d ever been to. But despite my expectations, the reality of the negative temperatures and the intensity of the short but arduous hike smacked me square in the face. I immediately put my pack down and sat on it, ensuring that I did not lose more body heat to the frozen ground. I removed my boots and started to work the blood back into my fingers and toes – an essential safety precaution I would repeat a few times before the day was done.

After a quick tutorial, we took turns belaying or climbing, cheering each other on as our two guides gave as effective instruction as they could to a group of desperately inexperienced climbers. Before long, it was my turn to scale the ice. I felt a swell of fear and anxiety well up in my chest and throat, just like on the ridge at Kicking Horse Mountain.

Fumbling a bit with the ice axes to get a firm placement (which is way harder than it looks) I slowly started making my way up the initial pitch of frozen ice, carefully ensuring that with each sharp kick, the blades of my crampons stuck firmly and evenly into the wall. Using the weight of the axe head, I swung with purpose into the frozen wall, the violence of force reverberating into my hand and arm. With each subsequent kick and swing of the axe, I tried my best to recall all of the pointers I’d seen while binge watching world renowned Ice Climber Will Gadd’s tutorial videos in preparation for today, all while desperately avoiding looking down.

As I continued, it began to click. Leveling my feet felt more intuitive, my axe strikes more solid. Somehow, before I even realized, I had made it up the first pitch to a small frozen landing, about 50 feet or so above where I’d started. I turned around, supremely pleased (and a little shocked) with what I’d just done.

A second pitch continued above me for another 20 or 30 feet. But hey, I’d already done it, I pushed through the fear. Good enough, right? “I think I’m good to come down!” I shouted to the guide belaying me. “F*** that! Finish it.” He barked back. I took a deep breath – “Good point, I guess,” resuming the climb and making my way up the second pitch.

Finally reaching the top, I stopped to admire the view, in genuine disbelief of what I’d just accomplished. I called down that I was ready to begin the descent. But there was a problem. The rope had either snagged itself or frozen in place. My belayer had heaps of slack, but my end of the rope was taught and wouldn’t budge.

“You have to get the rope loose. Bounce on it to free it!” my guide hollered up to me. “Bounce on it!? Jesus Christ!” I thought, feeling the wave of panic setting in, my eyes welling with tears, my brain shutting down. “Oh god… Oh g… No! Knock it off!” I shouted to myself, “I got up here without freaking out, god dammit, and I can get back down.” I tugged with determination at the rope over and over again, but to no avail. I had to put my full weight on it – as close to a leap of faith as I’ve ever taken. Pulling my body weight backwards with force, it took four or five strong jolts to free the rope from whatever infernal bind had held it in place.

After a few more minutes and a series of carefully placed steps, I was back down. I looked up at the tower of frozen water and rock above me. What a few minutes ago had been a wall of apprehension and fear was now a glistening monolith of achievement.

We each finished our respective routes, jubilant that all of us had made it up to the top. We all put our hands into a circle for the obligatory group wrist shot, our watches peeking out from beneath coats and gloves, now all containing the memory and the meaning of what we had just accomplished while wearing them. But despite our personal success, it was the cold that had truly won out.

As we made our way down, it became clear that frostbite had set in on several of my companion’s feet. Blisters having formed, the pain would have been excruciating had it not been for the numbness (though that would woefully come later). We were fortunate to have turned back when we did, for as we later learned, they were mere minutes away from potentially losing toes to the icy air.

The Era of the Adventure Watch

In today’s digital era watches have, for many, become technologically unnecessary. We have phones, computers, personal locator beacons, GPS, all built upon an infrastructure of technology at our disposal. Perhaps we have left that time behind where our watches were the only tool for the job. But despite that, we still wear our watches. We still love our watches. We still use our watches.

Indeed most people don’t need tool watches anymore and even fewer who own them actually use them for the rugged purposes for which they are intended. Despite that, watches still have the power to captivate, inspiring us with dreams of exploration and adventure, of lives not yet lived. They have become evocative objects that sit on our wrists and beckon us to rise to the occasion of our ambitions.

We set out to test Alpina’s watches but also to test ourselves, undertaking challenges that were far outside our comfort zones if only for the sake of seeing what we are capable of. In doing so, we not only learned what our own limits were, but were reminded that a truly great watch is still an important piece of equipment even today. Batteries drain in the cold, screens break, connectivity drops, technology fails. But despite our excursions – skiing on one of the most insane mountains in North America, numerous outings into the frozen wilds onto lakes and glaciers, and enduring a sub-zero day on an ice wall, all of our watches continued to work in perfect order.

It’s easy for a company to make claims about where their watches are meant to be used. For many, it’s a lot of talk. But the truth of it is our Alpina watches out performed us all. By the end of the trip, we were absolutely wrecked; a haggard group of exhausted, sick, limping watch journalists who wanted a taste of the real thing – and got it. The watches, by contrast, were fine, barely showing a scratch. Alpina’s timepieces are built the way they are for a reason – to withstand the extreme environments of the world and accompanying those intrepid enough to explore them. It was true of Alpina’s watches at the turn of the 20th century and it remains true to this day.

Alpina