In the ascendance of independent watchmaking, these three individuals are primus inter pares.

In the past half-decade, there’s been a tremendous surge of interest in independent watchmaking. The once-niche sector of the industry that brings to mind the silhouettes of lone watchmakers toiling at their craft in small ateliers nestled in the heart of Switzerland, has now emerged at the forefront of horology, capturing the hearts and minds of both the seasoned collectors and the wide-eyed newcomers as the ultimate expression of horological prowess.

In many ways, the very nature of independent watchmaking defies the trajectory of the watch industry at large, which has been a narrative shaped by the twin forces of industrialization and democratization. Most independent watchmakers embark on the pursuit of horology as an art form, be it artisanal, conceptual, technical or artistic, without consideration for expense or time, and it is this that separates them from the bigger watch brands and conglomerates. In developing a much more specialized line of inquiry where innate purpose holds the lead over commercial expectations, their influence on the industry is often directly inverse to their production output.

Revolution has sought to recognize these watchmakers who work from an inner necessity to expand the boundaries of horology. They range from the great and established independents who have become the cynosure of all of horology today, to the latter-day stars who have made distinct developments in their chosen fields, to the up-and-coming watchmakers who have shown great promise in their debut work. Yet among all of these watchmakers who demonstrate a high level of excellence in their craft, if I had to pick just three whom I think are the legitimate rulers of independent watchmaking today, it would be the following individuals.

Rexhep Rexhepi: The Messiah

Rexhep Rexhepi

One of my favorite movie scenes occurs in Mike Nicol’s seminal The Graduate (1967), and it happens when at his graduation party Ben Braddock is pulled aside by his family friend Mr. McGuire, who stares at him with evangelical fervor and says, “I have just one word for you. Are you listening?” He then pauses and utters with a sense of revelatory awe, “plastics.” In my mind, I can visualize this: In any given night, in any given teeming tier-one metropolis, a seasoned collector at a watch event will whisper to a neophyte the following words, “I have just one name for you.” At this point, ears will prick up around the room. “Rexhep Rexhepi.” Wait, who you ask? Well, if you’ve just awakened from a Rip Van Winkle-like slumber or been in Transcendental Meditation since the onset of the COVID pandemic, you would be excused for your blasphemic ignorance. Otherwise, like all other watchmaking devotees, you will instantly recognize this Albanian name as belonging to horology’s new Messiah.

Rexhepi is an absolute aesthetic and technical genius. More than that, his watches resonate with that most rare of qualities, “soul.” His ticking creations made in his atelier on Grand-Rue in Geneva’s Old Town feel like they possess an energy, a vitality that ancient philosophers referred to as life force. There is something about Rexhepi’s watches, their visual harmony, the uniqueness of their design, the almost eerie perfection of their finishing, that causes them to feel irrefutably alive. When I asked who his favorite young watchmaker was a few years ago, the man universally acknowledged to be the heavyweight chap of independent watchmaking, François-Paul Journe, told me, “Rexhep.” He then added with a chuckle, “Especially now that he’s stopped copying me.” I took this to mean that he was proud of Rexhepi, who had set out on his own after working for François-Paul, and has defined his own all-original, totally singular and perfectly articulated horological voice.

Like that of every great hero, Rexhepi’s initial journey in life was characterized by hardship, a theme that would revisit him at the onset of his career. Rexhepi was born of Albanian descent in Kosovo at a time of ethnic conflict with the Serbians that populated his land. His grandmother tried to shield him from this. He recalls, “She would try to make it a bit into a game. At 12 years old, we didn’t know the real extent of the violence.” But at 14, his grandmother, fearing the genocide perpetuated by the Kosovo Liberation Army, sent him and his brother to Switzerland to live with their father. Shortly after arriving, Rexhepi found himself enrolled in the Patek Philippe watchmaking school. He explains, “My father had been living in Switzerland for many years. When he came to visit once, he showed us a Patek Philippe. I always had this watch and this name in my mind. When I came to Switzerland, I knew I was in the land of watches and I wanted to work at Patek. Early on, I felt alienated. I didn’t have many friends, but I discovered watchmaking and I found my passion. I knew I wanted to follow this path. It wasn’t easy; my first interview at watchmaking school was a disaster; they gave me something to file and I made a mess. So, I practiced my filing on my own and when I went for the selection exam for Patek Philippe, I was ready.” It was while at school that Rexhepi had his moment of epiphany. He declares, “I held a Patek 10-Day Tourbillon in my hand and I was blown away. I said to myself, one day I want to create a watch this beautiful on my own.”

His very first watch, the Akrivia AK-01 Tourbillon Chronographe Monopoussoir; (Below) the AK-06 with exposed dial-side mechanics which includes a power reserve mechanism, a zero-reset seconds and keyless works

From Patek, Rexhepi transitioned to BNB Concept, a high complications specialist founded by three ex-Patek hotshots, Mathias Buttet, Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini. Rexhepi instantly fell in love with movement development at BNB. He says, “It was liberating that I could work on the grand complications I dreamed of. I helped develop the movement that became their tourbillon chronograph. It was the first chronograph where you could see from the front of the watch. This gave me a little taste of what was possible.” From BNB, Rexhepi then found his way to the atelier of the man who would become his hero and mentor, François-Paul Journe. It was while working with Journe that Rexhepi began to envision his path as an independent watchmaker. He explains, “Journe does something totally different. I like that. It is a vision totally unique to him. Journe thinks about his legacy. He has so much admiration and love for the history of watchmaking and his motivation is to establish his chapter in this story.”

Inspired by his mentor, while still in his late 20s, Rexhepi decided to strike out alone with the vision of a very specific cushion-shaped, avant-gardist watch. He called his brand Akrivia, which is the Greek term for “precision.” He states, “When I first started, of course, I thought of putting my name on the dial. But I also had doubts. Why would anyone want a watch with a funny Albanian name on it? I thought I must be humble…” Instead, he poured all his desire to express beauty into his first watch, the AK-01. Its movement was the very same BNB tourbillon chronograph movement he had worked on years before but transformed with an absolutely ravishing rearticulation of bridges and finishing at a Philippe Dufour level. Rexhepi says, “Pierre Favre [of MHC, a high-end movement designer and manufacturer] gave me the possibility to use this movement. I put everything I had into this watch, especially the finishing. Wei, what you may remember is that at the time very few people were interested in decoration. They would say, ‘Stop with this, this is too old fashioned.’”

The RRCC I and AK-01 are the first of two distinct lines; the Rexhep Rexhepi collection focuses on more classical watchmaking while the Akrivia range is characterised by unusual designs and complications.

After he had finished the watch, Rexhepi stepped back to take in the grandeur of his own creation. He says, “I was sure that everyone will want my watch. But no one bought one for two and a half years.” Thus ensued one of the hardest periods of Rexhepi’s life as he waited for his first client. It’s hard to imagine the existential toll it took on his mind and spirit. But this Albanian refugee never gave up. He says, “I promise you, when you have nothing but time, all you can do is think about how to do better. It was an important experience for me. I learned that life is not easy; there are so many ups and downs. Finally, a guy from Kosovo opened the door and bought one.” Rexhepi toiled on several other Akrivia watches; it was only in 2017 with a smaller timepiece that showed off its phenomenally finished gear work on the front of a hand hammered dial that the momentum shifted in his favor. Says Rexhepi, “I launched the AK-06 in 2017. I wanted to create a watch that could really show the world who I am. I wanted to show symmetry, decoration and feature what I thought was technically interesting with the balance brake and the zero reset seconds hand. I wanted to reveal my vision to the world, so I opened the dial.” The AK-06 inspired a visit by an individual named Michael Tay.

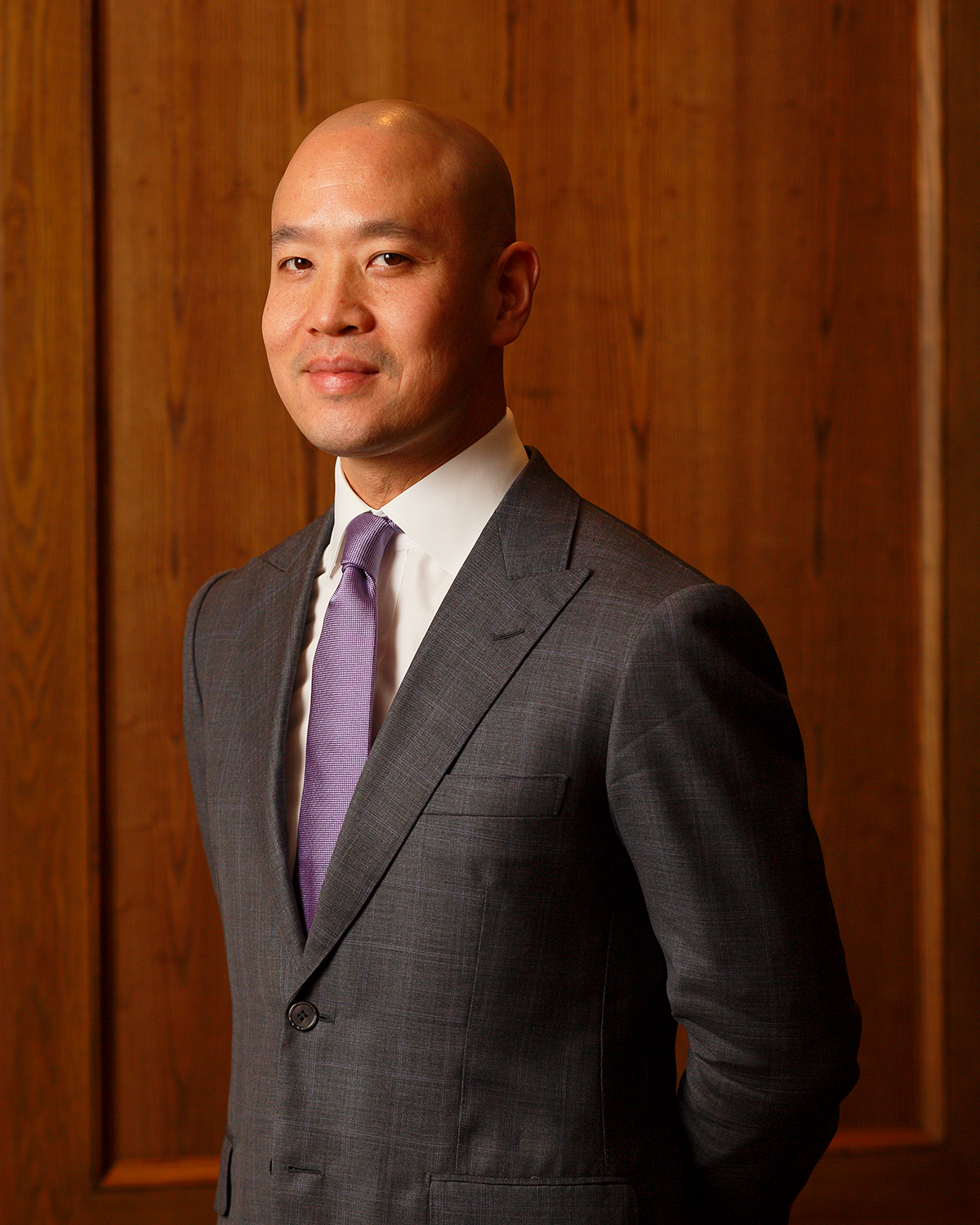

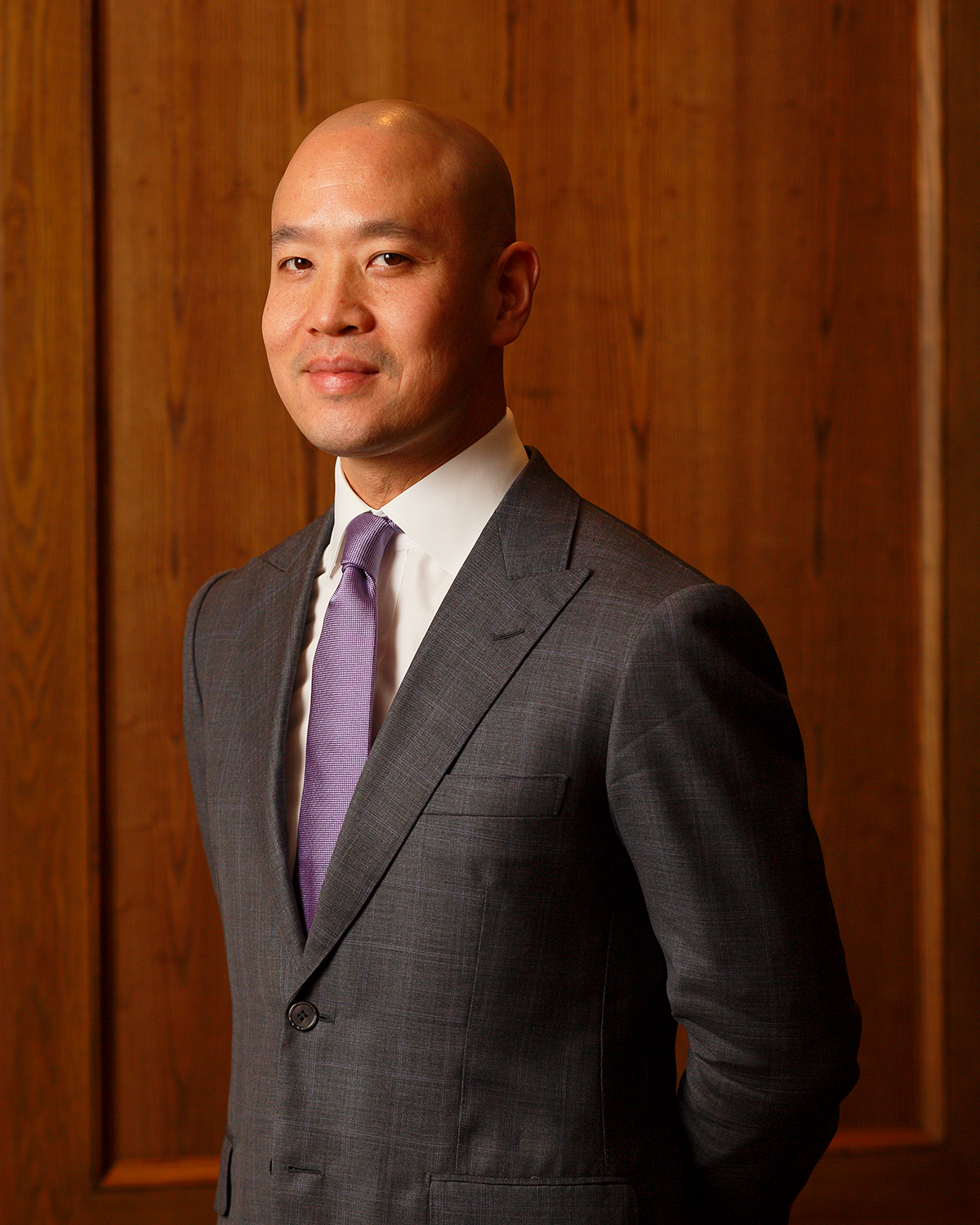

Michael Tay

Tay, whose company, The Hour Glass, had been the first to represent Philippe Dufour, was actively searching for a new Philippe Dufour and found promise in Rexhepi. He proposed something extraordinarily daring, that Rexhepi make a round classic watch and feature his own name on the dial. Rexhepi recalls, “Mike Tay was the guy that really convinced me to create the

RRCCI [Rexhep Rexhepi Chronomètre Contemporain I]. The idea was already there, but I wasn’t sure until he pushed me to believe in myself. I am Albanian, I am from Kosovo, I was really shy about putting my name on the dial of my watch. My father told me, ‘You have to be discreet, you have to be respectful.’ Mike said if you want to do it, believe in yourself and just do it.” The year it was launched, the RRCCI became the 2018 winner of the Men’s Watch category at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève. Says Rexhepi, “That moment was so important to me, because it was a recognition that after all my years of struggle … this industry which I love so much also appreciated my work.” But the impact of the RRCCI would be even greater than Rexhepi realized.

The RRCC II in platinum with a black enamel dial and seconds sub-dial in translucent grey enamel

I’ve referred to Rexhepi as independent watchmaking’s Messiah. It is high praise, but there’s a good reason for this. Spiritualism is not normally a quality associated with luxury objects. Yet their power to stir emotion, to provoke, to uplift, edify and transform, is real. Take, for example, the aforementioned Chronomètre Contemporain created by Rexhep Rexhepi and its capacity to manifest emotion. Going back to the moment when Rexhepi presented this watch in 2018 at the Baselworld watch fair, as he laid it out on the table in front of him, a digital picture was taken. The image was transmitted through the magic of Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol and, a few seconds later, appeared on screens around the world. One such display was situated nearly 6,000 miles away and belonged to one of the art world’s biggest stars, the

L.A.-based artist Wes Lang. His heart started hammering. Desire for the watch slammed into him like a wave off Ehukai Beach on Hawaii’s North Shore.

Wes Lang on the left

Recalling the first time he set eyes on the watch, Lang says, “Every detail of the RRCCI was so profoundly considered and so perfectly executed: the mirror polishing of the concave bezel echoed by the thick bezel on the otherwise graceful lugs; the iconography of the dial, which is at once classic yet refreshingly original; how he [Rexhepi] stylized the hour track which intersects with the seconds subdial, but both of these retain the full resolution of their details. If he had lost a single hour marker or seconds mark at this juncture, the watch would have somehow lost its meaning as a chronometer. But he kept every detail in, and not only that, he even found the perfect placement for the ‘Swiss Made’ signature. This was design genius at its best.”

Lang was so moved by the images he saw, he immediately sent a request to purchase the 60,000-Swiss-franc watch. To his surprise, he was told he’d been allocated the very last platinum piece Rexhepi would make. Even better, Rexhepi, who was a fan of Lang’s, was going to Los Angeles and would bring the watch with him. Just like that, a friendship was born. Says Lang, “Rexhep and [his then-girlfriend-turned-wife] Annabelle showed up looking like a gorgeous couple at my house and we spent almost every day of their trip together. When you come to really love someone who’s created something that moves you so powerfully, it’s very special. Not many watches or people can do that.”

RRCCII

For me, the design genius of the RRCCI is elevated to its god-tier status by its movement. Like the first two transcendent trumpet notes on “So What” from

Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, the very first impression of a movement should give you everything, yet leave you wanting for more. Why is the caliber of Rexhepi’s CCI the most beautiful time-only movement in existence? It has to do with geometric harmony. Look at the back of the watch. What do you see? It doesn’t matter if you understand watches and their movements, or not. Your eye immediately registers the five circles laid out in a beautiful pattern. If I was to make a Venn diagram of these five overlapping circles, you would find them to be a perfect expression of geometric harmony. Note that the overlap of each of these five circles is perfectly symmetrical — meaning that each circle bisects the other perfectly. Further, because Venn diagrams are used to demonstrate logical relationships, our brains unconsciously associate the movement with the concept of logic. But what’s even more amazing is that these five wheels reduce the function of a watch movement to its bare essentials. Michael Tay says, “There is a sense of poetry in this movement that is harmonious and essential.”

The wheel at the top is the barrel where the power comes from; underneath it is the great wheel which drives the third wheel on the bottom left, which in turn drives the fourth wheel or seconds wheel in the bottom middle. This powers the escape wheel sitting on its own tiny bridge, which powers the balance wheel at the bottom right. The fact that the third wheel and balance wheel are very close in size creates a brilliant sense of visual symmetry. Even the placement of the rubies on the watch is perfectly symmetrical. Add to this the elegant execution of the lithe, curvaceous bridges with provocatively acute internal angles and sharp points to demonstrate Rexhepi’s otherworldly, transcendent ability with finishing, and you’ve got a singularity and maturity of voice that is virtually unrivaled in watchmaking.

The RRCCI represented a moment of transcendence for Rexhepi who followed it up with an arguably even more stunning watch with dead seconds indicator named the RRCCII. The beauty of the RRCCII had a great deal to do with the majesty of its case created by one of the world’s famous case makers, Jean-Pierre Hagmann. How did Rexhepi meet Hagmann? He explains, “The real story is that I got out of a nightclub and into a taxi. The driver asked me ‘What do you do?’ I explained I was a watchmaker and he said, ‘I have a friend that makes watch cases. Do you want to meet him?’ That was Jean-Pierre Hagmann… This was crazy because since I was a teenager at Patek, I dreamed about making watches one day with Hagmann cases.” The result was the RRCCII which represents the elevation of the quality of Rexhepi’s case making to become the very best in the industry.

Says Lang, “No one, I mean no one, makes a handmade case like Hagmann. Look at the lugs on the RRCCII; they are sculpture of the highest order.”

The Rexhep Rexhepi Chronomètre Antimagnétique

What about the dead seconds mechanism that uses a separate gear train? Says Rexhepi, “Chronometry is very important. So, with the dead seconds, I didn’t want to affect accuracy. Placing a dead seconds mechanism on the primary train has a parasitical effect on energy. That’s why we have two trains. You have the star wheel co-axial to the escape wheel. You have a flirt that stops it each second, then it is released and the flirt also gives an impulse to the escape wheel, so it is also helping it. The minute wheel is on the side of the deadbeat seconds, so it doesn’t consume any power.”

Akrivia x Louis Vuitton LVRR-01 Chronographe à Sonnerie

2023 proved a seminal year for Rexhepi. He created a stunning

Revolution Award-winning Antimagnétique pièce unique for the Only Watch charity auction. The auction has been postponed, but Rexhepi already has plans to commercialize this model. He also collaborated with Louis Vuitton on the

LVRR-01 Chronographe à Sonnerie, a tourbillon chronograph with a strike in passing function for the elapsed minutes. Says Wes Lang, “The amazing thing about Rexhep is, he only in his 30s but he’s totally dunking on people [with] one amazing timepiece after another. And he’s only getting started. I can’t wait to see what he achieves 10 years from now, 20 years from now. He’s only going to get better.”

LV Akrivia LVRR

Says Rexhepi, “I’m patient. I want to build my career steadily, trying to do better with each watch. I’m young, I have time. My motivation is to leave behind a legacy of real watchmaking accomplishment.”

François-Paul Journe: The GOAT aka Greatest of All Time

François-Paul Journe

It’s one of those inevitable questions. How does Rexhepi stack up against

François-Paul Journe? To me, this is analogous to comparing Mike Tyson with Muhammad Ali. There’s a great moment on the Arsenio Hall Show back in 1989 where Hall brings our Tyson to meet his hero and cheekily asks who would have won a fight between them at their peak. Tyson beautifully states, “Every head must bow, every tongue must profess, this [Ali] is the greatest of all time.” So too in the world of independent watchmaking, there is but one Greatest of All Time and his name is François-Paul Journe. He once said to me, “If someone composes music, then he cannot ignore Mozart. He can’t ignore Beethoven. He can’t ignore the history of music. He continues in the tradition defined by those that came before him. But every once in a while, there will be a rare genius like Stravinsky that arrives and changes everything. But this doesn’t happen often. In watchmaking, we haven’t witnessed the birth of a Stravinsky for 200 years. The last one was Abraham-Louis Breguet.” Yet, despite what Journe said, what is clear to me, and to the most discerning collectors and journalists the world over, is that our era of contemporary horology has been defined by our own Stravinksy — a genius watchmaker, a man of profound brilliance and, though he often tries to hide it, of immeasurable compassion. And that is François-Paul Journe himself.

While there are not many things in life I am sure about, I know with absolute resolute certainty that Journe’s legacy will extend beyond the quarter century of his brand’s existence, beyond even his own lifetime and endure forever, so as to place him firmly amongst the handful of watchmaking’s true immortals. Each time I visit his Geneva headquarters, I never fail to be amused by a painting that hangs in one of the conference rooms. It depicts his heroes, Antide Janvier and Abraham-Louis Breguet, together with Journe himself, deep in convivial conversation, aided by copious quantities of wine — a sort of holy trinity or Mount Rushmore of watchmaking’s most singular heroes. But I think if both of those extraordinary men were alive today, after a night of wine and camaraderie, at the break of dawn when the morning light inspires words of truth, they might concede that François-Paul has surpassed even their loftiest achievements. Because for all his watchmaking genius, Janvier was never able to build an immensely successful business in the way that Journe has. And for all his extraordinary marketeering skills, many, including myself, would argue that Journe is a more talented and accomplished pure watchmaker than Breguet.

Francois-Paul's first wristwatch with remontoir d'égalité from 1991

Journe’s palmary achievements are the stuff of legend. His first wristwatch was a tourbillon with remontoir d’egalité or constant force mechanism. When I first met him for the unveiling of this timepiece, he said, “Everyone wants to make a tourbillon wristwatch. But actually a tourbillon has no real purpose in a wristwatch. Putting one inside is like intentionally breaking your leg before running a race.” What Journe meant was that a tourbillon was intended to compensate for errors cause by gravity on pocket watches when they were in the vertical position worn in a waistcoat. In a wristwatch, a tourbillion adds significant weight to a regulator. It has an entire cage structure that the balance wheel is then placed inside. When power reserve diminishes as a watch unwinds, the weight of the entire tourbillon mechanism actually amplifies the errors caused by this diminishing torque. This can be addressed by removing the energy source of the tourbillon from the barrel, such as Journe had done. I asked if a constant force mechanism would solve this issue. He smiled and replied, “Having the remontoir d’egalité is like putting the world’s best brace on your leg.”

Tourbillon Souverain

What I would learn is that Journe is not only a genius, but he also has a remarkable humility about his work. This is important to understand. Because many people mistake Journe for being arrogant. This is utterly incorrect. Actually, Journe is understated about his vast accomplishments and always uses humor to deflect well-deserved praise. He is also an incredibly kind and generous person. He just doesn’t suffer fools, which is to say if you are going to interview him, or rather are lucky enough to have a conversation with him, you better understand what he’s achieved and have some semblance of watchmaking acumen. Because asking him a generalist question like, “What inspires you?” would be akin to walking up to Picasso and asking him, “Why do you paint?” Following up on his first tourbillon, Journe then created the first wristwatch tourbillon with a dead seconds mechanism driven by a constant force device. Eventually, he would discontinue the Tourbillon Souverain in its original incarnation and replace it with a multiple-axis tourbillon driven by a remontoir d’egalité. Amusingly, a multi-axis tourbillon is even heavier than a traditional single-axis tourbillon, and so this watch definitely only works because of his groundbreaking work on constant force devices.

Chronomètre à Résonance

From there, Journe unveiled the first wristwatch successfully implementing the phenomenon of resonance. This was something that he pursued for 14 years. His original experiments reach back to 1984 where he tried to get a pocket watch with two balances to enter into resonance. They didn’t. He explains, “This had to do with me using detent escapements, which in the end were made by hand. The blades for these escapements couldn’t be made with a high enough degree of uniformity.” Journe eventually achieved resonance in 1998. The Résonance watches created by François-Paul represent some of the most iconic timepieces of the modern era. These eventually gave way to a new version that added to the constant force mechanism to both trains.

The

Octa is an extraordinary automatic caliber able to integrate a vast variety of complications, including a chronograph. But Journe truly ascended to horological deity status with the creation of the

Sonnerie Souveraine, the world’s first grande et petite sonnerie incorporating safety systems, making it immune to bad owners, and using an all-new single flat gong. Said Journe in 2006 when he launched the watch, “The objective is to make a watch that even an eight-year-old child could use and not break. The problem with the grande sonnerie is that owners often break them. They pull out the crown when the watch is chiming, for example. I wanted to integrate a safety mechanism so that no matter what you did, you couldn’t break the watch.” Journe also launched the world’s thinnest minute repeater wristwatch (at the time), using the same single banana-shaped gong.

Centigraphe Souverain

The Centigraphe is a marvelous creation. It is a chronograph with a 1/100th of a second hand capable of decoupling from the pinion driving it the moment the chronograph brake is activated. For this watch, Journe was able to make a chronograph capable or reading this micro-division of time without a power hungry balance wheel that vibrated at 360,000vph. He also completely reconfigured the power flow of a chronograph by using the barrel to drive his indications rather than the seconds or fourth wheel, which eliminated the parasitical effect on amplitude.

Journe then created a staggering achievement, the Astronomic, a watch displaying sidereal hours and minutes next to civil time, indicating sunrise and sunset, equation of time and driven by an annual calendar and a hidden tourbillon. Amazingly, these are but some examples of his brilliance. The list is seemingly endless and each act alone should by right engrave Journe’s name forever into the canon of watchmaking’s greatest achievements. Taken together, they form a tapestry of horological riches the likes of which the world had not seen for over 200 years, since the last Stravinsky of watchmaking, Abraham-Louis Breguet, walked the earth.

Chronomètre Optimum

The Chronomètre Optimum is one of my favorite watches of all time. It is a chronometer featuring a constant force mechanism and the implementation of Breguet’s natural escapement. Says Journe, “I conceived of this watch at the same time as the Tourbillon Souverain and the Résonance. It really is a watch that addresses all the issues with basic chronometry by using both a constant force mechanism to remove the regulator from the influence of the barrel, and by integrating this double wheel escapement which needs no lubrication.

Élégante

Perhaps most important is that every one of François-Paul Journe’s achievements, including his game-changing quartz watch, the Élégante, or even his wildly expressionistic outlier, the Vagabondage, has advanced the story of watchmaking in a real way, meaning that it has enhanced the performance, accuracy, reliability, beauty and emotional resonance of contemporary watchmaking, following in the tradition of the 18th century’s greatest masters such as Harrison, Lépine, Janvier and Breguet. While Journe was once a best-kept secret for horology’s most passionate and educated devotees, since the COVID pandemic, where the general watch-loving public had time to educate itself, the world has gone decidedly crazy for François-Paul Journe’s watches. The delta between the supply and demand of these watches has driven secondary values of Journe’s watches into the stratosphere in a way that has eclipsed all others. Proof positive of this was that during the recent period of turmoil and uncertainty brought on by the cryptocurrency crash, political conflict and a banking crisis, a time when we saw the prices of so-called “hype watches” crumble as if previously ensconced in the parapets of the Tower of Babel, the prices of Journe’s watches continued to rise in an unassailable upward trajectory. Why? Because the pure horological merit they possess represents the very antithesis to hype. Indeed, they are perhaps best described as the ultimate anti-hype watches and the world’s greatest repositories of true horological content.

Vagabondage I with a central balance wheel and wandering jump hour display

Perhaps what I love best about François-Paul Journe, as I am lucky enough to call myself his friend, is that he has never lost the wonderful playfulness and child-like humor of the 17-year-old boy shuttling between the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts in Paris and his uncle Michel’s restoration workshop. His enthusiasm for horology and invention remains unabated. He is not motivated by wealth of material possessions. He lives in a normal apartment in Geneva’s Old Town and, every day, he cooks and brings lunch to his mother who lives upstairs from him. He is the same today as the young man that built a tourbillon with remontoir for the collector Dr. Eugen Gschwind so that he could do battle with George Daniels in a game of horological one-upmanship. He is the same today as the young man who after meeting Cecil “Sam” Clutton and feeling an electric bolt of inspiration at the sight of the two tourbillon watches the famous collector would wear, set out to create his own tourbillon, armed with nothing more than the brilliance of his mind, the skill of his hands and a copy of George Daniels’ book.

It is for this reason that, throughout his life, he continued to regard Daniels as a mentor and a spiritual father. On the occasion of the great British watchmaker’s birthday in 2010, which was celebrated with an homage dinner organized by Journe and his partners in London, William and John Asprey, Journe declared: “You have opened the main door to contemporary horology and showed us the path back to authentic watchmaking with innovation sense, in the respect of the grand horological tradition of our great watch masters. He opened the main door; I could only follow in opening others.” On that night, Journe presented Daniels with a gift, a Chronomètre Souverain. As he passed him the watch, he said to Daniels, “Thank you, George, for being the best.”

Daniels said to him and to all the other horological luminaries arrayed around him, “I’m not the best anymore, François-Paul. You are.”

Says Journe, “The fact that he said it in front of others meant a lot to me.” What is Journe working on now? He explains, “I’m creating an escapement based on the detent but [that] eliminates all the problems with that design. It is meant to be an escapement that I can integrate across the entire product line, meaning that every one of my watches will have this unique escapement.” Thus, Journe will follow in the footsteps of his hero George Daniels who, to this day, is the only watchmaker in the modern era who has seen the successful implementation of his signature escapement.

When I ask François-Paul to reflect on his achievements, he says with humility, “Watchmaking is like a long wall. What I have done is brought one or two stones to the wall, which is already not bad as there are many others who have never done even that.” The truth is that it is not two stones that he has added, but an entire parapet, the foundation of which will serve to uplift an entire new generation of watchmakers. And because François-Paul Journe’s greatest achievement has been to uplift the entire world of independent watching now and forever, he is, in my opinion, the Greatest Watchmaker of All Time.

Denis Flageollet: The Creator

Denis Flageollet

To compare anyone to the most accomplished polymath of the High Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci, seems initially like a reach. But the more you spend time with

Denis Flageollet, the co-creator of De Bethune, the more invariable the comparison becomes. Like Da Vinci, Flageollet’s genius expresses itself through both technical ingenuity and aesthetic beauty. So relentless is Flageollet’s quest to invent and create that he will smelt his own alloys from minerals he’s found in his region to handcraft his own watch cases in the forge behind his house. Says Danny Govberg, a pioneering force in the watch industry, “The Leonardo da Vinci of horology is Denis Flageollet. He is a man of incredible depth and creativity. Look at the design of his watches. While the other giants in independent watchmaking generally reference the past, his aesthetic language is totally unique, new and different. It’s modern in a way that other brands aren’t. At the same time, he’s invented so many different ground-technical innovations, like a chronograph with three clutches and the world’s lightest tourbillon, that the underlying substance of his watches is to me unequaled by most of his contemporaries.”

Flageollet has managed to achieve all these because he is the purest watchmaker at heart. Eschewing the limelight and dwelling in remote Sainte-Croix, he pushes himself to the very edge of the horological envelope, transforming tower clocks into insanely complex planetariums and surrounding himself with nature, tapping into its beauty for inspiration. By doing so, he has profoundly and beautifully advanced the history of watchmaking in a uniquely poetic and beautiful way. Says Jean Arnault, Louis Vuitton’s director of watches and founder of the Louis Vuitton Watch Prize for independents, “Denis Flageollet is, from my perspective, very possibly the most purely creative living watchmaker today.”

What is also utterly true is that it is impossible not to be emotionally affected by a De Bethune watch. When you hold one in your hand, be it a DB28 with its exposed balance wheel or a DB25 perpetual calendar, you come face to face with an all-new horological language. It feels bewildering and magical at the same time. The fascinating dichotomy of a De Bethune watch is that it pays enormous respect to the history of watchmaking while looking completely unlike any other watch on the planet. If Flageollet had been a musician, he would have created an all-original sonic art from. He would have been Grandmaster Flash or John Coltrane. As it stands, he is the auteur of a unique and devastatingly seductive aesthetic and technical codex with which he uses to transform metal into shimmering otherworldly, Constantin Brâncuși-like horological sculpture. But the most important thing is that in every instance where a De Bethune has intentionally distinguished and set itself apart from all other watches aesthetically, there is always a fundamental watchmaking rationale for it.

Take, for example, the stunning and unique flame-treated blue color we see on many De Bethune watches. Says Flageollet, “This actually came from a functional treatment. When I had created one of my balance wheels [De Bethune has nine proprietary balance wheels at last count], I wanted to flame treat the titanium arms. I did this to stabilize and protect the material. The process turns titanium into an intense blue hue which I actually loved. So instead of removing the color, I progressively colored more and more parts of the watch blue until I arrived at a fully blued watch. Because of the extensive use of grade 5 titanium, such as for the delta-shaped bridge and the case and lugs of the DB28, I could actually showcase how stunning this color looked.” At last year’s White Party held by sportswear entrepreneur

Michael Rubin, NBA star Kyle Kuzma rocked up wearing my former De Bethune DB28, which has the honor of being the very first watch that Flageollet experimented on with an all-blue hue. Set against a sea of white clothing, the color of the watch was akin to a light beacon, so stunning and vivid is the color, it stands totally apart from any other watch.

Wei Koh’s former pièce unique De Bethune DB28

Owners of the DB28 will know that the ultra cool leitmotif found at six o’clock on their watch is the world’s first three-dimensional moonphase indicator placed inside a wristwatch. This miniature sphere was handcrafted from two halves — one of palladium and the other of steel. It was then soldered together, polished until it is seamless and mirror-like, then subjected to a flame treatment so that only the steel half turns blue. This tiny masterpiece of craftsmanship is then inserted into the watch and displays the phase of the moon with remarkable accuracy. Says Flageollet, “The three-dimensional moonphase indicator was inspired by tower clocks. In medieval times, these huge tower clocks were how people told the time. There were often indications like phase of the moon because these agrarian cultures would need the information for planting crops and harvesting, etc. I thought to myself, why can’t we place this inside the small dimensions of a wristwatch?” Collectors are often fascinated by this mechanism thanks to its futuristic, avant-gardist execution but, as with everything Flageollet does, its roots are powerfully embedded in watchmaking history.

De Bethune Perpetual Calendar DB15

To borrow a Chuck Yeager analogy, the DB15 for its pure inventiveness, was Flageollet’s equivalent of breaking the sound barrier. The sonic boom that reverberated in my mind when I first set eyes on it was simply staggering. The triple pare-chute system utilizes a balance bridge that has two additional shock absorbers on each fixing point for the bridge. Combined with the anti-shock fitted to the balance staff, you have the maximum amount of isolation of the regulator from the vibrations and micro-shocks experienced by a wristwatch on an almost constant basis.

The balance wheel, a round rim with spoked arms that oscillates first one direction then the other, is the heart of the watch. Combined with the escapement that regulates its heartbeat, the balance wheel is the device that literally divides time down into fractions of a second and provides the accuracy for your watch. Since time immemorial, the vast majority of the watch industry has purchased its balance wheels from a company called Nivarox owned by the Swatch Group. Flageollet was the very first watchmaker to craft his own. Since he was creating it from the ground up, he unleashed his wonderfully artistic sensibility on it, designing first a balance with titanium arms and tiny torpedo-shaped platinum weights. He explains, “The shape of these weights was to reduce aerodynamic turbulence.” From there, he eventually gravitated to a full silicon disk with a gold or platinum rim. He explains, “The objective was to create a balance wheel that was as light as possible, but with as high of a moment of inertia as possible.” This gave way to a spoked silicon model with holes in the spoked arms and, finally, another titanium armed example.

DB28 Kind Of Blue Tourbillon Meteorite with an ultra-light 30-seconds tourbillon made of titanium and silicon and a 5 Hz balance

Says Tim Mosso, “The fact that Denis has invented nine completely unique and different balance wheels positions him as one of the most important and creative watchmakers of all time.”

Not content to develop all-new oscillators, Flageollet also turned his attention to the hairspring fixed to it and powering and controlling the uniformity of its movements. Says Flageollet, “For many years, watchmakers used the Breguet or Phillips terminal curve.” This is an overcoil where the end of the spring is bent on top of the coils to help with concentric breathing. Flageollet continues, “This design means that the hairspring has to occupy a certain volume because its height is increased. I wanted to create a terminal curve that would achieve the same results regarding concentric breathing but that was on one level.” Initially, Flageollet devised the De Bethune terminal curve out of one piece of silicon. But because of a patent on the oxide treatment needed to allow silicon to be stable at different temperatures, he had to put that design on the shelf. Instead, he created a metal hairspring where the final bend is a second piece of metal with a greater thickness and following a unique faceted shape. The result is the same concentric breathing, just with a two-part hairspring.

However, to me, Denis Flageollet’s crowning achievement is his tourbillon. He says, “What was clear was that Breguet had created the tourbillon to compensate for errors caused by gravity on the regulator of a pocket watch worn in the vertical position in a man’s waistcoat. There were many tourbillon wristwatches, but I felt none of them had actually addressed the problems posed by a watch worn on the wrist — that it is subjected to a great deal of shock and adopts an infinite number of positions throughout the day.” Following up on his pioneering work on balance wheels, Flageollet completely revolutionized the concept of a tourbillon. First, he created a hyper minimalist and ultra light cage weighing an almost unbelievable 0.18 grams fabricated from titanium and silicon. Second, he created a balance that vibrated at the high speed of 5Hz and a cage that completed a full rotation every 30 seconds as opposed to the normal one-minute speed. He explains, “All three of these elements combined creates a tourbillon that is ideally optimized for a wristwatch. The light weight, the high vibrational speed and the fast-rotating speed gives it far greater autonomy from shock than a traditional tourbillon.”

Kind of Two

Amongst Flageollet’s other signature inventions are a fantastic dead seconds tourbillon, a series of double-sided wristwatches called

Kind of Two, a diving watch fitted with mechanically powered LED lights, a stunning 40mm perpetual calendar with moonphase display. However, what you might not know is that, as you read this, Flageollet is working on one of the single greatest horological achievements of all time. In 2025, he will write an all-new chapter in watchmaking history. He is also — just for fun — working on restoring the clock in Notre Dame Cathedral that was damaged in a fire in 2019. Because of his single-minded pursuit of beauty, poetry and real watchmaking, and for his ability to evoke emotion unlike any other watchmaker I know, Flageollet is independent watchmaking’s very own poet laureate and its most inventive Creator.