Opinion

Swiss Made + The World

Opinion

Swiss Made + The World

While legal protection of the Swiss watch industry is important, in many ways, the legal definitions laid down in 1971 (and strengthened most recently in 2017) are as much about telling a particular story as they are about protecting their turf. Overwhelmingly, the Swiss are recognized as the preeminent makers of fine watches, and that’s been the dominant narrative for the last 100 or so years, give or take. But if you take a moment to think about the words on the dial, and why they’re there, you’ll realize that they emerged in response to global challenges to Helvetic hegemony. A fascinating by-product of this dominance has been a rich global culture of watchmaking, with world-class watches being made in places as far-flung as Finland and even the watchmaking wasteland of Australia.

"Swiss Made" — the two words now synonymous with quality and reliability in timepieces

How the Swiss watch came to be

While the Swiss certainly dominate the market, they weren’t the first and, for a long time, they weren’t the best when it came to the watch game. Germany is widely regarded as being the first country to produce early versions of watches back in the 16th century. In the centuries following, watchmaking coalesced around centers of scientific excellence. The Dutch made great watches, thanks in no small part to Christiaan Huygens’ work on pendulums and the balance spring. France had its own horological superstar in Abraham-Louis Breguet, but he is only the most famous name in a talented pack. Across the Channel in England, men like Robert Hooke, George Graham and John Harrison each made their own impermeable mark on the history of watchmaking. It might sound like heresy, but in the era of these giant figures of timekeeping, the Swiss had a reputation for producing lower quality “fake” watches in the style of English or French pieces. What turned the Swiss watch industry onto its present course was mass production. Throughout the 19th century, the decentralized model of the Swiss industry gradually aggregated, first using an établissage system, where watch components made by individual specialists would be assembled at a central point. This system was further refined when dedicated factories entered the scene starting in 1832 with Agassiz & Co. in St. Imier — a factory that would become Longines. The years rolled along, as did the sophistication and centralization of the Swiss watchmaking infrastructure. Increased industrialization, new technologies, booming demand and an industry relatively uninterrupted by successive world wars left the Swiss in a strong position.

Challenges near and far

An early shift to industrialization worked well for the Swiss, but they weren’t the only country to go down this route. The United States of America, famous for its factories, built up an impressive infrastructure in its own watchmaking heartland of Illinois and Pennsylvania. Driven by the rail boom with its twin impetus of increased mobility and the very real need for precise, reliable timekeepers, brands like Waltham, Elgin, Hamilton and Bulova exploded in the second half of the 19th century, with an industrialized approach. American watches were competitive with the Swiss at the turn of the century, but a series of economic setbacks such as the Great Depression hampered the industry. World War II gave American producers a temporary reprieve, but output was typically limited to military equipment, and in the economic boom and rapidly changing society of the ’50s and ’60s, American brands failed to compete with the Swiss and gradually shut up shop.

American Waltham Watch Co. "Crystal Plate" Movement; White Metal (Image: Antiquorum)

Elgin B. W. Raymond Men's Watch in 14KT Yellow Gold (Image: Chrono24)

Hamilton Railway Special Pocket Watch circa 1940s

Bulova Open Face Gold Filled Pocket Watch (Image: www.rubylane.com)

Seiko Sportsmatic 5 Vintage 1965 Silver 36mm Automatic (Image: Carousell)

The return

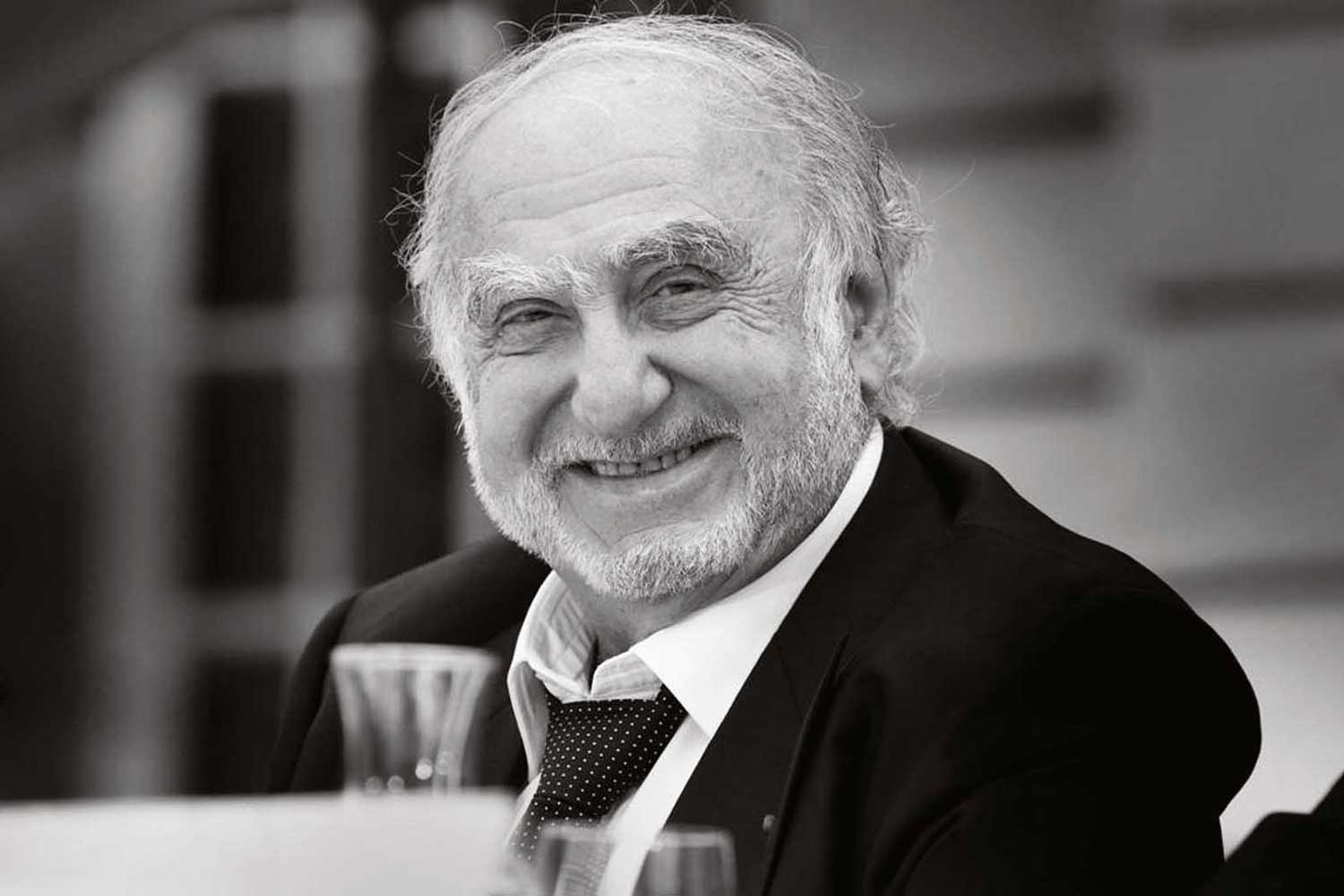

For a while there, the Swiss shoring up their national watchmaking identity looked like a last ditch attempt. But then something amazing happened. The Swiss embraced a cheap plastic watch powered by a battery. A watch called Swatch. More importantly, Swatch was embraced by the world. The architect behind Swatch, which succeeded thanks to its marketing, was Nicolas G. Hayek. Not content to create one successful brand, Hayek resolved to use the success of this fantastic piece of plastic to essentially save the Swiss watch industry. Hayek purchased numerous companies and merged them under the umbrella of the SMH (later Swatch) Group. This group approach allowed previously individualist brands to survive and even thrive under Hayek’s vision of streamlined watch development and production. While Hayek was the standard- bearer, other forward-looking figures like Jean-Claude Biver, Rolf Schnyder and Günter Blümlein were busy reviving washed-up brands and trying to make mechanical watches cool again.

The cheap and cheerful Swatch isn’t exactly the first thing that comes to mind when you think about a Swiss Made timepiece, but this plastic watch is widely credited with saving Switzerland’s watch industry

Nicolas G. Hayek

The industry icon Jean-Claude Biver

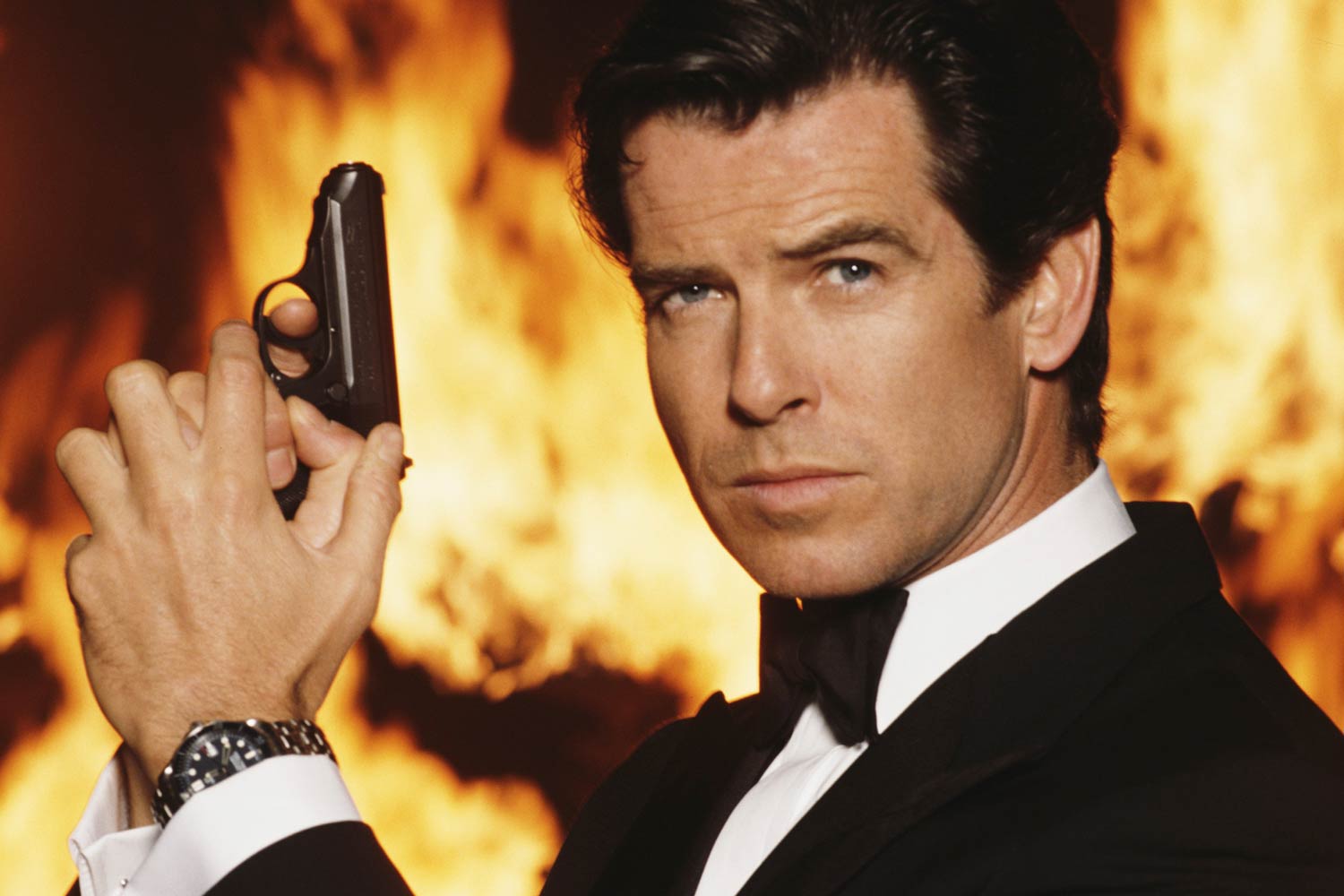

Pierce Brosnan posing for a poster for the 1995 Bond instalment, GoldenEye

Sylvester Stallone in the movie Daylight wearing a Pre-Vendome Panerai, along side Amy Brenneman

A new world order of watches

It’s worth noting the role the rest of the world played in this narrative of Swiss excellence. While no one can doubt the importance of the infrastructure and institutional knowledge that underpinned the renaissance, many of the mechanical watch’s greatest advocates weren’t Swiss. Italy and Japan were hugely significant markets that saw the potential of legacy brands when no one else did. Savvy and passionate retailers like Goldpfeil in Germany and The Hour Glass in Singapore financially supported these brands at a critical time. Nascent watch publications like Orologi in Italy paved the way for a new way of talking about watches, supported by a global network of collector communities. And then there are the watchmakers themselves. While Switzerland is the beating heart of the mechanical watch industry, not all the people creating the calibers under the “Swiss Made” label are necessarily Swiss. Take, for example, George Daniels, the famously irascible English watchmaker who, after inventing his revolutionary co-axial escapement, spent several bitter decades convincing the conservative Swiss establishment to take a risk on something new.

George Daniels was the first watchmaker to have mastered 32 of the 34 crafts considered necessary to build a watch

Swiss Made might well be the world’s most well- recognized (and most potent) label of origin. But it doesn’t show the full picture, nor did it emerge from a vacuum. The Swiss industry was built off the back of — and in response to – global innovations. A long, uninterrupted period of sustained growth allowed Switzerland’s watchmaking industry time to mature and develop — and still, it was near-fatally crippled by cheaper, high-quality competitors, namely from Japan and, generally, from Asia.

Even taking the bricks and mortar of this highly industrialized business out of the way, Switzerland, because of its size and scale, attracted the creme de la creme from around the world. If you wanted to work at the highest level, you had to travel to Switzerland. But Swiss watches aren’t the best simply because they are made in Switzerland. They are the best because Switzerland has, one way or another, attracted the best.

This situation isn’t going to change any time soon. Switzerland is still the best place to nurture talent, and the legacy infrastructure would be hard for anyone else to compete with. But we are witnessing, right now, one important and exciting shift, one where watch producers and consumers are confident and educated enough to understand that a great watch doesn’t need to be defined by Swiss Made on the dial.