Audemars Piguet

Mr Talking Hands On: That ’70s Show

Audemars Piguet

Mr Talking Hands On: That ’70s Show

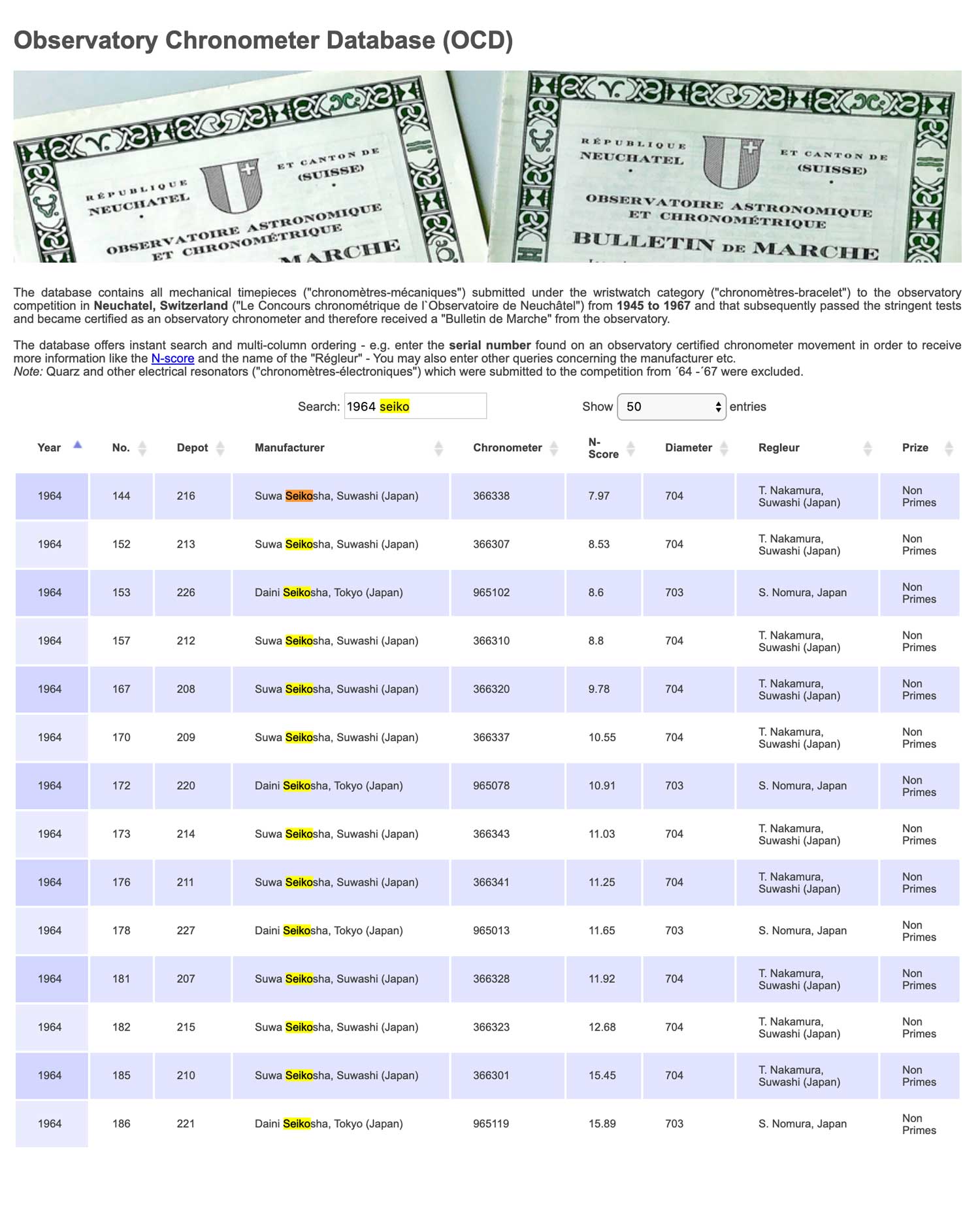

In the 1970s, for the Swiss business of watchmaking, adapt and survive was very much the name of the game. You could say it came on quite suddenly, but it didn’t really. When plucky Japanese watchmaker Seiko started emulating its Swiss heroes, entering the revered Neuchâtel Observatory competition for mechanical wristwatches in 1964 and not even passing the tests, nobody thought much of it. Big mistake.

Seiko's 1964 entries to the observatory competition in Neuchatel, Switzerland ("Le Concours chronométrique de l`Observatoire de Neuchâtel"), weren't the most encouraging with the highest scoring entry ranking in at 144 (Source: observatory.watch)

Yes, the Swiss won with a quartz movement. And the best of the rest, with a mechanical movement, was Seiko. Needless to say, Seiko had the last laugh with the 1969 Astron, a quartz watch of its very own that sent the Swiss watchmaking industry into turmoil. No longer were complex mechanical watches needed. Although initially expensive, the quartz watch became incredibly affordable, and that meant, for the Swiss, sink or swim.

The overall damage was devastating. Employment in watchmaking fell to a third. For companies mass producing watches like Omega and Rolex, there was a scramble to release quartz watches of their own, built with a hope and a prayer that the reputations these brands had earned over the decades would be enough to bridge the vast difference in price between their watches and Seiko’s.

For companies like Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe, however, things were very different. And worse. As businesses making low volume, high complication wristwatches and even pocket watches, they did not have the budget and resource to diversify. Patek Philippe had experimented with electronic clockmaking as very expensive custom builds for businesses like the BBC, but this was different. Affordable, mass-produced quartz watches were beyond the realms of possibility.

It doesn’t matter whose name is on the (usually blue) dial, you’ll know a ’70s watch when you see one

It doesn’t matter whose name is on the (usually blue) dial, you’ll know a ’70s watch when you see one

A new concept of luxury

Through the ’50s and ’60s, a cultural shift saw people with the new luxury of leisure time and money to spend. The youth of the era threw off the stuffy formalities of their parents and followed instead in the footsteps of idols James Dean and Steve McQueen, who presented a new, casual way of life. Watch trends followed suit; nothing went better with rugged, simple jeans and T-shirt than a watch built for function rather than form. The Rolex Submariner, as rugged and functional as watches go, became an unlikely hero. Ironically, the watch that offered nothing by way of styling emerged as a cultural icon. The obsession with the stainless steel sports watch began.

A trend means popularity, popularity means social status, and social status means money. Here’s where Audemars Piguet, a business laid on a foundation of hand-built traditional watches, said screw it — or words to that effect — and put everything it had and more on red. The business had been struggling for a long time with the Great Depression culling the demand for the incredibly complicated pocket watches it was so well-versed at making and so, in 1972, the company made a last-ditch attempt at saving itself.

Led by the charge of the 1972 Royal Oak, that ’70s look was quickly mimicked by brands far and wide

But now that the technological benchmark had been surpassed, the Royal Oak would need to present a different appeal. So, here’s what Audemars Piguet did. They didn’t do complication, didn’t do tradition; they made a watch so big, bold and outlandish it could be recognisable from a mile away. That was step one. Step two: doubling down on its own bet, was to price the Royal Oak at a level no one had ever seen before. It wasn’t just expensive, it was ludicrous. Ten times more expensive than a Submariner, more expensive even than Audemars Piguet’s own gold watches, it was a price only a very few could pay.

It didn’t even have an Audemars Piguet movement in it. A decision that was likely heart-breaking for the manufacturer, the beautiful, complex works of art it had built a reputation on for almost a century were eschewed for an ultra thin automatic calibre from Jaeger-LeCoultre. The only complication was a date. It didn’t even have a seconds hand. And that’s because time was the least important thing about it.

The Royal Oak sounded like a failure waiting to happen. The aghast press of the period certainly thought so. Who on earth would pay 10 times the price of a Rolex to wear an outrageously styled watch — in steel, no less, with not a drop of luxury in sight? The answer was everybody. Audemars Piguet couldn’t make enough of them. But why?

The answer, as it often is, is simple. If you have money and you want people to know it, what better way to demonstrate that than by wearing a watch recognisable a mile away as the one that costs 10 times the price of a Rolex Submariner — despite not having any complications, not being made of precious metal, and not even having an Audemars Piguet movement inside? The Royal Oak was genius, an idea as outrageous as the watch itself. Not only did it turn the tide for Audemars Piguet, but the Swiss watch industry as well. A Swiss watch was no longer a practical purchase; it was a luxury one.

Of course, every man and his dog aboard the sinking ship HMS Old School Watchmaking wanted in on the action. The list of brands that saw the Royal Oak’s success and went on to brief their product development teams by pointing at it and saying, “Do that”, was plentiful. Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin were the best-known offenders, but you can also count on Rolex, IWC, Baume et Mercier, Piaget, Girard-Perregaux and, indeed, Bulova, whose own Royal Oak — yes, same exact name — was less inspired by the Audemars Piguet original than it was a complete rip-off.

Even the most historic watchmakers like Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe jumped on the bandwagon

Even the most historic watchmakers like Vacheron Constantin and Patek Philippe jumped on the bandwagon

My theory is that it’s a piece of history that generations of people who remember its appearance the first time around can now afford. So much of watchmaking is tied to heritage and with memories of key moments like the dawn of the Submariner slipping off this mortal coil, the upheaval of the Quartz Crisis is the next prominent historical moment in watchmaking history books. Either that or it’s a Kim Kardashian situation — somehow popular, but nobody quite knows why….

If it really is a bit of a mystery, that might explain why Mr Stern is so anxiously trying to avoid the Nautilus becoming an overly prominent part of the Patek Philippe collection. A not-so-subtle jibe at Audemars Piguet’s reliance on the Royal Oak, his stance on the Nautilus not overwhelming the brand itself speaks volumes to the unexpected dominance of both these watches. Perhaps this marks a turning point in the industry yet again, one we won’t be able to see until the dust has settled? The race to climb aboard the bandwagon has been as hotfooted as the California Gold Rush, and we all know how that ended up. Something I have noticed, however, sitting quietly in the corner and avoiding its legitimate claim to Genta fame, is IWC. Do they know something we don’t?