A deep dive into the fine watchmaking of Moritz Grossmann.

When talk veers towards German fine watchmaking, it’s the name A. Lange & Söhne

that naturally comes up tops. But for some years now, its neighbor in the unassuming hamlet of Glashütte,

Moritz Grossmann, has been steadily asserting its presence, carving its own niche in the horological landscape with its remarkable level of craftsmanship and a distinctive approach to movement making. A modest production firm, it specializes in the same caliber of watchmaking that its renowned counterpart is celebrated for but on a significantly smaller scale. In fact, in certain aspects of craft, it even emerges as the standard bearer.

Its story is one not hard to like, having been founded by Christine Hutter, a Eichstätt-born watchmaker and former employee of both A. Lange & Söhne and Glashütte Original. Hutter’s fascination with mechanical watchmaking took root soon after she graduated from university in 1986. She immersed herself in an apprenticeship under the guidance of master watchmaker Wilhelm Glöggler in Munich where she restored pendulum clocks, pocket watches and chronographs. Graduating at the top of her class, Hutter’s journey led her to Glashütte, the revered hub of German fine watchmaking. She began her career at Wempe Germany’s largest luxury watch retailer, then moved to Maurice Lacroix and, in 1996, to Glashütte Original and ultimately A. Lange & Söhne. During her time in Glashütte, she discovered the grand name of Karl Moritz Grossmann (1826-1885), the son of a mail sorter who became one of the founding fathers of the German watchmaking industry along with Ferdinand Adolph Lange, Julius Assmann, and Adolf Schneider.

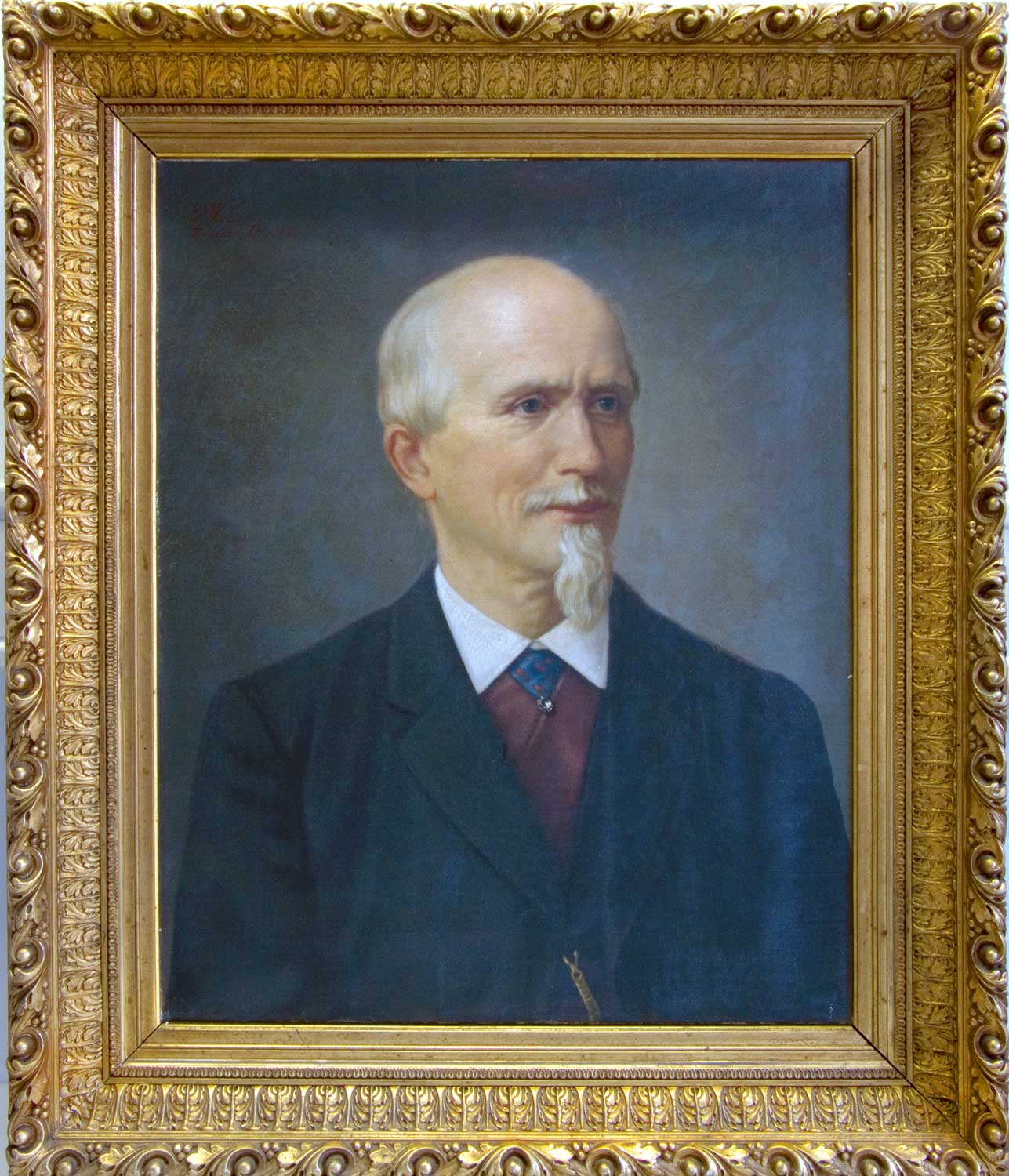

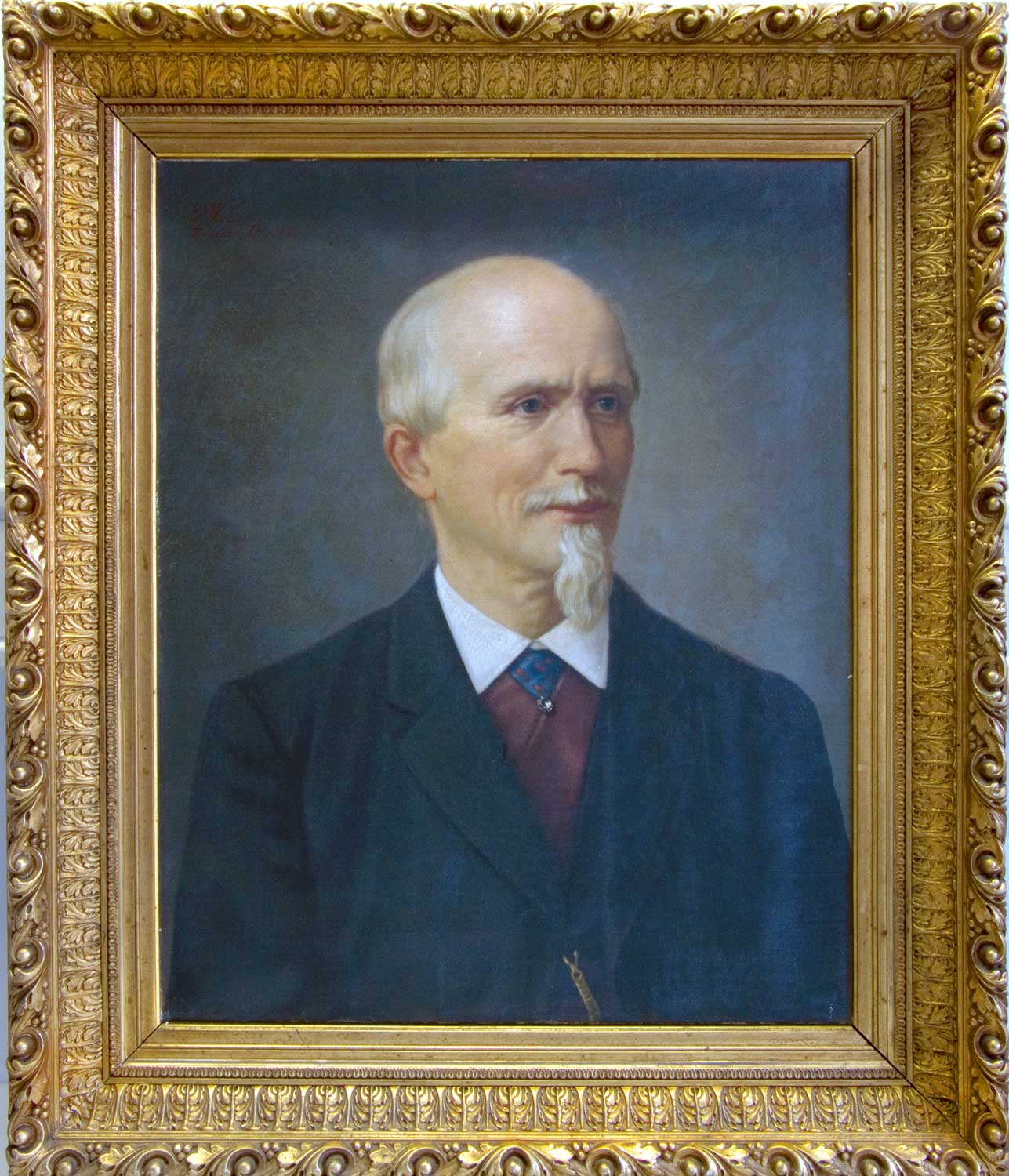

Moritz Grossmann

Christine Hutter

Like Ferdinand Adolph Lange, the work of Karl Moritz Grossmann had done so much to propel both the advancement of horology and the prosperity of Glashütte. At the encouragement of Lange who founded A. Lange & Söhne nine years earlier, Moritz Grossmann established his own watchmaking company in 1854, where he developed precision lathes for watchmakers in Glashütte and later concentrated on lever escapements and the optimization of pivoted detents for chronometers. The company later became renowned for producing high-quality pocket watches and marine chronometers.

A gold hunter-cased Moritz Grossmann pocket watch with a white enamel dial that is swept by finely executed blued steel hands

Above all, Grossmann was chiefly remarkable for his extraordinary industry and unwavering passion to elevate the standards of watchmaking in Glashütte. He conducted courses, delivered lectures, and was a voluminous writer who contributed to both domestic and foreign specialized magazines. Furthermore, he authored and translated books on the subject, including the multi-volume anthology “Lehrbuch der Uhrmacherei” (Textbook of Watchmaking) by Claudius Saunier. One of his most significant accomplishments was his 1866 treatise on the detached lever escapement, on which the Swiss Lever escapement present in a majority of watches known today is based and with which Grossmann became the very first German contestant to win a competition tendered by the British Horological Institute. His philosophy of mechanics is also explained in detail in his book On the Construction of a Simple But Mechanically Perfect Watch (1880). In 1978, to ensure a continuing supply of qualified watchmakers, he founded the German School of Watchmaking in Glashütte.

While the school thrived for more than 114 years, sustaining the industry through rapid growth, his own watchmaking enterprise came to an end upon his untimely passing in 1885. Only in 2008 did the name Moritz Grossmann resurface in the world of watchmaking. With the support of her family, Hutter acquired the rights to the name of the 19th-century horologist and assumed the role of its spiritual successor.

The Moritz Grossmann manufacture in Glashütte

By the year 2010, she had acquired a piece of land and enlisted the expertise of Flender & Drobig, esteemed German architects, to conceive a manufacture that embodied her unique blend of reverence for tradition and progressive vision. The launch of the BENU which contained the impressive calibre 100.0 later that year marked the start of a range of watches that in terms of construction and finish would come to rival the best of German – and Swiss – watchmaking.

Moritz Grossmann Benu in platinum

Today, with a team of approximately 40 skilled watchmakers, Moritz Grossmann produces no more than 500 watches a year. In terms of dial work, the watches adhere to a timeless Glashütte aesthetic. No detail is superfluous; instead, an exemplary level of meticulousness is expended on the essentials. But what truly sets Moritz Grossmann apart is the amount of effort devoted to crafting hands internally and manually. In contrast, other notable brands do not produce their own hands, underscoring the level of control and artistry that Moritz Grossmann exhibits in their production. Crafting a single set of hands from start to finish is a meticulous process that demands an entire day of dedicated work from a watchmaker.

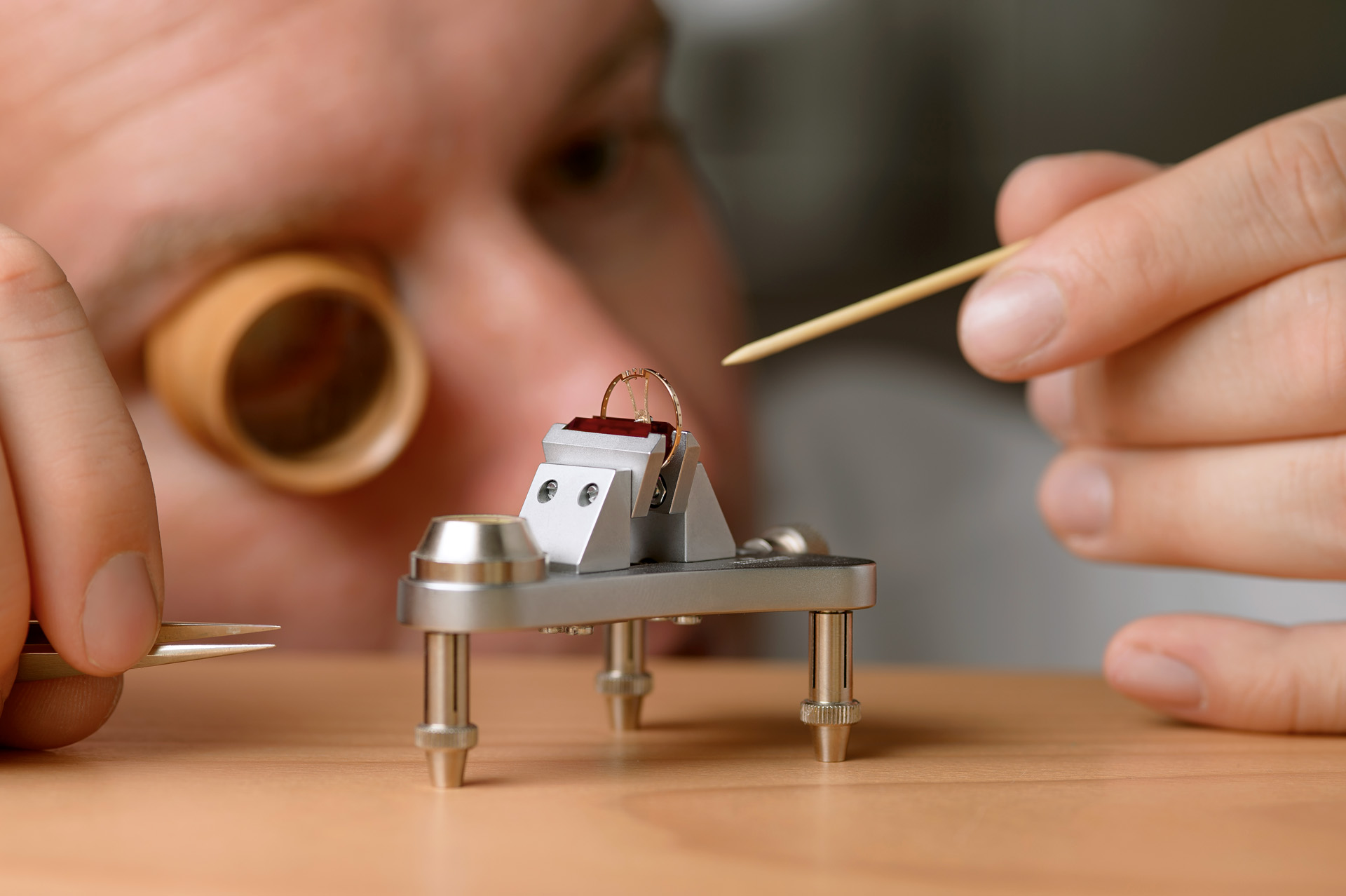

Each hand is finely crafted in-house and attached to a hub that undergoes bevelling and polishing as well

The process begins with precision cutting the contour of the hands from a flat blank, followed by shaping them into their exquisite three-dimensional form using diamond files. Next, the hands undergo hand polishing using a wooden wheel. It’s worth noting that each hand has its own hub that is bevelled and polished, giving it a distinctly three-dimensional appearance that sets it apart from its competitors. Finally, the tip of each hand may be delicately bent to align perfectly with the minute dial, eliminating any potential parallax.

The hands are filed to achieve their remarkable shape and then polished

The edges of the hands are polished with a polishing wheel which demands great control

Each hand is attached to its hub by a press fit

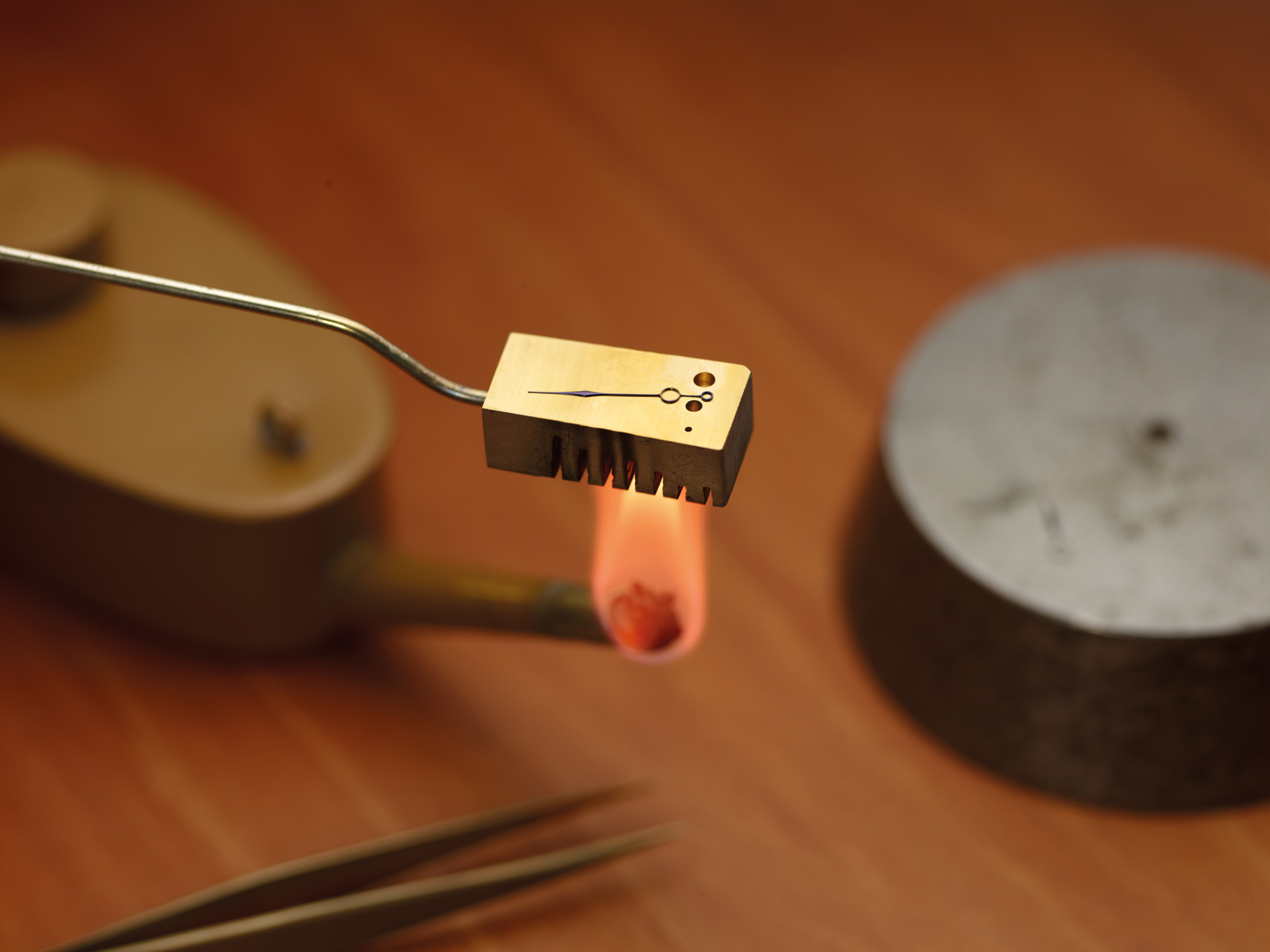

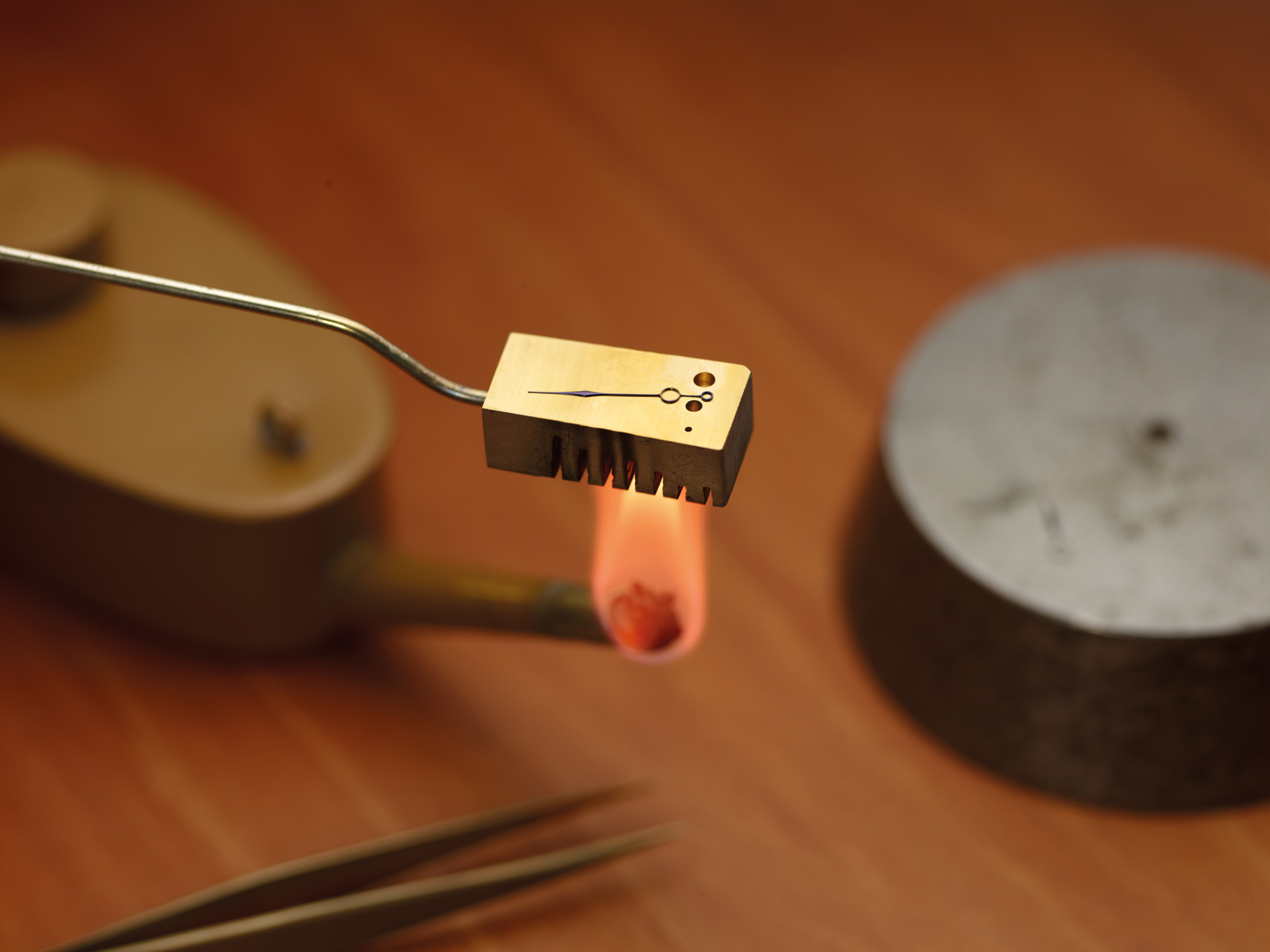

If the hands undergo the process of annealing, which involves heating them to a specific colour, it is the final step in the production. Instead of the customary blue chosen by most watchmakers, Moritz Grossmann employs a distinctive in-house colour known as brown-violet. Achieving this colour requires the watchmaker to carefully heat the hand to a temperature of approximately 270°C, with a tolerance of only 5°C. However, there is a risk involved, as any mishap during this crucial step could result in the entire effort up to that point being rendered futile. It is also worth remembering that Moritz Grossmann produces some of the thinnest hands in watchmaking where each specimen is ground and polished by hand to its final, needle-thin form that measure a mere 0.1mm in width at their narrowest point.

Finally, the hands are annealed over an open flame to a beautiful brown-violet tone

A closer look at the Moritz Grossmann Benu 37 Steel with Grand Feu Enamel Dial for Revolution & The Rake's grand feu enamel ivory dial and the watchmaker's incredibly delicate hands heat treated in their signature colour

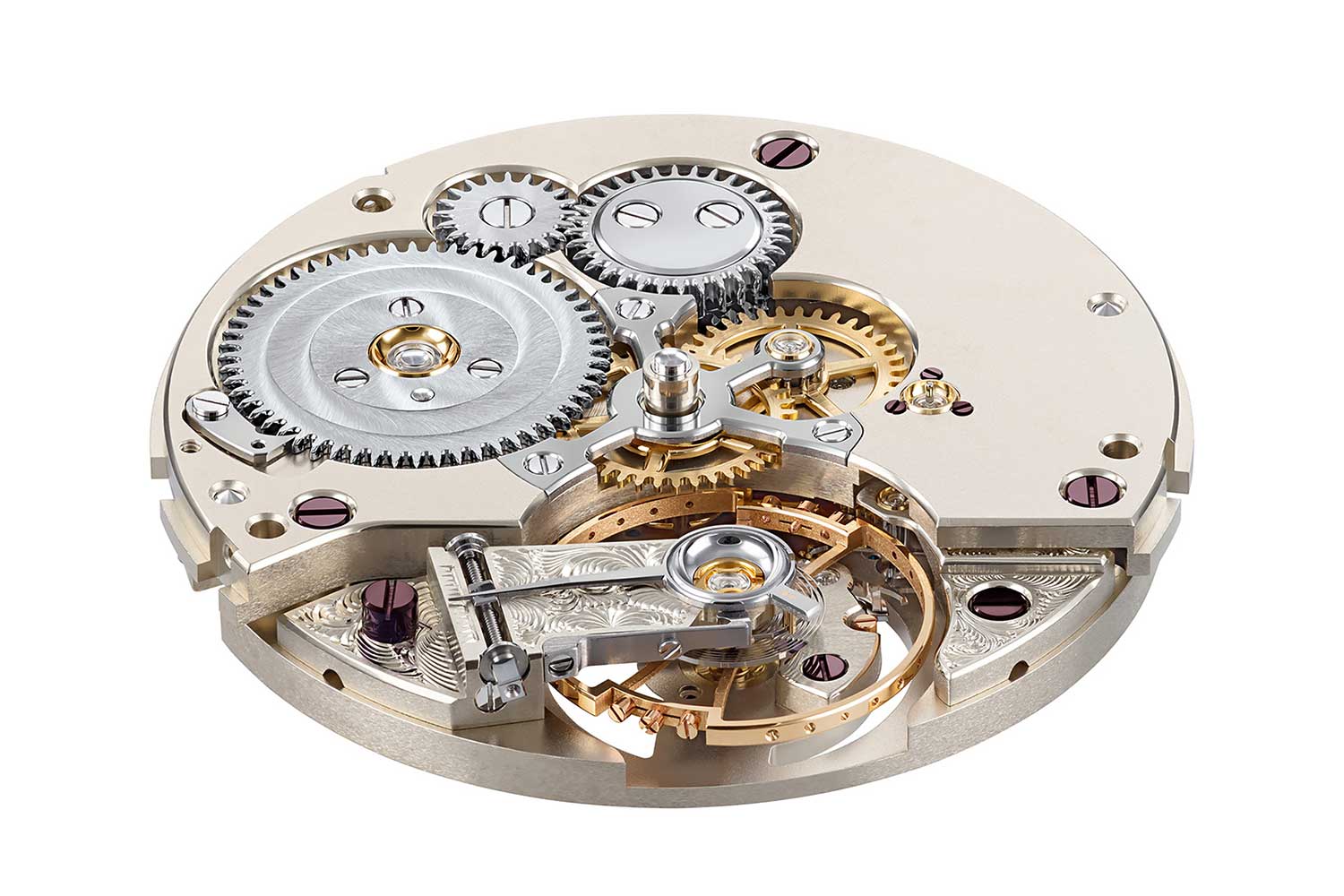

As for their movements, they adopt an anachronistic pillar-and-plate construction in which the going train is sandwiched in between a main plate and a two-third plate, held together by German silver pillars supporting the two plates at their peripheries. This construction dates back to the 17th century and fell by the wayside with the advent of the Lépine calibre in the mid-18th century which replaced the two plates with a single base plate onto which the wheel train is secured with independent bridges. Nevertheless, the pillar-and-plate construction endured in clocks and marine chronometers as the larger size of the movement parts in these timepieces rendered the milling of a solid block of brass to accommodate the parts simply impractical. The pillar construction method, like the three-quarter plate construction, presents additional challenges during movement assembly as all the upper pivots for the gears in the going train must align precisely with the upper jewels.

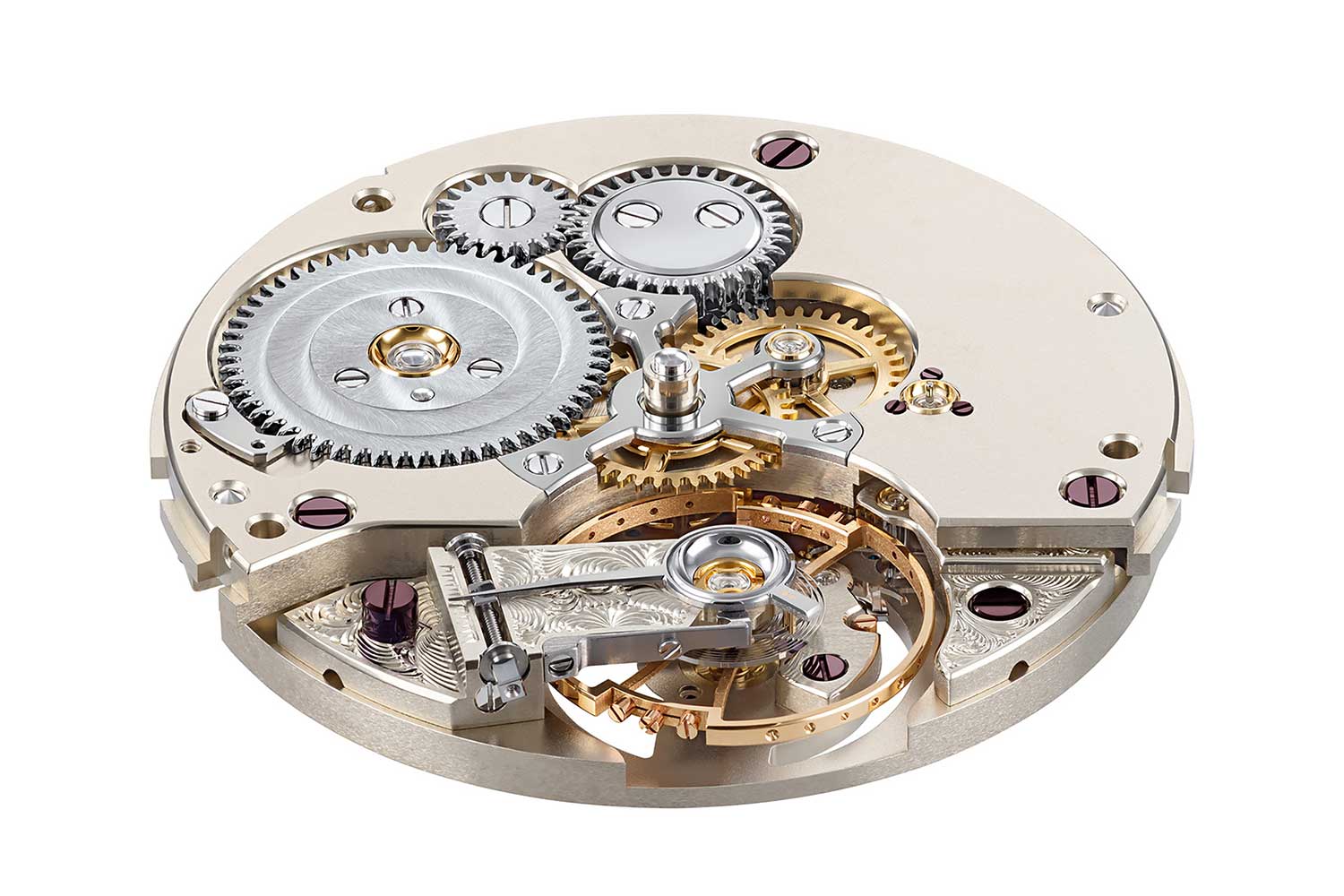

The beautifully constructed and finished Caliber 100.0

Note the contoured German silver pillars between the plates

All the train wheels are crafted from ARCAP rather than brass. ARCAP is an antimagnetic alloy composed of copper, nickel, and zinc, known for its lightweight, corrosion resistance and remarkable tensile strength.

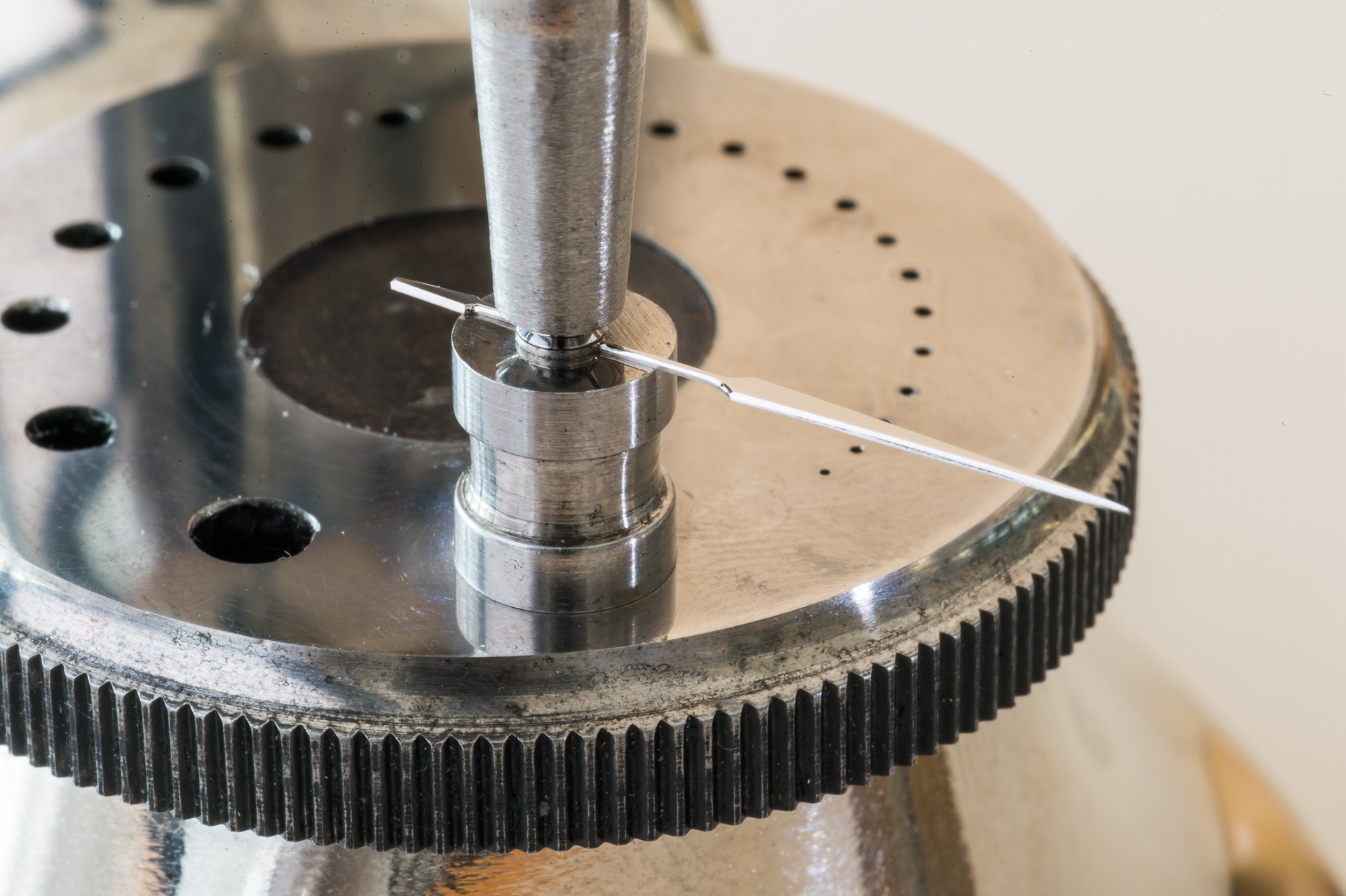

Generally, all Moritz Grossmann movements replicate the formula adopted in marine chronometers to obtain balance power by incorporating an extra-large balance wheel that has a traditional beat rate of 18,000 bph, or 2.5Hz. The balance wheel was developed in-house and was designed with poising screws on two recesses on opposite sides of the rim. Due to the recessed screws, the balance wheel can be made larger, occupying the maximum available space. Consistent with the traditional chronometer principles on which it is built, the hairspring is equipped with a Breguet overcoil. An elaborate, 12-part index regulator is used to adjust the hairspring. The balance cock features a transversal bore with a deep-threaded micrometer screw, which remains exposed. The tapered end of the index tail engages with the screw’s thread. By turning the screw, the index pointer is affected, thereby adjusting the active length of the hairspring and consequently modifying the oscillation period of the balance.

The 107.0 with an inverted construction that powers the Backpage. Note the numerous inward angles on the bridge that supports the motion works

Beyond their construction, the movements are very visually appealing as well. The brand makes judicious use of colour in terms of materials. Polished gold chatons, perfectly annealed brown-violet screws and white sapphire jewels adorn German silver movement plates to create a striking visual composition that provide a beautiful contrast to their restrained, classical dials. Notably, inspired by historic Grossmann pocket watches, the brown-violet screws and the gold chatons that hold the white sapphire bearing jewels are raised, adding depth to the movement while also enabling the jewels to be safely removed and cleaned without risk of damage to the plate when resetting them.

The brown-violet screws and the gold chatting are elevated, providing a sense of depth to the movement. This also allows for safe removal and cleaning of the jewels without the risk of scratching the plate

Due to the fiendish construction and the relative softness of German silver as a result of its high copper content, every movement undergoes a meticulous double assembly process. First an initial assembly for mechanical evaluation takes place, whereby the endshake of the train wheels are adjusted, followed by the adjustment of the escapement and the truing of the balance. Subsequently, the movement is then completely disassembled and the individual parts are decorated before the final assembly.

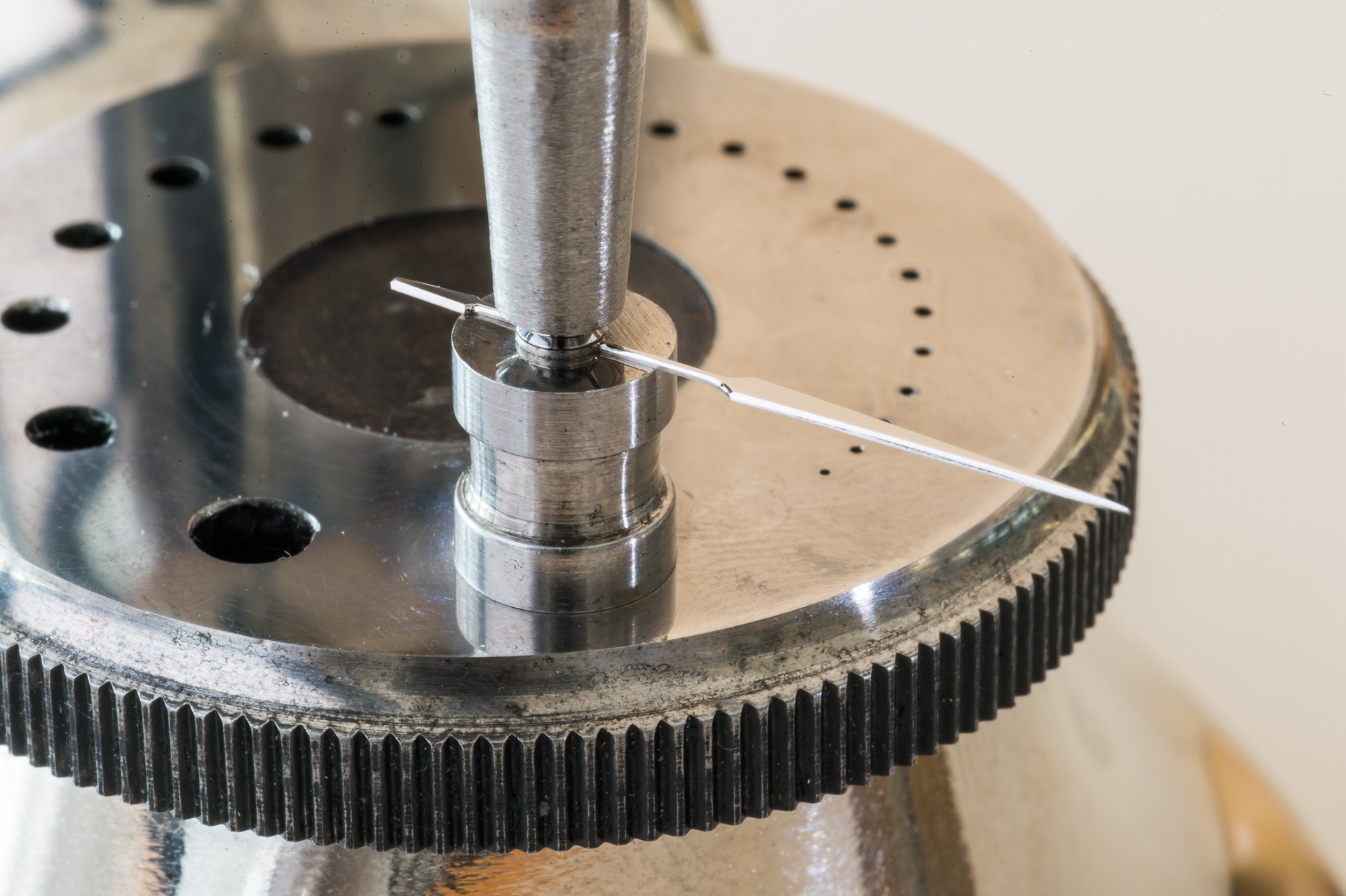

The balance wheel is spun on a poising tool to check for poise errors

As a small production company dedicated to upholding Grossmann’s philosophy of simple, impeccably engineered watches, the brand primarily focuses on classic time-only watches, which are available in a variety of guises, small complications such as the date, power reserve and GMT, as well as watches that are nominally time-only but showcase clever mechanics such as the Backpage with an inverted movement, and the Hamatic, an ingenious and intriguing take on the hammer winding system.

The elaborately constructed Caliber 106.0 in the Hamatic features a swinging weight that triggers a pair of pawls to engage with the teeth of the winding wheels, which wind the mainspring. Image: Wanyu Lee (IG: Deletrium)

When the brand does delve into complications, they are typically executed in as exotic a fashion as possible such as the recently launched Universalzeit, in which six time zones are displayed digitally in apertures with the city names marked on a world map.

Moritz Grossmann Universalzeit (Image: Revolution©)

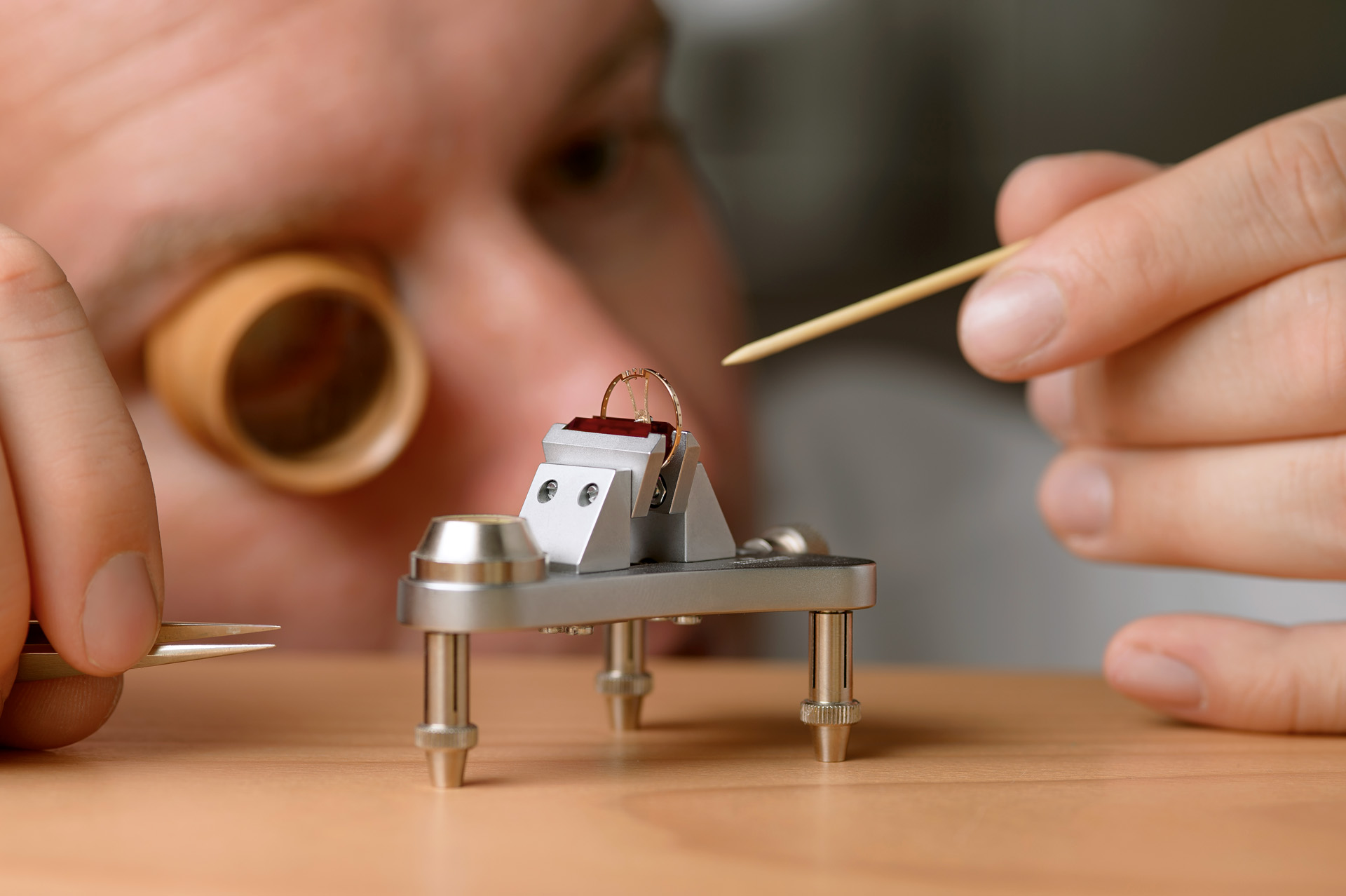

The brand’s most complex watch to date, the Benu Tourbillon, on the other hand, is a stop-seconds flying tourbillon that incorporates a brush made of human hair at the end of the brake lever. The cage’s pillars are designed with a triangular profile, ensuring that even if the brush accidentally falls against one of them, the hairs will separate and maintain contact with the balance wheel. Additionally, it is a slow tourbillon that completes a rotation in three minutes, which is, if anything, even rarer than stop-seconds tourbillons. In contrast to the standard one-minute tourbillon, it requires a different gear ratio that necessitates the placement of gears within the tourbillon cage. This subtle reconfiguration results in a more visually intricate tourbillon, which thanks to its unhurried pace, can be fully admired. Furthermore, the balance wheel beats at a leisurely 18,000 vibrations per hour, offering a slow moving spectacle.

The Benu Tourbillon features a stops-seconds flying tourbillon that completes one rotation in three minutes

One of the most striking elements of its movements is the ratchet wheel which is decorated with a traditional triple-band snailing to distinguish them from its peers. Ratchet wheel snailing is often taken for granted in watchmaking or may initially appear perplexing until one witnesses the machinery involved. This is because spinning an abrasive wheel against the ratchet wheel will only result in concentric circles, much like perlage. Achieving a radial pattern that emanates from the centre, however, requires the ratchet wheel itself to be constantly turning in the opposite direction. Thus, the process involves two spindles with one positioned at an offset radius for grinding and the other dedicated to turning the part. Once programmed, this can be executed reliably and quickly.

The distinctive triple-band sailing on the ratchet wheel. Image: Wanyu Lee (IG: Deletrium)

However, to achieve a stepped, three-dimensional effect, it took the brand several months to develop the right technique. The teeth of the ratchet wheel are initially bevelled and polished along the circumference, which contrasts well with the snailing. Starting from the innermost circumference, layers of snailing are progressively added outward.

The crown wheel has a black-polished steel cap while the ratchet wheel is decorated with their signature triple-band sailing. Note their finely polished teeth

The three-band snailing, in turn, contrasts nicely with the Glashütte ribbing which are widely spaced and typically feature four to six stripes on the movement. For a company that devotes so much effort into finishing its hands and movement parts, this is certainly not a cost-cutting measure but a deliberate aesthetic choice, as is the frosting on the base plate, so as to provide a subdued backdrop for all the decorated components. All the inscriptions on the two-third plate including the uppercase brand name are finely engraved by hand.

The inscriptions on the two-third plate are engraved by hand. Image: Wanyu Lee (IG: Deletrium)

Visible next to the ratchet wheel, the crown wheel is actually spokeless and is supported by a black polished steel cap that is held in place by two large screws. Black polishing involves meticulously smoothing its surface to the extent that it becomes a mirror, reflecting light as black. The edges of the cap are also bevelled and polished.

The two-third plate terminates with straight, bevelled edges and a large semi-circular cut-out that showcases the in-house balance wheel. The balance itself is finely executed with chamfered and polished rims while the arms are decorated with perlage. In the majority of movements, both the balance and escape wheels are held in place by cocks that have been hand-engraved with an exquisite floral pattern whereas the third cock that supports the pallet fork is snailed. There is virtually no component too small to receive a surface treatment; even the square head of the micrometer screw and the bevels on the edge of the head have been polished.

A Glashütte specialty, the cocks for the balance and escape wheels are engraved by hand while the bridge that supports the pallet fork is snailed (©Revolution)

It is this uniquely Saxon combination of qualities and dedication to detail, craftsmanship and technical quality that ultimately gives birth to watches that even after years and decades have passed will remain consistently compelling and undiminished by the tides of competition.