Daniel Roth

The Early Visionaries of Independent Watchmaking

Daniel Roth

The Early Visionaries of Independent Watchmaking

In 1985, two watchmakers and long-term Swiss residents, Danish-born Svend Andersen and Naples-born Vincent Calabrese, founded L’Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI), which united independent watchmakers and provided a promotional platform for their work.

Though not all independent watchmakers belong to AHCI, the association played a key role in perpetuating craftsmanship as a mark of prestige, becoming the launching pad for some of the most successful watchmakers we know today, many of whom have become brand eponyms.

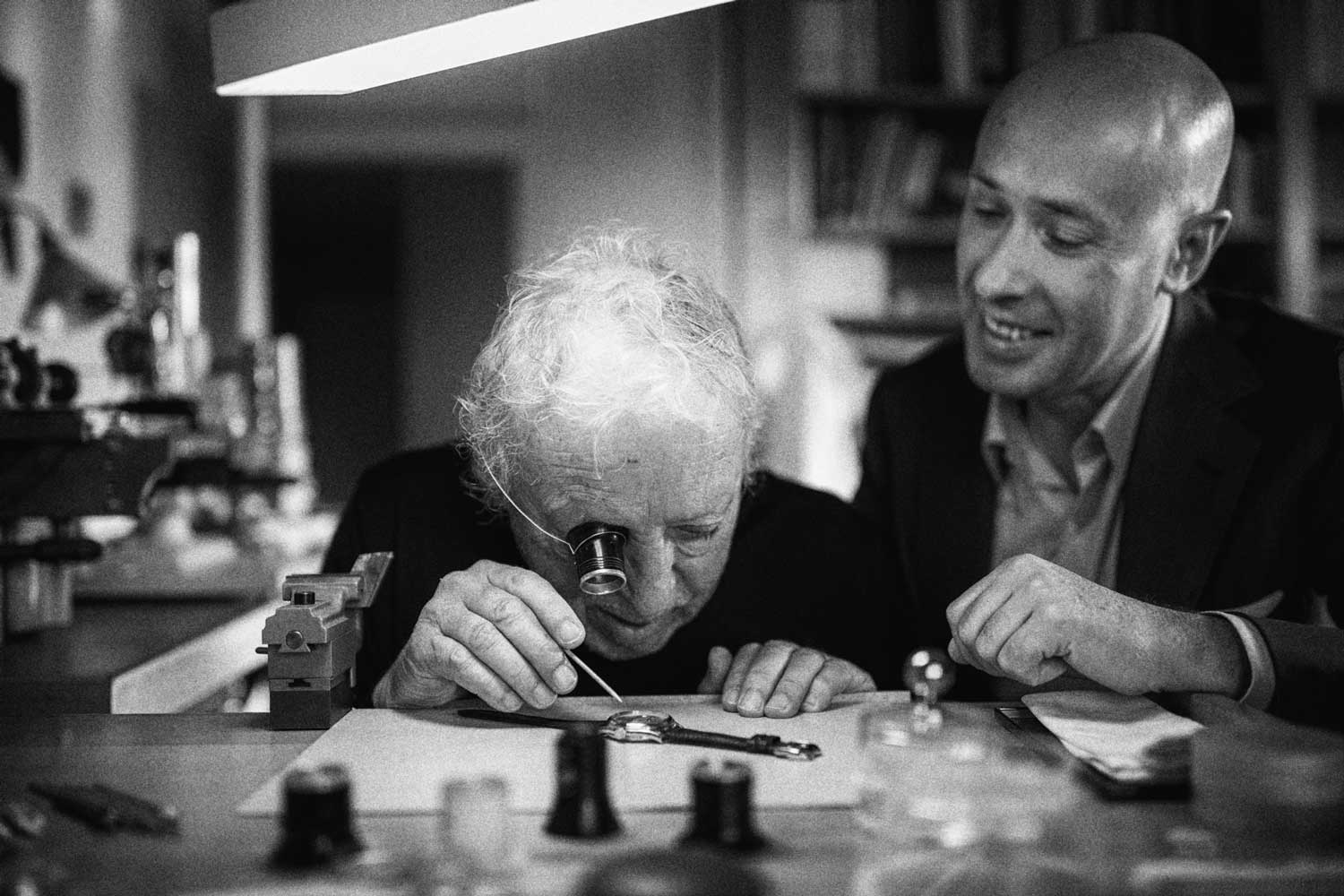

Danish-born Svend Andersen (left) and Naples-born Vincent Calabrese, founded the L’Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) in 1985.

Franck Muller — The Original Maverick

Franck Muller is largely responsible for spearheading the tourbillon boom that reached its height in the 1990s and 2000s

After almost a decade of making complicated watches privately, he founded his company in 1991 with the financial backing of Vartan Sirmakes, a watch case manufacturer whose clients included the likes of Patek Philippe and Daniel Roth. Muller certainly brought something new to the trade when many had stuck to the language and ideals set forth by Breguet. First presented in 1987 at an international watch exhibition in Italy, his Cintrée Curvex with its unconventional form — a large tonneau case that curved on three axes — and Art Deco numerals, hacked a path through the prevailing sea of watches that were considerably more sober in colour and design. It became a runaway bestseller of the ’90s, turning Franck Muller into a brand with a nine-figure turnover by the new millennium. A maverick in more ways than one, Muller was the pioneering celebrity watchmaker whose path to global fame has since been emulated by the likes of Richard Mille.

The Evolution 3-1 featuring the world's first triple-axis tourbillon

The Aeternitas Mega 4 with a total of 36 complications including a minute repeater, split seconds chronograph, a secular perpetual calendar and equation of time.

François-Paul Journe — A Horological Genius of Our Era

Journe’s work inimitably develops and builds upon the 18th- century inventions for modern wristwatches.

Like many a great watchmaker, Journe spent his formative years restoring vintage clocks and watches. Having been expelled from watchmaking school in Marseille, he took up an offer to work in his uncle’s restoration workshop in Paris and later resumed formal education at the L’Ecole d’Horlogerie de Paris. Upon graduation in 1976, he began working full-time for his uncle, during which he was exposed to the works of the great French watchmakers of the 18th century, including Le Roy, Janvier and Berthoud but most crucially Breguet, whose many inventions such as the tourbillon, the natural escapement and the principle of resonance would become paramount to understanding Journe’s later work.

Almost inevitably, through his books, pocket watches and common areas of interests, George Daniels became a great inspiration and a mentor to Journe. Both watchmakers were descended from the same spiritual lineage that began with Breguet. Both were driven by mechanical chronometry and precision and strove to emulate Breguet’s elegance in engineering.

Journe's most important watch to date, the Chronomètre à Résonance (Image: The Hour Glass)

The Chronomètre Optimum (Image: The Hour Glass)

Journe began his brand in 1999 with a set of 20 Souscription Tourbillons where each of his clients placed a deposit upfront, and from this, he gathered the capital to get his brand off the ground. The Tourbillon Souverain was the first serially produced wristwatch to feature a remontoir d’égalité, a constant force mechanism in the form of a blade spring that ensures a fixed amount of torque is released to the escapement each time.

The Souscription Tourbillon No. 10/20 (Image: The Hour Glass)

In such a clock, any error in rate in one pendulum tended to be cancelled out by the other, increasing precision. Breguet was one of the first watchmakers to have successfully achieved the phenomenon of resonance in a handful of his pocket watches, one of which was made for Britain’s King George IV (1762–1830), and one for France’s King Louis XVIII (1755–1824).

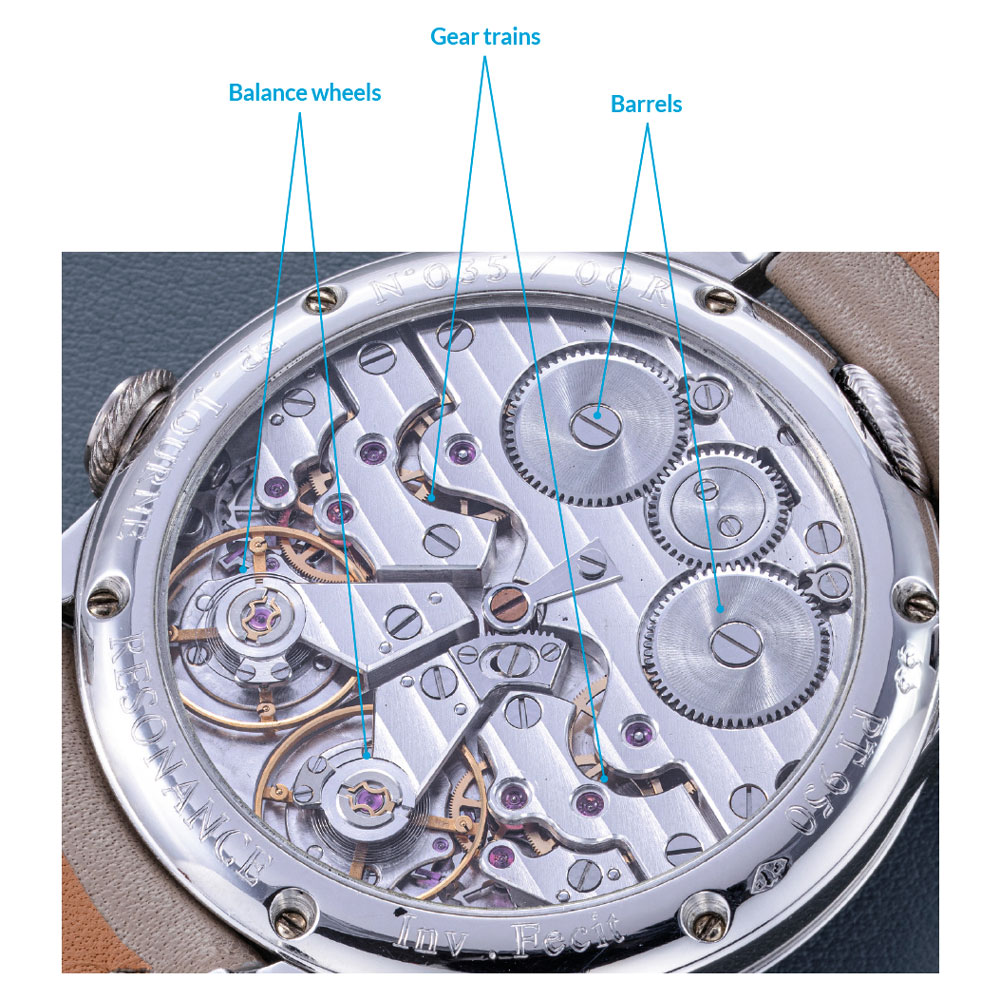

The movements in the Tourbillon Souverain and Chronomètre à Résonance (Images: The Hour Glass)

The movements in the Tourbillon Souverain and Chronomètre à Résonance (Images: The Hour Glass)

Additionally, the two balances must be adjusted so that their rates are as close to each other as possible, otherwise they can’t be synchronized. George Daniels also noted in his book, The Art of Breguet, that the balance wheels had to be free-sprung, as having a regulator with two pins reduces the effect of the vibration transmitted from the hairspring to the cock and main plate. The Chronomètre à Résonance was constructed based on these findings. It was the first of its kind in a wristwatch, and without a doubt, a feat of engineering.

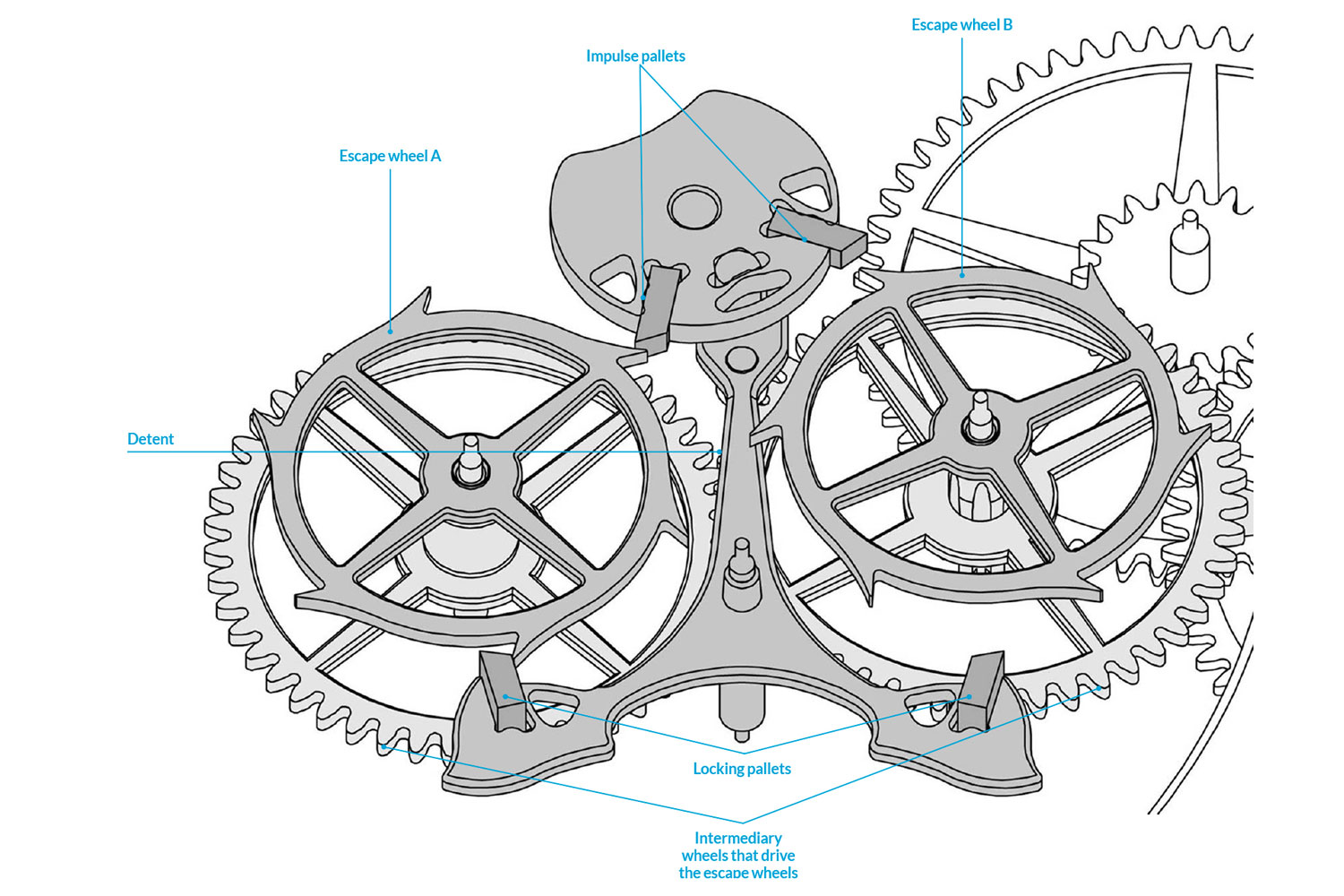

Like Daniels, Journe was also intrigued by the superior qualities of Breguet’s natural escapement and devised his version in 2012 in the Chronométre Optimum. In contrast to Breguet’s in which one escape wheel directly drives the other, the two escape wheels in Journe’s are attached to two respective intermediary wheels below that drive them. This setup also allows the escape wheels to have a more conventional design for locking and releasing the detent; Breguet had to design the escape wheels with a set of additional vertical teeth to do this.

Illustrating the bi-axial high-performance escapement in Journe's Chronomètre Optimum, in which the two escape wheels are driven by a second pair of wheels at the bottom

Journe’s technical genius is evident in many other aspects of the transmission system as well as other watches that are beyond the scope of this article. His distinctive style of design and engineering coupled with modern interpretations of these mechanisms of a bygone era have left a lasting mark on watchmaking and deservedly garnered him a cult-like following.

Vianney Halter — The Independent Trailblazer

Halter founded his own manufacture in 1994 and named it La Manufacture Janvier after the great Antide Janvier

In 1994, Halter founded his own manufacture, named after the great Antide Janvier (1751–1835). Like THA, La Manufacture Janvier was a subcontractor for various brands. While accumulating his know-how and experience in industrial production, Halter’s desire to create his own brand of watches only grew stronger.

When the Asian Financial Crisis hit in the ’90s, Halter took the time to develop his first watch together with Jeff Barnes, an American designer, leading to the initial brand name Halter-Barnes. In 1998, he presented the Antiqua at the Baselworld fair. It was an instantaneous perpetual calendar wristwatch that was revolutionary in its reverse- tech, steampunk design with four subdials, each within its own porthole framed with riveted bezels. Its asymmetrical case had an exceedingly complex construction consisting of 130 parts, including 104 rivets.

Beyond that, the Antiqua spared no expense in terms of its finishing, from the sharp, detailed hands to the white gold grained dial with hand engraved, lacquer- filled numerals to the contrasting brushed and polished surfaces of the case. The movement, on the other hand, was based on the twin-barrel Lemania 8810, heavily modified to incorporate a perpetual calendar module, two bridges that seamlessly hide its inner workings as well as an invisible rotor.

Halter presented the Antiqua at the Baselworld fair in 1998. It was an instantaneous perpetual calendar wristwatch that was revolutionary in its reverse- tech, steampunk design with four subdials (Image: Fred Merz)

In 2013, Halter unveiled the Deep Space Tourbillon, a watch that would take the idea of a multi-axis tourbillon to a new height. Till today, it remains one of the most visually impressive triple-axis tourbillon watches on the market. Under the dramatically domed crystal, the innermost cage of the tourbillon rotates on the first axis once a minute.

This carriage sits in a transversal structure that completes one revolution every six minutes, and the entire structure is in turn suspended in a blued titanium cradle that relies on a vertically positioned outer gear to complete one revolution in 30 minutes.

Halter unveiled the Deep Space Tourbillon in 2013, a watch that took the idea of a multi-axis tourbillon to a new height.(Image: Fred Merz)

Philippe Dufour — The Modern Master of Finishing

In 1978 Dufour set up his own workshop and began restoration work for five years before developing his first movement, a grande and petite sonnerie for a pocket watch

In 1978 he set up his own workshop and began restoration work for five years before developing his first movement, a grande and petite sonnerie for a pocket watch, which he supplied to the brand he had just departed from. But Dufour grew increasingly frustrated with having his name being passed over in silence as well as the attitude of brands — a sentiment echoed by François-Paul Journe years later. (On his decision to become an independent watchmaker, Journe famously proclaimed that he was “fed up giving pearls to swine”.)

In Dufour’s case, this would be rectified in what would become the world’s first grande and petite sonnerie wristwatch. After three years in the making, the wristwatch bearing his name was unveiled in 1992, the same year he joined the AHCI. This, along with a trip to Singapore where he found buyers through The Hour Glass, marked the launch of his eponymous brand.

A unique Philippe Dufour Grande Sonnerie in white gold with a clear sapphire dial showcasing the beautifully finished striking mechanism. (Image:The Hour Glass)

The differential splits the power from the mainspring and averages their errors to achieve a single averaged deviation for the time display. Thus, if one, for instance, beats at a rate of +3s and the other at −3s, the watch achieves a perfect 0. The two escapements in this approach are driven by a single gear train, which is not to be confused with a resonance watch in which two individual movements linked by a common mainplate achieves a single rate through the principle of resonance.

While the end goal is the same, the underlying methods cannot be more dissimilar. Whereas the resonance descended from a lineage that includes Breguet, Janvier and Christiaan Huygens, the differential setup used by Dufour is believed to have been pioneered by Ferdinand Berthoud (1727–1807). Dufour was inspired by a 1930s double regulator pocket watch produced by students at the watchmaking school in his hometown of Le Sentier.

Ultimately, having a differential is a more readily dependable method of achieving an averaged output as torsional resonance is inherently weak and can be influenced by many factors.

Beyond this performance-oriented mechanism, the Duality features a beautiful symmetrical construction that demonstrates an array of decorative techniques, including Geneva stripes, black polishing, hand-engraving and most of all, anglage. While the watch was initially planned for a series of 25 watches, Dufour only produced nine of them, and focused instead on the Simplicity.

The Simplicity with a grey dial (Image :The Hour Glass)

The impeccably finished movement of the watch with sharp inward and outward angles.(Image :The Hour Glass)

His superlative standards of finishing have been a great influence on new generations of watchmakers, from Rexhep Rexhepi, a promising young Kosovo-born watchmaker who shot to prominence with his acclaimed Chronomètre Contemporain watch, to as far afield as the Micro Artist Studio of Seiko Japan, whose Credor Eichi and Eichi II were heavily inspired by Dufour.

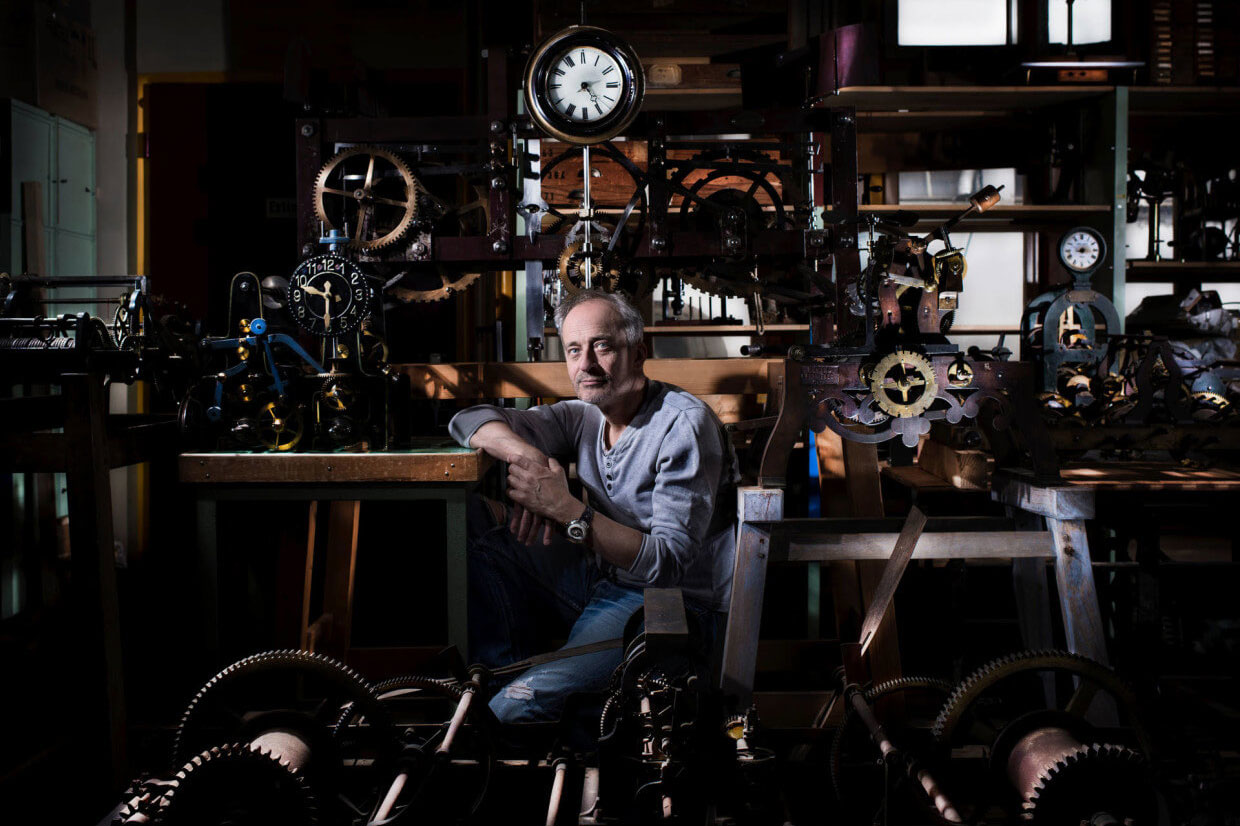

Daniel Roth — The Steadfast Horologist

Roth was amongst the earliest watchmakers to strike out on his own, establishing his eponymous brand in 1988, a decade earlier than many of his peers.

Roth was amongst the earliest watchmakers to strike out on his own, establishing his eponymous brand in 1988, a decade earlier than many of his peers. But his golden years were spent reviving Breguet. Having worked briefly at Jaeger-LeCoultre and subsequently Audemars Piguet, he was hired by François Bodet, the then director of Breguet, who had been tasked by the new owners, Jacques and Pierre Chaumet, to restore the brand to its former glory.

Roth’s work during the 14 years spent at Breguet beginning in 1973 would lay the groundwork for what modern Breguet is today. Much of it involved interpreting Breguet’s complications and design language in wristwatch form. From the engine-turned dials to the coin-edge case to the distinctive Breguet hands, these elements have become the hallmarks of the brand today.

Some iconic models launched during his tenure included the automatic perpetual calendar reference 3130, which was directly inspired by the Breguet No. 5 pocket watch as well as the tourbillon ref. 3350, which, with the tourbillon exposed at six o’clock, established the ultimate layout of the complication.

Roth’s work during the 14 years spent at Breguet beginning in 1973 laid the groundwork for what modern Breguet is today.

One of his most iconic models was the Double Face Tourbillon, which features a triple-armed seconds hand, where three blued steel hands of varying lengths sweep over three different seconds scales as the tourbillon rotates. Many of his watches, including his chronograph, perpetual calendar, tourbillon and minute repeater, were based on movements made by Nouvelle Lemania, which supplied movements to Breguet through his time with the brand.

But it wasn’t long after that Siber Hegner pulled the rug from under him, which led him to sell the majority of his shares to Singapore-based retailer The Hour Glass, who then sold them on to Bvlgari in 2000. This move led Roth to relinquish his remaining shares and bid goodbye to the company that bore his name a year later.

A Daniel Roth Double Face Tourbillon Limited Edition in steel (Image: The Hour Glass)

The Jean Daniel Nicolas Tourbillon 2 Minutes, handmade and finished by Roth (Image: A Collected Man)

The watch is designed, handmade and finished by Roth, demonstrating not just his technical prowess but also the traditional techniques and craftsmanship that are fast sinking into oblivion in the age of modern watchmaking. In fact, due to the labor-intensive nature of his work, he produces no more than two or three pieces a year.

Editor’s Note: A great way to learn more about these pioneering watchmakers in the field of independent watchmaking is through The Hour Glass’ The Persistence of Memory online exhibition.

The Hour Glass’ goal with The Persistence of Memory is to create a living online repository of the key members of this contemporary independent watchmaking movement, documenting its developmental timeline and photographing and archiving its most important watches.

Experience The Persistence of Memory here: https://ovr.thehourglass.com