Angelus

Dead Seconds Watches: Go Ahead and Jump

Angelus

Dead Seconds Watches: Go Ahead and Jump

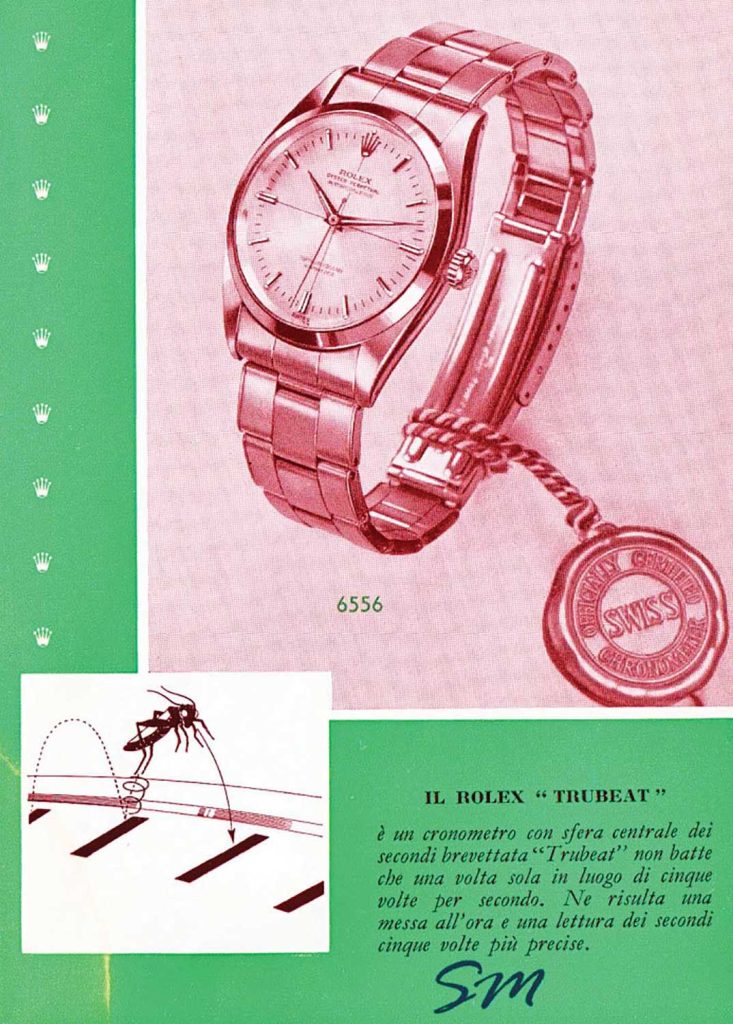

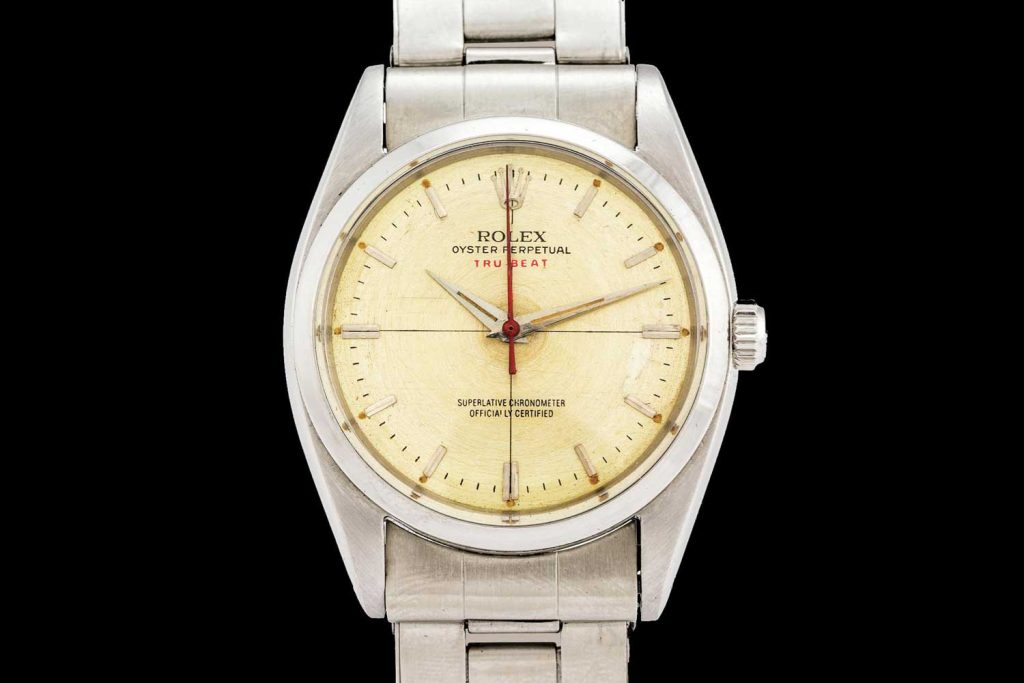

Without raising voice – or fist, as would have been justified – the salesman said it was purely mechanical. It was a Rolex Tru-Beat ref. 6556 and the salesman produced a genuine Rolex caseback opener to prove his point. Inside: the Calibre 1040 movement, unmolested and with the module producing jump seconds. The schmuck slunk out of the shop without a word, deservedly humiliated. I kept my schadenfreude in check, because we all make mistakes, but beating a dead horse, or in this case, dead seconds, is futile.

Call them what you will – Tru-Beat, True Seconds, jump seconds, seconde morte, sauterelle, dead seconds, dead beat, ad infinitum – the terms all describe the sort of watch that features a seconds hand that stops for one full second at each indicator, whether it is on a small seconds subdial or via a full sweep hand. I love the morbid whiff of “dead” just because the term “dead beat” is an old-fashioned term that also applies to idle or feckless individuals.

In a sense, that hapless, self-appointed “expert” can be forgiven for his hasty assessment because the feature describes only the seconds hand’s motion and not the type of movement that powers it. Conversely, not all quartz nor electronic watches feature dead seconds, which makes matters even more confusing. We are so used to the imperceptibly smooth sweep of a mechanical wristwatch’s seconds hand that it’s easy to forget how dead seconds were once a popular and desirable feature indicative of an ultra-precise timepiece’s added usefulness. If, that is, your life is monitored to the second – God forbid.

Rolex Truebeat advertisement

Like the traditional regulator dials that separate the hours and minutes to ensure rapid and precise timekeeping (especially worthwhile for watchmakers when setting the time), dead seconds add an element of exactitude, even if it lasts for a fleeting moment. By jumping from index to index and resting there for one full second – minus the brief, mere-hundredths-of-a-second interval during the jump – the precise pause is marked definitively.

Dead seconds escapements date back to 1675, and are credited to the astronomer Richard Towneley. English clockmaker George Graham employed dead seconds in his regulator clocks around 1715-1720, the addition of his name being a guarantee of the function’s credibility. By the second half of that century, and the emergence of direct-drive seconds to pocket watches, watchmakers including Romilly were able to devise timepieces that made one jump per second.

George Graham regulator clock with deadbeat escapement

As for the dead seconds’ technical requirements, this usually involves an addition to the gear train, and a number of variants exist. Typical would be a spring-loaded gear placed between the escapement and the seconds wheel; the gear loads up and releases at a steady interval based on the beat of the movement, calculated to match the beat of a watch, for example, if it beats five times per second, the gear will release every fifth beat.

Although this can be added as a module, “simple” it is not. Dealing with the storage and release of energy created by the power source is the basis of all mechanical watches. Interfering with it further adds to the complexity, so the watches on these pages are special indeed.

Despite the presence of this contemporary crop increasing awareness of dead seconds, it remains to be seen if they can dispel the notion that all watches with hands that jump from second-to-second are quartz. In which case, a dead seconds watch is worth having, if only for the joy of confusing others.

Angelus U10 Tourbillon Lumière

Chronograph collectors and Panerai fans know the name Angelus – one that seemed lost forever. Recently revived by La Joux-Perret, its debut model dispenses with any dependence on the past, as is the norm when reviving dead brands. Here, instead, “dead” describes the seconds.

Angelus U10 Tourbillon Lumière

But we’re here to address the segment on the left, displaying only hours, minutes and jump seconds. Look around the edges of the case, and there are windows to show off the movement. One neat feature is the power reserve, also positioned on the case’s side, with fuel gauge-style “F” and “E” indication.

U10 is a dazzler. Its ample stainless-steel case measures a wrist-filling 62.75 x 38 x 15mm, the innards viewed through seven sapphire crystals. Power comes from the manually wound Calibre A100 with 90-hour power reserve thanks to two barrels, with its dead beat seconds marked by a joyously cocky seconds hand. Alas, only 25 will be produced, at $99,950 each.

Arnold & Son TBTE Tourbillon

Although the reborn Arnold & Son has been around for a few years, it seems to have gone hyperactive of late, releasing a flood of exciting new models. Because the company is so cognizant of watchmaking history, it should be no surprise that it is one of the brands reviving dead beat seconds.

Arnold & Son TBTE Tourbillon

Its dead beat seconds are displayed by a large sweep hand, and the tourbillon is visible on the dial side, at the 6 o’clock position. Arnold, though, isn’t content merely to add jumping seconds without showing off the hardware: the dead beat seconds bridge is shaped “like a Celtic battle axe and the lever like an anchor”, the company expressly paying homage to Arnold’s maritime achievements.

TBTE’s 44mm round rose-gold case is fitted with the manual Calibre A&S5119. In addition to dead beat seconds and one-minute tourbillon, TBTE incorporates a remontoire to enhance precision. Like many watches at this level of complexity, the Arnold & Son TBTE is a limited edition, the 28 pieces retailing for $197,500.

De Bethune DB25T Tourbillon Watch

The DB25 family is described by the company as “its classic watch for any occasion”. One look at this beauty and you can see 500 years’ worth of horological genius distilled into a creation fitted into a 44mm white- or pink-gold case.

De Bethune DB25T Tourbillon Watch

Oozing 18th-century horological classicism, the dial of the DB25T is a star-studded sky in blued mirror-polished titanium, inlaid with white gold stars, with grained and engraved sterling silver hours and minutes chapter rings, traversed by slim hands in polished steel with Breguet-style ends for the hours and minutes. De Bethune also employs the jumping seconds feature in its DB25 Zodiac models.

Completed with an alligator-leather strap with pin buckle, the DB25T is offered in a limited edition of 20 pieces. For this one, price is on application.

DeWitt Academia Out of Time

By now, everyone knows that Jêrome de Witt is a direct descendant of Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte, which is a rather neat selling point if one adores history. As the company unabashedly revels in its aristocratic roots, it is no surprise that the watches celebrate classicism. Having met JdW a few times, I know that he’s a certifiable watch fanatic. Academia Out Of Time, though, seems almost minimalist compared to the company’s more outré offerings.

DeWitt Academia Out of Time

What the two subdials give you is the best of both (seconds) worlds: according to DeWitt, Out of Time’s dead beat hand “serves as both a regulator and an indicator of the seconds function in the display at 4 o’clock”. The other is “a free seconds hand, a DeWitt invention. These two functions represent the opposition between real time, in the form of regulator function of the dead beat seconds hand that momentarily halts at each second, and virtual time, freely following its wild and endless course.”

A wordy way of saying you get sweep and jumping seconds in one watch, but it’s nice not to have to choose. Price on application.

F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain Seconds

Of the various classicists among the new wave auteurs, François-Paul Journe is one of the most celebrated. Like Michel Parmigiani, he has immersed himself in the history of horology and has revitalized a number of venerable complications. His showcase for dead beat seconds is the Tourbillon Souverain Seconds, a watch that looks like it could have stepped out of Breguet’s atelier.

F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain Seconds

Here, the main dial in the 40mm case – offered in a variety of metals and dial colours and with strap or bracelet – carries the hours and minutes display as a single subdial at 2 o’clock, while opposite is the oversized tourbillon at 9 o’clock. Between them is a small subdial for seconds, the dead beat seconds element enjoying its own piece of real estate. A power reserve marking the manually wound, rose-gold Calibre 1403’s 42-hour duration resides at the 12 o’clock position, shown with a retrograde hand. Price on application.

Grönefeld One Hertz

“That’s it, baby, when you’ve got it, flaunt it!” shouts Max Bialystock in The Producers, which is exactly what Bart and Tim Grönefeld’s One Hertz does with its dead beat seconds display. In the manner of Jaquet Droz, the One Hertz provides a separate, larger dial dominating the main dial for the seconds hand, with hours and minutes on a subdial at 2 o’clock and power reserve at 11 to mark the 72-hour duration. The other indicator is a Grönefeld specialty: a hand at 3 o’clock indicates whether the crown is in winding or setting mode via an arc marked “W” and “S”.

Grönefeld One Hertz

A glimpse through the caseback of this 43mm watch reveals a handsome movement indeed, featuring hand-finished, stainless steel bridges with recessed micro-blasted surfaces and raised borders, the finishing truly exquisite. Prices are €60,000 in titanium and €73,500 in red gold.

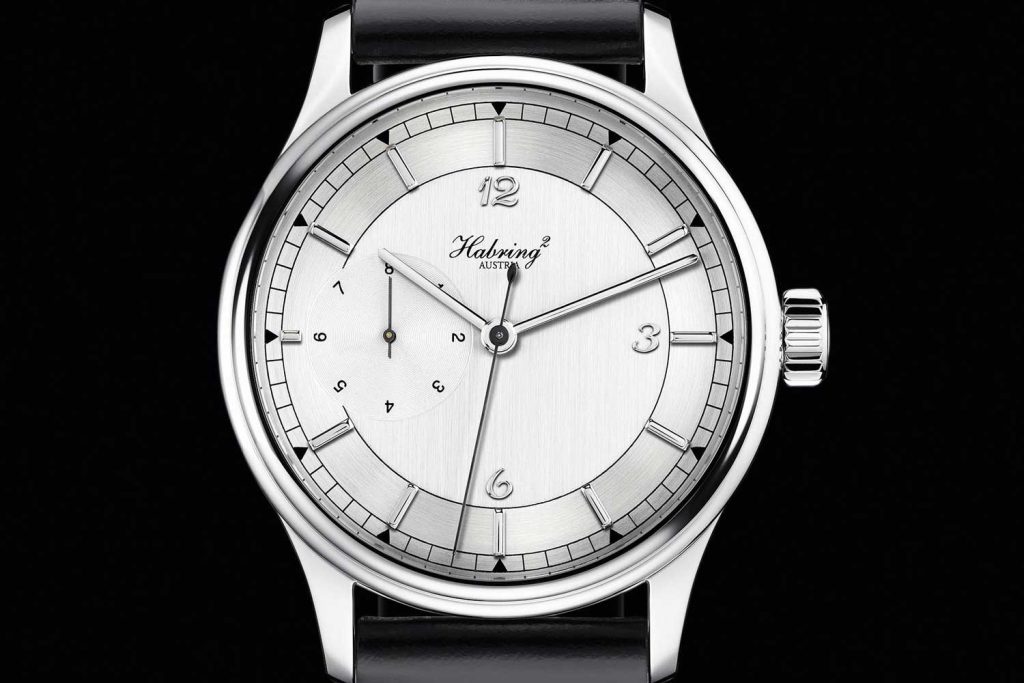

Habring2 Foudroyante

Ah! For a change, a dead beat seconds watch with automatic winding, and one based on the gear train of a familiar and dependable workhorse: ETA’s Valgranges A07 movement with roots in the 7750. Located in Austria, Habring2 produces less than 200 watches per year, but with a catalogue of eight or so models, that means a maximum of a dozen per model per annum.

Habring2 Foudroyante

At first, if you only see a photo of the 42mm Foudroyante, you might wonder what a subdial with eight divisions might time – maybe power reserve? But see it in action, and you’ll find that the “flashing seconds” hand displays the second in eighths, traversing the dial once per second. With this watch, you get not one but two jumping hands. It is also worth noting that Habring2 offers a dead beat movement in other models.

Fully wound, the Foudroyante runs for around 45 hours. Available in stainless steel, titanium or gold, prices start around €5,000, so this is one of the more approachable dead beat seconds watches on the market today.

Jaeger-LeCoultre True Second

Last year, when Jaeger-LeCoultre re-issued the handsome Geophysic, the company must have delighted in the mini-controversies stirred up among enthusiasts by having three versions: one a near-exact aesthetic replica and two slightly modernised. Regardless, the response was overwhelmingly positive, so the line has gone beyond the tribute stage to qualifying as a complete direction in the catalogue. But who would have expected the second batch to include a dead beat seconds model?

Jaeger-LeCoultre True Second

With robust 39.6mm case, date at 3 o’clock, and power reserve of 40 hours, the Geophysic True Second is a sublime solution for those who want a marriage of a classical wristwatch and a unique feature that addresses the need for the precision that inspired the original back in 1958. The True Second is priced at £6,400 in steel, and £12,800 in pink gold – genuine bargains by any measure.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Morte

While Jaquet Droz is not the only brand to issue regulator-look watches, it has a lock on the style: say “Jaquet Droz” to anyone familiar with the line, and the company’s figure-of-eight layouts will be pictured instantaneously. This practice of separating the various displays into subdials begged to be applied to jump seconds.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Morte

Fitted with Jaquet Droz’s new automatic Calibre 2695SMR, the model is the first to house it; the company says the calibre will be used in future offerings, so one might assume that dead seconds will become a regular feature. It employs a balance spring made of silicon, among other novel details, while the movement’s designers fitted a 10-toothed cam rather than the 30-tooth cam typical of a dead beat train.

Limited to 88 pieces, the Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Morte is priced at a reasonable SFr.29,000 plus local taxes.

Leroy Osmior Chronomètre à Tourbillon

This brand has oodles of admirable provenance, a history that ranks with the most revered, but it’s almost too-well-kept a secret. For the dead beat seconds aficionados among you, take note that the Leroy Osmior Chronomètre à Tourbillon follows the discreet route with a simple but magnificently detailed Grand Feu enamel dial hiding an abundance of horological riches.

Leroy Osmior Chronomètre à Tourbillon

But the Leroy Osmior Chronomètre à Tourbillon has something else I don’t believe can be found in any other dead seconds watch: a chain and fusée movement. One of the rarest calibre types to be found in wristwatches, this adds a whiff of history to the visuals when you flip open the hinged back of the 41mm case to observe the astonishingly complex manufacture movement. If that isn’t enough, this dead beat also boasts a direct-impulse constant force escapement and chronometer rating certificate direct from the observatory at Besançon.

Its price is on application, the watch’s rarity assured. Feeling of possessing elevated taste: guaranteed.

Patek Philippe ref. 5275P

Patek Philippe’s 175th Anniversary yielded so many riches that some of them might have been missed in the frenzy. This treasure, though, will outlast most because it offers a unique (at least, to this scribe) combination of functions. Not only does it join the present company by virtue of jumping seconds, it also features a digital jumping hour, jumping minutes and chimes – or, as the company charmingly described the latter, “an acoustic indication at the top of every hour”.

Patek Philippe ref. 5275P

Bearing the inscription “PATEK PHILIPPE 1839 – 2014” on its caseback and limited to 175 pieces, ref. 5275’s price is on application. Nice way to celebrate, eh?

Rolex Tru-Beat

If vintage is your thing, Rolex’s Tru-Beat is the definitive dead seconds wristwatch of yore. Unless you’re lucky enough to own the rare Doxa jumping seconds watch with Chezard Cal. 2-115 dead beat movement, a Candino Sprint or the rumored dead seconds watch from the West End Watch Co., this is the only game in town. But also one of the best.

Rolex Tru-Beat

But that is probably a bubbe meise, and I’ve heard of greater transgressions. Rarity aside, the Tru-Beat was produced from 1954-1959, probably targeting professionals such as doctors. Find one now in proper working order and you can expect to hand over £10,000. But wouldn’t it be grand if Rolex brought it back?