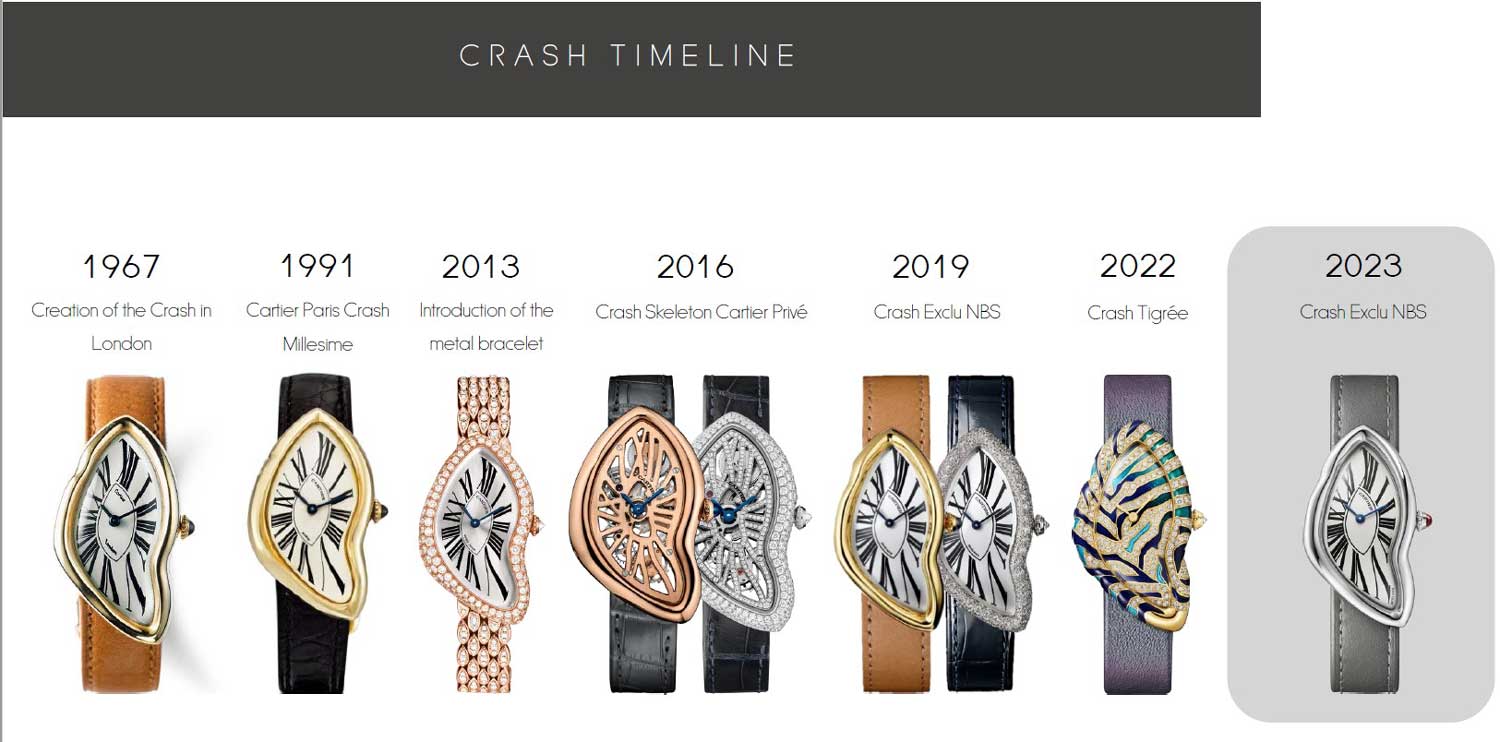

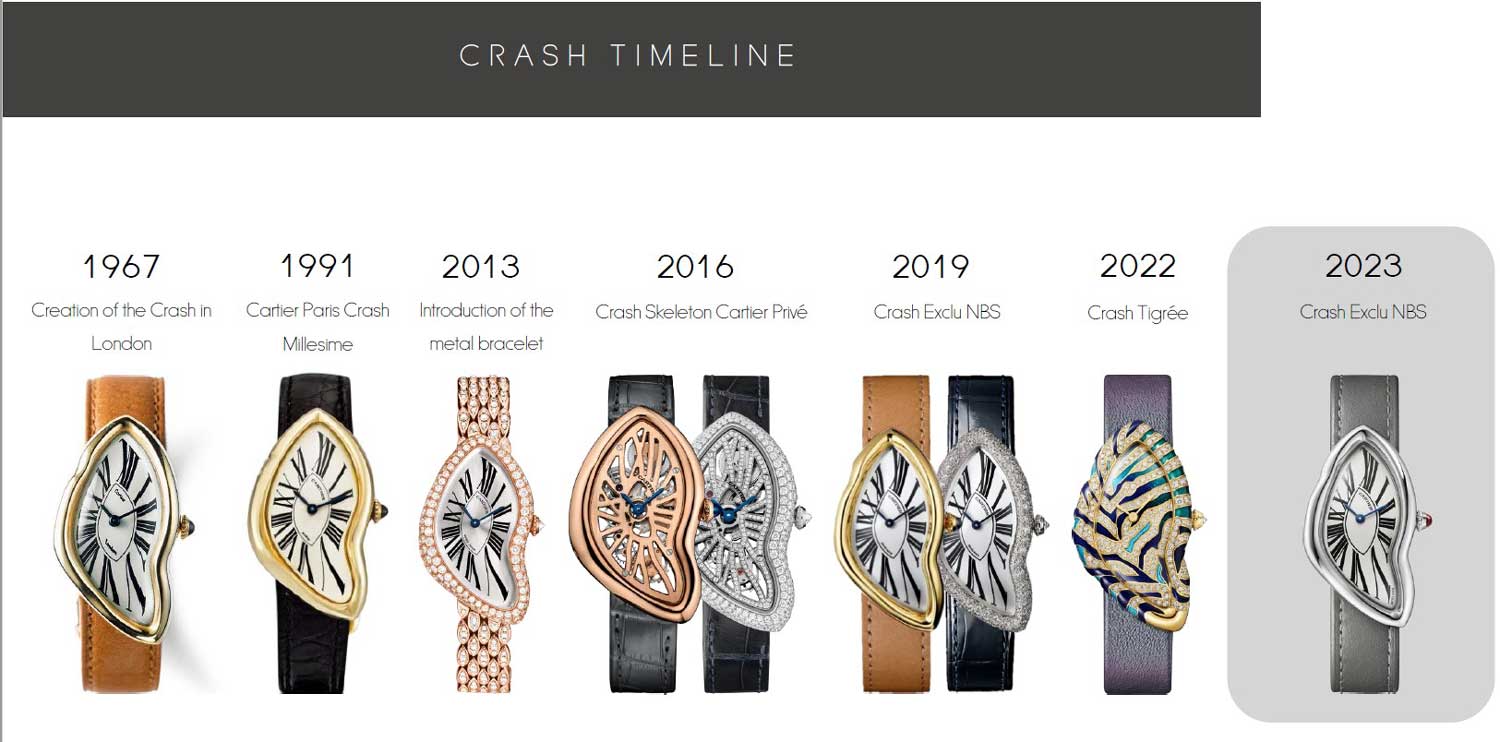

As the Crash becomes one of the most collectible watches on the planet today, we dissect its historical significance, explore its myriad iterations and chart its price performance over time.

Among all the distinctively shaped watches produced by Cartier throughout its history – the Tank, the Santos, the Tonneau, the Cintrée – nothing quite compares to the Crash. Even amidst its asymmetrical peers – the Tank Asymétrique, the Cloche, the Baignoire S – it is the most artistically unfettered, seemingly devoid of any mathematical definition – a fantastically abstract silhouette that sits astride the fine line between grace and aggression.

It is a watch whose appeal is as rooted in the sophistication of its design and the urban legend of its origin – purportedly moulded by a fatal car crash – as it is in what it represented for a dyed-in-the-wool, traditional luxury house like Cartier. It remains a vivid relic of Cartier London in the Swinging Sixties, a mythical hub with a creativity that was uniquely conditioned by the city it called home. More broadly, the Crash also serves as a reminder of a time in Cartier’s history when the production of watches was an artisanal affair. With the march of time, these strands have been deeply woven into the identity of the Crash, elevating it to one of the most coveted watches on the planet.

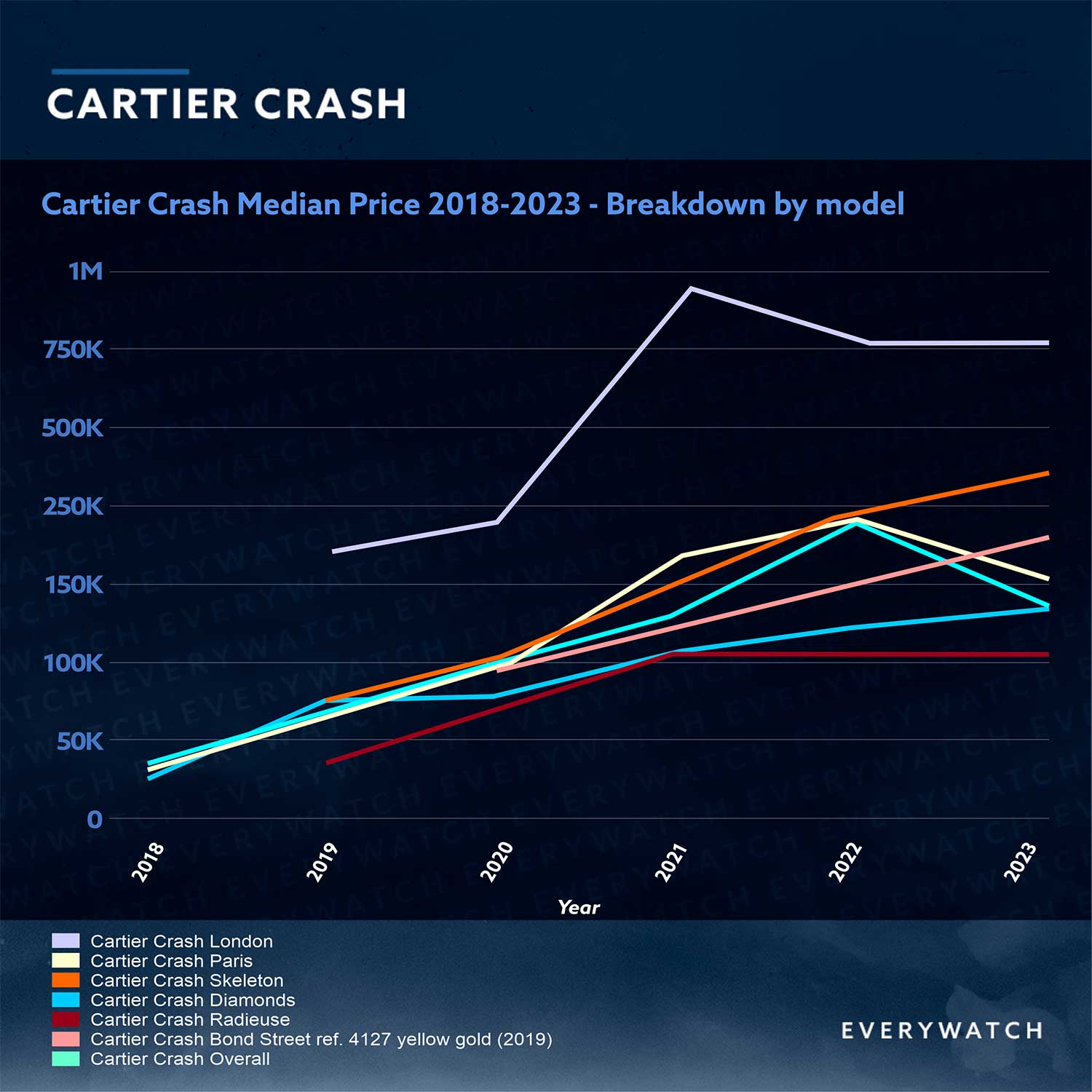

Today, we delve into the fascinating context in which the Crash emerged, explore its variations from the original production run in London to the present day, and the nuances that have shaped their price trends over time. We would like to extend our gratitude to the

EveryWatch team for generating the graphs and charts used in this report. Their platform, which draws data from a vast database comprising over 250 auction houses and 150 marketplaces globally, has proven to be an indispensable resource.

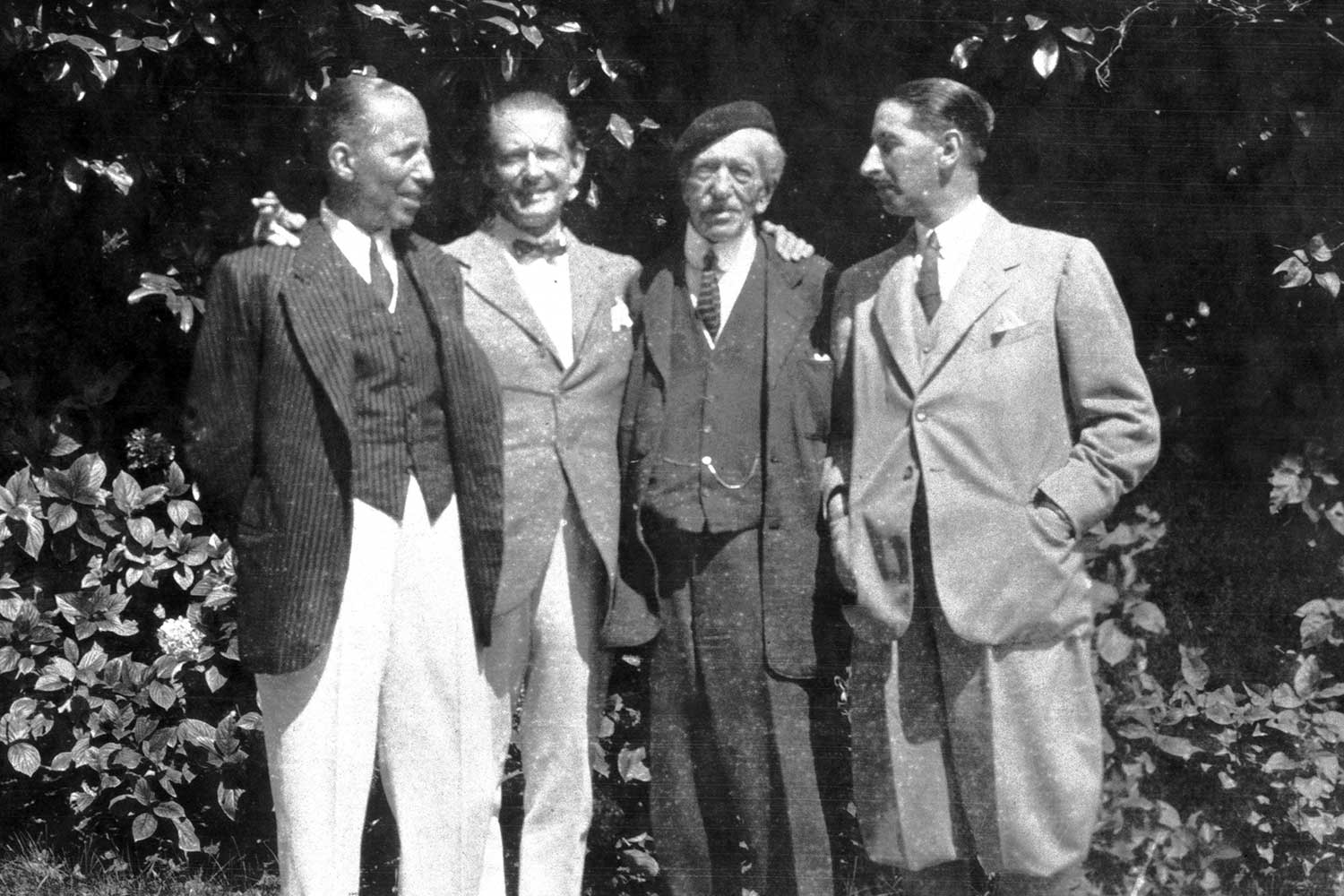

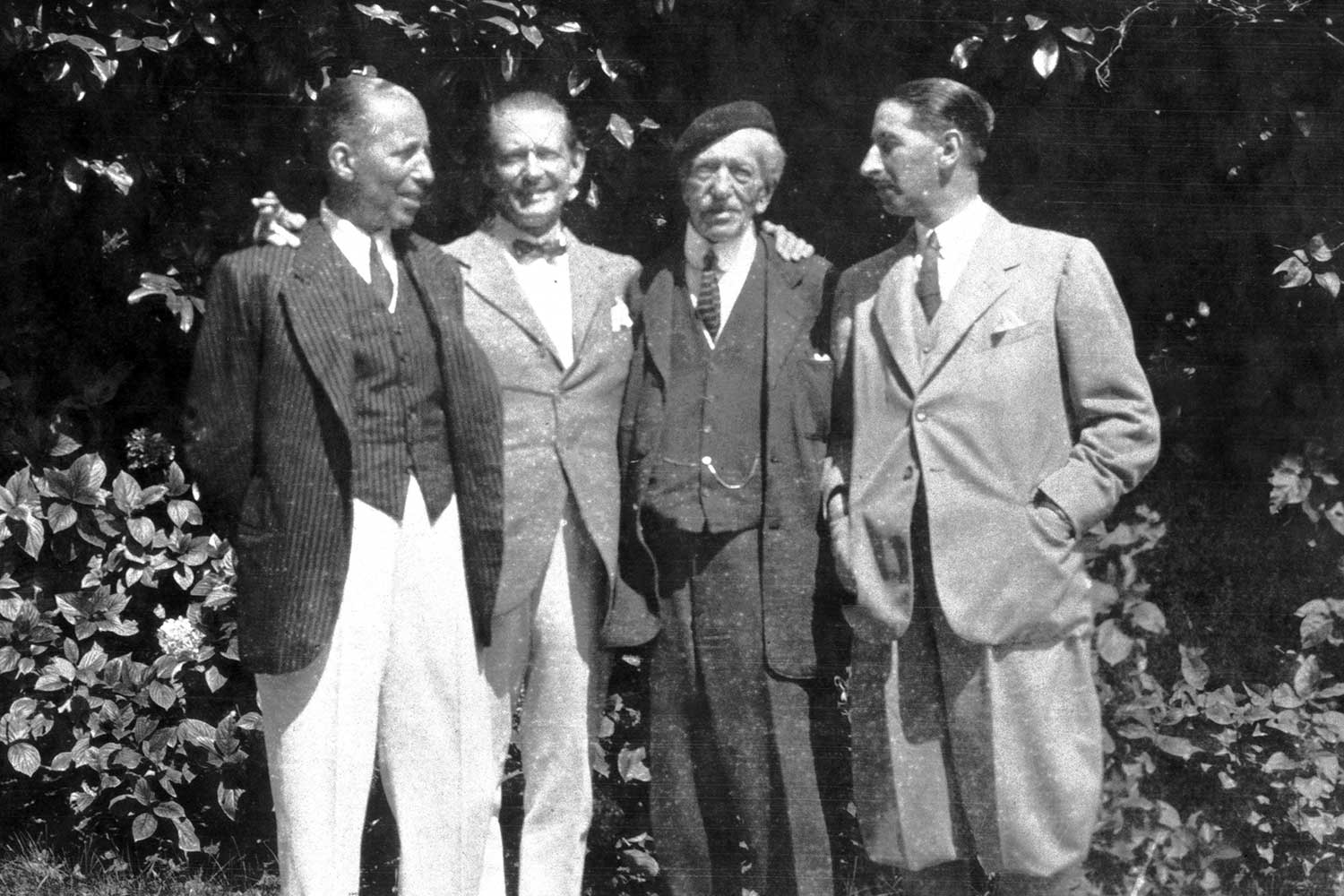

It was in 1902 when the maison founded in Paris in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier extended its reach to London. Alfred, the son of Louis-Francois Cartier, along with his three sons – Louis, Pierre and Jacques – had hatched a plan for global domination. Their foresight, predating the ease of modern travel, aimed to position Cartier as the jeweller of choice for royalty and the world’s elite, regardless of their geographical location. Louis oversaw the Paris headquarters, while Pierre headed the subsidiary in New York, and Jacques, initially accompanied by his older brother Pierre in London, took charge of affairs in the English capital.

Alfred Cartier and his three sons in 1922. From left: Pierre, Louis, Alfred and Jacques. (Image: Cartier)

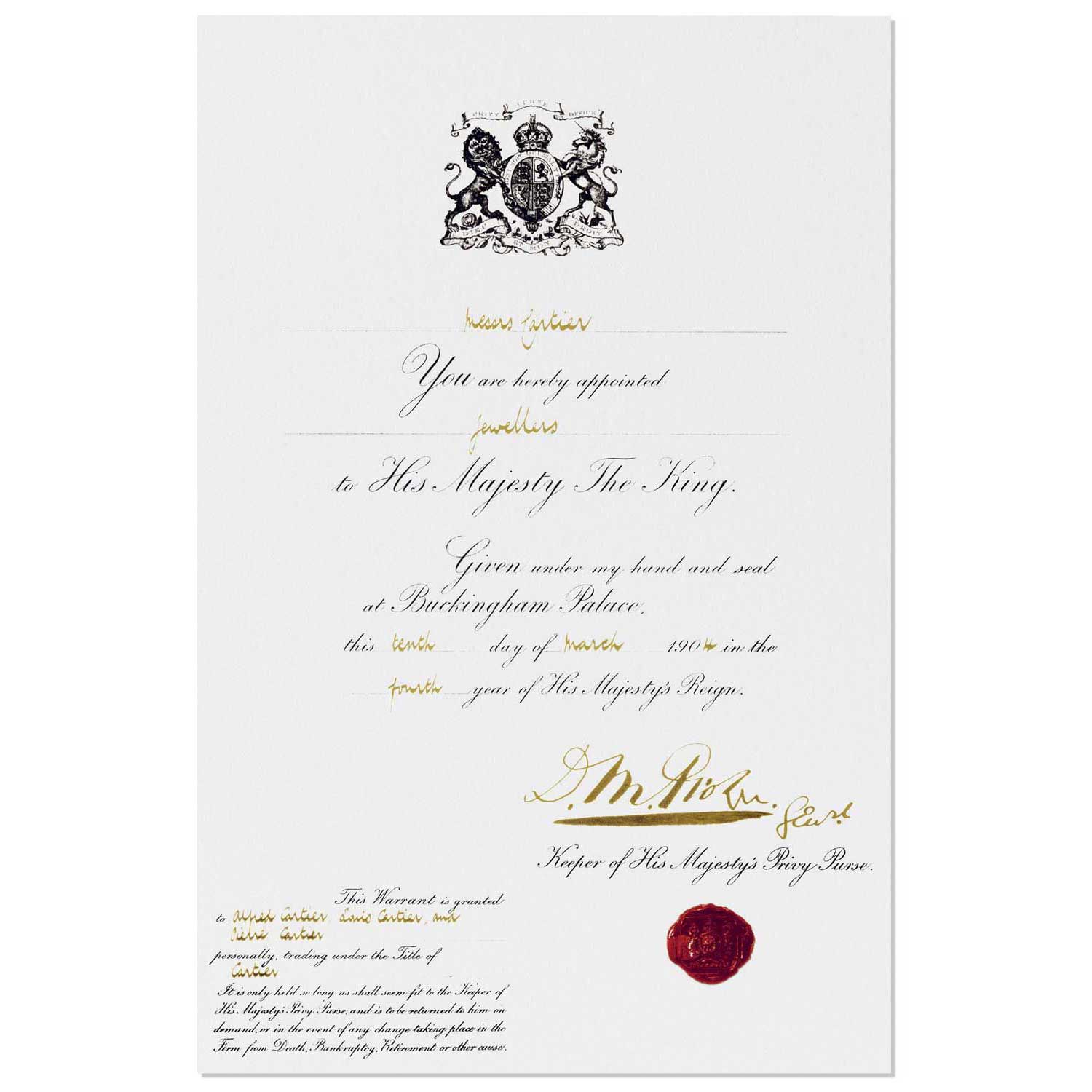

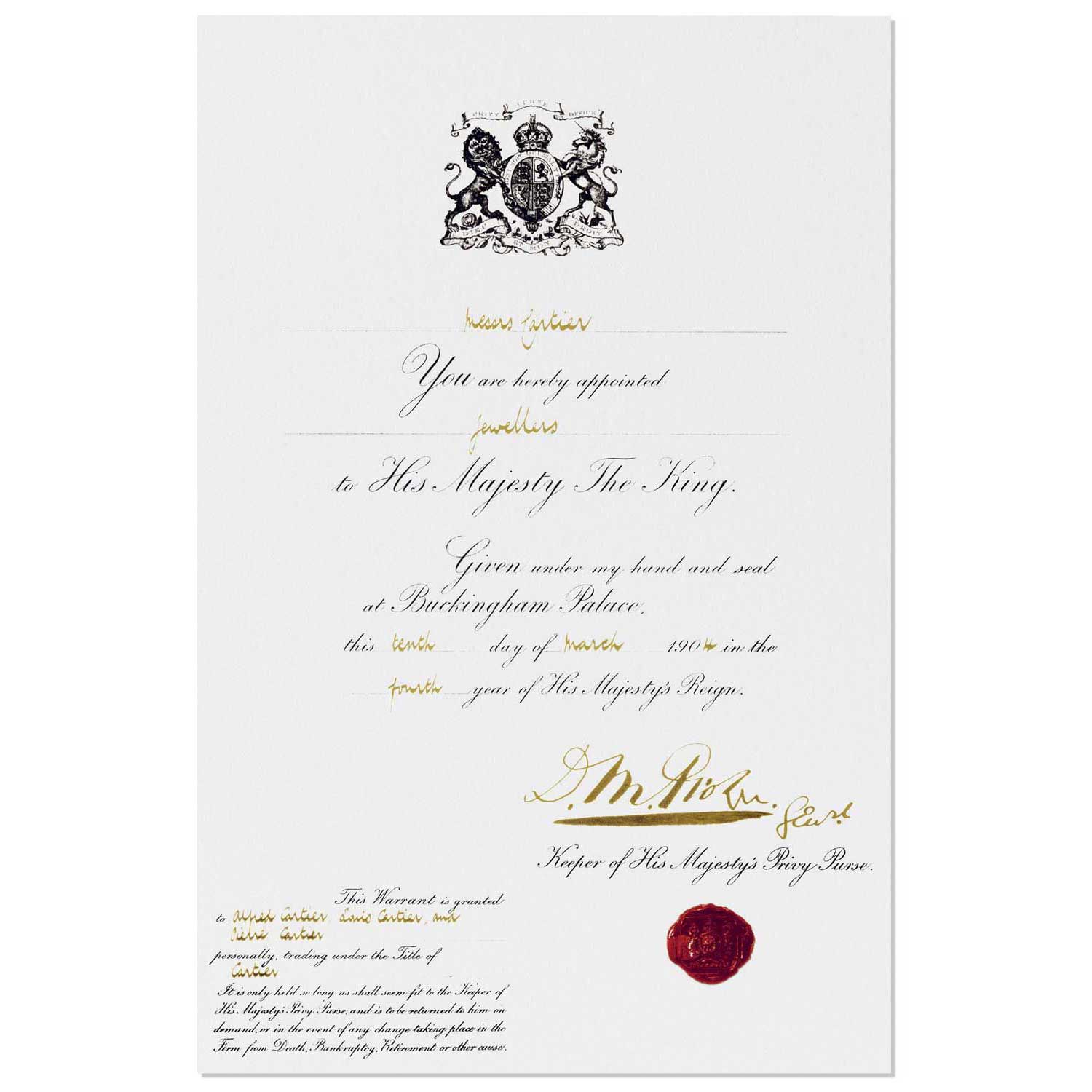

Pierre shared a special bond with the Royal court as the Prince of Wales, who would later become King Edward VII, had been a loyal patron of Cartier on rue de la Paix in Paris. He affectionately dubbed it “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers.” However, following the passing of his mother, Queen Victoria, in 1901, royal protocol prevented him from making the cross-channel shopping trips he had once enjoyed. He placed an order for 27 tiaras for his coronation, which Cartier could now fulfil more conveniently at the new London outpost, and issued a Royal Warrant of appointment to the jeweller.

Just two years after setting up shop in London, Cartier would receive a Royal Warrant from King Edward VII on March 10th, 1904. King Edward would famously call Cartier the "jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers". (image: Cartier)

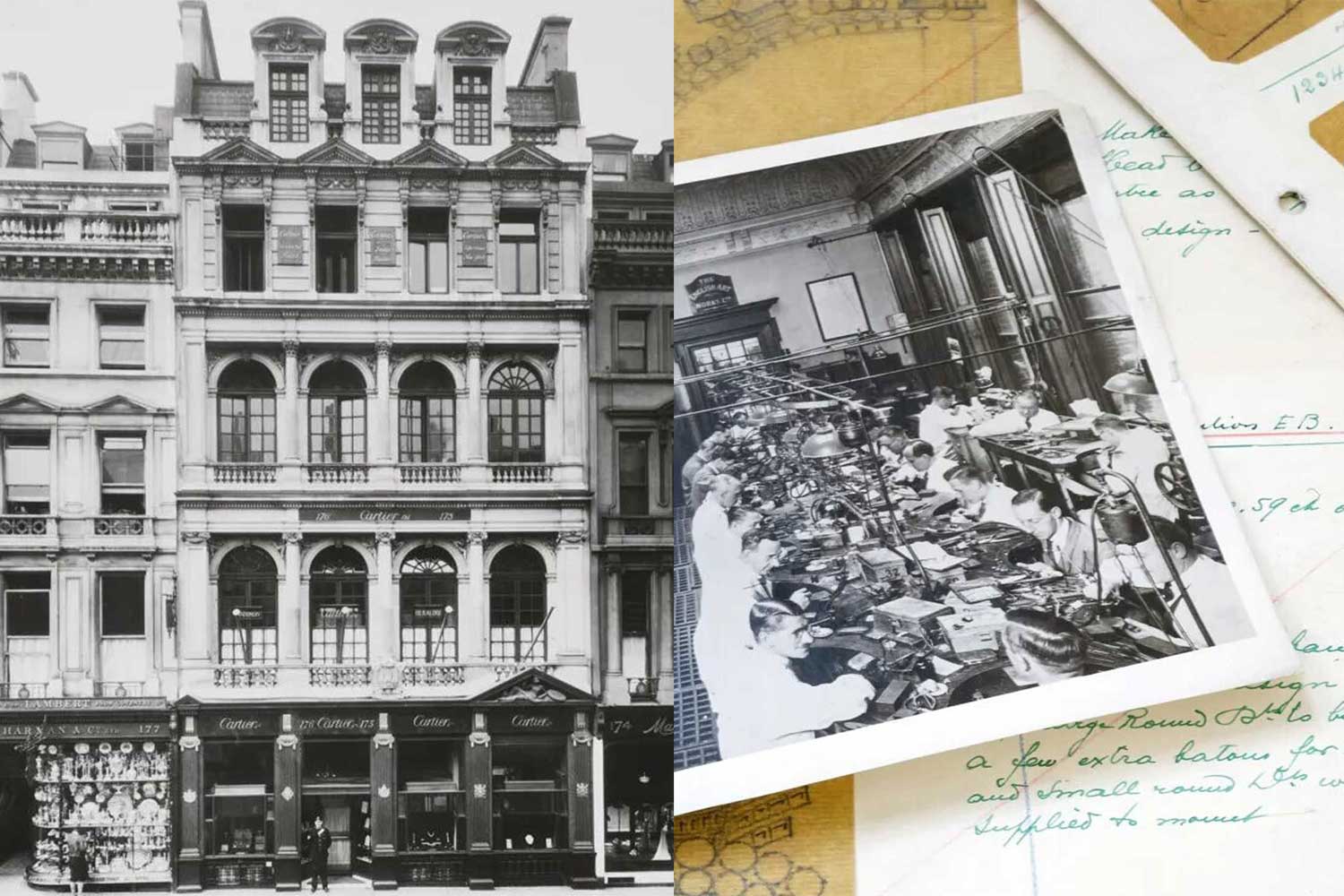

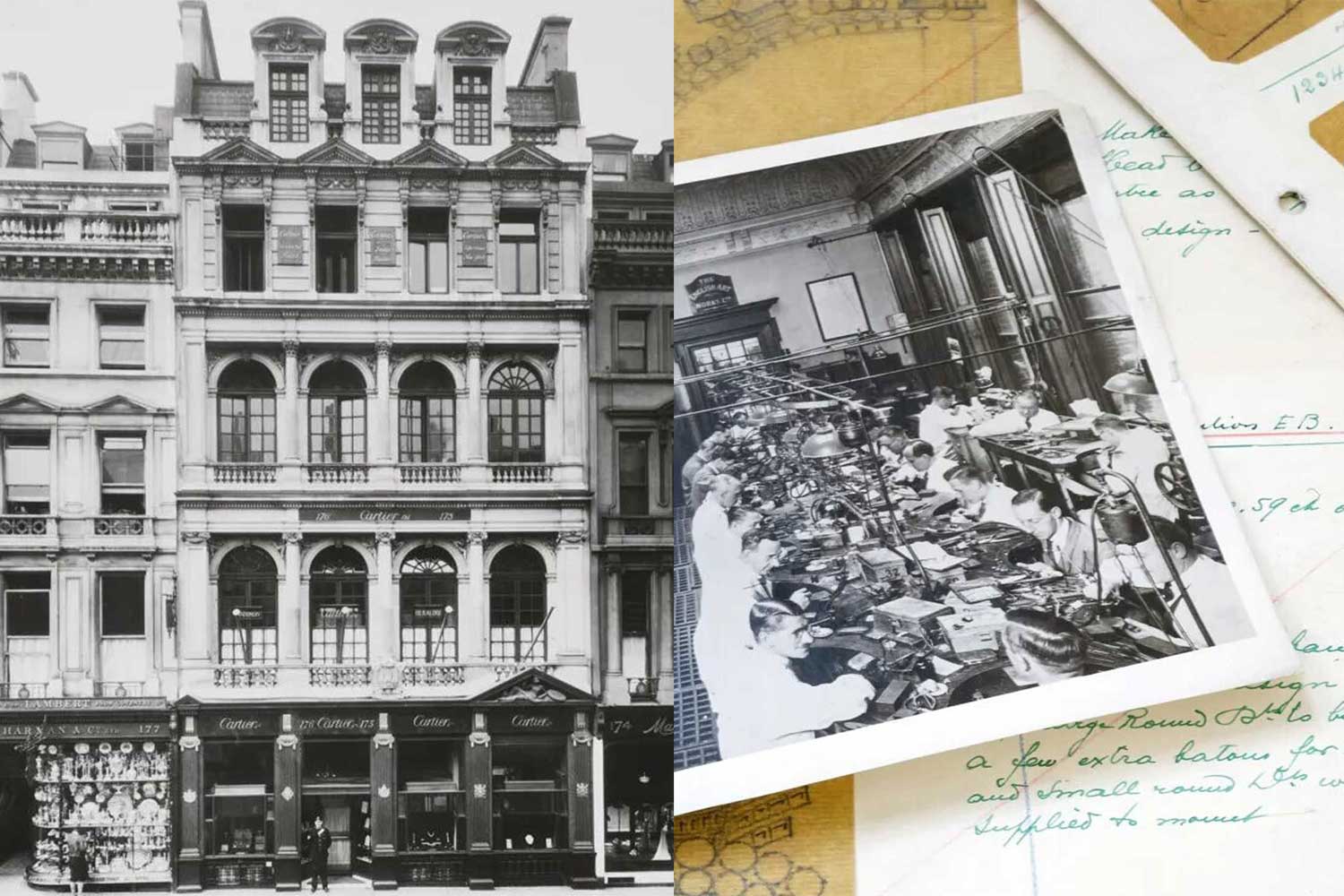

Jacques would eventually move the store from 4 New Burlington Street to its present location at 175-177 New Bond Street in 1909, just a few years after his older brother Louis in Paris had designed the Santos Dumont watch for his aviator friend Alberto Santos-Dumont. Most intriguingly, the new storefront boasting five storeys was more than just a retail space; it was a full-fledged workshop with the ability to conceive and produce its creations independently. Jacques had established the English Art Works workshop in 1921, putting together a workforce made up of local goldsmiths, jewellers, and various skilled artisans. Cartier relied on the senior craftsmen to train the younger generation, with each initiate beginning their journey as an apprentice, enduring a rigorous six-year training period before assuming their roles as full-time employees.

Left to right: Cartier London flagship at 175-176 Bond Street in the early 1900s before it acquired No. 177 on its left; The English Artworks workshop seen here in 1930 was the engine that produced watch and jewelry works of art for Cartier London. (images: Cartier)

Adding to the historical significance of the boutique, during the Second World War, after an unsuccessful attempt to secure protected status for its jewellery craftsmen, the workshop underwent a dramatic transformation, pivoting from its customary craft of fashioning maharajas’ necklaces and coronation tiaras to the production and repair of military instruments such as gauges and compasses. At one point, it even became the office of General Charles de Gaulle who had sought refuge in London to evade Nazi-occupied France.

Post-war London in the 1950s was characterized by restraint, with echoes of wartime rationing and conservative social norms. However, as the 1960s came into view, a seismic cultural shift began to shake things up. This was the era of the Swinging Sixties, where a dynamic youth culture, economic prosperity, and a thirst for personal freedom converged to create an unforgettable wave of change in the heart of London. By that time, Jean-Jacques, the son of Jacques Cartier, had completed an apprenticeship in the Paris branch under Charles Jacqueau, Cartier’s top designer. Jean-Jacques took charge of the London operations and focused on expanding its watch offerings. Among the three branches, Cartier London holds such mystique as it took on a life of its own, mirroring the city’s intricate tapestry of cultural, social, and artistic transformations. The Baignoire Allongèe, the Pebble and the Asymétrique all emerged from the London boutique. But its most striking creation was the Crash in 1967.

Until recently, the genesis of the Crash was shrouded in mystery. The lack of official records gave rise to many bewitching tales. Some believed its design was inspired by the melting clocks in Salvador Dali’s surrealist masterpiece, “The Persistence of Memory” while a more widely circulated narrative was that it was born from a Cartier Maxi Oval (Baignoire Allongée), which underwent dramatic distortion in the scorching aftermath of a car crash.

The truth was more sober but nevertheless fascinating. According to Francesca Cartier Brickell, the granddaughter of Jean-Jacques Cartier and the author of The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire, was that the Maxi Oval indeed served as a jumping off point. But in hopes of capturing the spirit of the psychedelic era, Jean-Jacques and designer Rupert Emmerson pushed the boundaries of Cartier’s visual identity in ways that were so utterly out of step with anything Cartier had ever done before.

Francesca Cartier Brickell, granddaughter of Jean-Jacques Cartier tells the comprehensive story of her family in her book - The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewelry Empire

Cartier Brickell wrote, “The reality was that the 1960s were a time of nonconform-ism in London. Several loyal clients, including the actor Stewart Granger, had been demanding a watch “unlike any other.” Jean-Jacques, who worked closely with the designer Rupert Emmerson on watches and cases, discussed with him how they might try adjusting the popular Maxi Oval design to look as though it had been in a crash “by pinching the ends at a point and putting a kink in the middle.”

Interestingly, Emmerson pitched various versions of the proposed concept to Jean-Jacques at their following meeting. He even included one design featuring a dial with a cracked appearance to emphasize the crash theme, although this suggestion was too much for Jean-Jacques. While he was open to innovation, Jean-Jacques believed that the end product should remain an aesthetically pleasing object. Therefore, Emmerson was advised to dial back some aspects of the design, leading to the abandonment of the cracked dial idea.

After finalising the design, they sought advice from Jaeger-LeCoultre to determine the most suitable movement. The case was entrusted to the craftsmen at the Wright & Davies workshop in East London where gold sheets were manipulated by hand into the asymmetrical case – there was no mould. It was subsequently finished by hand by jewellers. Cartier Brickell notes that crafting a standard watch case typically required thirty-five hours of labor, but this unique creation, with its unconventional curves, marked a significant departure from the typical rectangular, square, and oval models, demanding a considerably longer production timeline. The dial, on the other hand, was painted by hand by Rupert Emmerson.

Once they were completed, they were forwarded to Cartier London’s head watchmaker, Eric Denton. During the assembly process, they came to realise that designing the dial was a more high-wire act than that. As the gears that make up every mechanical watch are by nature circular and the hands are straight, it was a significant challenge to accurately position the distorted Roman numerals on the irregular dial for accurate time reading.

As a result, they had to take the watch apart and repaint the dial multiple times. Cartier Brickell wrote, “ For all the enormous work involved, the Crash watches did not make the firm huge profits. The first one was sold for around $1,000 (approximately $7,500 today).” Due to the artisanal nature of the Crash, it was never produced in large numbers.

By the time the Crash was born, Claude Cartier, the son of Louis had already sold the New York branch, with Marion Cartier Claude, the daughter of Pierre selling the Paris business a year later in 1968, making London the last of the three Cartier boutiques that was still being run by a family member until 1974.

London Crash (1967 to 1990s)

The London Crash of 1967

The initial Crash watch stood out not just for its distinctive design but also its bold dimensions. Produced in yellow gold, the Crash measured 43mm in length and 25mm (23 excluding crown) in width, making it larger than the majority of Cartier models, including most of the subsequent Crash watches. It was powered by the Jaeger-LeCoultre cal. 841, a small tonneau-shaped movement. It is believed that no more than a few dozen examples of the London Crash were made in total.

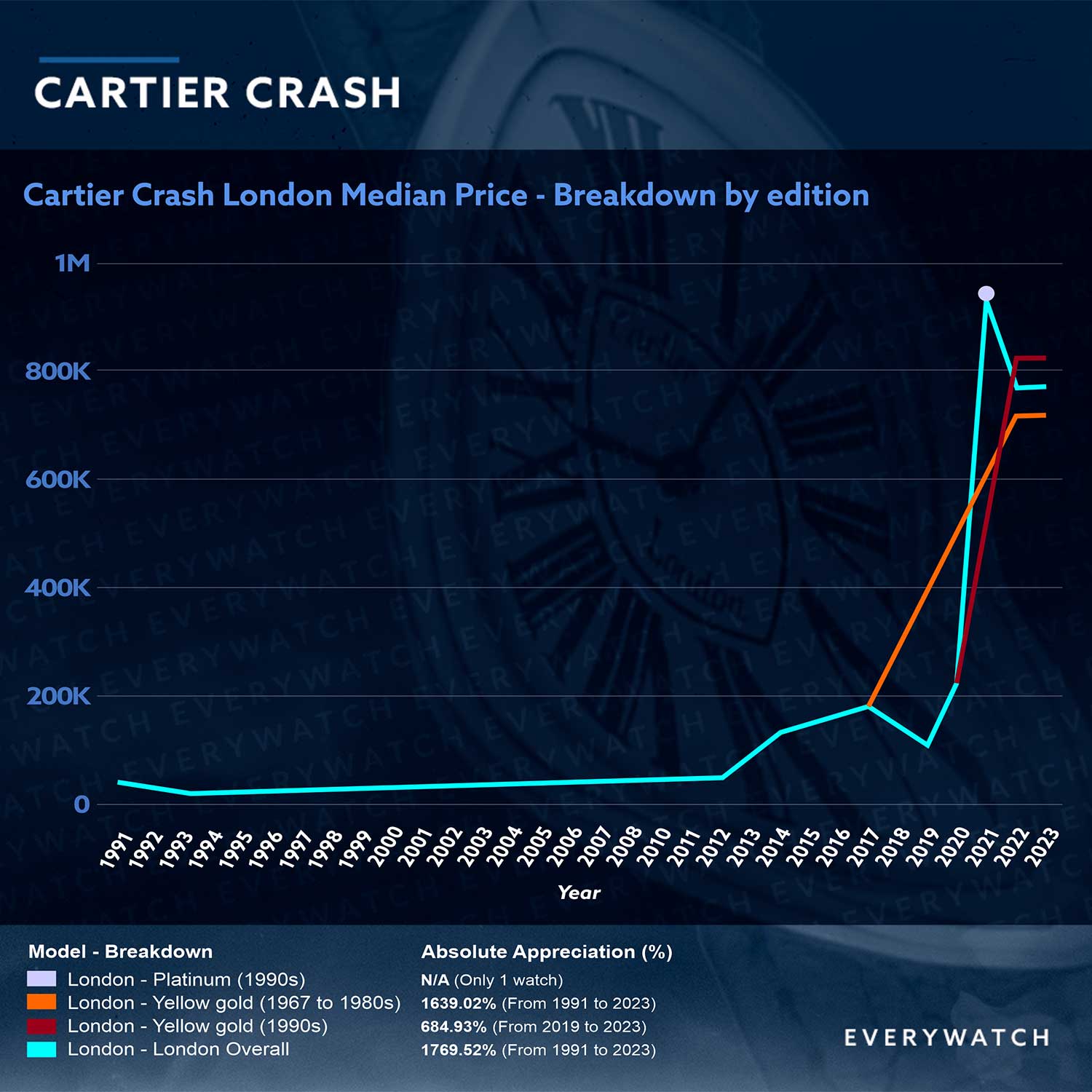

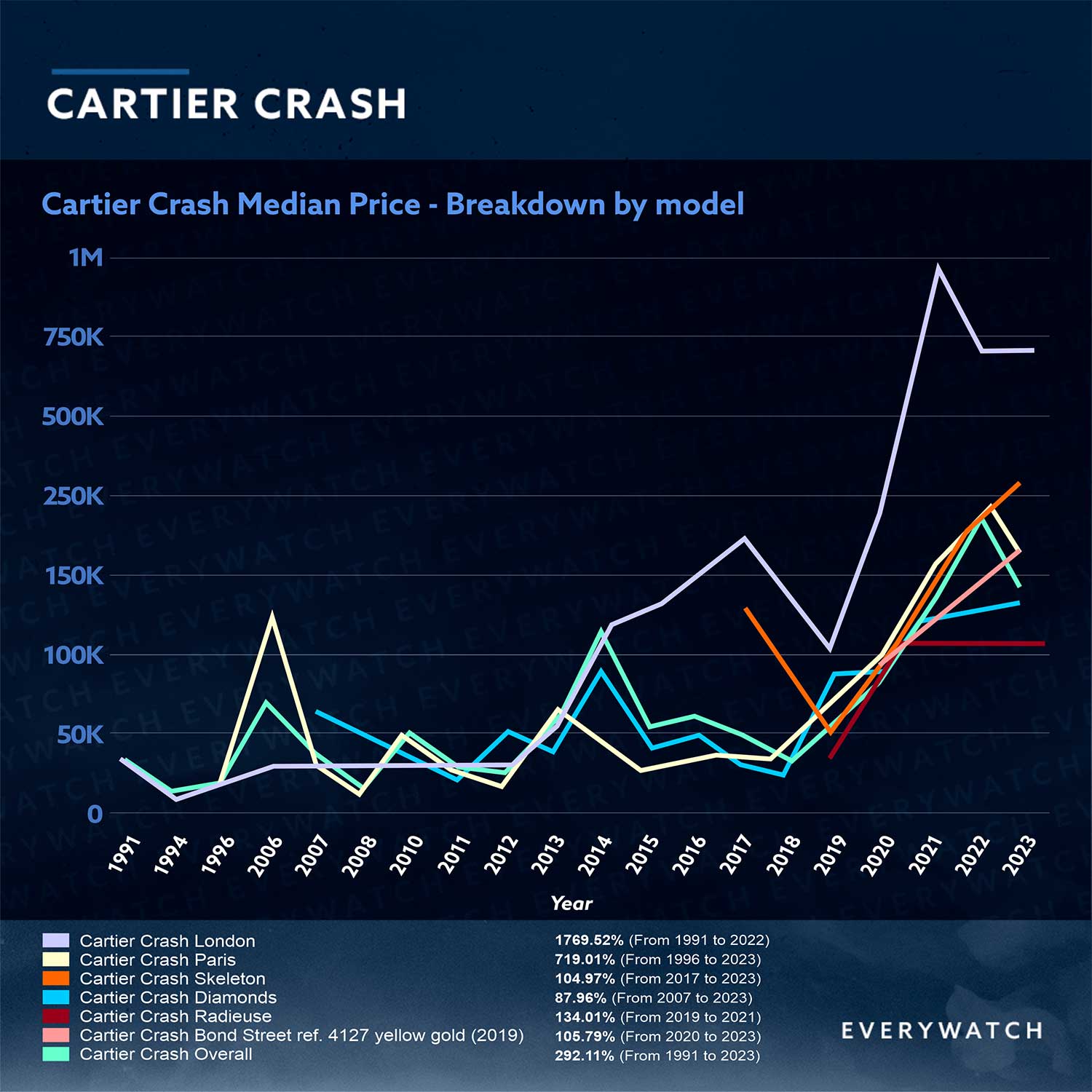

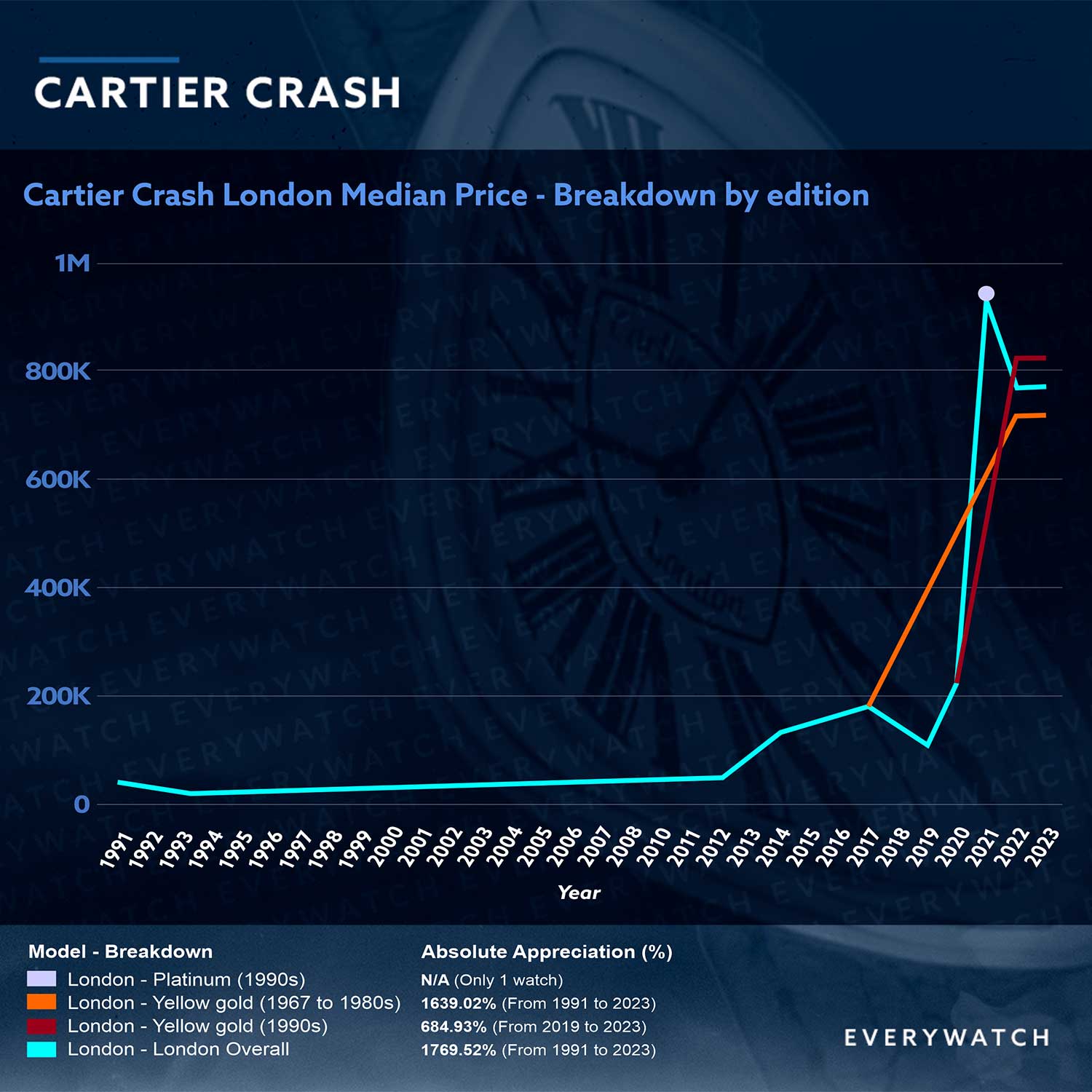

To date, the London Crash has surfaced just 17 times at auction with the highest selling instance being a 1967 example, which sold for a US$1.5 mil on Loupe This in 2022. From 1991 until 2012, it was selling for between US$16,530 to US$41,500, rising slightly in the following years before skyrocketing in 2021. Naturally, the London Crash represents the most valuable Crash watches today. But due to their extreme rarity, sporadic appearances and the high demand from collectors, establishing a stable market value is challenging.

Although the majority of London Crash watches were made in yellow gold, variations exist in other metals as well. A

white gold London Crash appeared at Antiquorum in 1991 while two platinum examples have surfaced at

Christie’s in 2017 and

Pandolfini in 2021 respectively – the 1992 example at Christie’s was later withdrawn while the 1991 specimen sold for a whopping US$974,333. According to Cartier, the first platinum London Crash was produced in 1980. While the production of the Crash was later centralised in Paris, London Crash watches continued to be produced in London until the early 1990s due to pending orders. Notably, examples made from 1990 onwards have a completely different typeface for the “London” script which gave the watch a distinctly bolder character.

A 1991 platinum London Crash netted a a whopping US$974,333 in 2021 (Image: Pandolfini)

A 1991 London Crash in yellow gold featuring a distinct typeface that is characteristic of 90s London Crash watches. (Image: Sotheby's)

Giovanni Prigigallo, co-founder of EveryWatch highlights, “The London Crash, while highly valuable and a top performer today, has a higher unsold rate compared to subsequent models. This phenomenon could potentially be attributed to an initial lack of awareness and appreciation, stemming from the scarcity of information available about them at the time.”

Paris Crash (1991 onwards)

A Crash from the 400-piece 1991 limited edition that had 'Paris' on the dial instead of 'London' and only came in yellow gold. (image: Sotheby's)

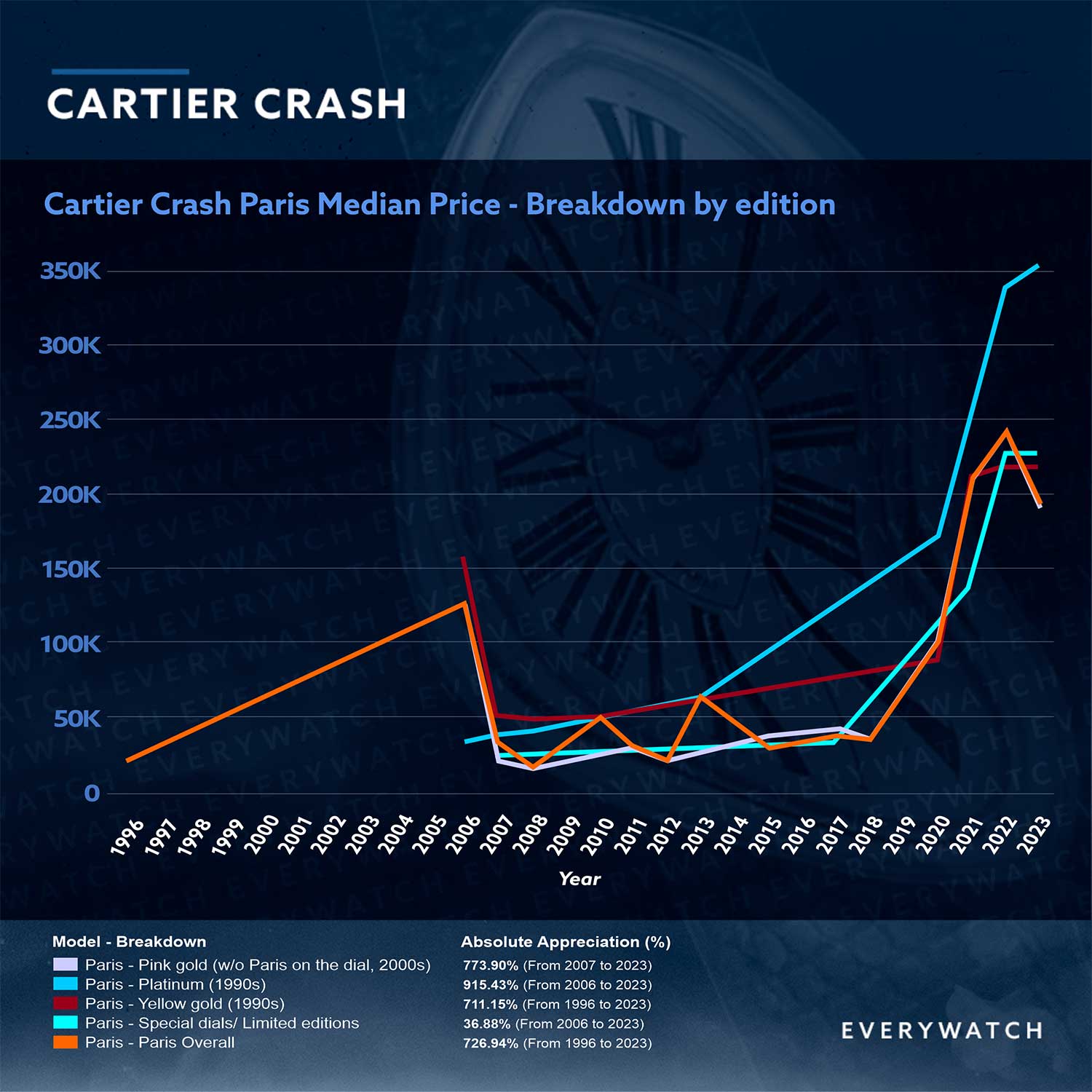

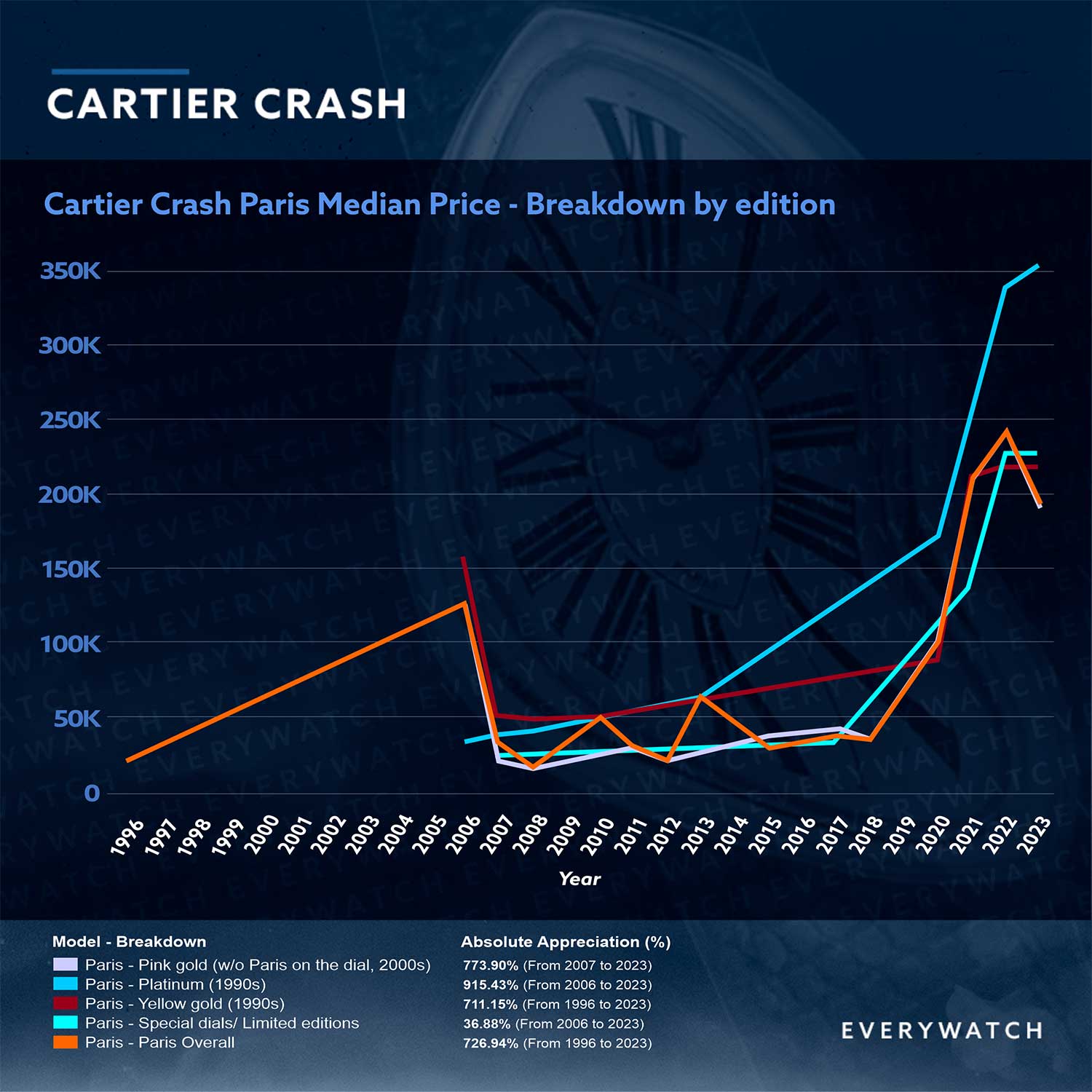

In 1991, Cartier Paris introduced the Crash in a limited edition of 400 pieces in a smaller yellow gold case, measuring 38.5mm by 22.5mm with the word “Paris” at six instead of “London.” Additionally, the Cartier secret signature was incorporated in the numeral VII where the word “Cartier” is written in delicate capital letters.

In the following years, custom orders were produced in various metals including pink gold, white gold and platinum. The next limited edition was released in 1997 when the brand celebrated the re-opening of its flagship store at 13 Rue de la Paix. During the 1990s, Cartier also made market-specific limited editions such as a

40-piece pink gold version with burgundy numerals for the Hong Kong market.

To date, the Paris Crash in yellow gold has emerged 42 times at auction since 1996, making it the most prevalent version. The platinum model in contrast has surfaced only 10 times. Aside from its initial auction debut in 2006, the platinum edition has consistently commanded a higher price than its yellow gold counterpart. Furthermore, this divergence has steadily increased over time, culminating in this year’s sale of a

1992 platinum example at US$353,368 during Phillips’ Geneva Auction XVII in May. The yellow gold in comparison reached its peak at

US$304,700 in May 2022 and last sold for

US$270,869, settling around a median price of roughly US$220,000 as of 2023.

“The Paris Crash in platinum demonstrates impressive growth, comparable to the London version, and is relatively rare, suggesting potential for further market expansion from its latest sale in 2023,” says Prigigallo.

A 1992 platinum example fetched US$353,368 at Phillips Geneva Watch Auction XVII in May (Image: Phillips)

Somewhere between the late 1990s and the new millennium, the word “Paris” was removed from the dial, and in its place, the inscription “made in France” was introduced along the edge. Over the years, a platinum example from 2002 with a

custom burgundy dial has appeared at auction on three separate occasions. It last sold for US$51,141 in 2010. Crash watches bearing the “made in France” marking are predominantly discovered in pink gold, although it was also produced in other colours of gold. The most recent sale garnered

US$224,714 at Sotheby’s in October 2022.

A 2005 example in yellow gold without "Paris" at six. (Image: Cartier)

Crash Diamonds (1990s to present)

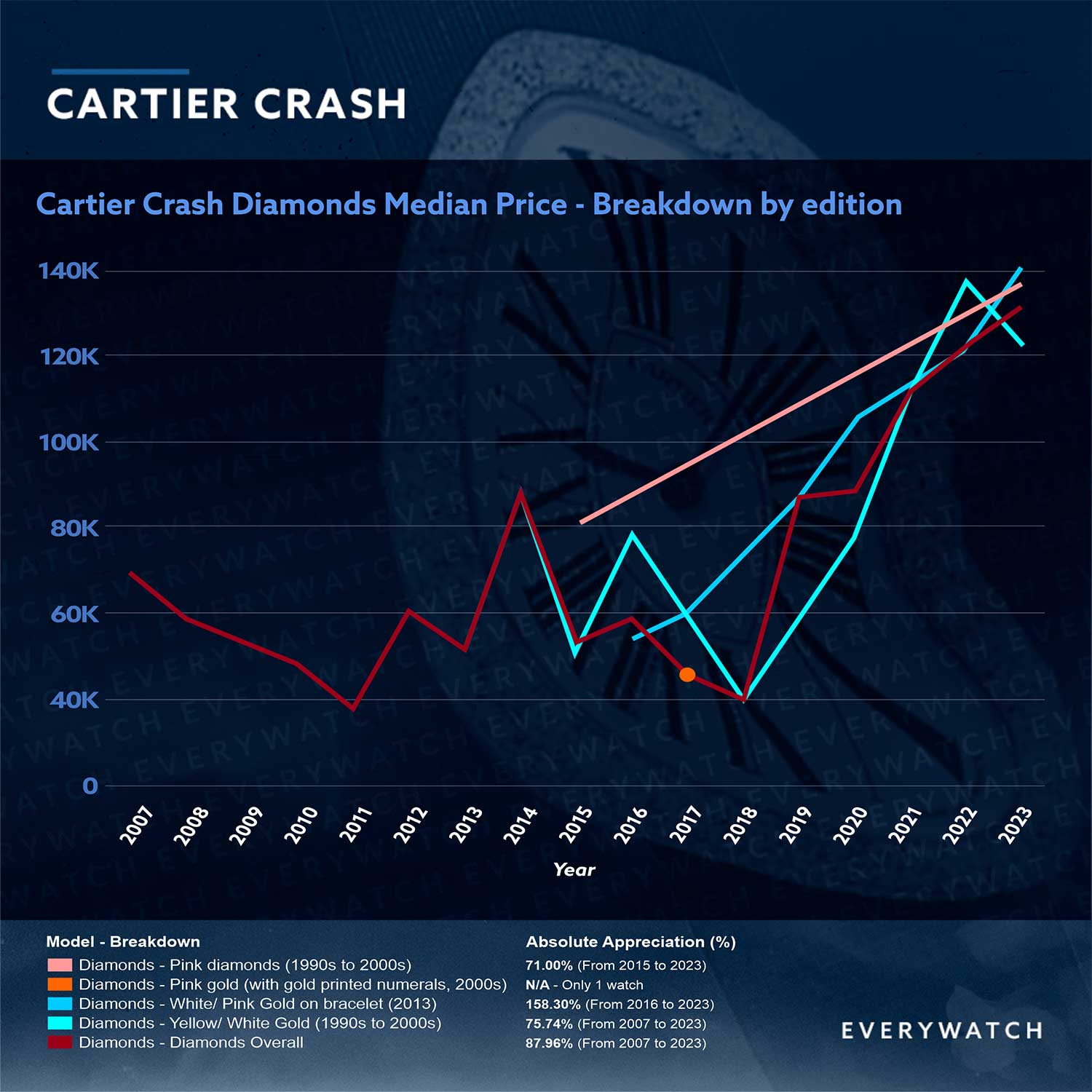

Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, Cartier introduced diamond-set versions in the same 38.5mm by 22.5mm dimensions, beginning with yellow gold. The watch featured three rows of pavé set diamonds and a beaded crown set with a brilliant-cut diamond.

This was later followed by 50-piece white gold limited edition that was launched for yet another re-opening of 13 rue de la Paix in 2005. In between, diamond Crashes were produced as a special order in small quantities in all three colours of gold as well as platinum.

A diamond-set Paris Crash in yellow gold (Image: Cartier)

A diamond-set Paris Crash in white gold that sold for US$105,119 recently at Christie's in November (Image: Christie's)

A pink gold example from 1999 with gold printed numerals (Image: Cartier)

It is worth noting that Cartier presented an alternative interpretation of a distorted Maxi Oval in 2009 with the Baignoire S. It bore a resemblance to the original Crash but had an elongated S shape with numerals that were even more dramatically skewed. Its dimensions were also bolder at 48 mm by 22 mm, providing the stage its design needed.

Another distorted interpretation of the Maxi Oval, the Crash Baignoire S (Image: Monaco Legend Auctions)

In 2013, Cartier unveiled the first Crash on a metal bracelet in both pink and white gold, each limited to 267 pieces. Additionally, there were diamond bracelet variations in both metals, with each of these limited to just 67 pieces.

The limited edition diamond-set Crash with a tear-drop link bracelet launched in 2013 (Image: Cartier)

To date, the diamond-set Crash watches have emerged 52 times at auction. Interestingly, within the realm of diamond-set Crash watches, value is determined more by objective attributes than by their production year, diverging from the valuation dynamics observed across the sans-diamonds versions. While the idea of a gendered watch is increasingly antiquated, the Crash Diamonds, due to its dimensions and presence of diamonds, is quite squarely a ladies’ watch. As such, the trend might suggest that female buyers have a different and arguably more practical set of priorities when it comes to Crash collecting.

Diamond-set white and yellow gold examples from the 1990s to the early 2000s reached a pinnacle of

US$192,635 at Christie’s in May 2022 but it has since experienced a substantial dip, going for

US$105,119 at Christie’s in November, notably falling behind

the 2013 bracelet version, which fetched US$153,928 the same month.

Meanwhile, the absence of platinum examples is noteworthy. Examples featuring pink diamonds are extremely rare, having surfaced only twice at auction –

once at Christie’s in 2015, and

more recently at Sotheby’s in October, fetching a price of US$137,839.

A pink gold specimen set with pink diamonds, circa 2001 (Image: Sotheby's)

Prigigallo asserts, “Today, apart from the metal bracelet version, all diamond Crash watches, including special and colourful editions, exhibit modest performance. Nevertheless, they maintain a lower-than-average unsold rate, indicating a level of appreciation among collectors.”

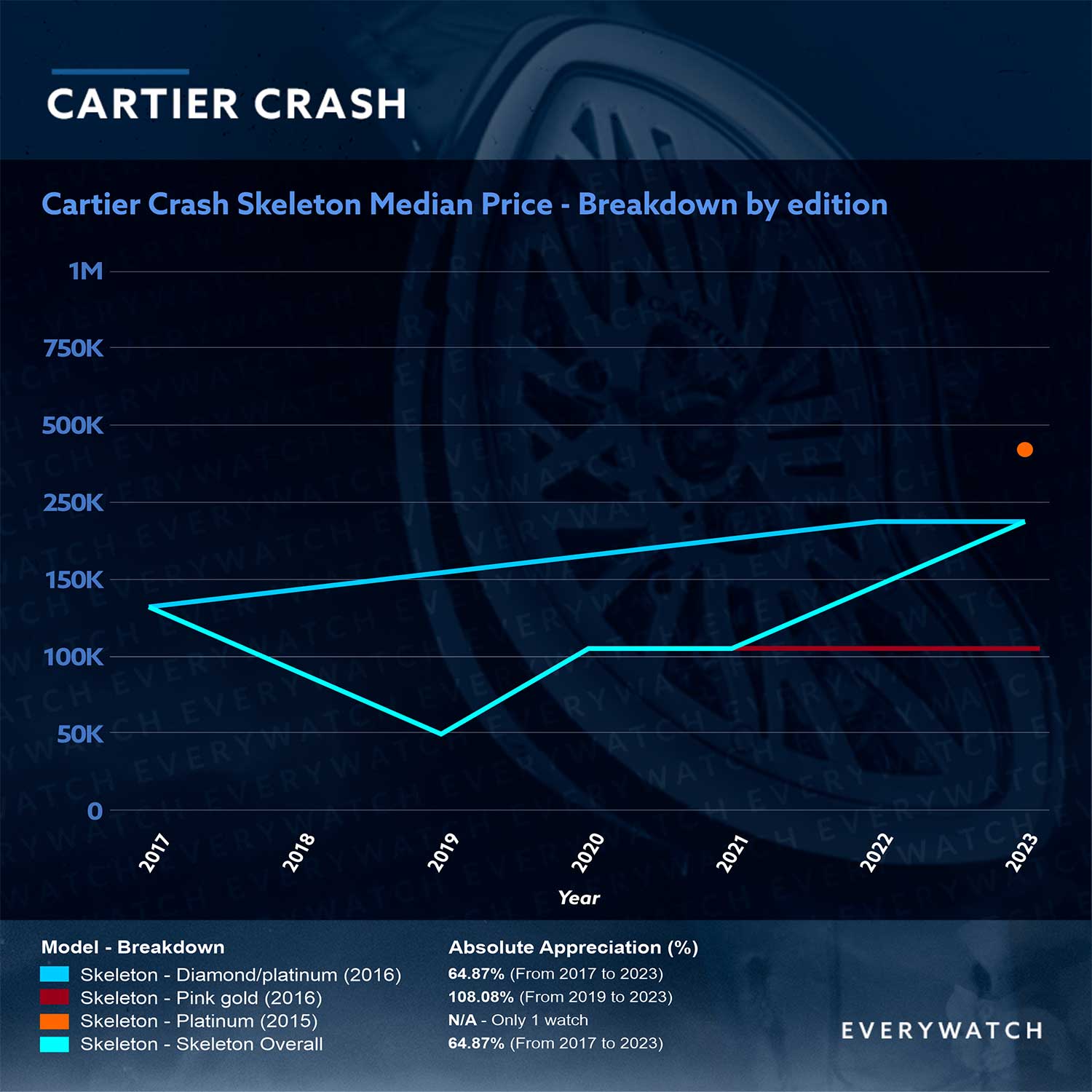

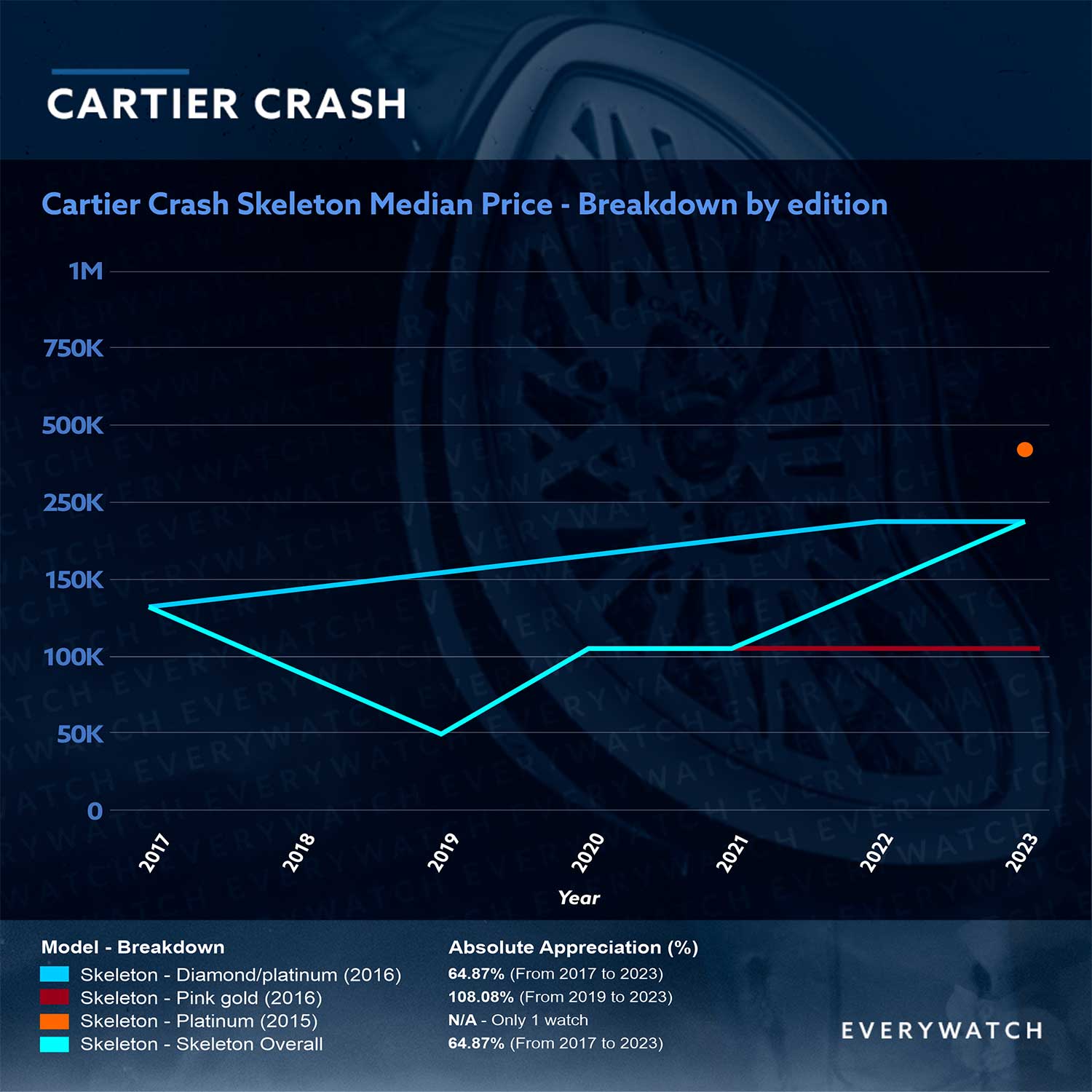

Crash Skeleton (2015 and 2016)

The limited edition Crash Skeleton in platinum launched in 2015, and later in pink gold and platinum adorned with diamonds in 2016

Then in 2015 came the first skeleton model in platinum followed by pink gold and a diamond-encrusted platinum version in 2016, each limited to 67 pieces. The case measured 45.32 mm by 28.15 mm, making it larger than the Crash watches that came before. Most notably, the Crash Skeleton remains the only Crash with a truly shaped movement with its bridges skeletonised to form Roman numerals. The calibre 9618, designed by Carole-Forestier Kasapi, is remarkably impressive. It makes the most of the Crash’s unusual shape by incorporating serially coupled double barrels, along with a vertically aligned gear train that follows the contours of the case, ending with a 4Hz balance wheel at the tip.

To date, only two gold examples have surfaced at auction. It first appeared in 2019, fetching

US$50,000 at Christie’s, before doubling in 2020 to

US$104,041 at Phillips. Similarly, diamond-set platinum examples have made two appearances at auction, fetching

US$136,312 at Christie’s in 2017, before nearly doubling to

US$224,741 in 2022. The platinum version without diamonds made its first appearance this year, fetching a whopping

US$279,400 at Phillips’ New York. In comparison to other Crash models, the Crash Skeleton is the least typical and most mechanically sophisticated variation of the Crash, explaining its high demand despite being modern models.

In 2017, Cartier introduced the Crash Radieuse as part of the Cartier Libre collection. What sets the Radieuse apart was how it played up the Crash’s apocryphal tumultuous origins. In place of distorted numerals, the dial was adorned with black lacquer, forming the striking motif of shockwaves, harmoniously complemented by a grooved case that echoed this design. It was produced in pink gold and was limited to just 50 pieces. The Radieuse made its first appearance at auction in 2019, commanding a price of

US$44,720 at Phillips. Within a brief two-year interval, its value surged, reaching a

staggering US$104,648 when it was sold at Christie’s in 2021. Due to its distinctive case and dial, the absence of diamonds and its large dimensions of 42mm by 23.3mm despite being a part of a jewellery watch collection, it has strong mass appeal and still holds robust potential.

The 50-piece limited edition Crash Radieuse launched in 2017

That year also saw the introduction of two limited edition platinum Skeleton watches – one adorned with blue sapphires and the other, with diamonds and rubies. In the following year, a full ruby version joined the line-up.

The limited edition Crash Skeleton in three striking gem-set iterations: blue sapphires, diamonds and rubies (2017) and one entirely adorned with rubies (2018)

In 2019, to mark the re-opening of the New Bond Street boutique in London, Cartier reissued a yellow gold Crash as well as a white gold diamond-set version, both in slightly larger dimensions than the original London Crash and identical to that of the Crash Skeleton, measuring 45.32mm by 28.15mm. The yellow gold Crash is limited to one piece a month while the diamond-set Crash is limited to 15 pieces. They were followed by a limited production platinum version this year, all of which are exclusive to the New Bond Street boutique.

Two yellow gold specimens have surfaced at auction so far, initially selling for US$96,767 at Phillips Hong Kong in 2020 before more than doubling a year later to US$199,132 at Phillips Geneva. Prigigallo says, “Despite being a newer model, the New Bond Street Crash shows strong performance and potential for growth, making it a promising market opportunity.”

The New Bond Street exclusive in yellow gold (limited production), white gold set with diamonds (limited to 15 pieces and platinum (limited production)

In 2019, Cartier introduced a trio of platinum Skeleton models set with coloured gemstones – yellow diamonds, pink sapphires and a third variant with a combination of diamonds and emeralds.

Limited edition platinum Skeleton models with exuberant gem-setting launched in 2019

Last year, Cartier unveiled the Crash Tigrée, the most extravagant and captivating version of the Crash. Limited to 50 pieces, this version melds the art of gem-setting and enamelling to produce an abstract, Rorschach-esque visual effect that evokes a variety of interpretations such as a tiger, a crocodile, a meandering river, or a psychedelic tribute to the Swinging Sixties, depending on one’s perspective. The Tigrée made its auction debut recently in October,

fetching US$210,813 at Sotheby’s.

Crash Tigrée

The years spanning from 2007 to 2014 since the Crash Diamonds started surfacing at auction shows an intriguing narrative. Until 2014, the Crash Diamond commanded more than a London Crash and until 2019, more than a Paris Crash. For instance, in 2012 a

London Crash sold for US$43,750 while a

white gold diamond Crash fetched a sum of US$72,258 in the same year. This demonstrates that the Crash models were initially assessed based on their material value rather than historical significance.

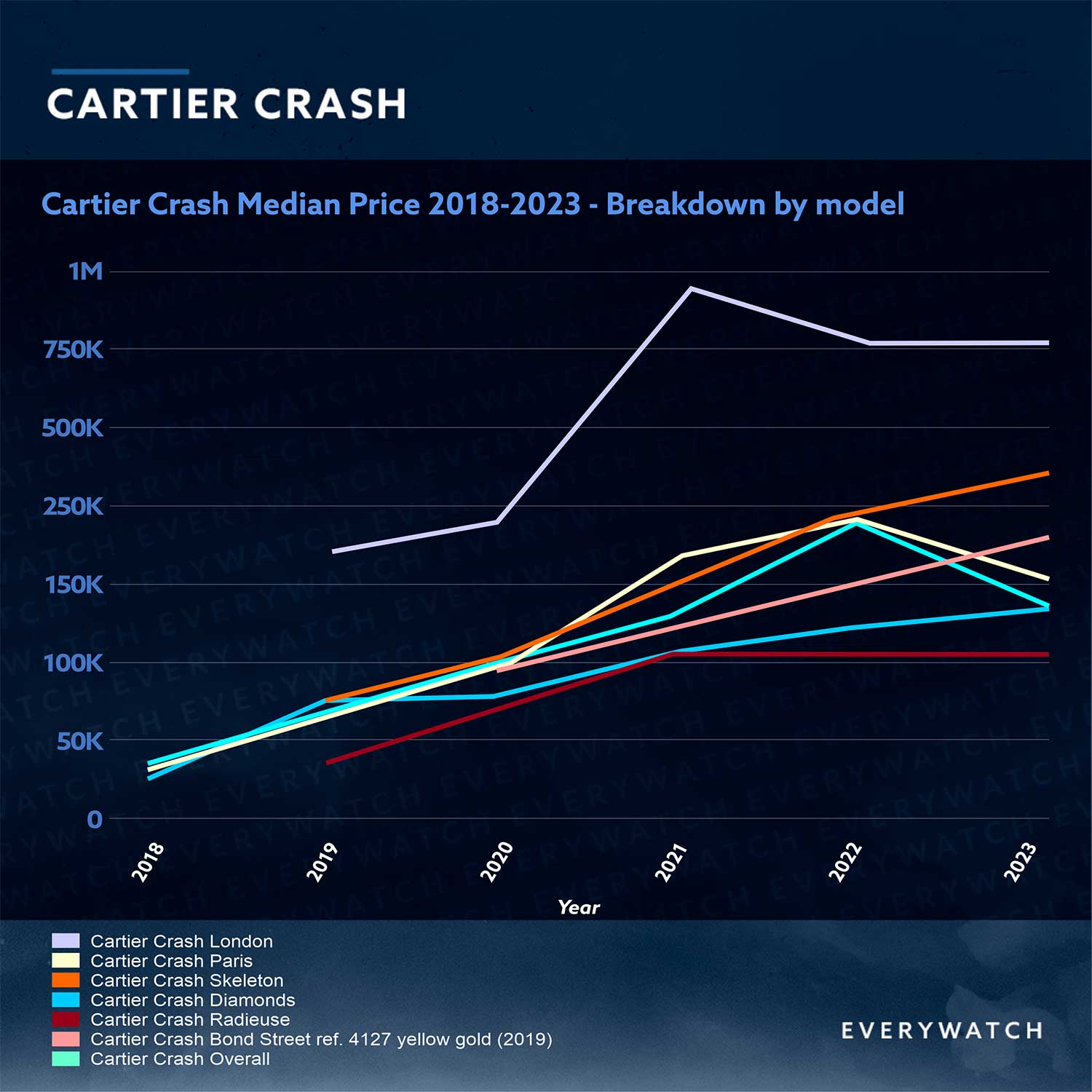

However, a new wind began to blow in 2014, perhaps due to the relaunch of the Crash as a ladies diamond-set watch with bracelet in 2013, which ignited collectors’ interest in the original watch. Additionally, by that time, independent watchmaking had spawned some of the most radical designs to come down the pike, fuelling a broader shift in the perception of creative boundaries. Under that angle, the Crash would have seemed like the perfect middle ground, encompassing both a spirit of rebellion and a classical elegance.

The London Crash achieved a price of US$130,609 at Christie’s in 2014 and subsequently increased to US$175,000 in 2017 when it was sold at Phillips. However, the next time the London Crash emerged in 2019, it saw

a significant dip, dropping to $105,109, which deviated from the upward price trend. This decline can be attributed to factors such as its later, 1990 production year, and the differences in dial graphics that the very last London Crashes entailed.

The London Crash surpassed the US$200,000 mark in the following year before the onset of the pandemic era. As mentioned earlier, a

1991 platinum example achieved a remarkable price of US$974,333 in 2021. Last year, four examples of the London Crash emerged. Among them, the first was

a splendid 1967 specimen that set a record for the Crash, selling for US$1,513,888 on LoupeThis. The second was a

1990 example, which garnered US$825,029 at Christie’s and the third,

a piece from 1989 sold for US$717,363. In contrast, the fourth, a

1970 example, fetched a considerably lower price of US$453,600 despite it being an early example. This was likely due to authenticity concerns raised by

Perezscope prior to the auction.

Over the span of 1996 to 2018, the price set of the Paris Crash witnessed a gradual and incremental rise, inching up from approximately US$24,000 to around US$45,000. Prior to 2015, London and Paris Crash watches were trading at similar price points. However, a noticeable divergence began to manifest in 2014/2015 and the gap only widen with time.

This could be due to the reintroduction of the Crash as a ladies’ watch on bracelet, as mentioned earlier, which sparked greater attention and awareness around the original London production as well as the Paris Crash having more demure dimensions that rendered it a better fit for women. In fact, once the large Crash Skeleton (diamond-set) made its appearance on the market in 2017, it swiftly and significantly outperformed the Paris Crash.

The Paris Crash only started its upward trajectory in 2019, and in 2021 and 2022, it surpassed the US$200,000 mark, outpacing all other Crash models except for the London Crash. The sudden price increase can undoubtedly be attributed to the pandemic while its overtaking of other Crash models is probably a result of the London Crash watches being scarce and increasingly unattainable. Fast forward to 2023, the Crash Skeleton has yet again overtaken the Paris Crash. The platinum Crash Skeleton achieved a price of

US$279,400 at Phillips in June, whereas the median price for the Paris Crash fell slightly to US$192,746. However, for a direct metal-to-metal comparison, a platinum Paris Crash sold for

US$353,368 at Phillips in May. This suggest that the Crash Skeleton is appropriately recognized and valued for its unique mechanical and aesthetic attributes while the Paris Crash has gained broader acceptance and is seen as a compelling alternative to the London Crash despite its smaller dimensions.

Interestingly, the Crash Diamonds in general did not undergo as dramatic a price hike during the pandemic and has stabilized at approximately US$137,000 today. This pricing differential, considerably lower than the London and Paris Crash (sans diamonds), seems to have solidified a new normal, even though it has the exact same dimensions as the Paris Crash and possesses intrinsic higher value. This suggests a heightened awareness regarding the historical significance of the London Crash, with the Paris Crash riding on its coattails albeit still trailing significantly behind, trading at nearly a quarter of London’s present-day valuation. However, to put things into perspective, the present valuation of the Crash Diamonds, while lower than other Crash watches, is similar to that of a 3970 and a 116506 “Platona”.

Summing up, Prigigallo notes, “The Crash London, Crash Paris, and Crash Skeleton models are outstanding performers, while the Diamonds and Radieuse models demonstrate relatively lower performance but their potential for market growth is noteworthy.”

On the whole, the dataset paints a picture of how a watch that started out as a niche curiosity rose to become an institution onto itself. This evolution parallels the growing neutrality and furthermore appreciation towards shaped watches, influenced by the expanding presence of concept- and design-led watchmaking since the 2000s. It also aligns with the broader trend of increased interest in vintage Cartier collecting. The

Cheich, for instance, is a million dollar watch while the

Pebble and

Maxi Oval are trailing not far behind the Crash.

As with many other watches on the auction market, the question of whether it is worth it hangs in the air but the Crash is indeed one of the rare instances of watch design that is deeply rooted in its era yet astonishingly transcendent of it. Demand for it ultimately seems only as robust as its rarity, historical significance, as well as the fact that unlike the usual suspects on the market, there is truly no substitute for it even 56 years on.

The full data report by

EveryWatch will soon be available for download.